The Lips

All operations on the lips should restore both the esthetic appearance of the lips and their function, i.e., their ability to maintain oral continence during eating and drinking. Our suture material of choice for approximating muscle stumps about the lips is 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable, and we prefer 6-0 or 7-0 monofilament for the mucosa.

Mucosal Defects

Wedge-Shaped Defects

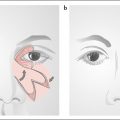

( Fig. 6.1 )

Small scars or defects can be excised ( Fig. 6.1a ) and closed using a Z-plasty technique ( Fig. 6.1b–d ; Dufourmentel et al., after Converse 1977).

Large Superficial Defects

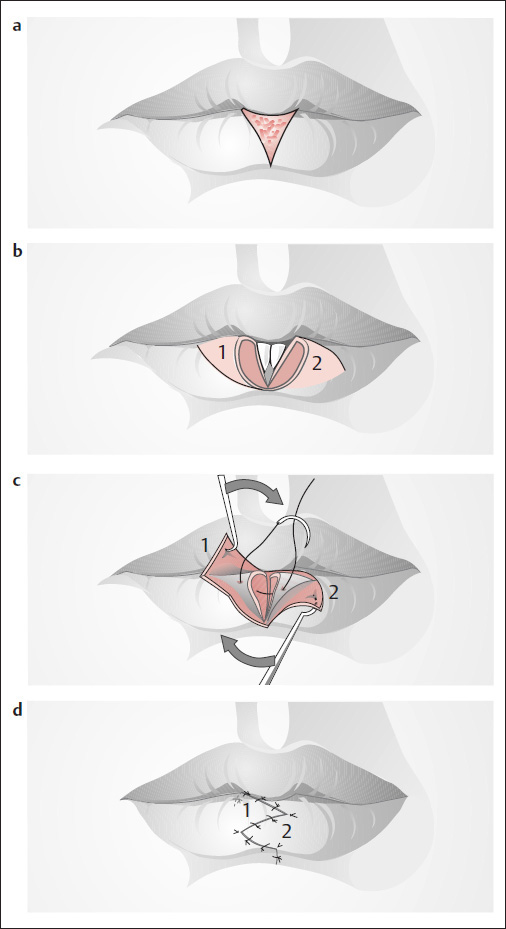

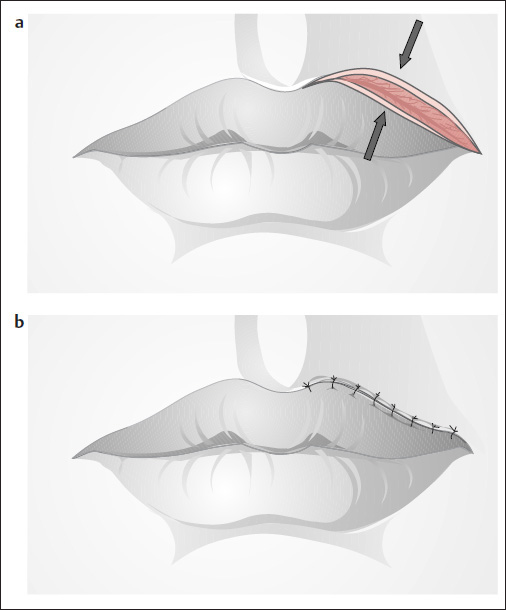

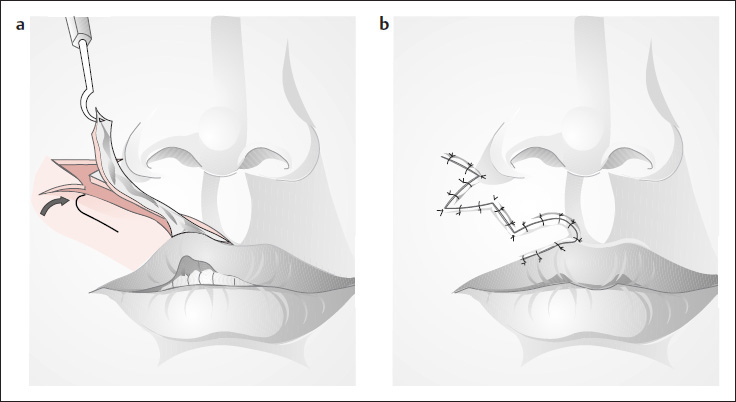

( Fig. 6.2 )

Vermilion defects involving up to one third of the length of the lip can be repaired with a sliding flap ( Fig. 6.2a ), or the entire myomucosal stump can be mobilized as an advancement flap, as described by Goldstein (1990). The natural elasticity of the lip mucosa permits good coverage of the defect ( Fig. 6.2b ; see also Fig. 6.52 ). These techniques can also be combined with the methods described by Blasius (1840) (see Figs. 6.25 and 6.26 ).

Upper Lip

Median Deficiency

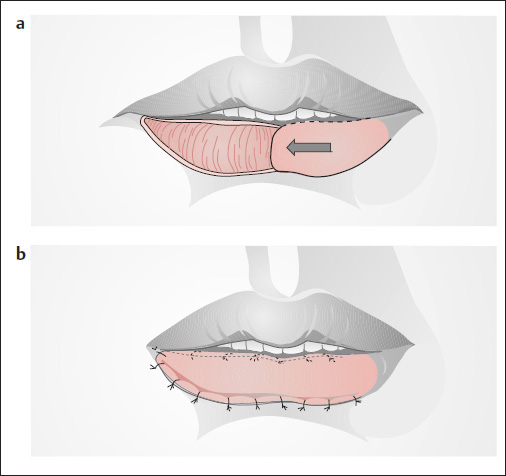

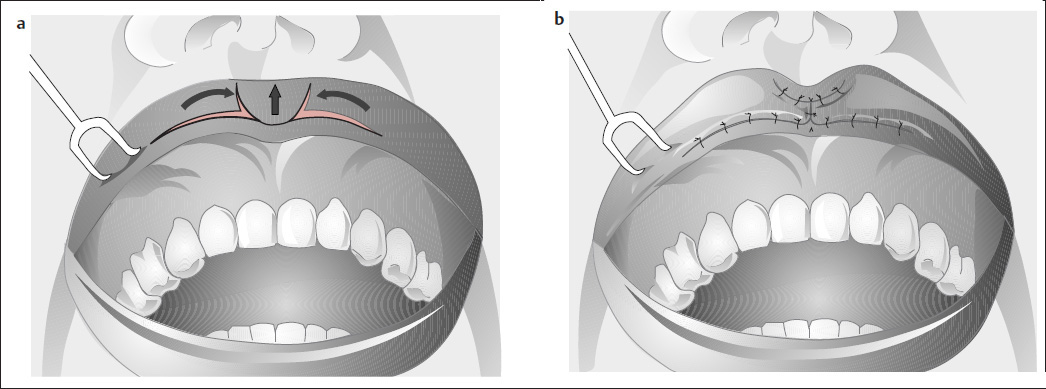

( Fig. 6.3 )

A small median notch or deficiency in the Cupid’s bow of the upper lip can be corrected by advancing the adjacent vermilion toward the midline, using the V-Y method ( Fig. 6.3a, b ).

Thin Upper Lip

Unilateral thinness of the upper lip (or lower lip) can be corrected by measuring the deficit ( Fig. 6.4a ), excising a strip of skin, and advancing the mobilized vermilion ( Fig. 6.4b ). If median deficiency is present, a V-Y advancement from the lateral vestibule ( Fig. 6.5a, b ) can add fullness to the lip. This incision is carried farther laterally than in Fig. 6.3 . We can also use a W-plasty ( Fig. 6.6 ).

Thin Upper Lip and Full Lower Lip

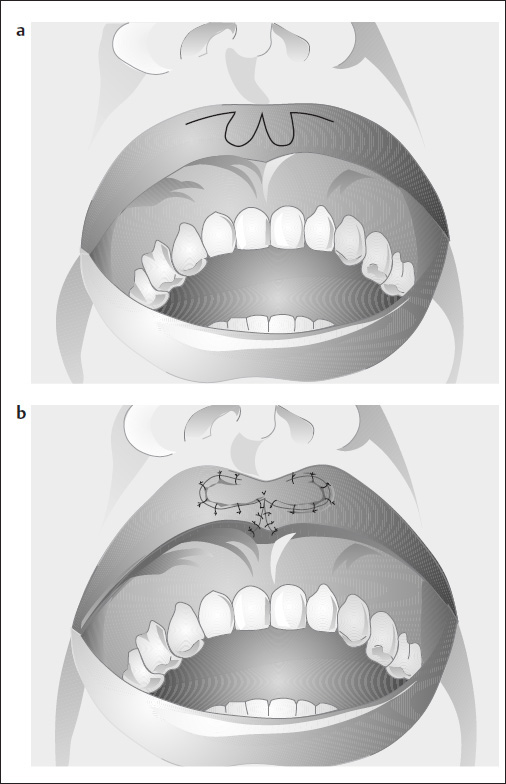

( Fig. 6.7 )

A bipedicle flap can be used to add substance to the upper lip in a patient with a full lower lip, and viceversa ( Fig. 6.7a, b ). The pedicle is divided ~3 weeks after the initial transfer.

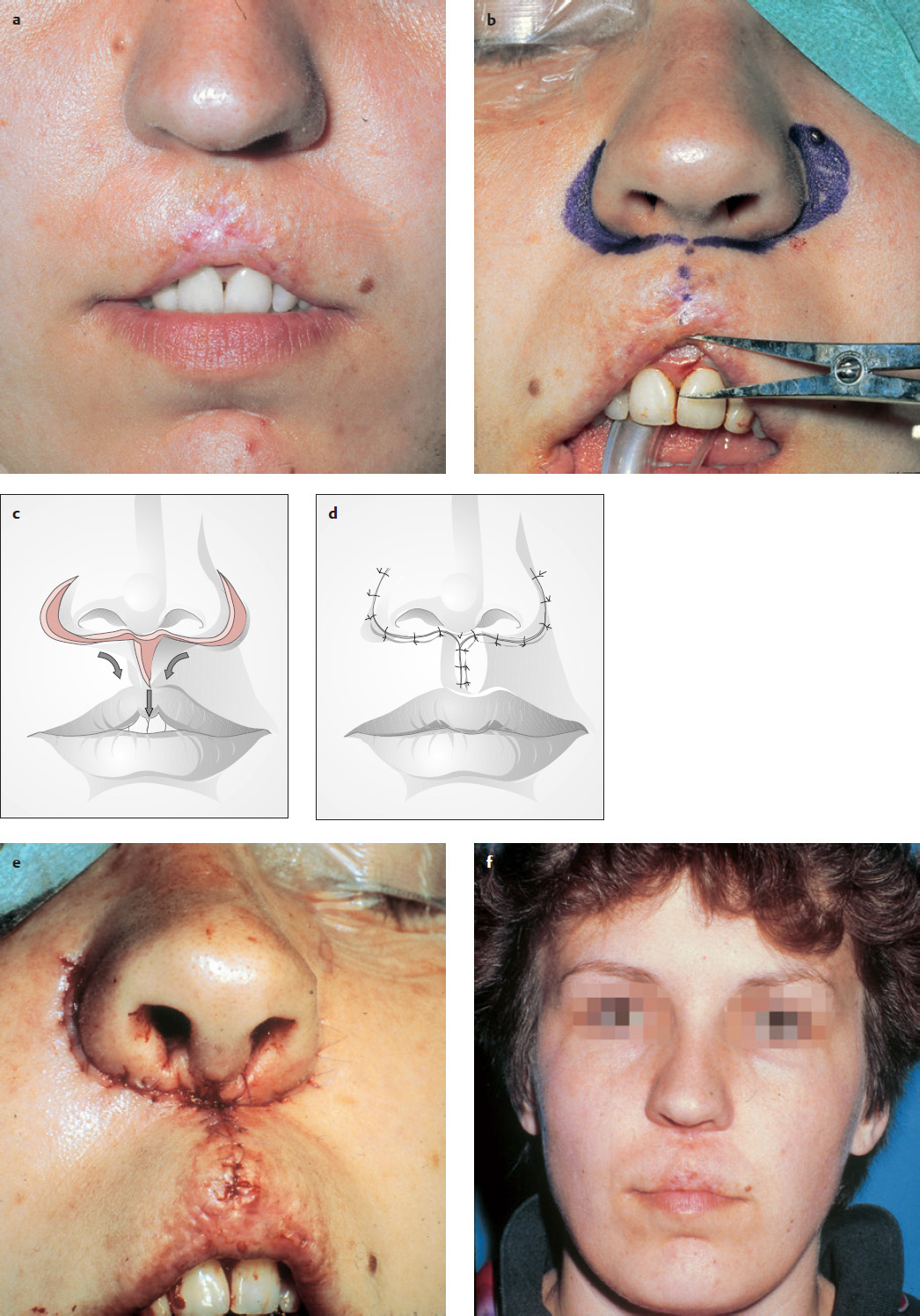

Median Scars and Upper Lip Defects

In cases where the central portion of the upper lip is retracted upward due to scarring after a cleft repair, burn, or irradiation of a hemangioma ( Fig. 6.8a, b ), the lip can be reconstructed using a method first described by Celsus in about 25 AD (Weerda 1994). A two-layer, crescent-shaped excision is made lateral to the alar groove on each side, and extended along the nasal base. A portion of the scar can be excised ( Fig. 6.8b, c ). Both upper lip stumps are then rotated and carefully sutured together to bring down the retracted vermilion ( Fig. 6.8d–f ). The muscle stumps are carefully approximated with 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable suture material.

After the vermilion scar has been divided and excised, a Z-plasty can be incorporated to add fullness to the upper lip and lower the vermilion ( Fig. 6.9 ). With greater upward retraction of the upper lip, the incision along the nasal base and alar groove can be extended at an approximate right angle along the nasolabial fold. The flaps are then rotated toward the midline to restore a natural-appearing upper lip ( Fig. 6.10 ). The lip muscles are reapproximated separately in this type of operation.

Scar Revisions

Small Contractures

( Fig. 6.11 )

In cases where the upper lip has been retracted upward on one side by a small scar, the scar is excised and then dispersed with a Z-plasty. This adds length in the direction of the scar and restores a normal shape to the upper lip. A similar technique is used after excision of small tumors ( Fig. 6.11c, d ; Härle 1993).

Larger Contractures

Burns, caustic injuries, and scar contractures can cause severe distortion of the upper lip. The revision technique is as follows:

The scar is excised down to muscle, and the vermilion is mobilized.

A pattern is made out of paper, cloth, or aluminum foil.

The pattern is used to harvest a full-thickness retroauricular skin graft.

The full-thickness skin graft is inset using fibrin glue and 6-0 or 7-0 sutures. Alternating sutures are left long.

The long sutures are tied over a foam bolster or Vaseline gauze dressing for 6 to 7 days.

Larger Scar Contractures Causing Lip Retraction

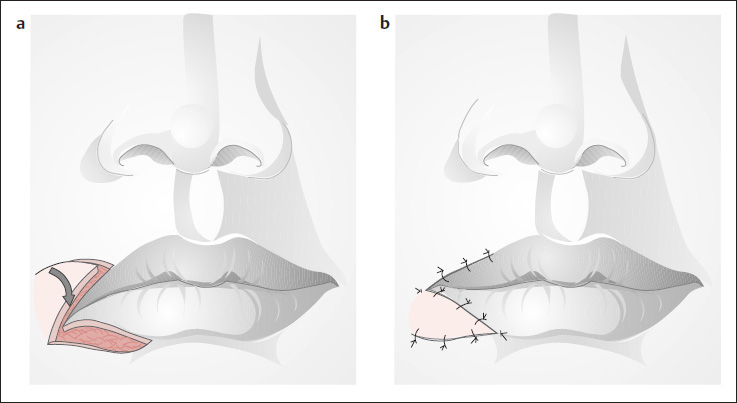

( Figs. 6.12 and 6.13 )

The scar is excised, and the defect adjacent to the vermilion is repaired with a small transposition flap ( Fig. 6.12a, b ).

With contracture and distortion of the oral commissure, the scar is excised ( Fig. 6.13a ) and the angle of the mouth is raised with a Z-plasty ( Fig. 6.13b ).

Defects in the Nasal Floor and Upper Lip

Transposition Flap from the Nasolabial Fold

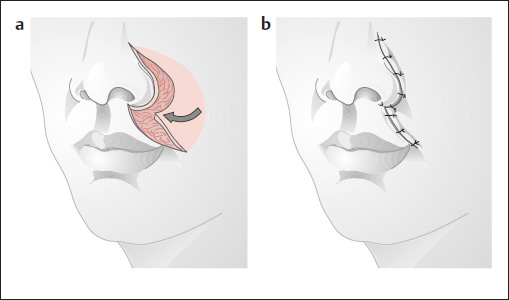

( Fig. 6.14 )

Smaller defects in the nasal floor and upper lip can be covered with a small superiorly based or inferiorly based ( Fig. 6.14a, b ) flap. Large, inferiorly based transposition flaps provide better reach for reconstructing the nasal vestibule and portions of the columella ( Fig. 6.14f ).

Bilobed Flap

( Fig. 6.15 )

Larger defects in this area are repaired with an inferiorly based bilobed flap from the cheek. The first lobe of the flap should cover the nasal floor and upper lip, and the ala should be correctly positioned without tension in the angle between the first and second lobes ( Fig. 6.15a ). A larger defect in the upper lip can be repaired with a full-thickness sliding flap ( Fig. 6.16 ) or advancement flap ( Fig. 6.17e ). In the latter case, a crescent-shaped skin excision is made in the alar groove above the upper lip defect, the cheek skin is mobilized, and the flap is advanced into the defect ( Fig. 6.17a, b ).

For larger defects in the upper lip area, the incision can be extended along the orbital margin and down past the angle of the mouth to create a kind of U-flap ( Fig. 6.18a ) for covering the defect (Weerda and Härle 1981; Weerda and Siegert 1990; Fig. 6.18b ; see also Imre cheek rotation in Fig. 5.25 and Imre–Esser cheek advancement in Figs. 8.2 and 8.4 ).

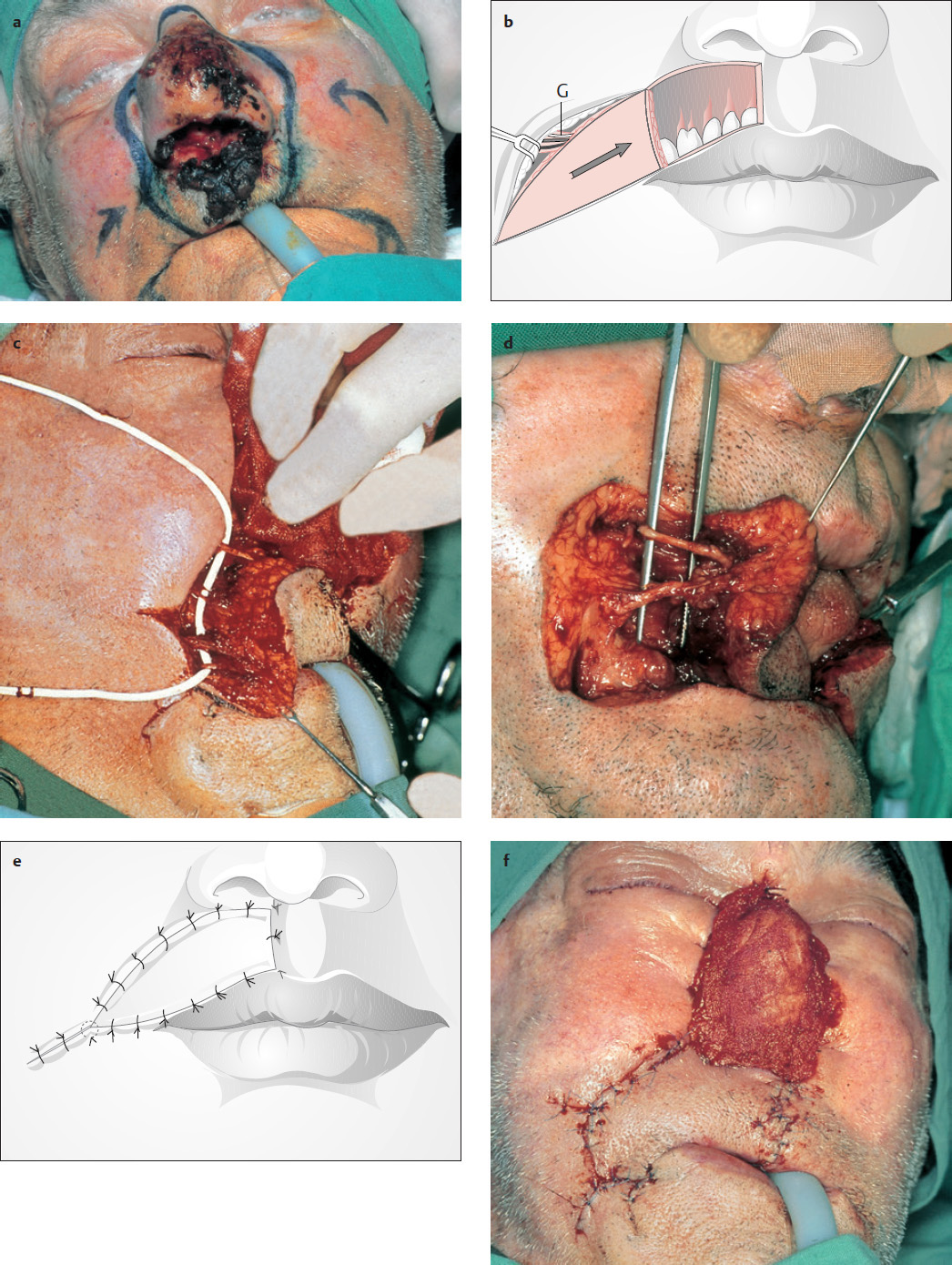

Neurovascular Island Flap from the Lower Cheek (after Weerda 1980d Figs. 6.19 and 6.28)

In this 81-year-old patient, we found a carcinoma of the nose and upper lip ( Fig. 6.19a ). The resulting cheek defects were closed by cheek advancement (see Fig. 5.52a, b ). To close the large defect of the upper lip, a two- or three-layered neurovascular island flap of the cheek is incised ( Fig. 6.19b–d ). The vessels and the branch of the facial nerve were preserved ( Fig. 6.19b–d ). The lip defect could be closed ( Fig. 6.19e, f ). The remaining defect of the nose ( Fig. 6.19g ) was covered with a defect prosthesis ( Figs. 6.19h and 6.28 ).

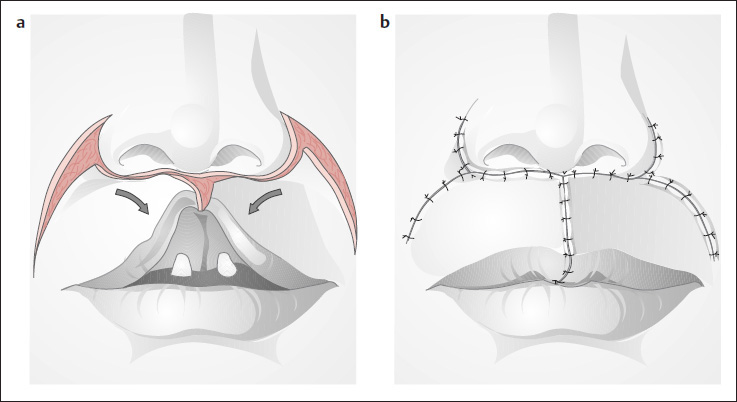

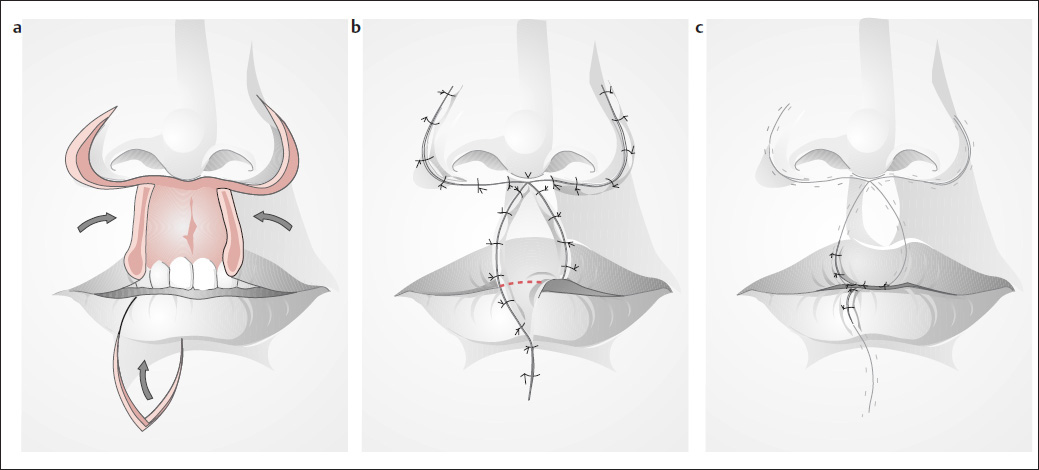

Central Defects of the Upper Lip

As noted earlier (see Figs. 6.18 and 6.19 ), the classic reconstruction described by Celsus (ca. 25 AD) and Bruns (1859) ( Fig. 6.20 ) can also be used to repair full-thickness defects of the upper lip. A perialar skin crescent is excised ( Fig. 6.20a, b ), and the mobilized cheek flap is shifted medially into the defect ( Fig. 6.20c–e ).

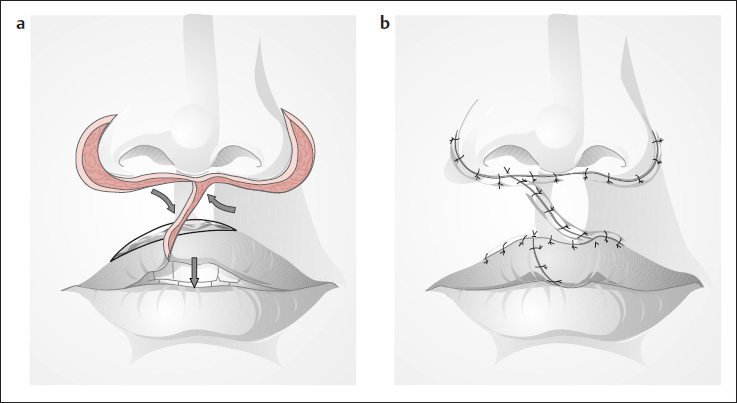

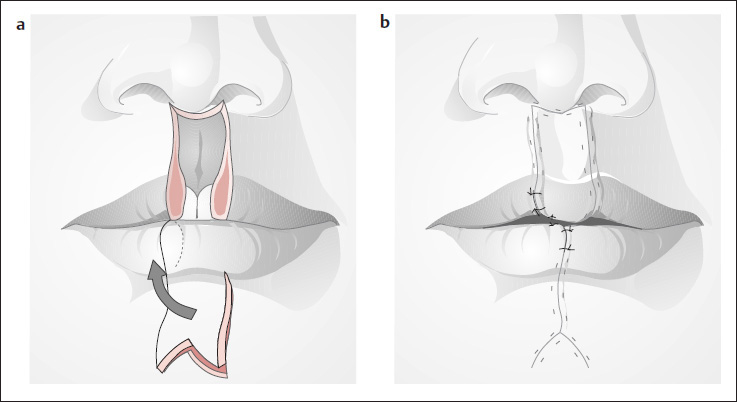

Celsus Method Combined with an Abbé Flap

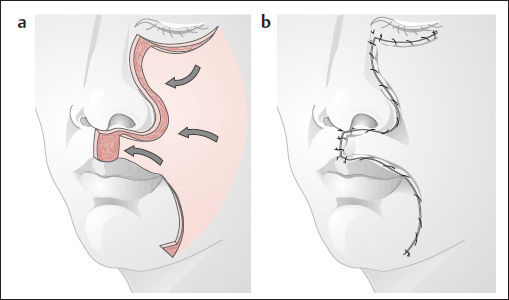

( Fig. 6.21 ; see also Figs. 6.20 and 6.22 )

Large defects of the upper lip can be repaired by closing or reducing the central defect by the Celsus method ( Figs. 6.20 and 6.21a ) and then using a three-layered Abbé flap from the lower lip ( Figs. 6.21b, c and 6.22 ) to replace the central part of the upper lip ( Fig. 6.22a, b ). In a second stage ~3 to 4 weeks later, the turnover flap is detached from the lower lip and the wounds in the upper and lower vermilion are closed ( Fig. 6.21c ).

Classic Reconstructive Techniques in the Upper Lip

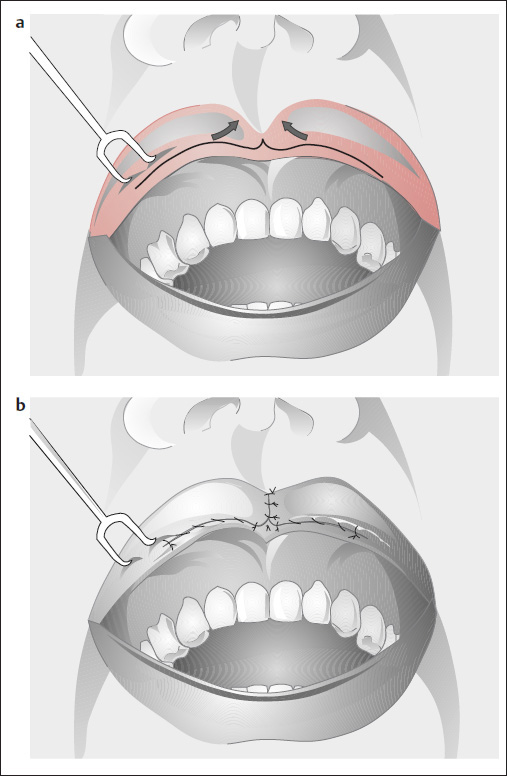

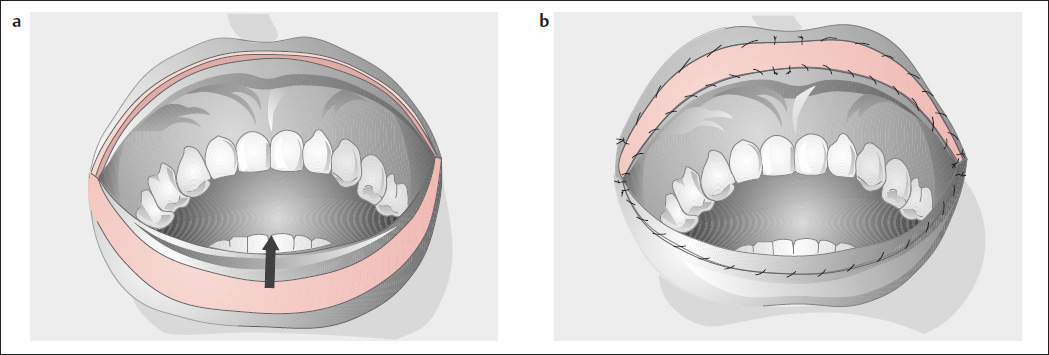

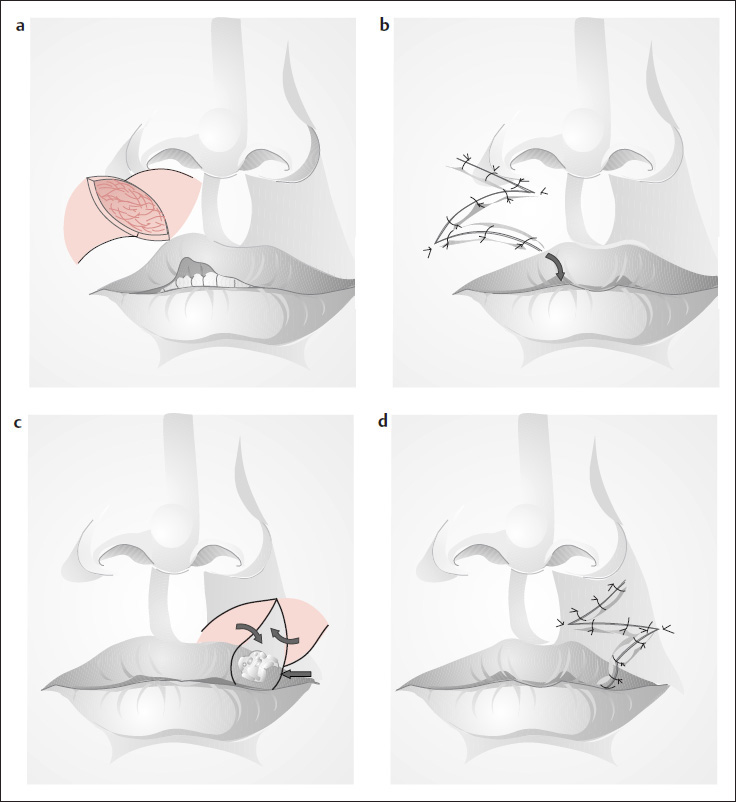

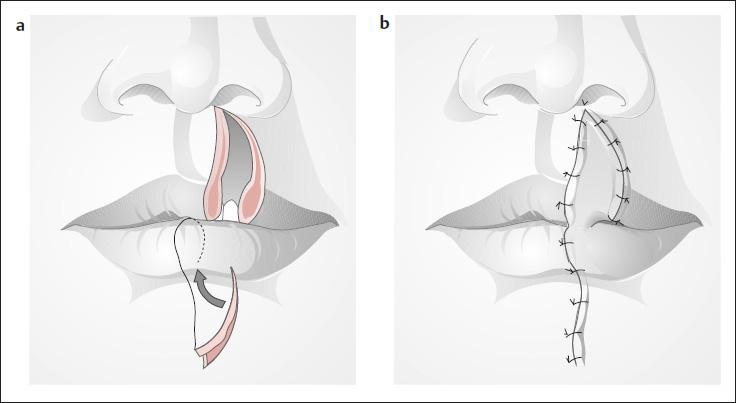

Abbé Flap (1898, reprinted 1968)

( Fig. 6.22 )

Moderate-sized defects of the upper lip can be repaired by transposing a wedge-shaped flap from the lower lip, based on the inferior labial artery. The Abbé “lip switch” is particularly useful for reconstructing defects associated with a cleft lip, or excision of a medially located tumor ( Fig. 6.22a, b ). About 16 to 20 days after the flap has been inset, its vascular pedicle is divided (see Fig. 6.21b, c ). A prong-shaped flap can also be designed ( Fig. 6.23 ; Converse 1977). A Z-plasty can be added to disperse the scar in the lower lip area (see Fig. 6.24d, e ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree