Introduction170

INTRODUCTION

SARCOIDAL GRANULOMAS

SARCOIDOSIS

Histopathology

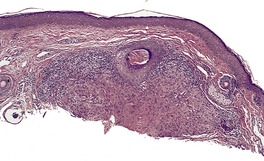

Fig. 7.1

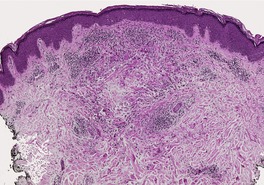

Fig. 7.2

REACTIONS TO FOREIGN MATERIALS

TUBERCULOID GRANULOMAS

TUBERCULOSIS

Histopathology

Histological differential diagnosis

TUBERCULIDS

LEPROSY

Histopathology206

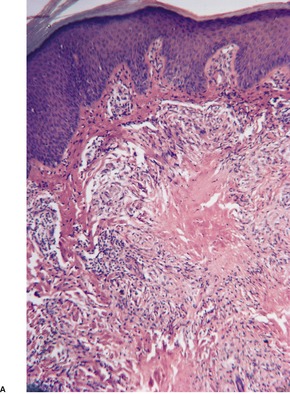

Fig. 7.3

FATAL BACTERIAL GRANULOMA

Histopathology

LATE SYPHILIS

LEISHMANIASIS

ROSACEA

Histopathology225

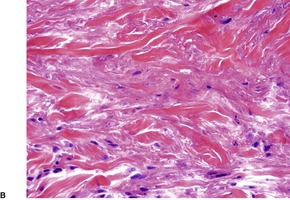

Fig. 7.4

IDIOPATHIC FACIAL ASEPTIC GRANULOMA

Histopathology

PERIORAL DERMATITIS

Histopathology

LUPUS MILIARIS DISSEMINATUS FACIEI

Histopathology

Fig. 7.5

CROHN’S DISEASE

NECROBIOTIC (COLLAGENOLYTIC) GRANULOMAS

GRANULOMA ANNULARE

Treatment of granuloma annulare

Histopathology

Fig. 7.6

Fig. 7.7

Note: additional rare causes of necrobiotic granulomas include injected bovine collagen, Trichophyton rubrum infection, suture material, berylliosis, injection sites of drugs of abuse, hepatitis B vaccine, disodium clodronate, ataxia telangiectasia, parvovirus B19 infection, metastatic Crohn’s disease.

‘Blue’ granulomas

‘Red’ granulomas

Granuloma annulare

Necrobiosis lipoidica

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma

Rheumatoid vasculitis

Rheumatoid nodule

Pseudorheumatoid nodules of adults

Churg–Strauss syndrome

Eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome)

Fig. 7.8

Fig. 7.9

Fig. 7.10

Fig. 7.11

Fig. 7.12

Electron microscopy

NECROBIOSIS LIPOIDICA

Treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica

Histopathology

Fig. 7.13

Fig. 7.14

Fig. 7.15

NECROBIOTIC XANTHOGRANULOMA

Histopathology

Fig. 7.16

RHEUMATOID NODULES

Histopathology

Fig. 7.17

RHEUMATIC FEVER NODULES

Histopathology

REACTIONS TO FOREIGN MATERIALS AND VACCINES

Fig. 7.18

MISCELLANEOUS DISEASES

SUPPURATIVE GRANULOMAS

Fig. 7.19

Histopathology

CHROMOMYCOSIS AND PHAEOHYPHOMYCOSIS

SPOROTRICHOSIS

NON-TUBERCULOUS MYCOBACTERIAL INFECTIONS

BLASTOMYCOSIS

PARACOCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

BLASTOMYCOSIS-LIKE PYODERMA

MYCETOMAS, NOCARDIOSIS, AND ACTINOMYCOSIS

CAT-SCRATCH DISEASE

LYMPHOGRANULOMA VENEREUM

PYODERMA GANGRENOSUM

RUPTURED CYSTS AND FOLLICLES

FOREIGN BODY GRANULOMAS

EXOGENOUS MATERIAL

Fig. 7.20

Fig. 7.21

ENDOGENOUS MATERIAL

XANTHOGRANULOMAS

MISCELLANEOUS GRANULOMAS

CHALAZION

Histopathology

MELKERSSON–ROSENTHAL SYNDROME

Histopathology

Fig. 7.22

ELASTOLYTIC GRANULOMAS

Actinic granuloma

Histopathology

Fig. 7.23

Fig. 7.24

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma

Histopathology

Atypical necrobiosis lipoidica

Histopathology

Granuloma multiforme

Histopathology

ANNULAR GRANULOMATOUS LESIONS IN OCHRONOSIS

Histopathology

GRANULOMAS IN IMMUNODEFICIENCY DISORDERS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The granulomatous reaction pattern

Suppurative granulomas184

Chromomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis185

Sporotrichosis185

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections185

Blastomycosis185

Paracoccidioidomycosis185

Coccidioidomycosis185

Blastomycosis-like pyoderma185

Mycetomas, nocardiosis, and actinomycosis186

Cat-scratch disease186

Lymphogranuloma venereum186

Pyoderma gangrenosum186

Ruptured cysts and follicles186

Xanthogranulomas187

Miscellaneous granulomas187

Combined granulomatous and lichenoid pattern194

The granulomatous reaction pattern is defined as a distinctive inflammatory pattern characterized by the presence of granulomas. Granulomas are relatively discrete collections of histiocytes or epithelioid histiocytes with variable numbers of admixed multinucleate giant cells of varying types and other inflammatory cells. 1 Conditions in which there is a diffuse infiltrate of histiocytes within the dermis, such as lepromatous leprosy, are not included in this reaction pattern. The group is subdivided by way of:

• the arrangement of granulomas;

• the presence of accessory features such as central necrosis, suppuration, or necrobiosis; and

• the presence of foreign material or organisms.

It is difficult to present a completely satisfactory classification of the granulomatous reactions. 2 As Hirsh and Johnson remark in their review of the subject, ‘Sometimes a perfect fit can be achieved only with the help of an enlightened shove’. 3 Many conditions described within this group may show only non-specific changes in the early evolution of the inflammatory process and in a late or resolving stage show fibrosis and non-specific changes without granulomas. Occasionally a variety of granuloma types may be seen in one area, e.g. in reactions to foreign bodies or around ruptured hair follicles.

It is necessary in any granulomatous dermatitis to exclude an infectious cause. In some countries, up to 90% of granulomas have an infectious etiology. 4 Culture of fresh tissue as well as histological search increases the chances of identifying a specific infectious agent. The time-consuming examination of multiple sections may be necessary to exclude such a cause. Special stains for organisms may be indicated. Occasionally fungi are shown only by silver stains, such as Grocott methenamine silver, and not by PAS staining. All granulomas should be examined under polarized light to detect or exclude birefringent foreign material.

Considerable advances have been made in the understanding of the formation and maintenance of granulomas in tissue reactions and the roles played by B and T lymphocytes and cytokines.5.6.7. and 8. It is also clear that there are several types of macrophages in granulomas, particularly at an ultrastructural level. 9 The different forms of multinucleate giant cells seen in granulomas may simply reflect the types of cytokines being produced by the component cells. 10 This new information has not so far been shown to be useful in routine diagnostic problems. The glioma-associated oncogene homologue gli-1 is expressed in lesional skin in patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, granuloma annulare, and necrobiosis lipoidica. 11 These findings provide a rationale for clinical trials of inhibitors of gli-1 signaling, including tacrolimus and sizolimus, for the treatment of these conditions. 11 Polymerase chain reaction techniques (PCR) have proved useful in detecting infectious agents in tissue sections, particularly mycobacterial species.12.13.14.15. and 16.

The following types of granulomas form the basis of the subclassification of diseases in this reaction pattern.

• Sarcoidal – granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells with a paucity of surrounding lymphocytes and plasma cells (‘naked’ granulomas).

• Tuberculoid – granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes, giant cells of Langhans and foreign body type with a more substantial rim of lymphocytes and plasma cells and sometimes showing central ‘caseation’ necrosis. Granulomas have a tendency to confluence.

• Necrobiotic (collagenolytic) – granulomas are usually poorly formed and there are collections, and a more diffuse array, of histiocytes, lymphocytes, and giant cells with associated ‘necrobiosis’ (collagenolysis). The inflammatory component may be admixed with the ‘necrobiosis’ or form a palisade around it.

• Suppurative – granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleate giant cells with central collections of neutrophils. Chronic inflammatory cells are usually present at the periphery of the granulomas.

• Foreign body – granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate (foreign body-type) giant cells, and variable numbers of other inflammatory cells. There is identifiable foreign material, either exogenous or endogenous in origin.

• Xanthogranulomas – granulomas composed of numerous histiocytes with foamy/pale cytoplasm with a variable admixture of other inflammatory cells and some Touton giant cells

• Miscellaneous – a category in which the granulomas may be variable in appearance or do not always fit neatly into one of the above categories.

Many of the conditions exhibiting a granulomatous tissue reaction have been discussed in other chapters; they will be mentioned only briefly.

The various granulomatous diseases will be discussed, in order, according to the classification listed above.

Sarcoidal granulomas are found in sarcoidosis and in certain types of reaction to foreign materials and squames.

The prototypic condition in this group is sarcoidosis. Sarcoidal granulomas are discrete, round to oval, and composed of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleate giant cells which may be of either Langhans or foreign body type. Generally, the type of multinucleate histiocyte present in a granuloma is not helpful in arriving at a specific histological diagnosis. Giant cells may contain asteroid bodies, conchoidal bodies (Schaumann bodies), or crystalline particles. Typical granulomas are surrounded by a sparse rim of lymphocytes and plasma cells, and only occasional lymphocytes are present within them. Consequently, they have been described as having a ‘naked’ appearance. Although the granulomas may be in close proximity to one another, their confluence is not commonly found. With reticulin stains, a network of reticulin fibers is seen surrounding and permeating the histiocytic cluster.

Sarcoidal granulomas can be found in the following circumstances:

• sarcoidosis

• Blau’s syndrome

• foreign body reactions (see Table 7.1)

Silica (including windshield glass)

Silicone

Tattoo pigments

Zirconium

Beryllium

Zinc

Acrylic or nylon fibers

Keratin from ruptured cysts (uncommon)

Exogenous ochronosis

Sea-urchin spines

Cactus

Wheat stubble

Desensitizing injections

Ophthalmic drops (sodium bisulfite)

Sulfonamides

Interferon injection sites

• Sézary syndrome17

• metastatic Crohn’s disease

• orofacial granulomatosis

• granuloma annulare (sarcoidal type)

• herpes-zoster scars18

• breast cancer21

• common variable immunodeficiency (see p. 191)

• X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. 22

Sarcoidal granulomas are exceedingly rare in secondary syphilis (see p. 575), Sézary syndrome, herpes-zoster scars (see p. 617), systemic lymphomas, and breast cancer. The granulomas in metastatic Crohn’s disease and orofacial granulomatosis are often of mixed sarcoidal and tuberculoid types. These diseases are considered with the miscellaneous granulomatous diseases (see p. 188). The sarcoidal variant of granuloma annulare is discussed with other types of this condition (see p. 180). They will not be considered further in this section.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease which may involve any organ of the body but most commonly affects the lungs, lymph nodes (mediastinal and peripheral), skin, liver, spleen, and eyes.23.24.25. and 26. Central nervous system involvement is uncommon. 27 There is an increased incidence of sarcoidosis in people of Irish and Afro-Caribbean origin. 28 Cutaneous sarcoidosis is rare in Asia. 29

Between 10% and 35% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis have cutaneous lesions.30.31. and 32. Although sarcoidosis is usually a multiorgan disease, chronic cutaneous lesions may be the only manifestation. 33 The skin lesions may be specific, showing a granulomatous histology, or non-specific. The most common non-specific skin lesion is erythema nodosum, which is said to occur in 3–25% of cases. 30 Sarcoidosis of the knees is frequently associated with erythema nodosum. 34 An erythema nodosum-like eruption with the histological changes of sarcoidosis has also been described. 35 Sarcoidosis predominantly affects adults; skin lesions are rarely seen in children.36.37.38. and 39. There are reports of its occurrence in monozygotic twins. 40 Children presenting before the age of 4 years, usually have the triad of rash, uveitis, and arthritis,41. and 42. without apparent pulmonary involvement. 42 This early-onset sarcoidosis (OMIM 609464) is caused by mutations in the NOD2/CARD15 gene on chromosome 16q12, similar to Blau’s syndrome (see below). Vasculitis may also occur in this group. 42

A diversity of clinical forms of cutaneous sarcoidosis occurs. These forms include:

• A maculopapular eruption associated with acute lymphadenopathy, uveitis, or pulmonary involvement.

• Plaques with marked telangiectasia (angiolupoid sarcoidosis).

• Nodular subcutaneous sarcoidosis.47.48.49.50.51.52. and 53. This form was diagnosed in 10 of 85 patients (11.8%) in one series. 54 Lesions were most frequently located on the extremities, particularly the forearms where indurated linear bands were sometimes found. It may occur on the breast, mimicking breast carcinoma. 55 Subcutaneous sarcoidosis is the only specific subset of cutaneous sarcoidosis frequently associated with systemic disease. 56

• A miscellaneous group which includes cicatricial alopecia,57. and 58. an acral form, 59 ichthyosiform sarcoidosis,60.61. and 62. ulcerative,63. and 64. necrotizing, morpheaform and mutilating forms,65.66.67.68. and 69. verrucous lesions,70. and 71. discoid lupus erythematosus-like lesions, 72 and erythroderma. 73 Cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas have also been reported at the site of cosmetic filler injections in patients with or without systemic sarcoidosis.74. and 75.

This miscellaneous group represents rare cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis. Lupus pernio may resolve with fibrosis and scarring and is often associated with involvement of the upper respiratory tract and lungs. 76 Oral, eyelid, and scrotal lesions have been reported.77.78. and 79. The majority of skin lesions resolve without scarring. Hypopigmented macules without underlying granulomas have been described, particularly in patients of African descent. 80 Other rare presentations have included leonine facies, 81 faint erythema, 82 palmar erythema, 83 vasculitis, 42 alopecia,84. and 85. and lesions confined to the vulva. 86 Sarcoidosis may follow the use of interferon therapy (IFN-α) for melanoma87 or hepatitis C.88.89.90.91.92.93. and 94. Sometimes the lesions are limited to injection site scars in these patients. 95 It may also occur in patients with hepatitis C unrelated to treatment. 96 It has also followed BCG vaccination. 97

It is generally considered that the presence of cutaneous lesions in association with systemic involvement is an indicator of more severe disease. Skin lesions may occur in scars98.99.100. and 101. following trauma (including surgery, desensitizing injection sites, and venepuncture),102.103. and 104. cosmetic tattoos,105. and 106. radiation, and chronic infection. In some cases these lesions may be the first manifestation of sarcoidosis.107. and 108. Other cases do not appear to be related to systemic sarcoidosis and may be a sarcoidal reaction to a foreign body. 109

Various systemic diseases have been reported in association with cutaneous sarcoidosis. The association in many of these conditions is probably fortuitous. They include B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 110 cutaneous lymphoma,111. and 112. pyoderma gangrenosum, 113 hypoparathyroidism, 114 cryptococcal infection, 115 dermatomyositis, 116 primary biliary cirrhosis, 117 autoimmune thyroiditis and/or vitiligo,118.119. and 120. polycythemia vera, 121 Wegener’s granulomatosis, 122 and HIV infection. 123 In cases of HIV infection, sarcoidosis may develop after the commencement of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and the restoration of some immune function.123. and 124. The term ‘immune restoration disease’ has been used for this circumstance. Subcutaneous granulomas and granulomatous tenosynovitis have been reported in an organ transplant recipient. 125

The etiology of sarcoidosis remains controversial although an infectious origin has long been suspected.126. and 127. The main candidate is a cell-wall-deficient form of an acid-fast bacillus, similar, if not identical to, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. 128 In one study, DNA sequences coding for the mycobacterial 65 kDa antigen were found in 11 of 35 cases of sarcoidosis, 129 while in a more recent study, using only cutaneous specimens, mycobacterial DNA was demonstrated by PCR in 16 of 20 cases. 130 Non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria constitute the largest group of the species identified in this study. 130 Other findings supportive of a mycobacterial etiology are the beneficial effects of long-term tetracyclines131 and the activation of a case following concurrent M. marinum infection of the skin. 132 In a study of 35 patients with sarcoidosis in 2005, M. tuberculosis rRNA was not detected in any case. 133 Based on these results the authors concluded that this organism cannot be considered as the etiological agent of the disease. 133 Another study concluded that there was no role for human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8) in the etiology, despite earlier reports suggesting a role. 134

Several studies have reported increased T-helper (Th)-1 cytokines with increased levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in patients with sarcoidosis. 135

The exact relationship of Blau’s syndrome (OMIM 186580) to sarcoidosis is becoming clearer. It is characterized by the familial presentation of a sarcoid-like granulomatous disease involving the skin, uveal tract and joints, but not the lung. 136 Camptodactyly is another defining sign. 137 Ichthyosis has been reported in one case. 138 Onset is in childhood and the mode of inheritance is autosomal dominant. It shares with early-onset sarcoidosis mutations in the NOD2/CARD15 gene which maps to chromosome 16q12.139.140. and 141. Some patients with Crohn’s disease also have mutations in this gene.

For limited cutaneous sarcoidosis, parenteral therapies have been the mainstay of therapy but systemic therapy has been used for severe cutaneous disease, particularly if there is an aesthetic impact. 142 Therapies that have been used include corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, allopurinol, methotrexate, isotretinoin, mepacrine, 143 tacrolimus, 144 thalidomide, 142 and various inhibitors of TNF-α such as adalimumab145. and 146. and infliximab.135. and 147. The various therapies used to treat cutaneous sarcoidosis have recently been reviewed. 148

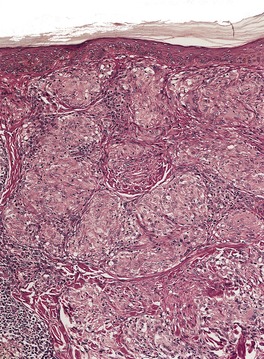

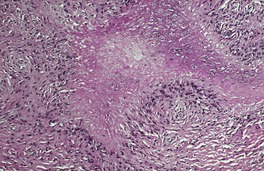

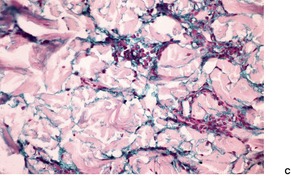

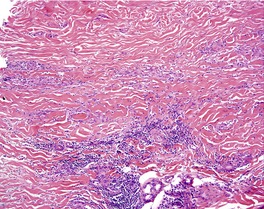

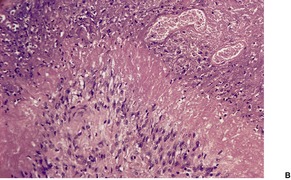

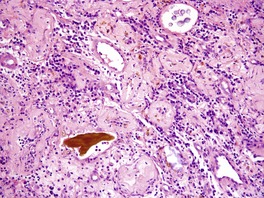

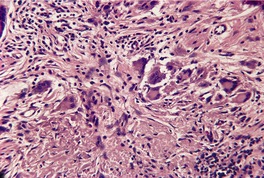

There is a dermal infiltrate of naked sarcoidal granulomas (Fig. 7.1). 149 Granulomas may be present only in the superficial dermis or they may extend through the whole thickness of the dermis or subcutis, depending on the type of cutaneous lesion. 150 Interstitial and tuberculoid granulomas are uncommon. 149 Both perineural and periadnexal localization of the granulomas has been reported.149.151. and 152. A granulomatous vasculitis is exceedingly rare. 153 Necrosis is not usually seen in granulomas but has been reported. 154 Small amounts of fibrinous or granular material may be seen in some granulomas. 23 Increased mucin is present in about 20% of cases. 149 Fibrinoid necrosis is said to be quite common in the cutaneous lesions of black South Africans. 28 Slight perigranulomatous fibrosis may be present but marked dermal scarring is unusual except in lupus pernio or necrotizing and ulcerating lesions. Fibrosis is often present in subcutaneous sarcoidosis. Touton-like giant cells may rarely be present. 155

Sarcoidosis. The granulomas in the dermis are composed of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleate giant cells with only a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes at the periphery (‘naked’ granulomas). (H & E)

In subcutaneous sarcoidosis the granulomas are usually limited to the subcutis without any dermal extension. The infiltrate is predominantly lobular with little or no septal involvement. 54 Discrete foci of necrosis may be present in the center of some granulomas in a few cases. 54 Perigranulomatous fibrosis, sometimes encroaching on the septa, is also present. 156

Overlying epidermal hyperplasia occurs in verrucous lesions70 and hyperkeratosis occurs in the rare ichthyosiform variant. 60 A lichenoid variant has been reported. There was a thick band-like infiltrate of sarcoidal granulomas with basal apoptotic keratinocytes. 157 Otherwise, in most cases, the overlying epidermis is normal or atrophic.

Transepidermal elimination has been reported in sarcoidosis and the histology shows characteristic elimination channels. 158 In some cases the round cell infiltrate surrounding the granulomas is more intense and the granulomas less discrete. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis may then become one of exclusion.

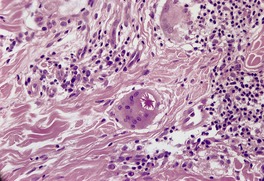

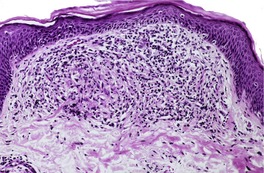

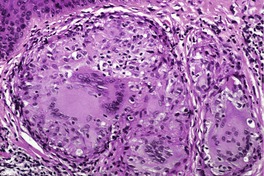

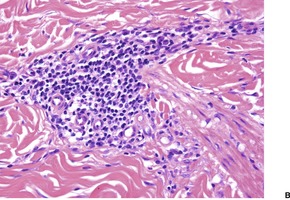

Asteroid bodies and conchoidal bodies (Schaumann bodies) may be seen in multinucleate giant cells but are not specific for sarcoidosis and may occur in other granulomatous reactions including tuberculosis (Fig. 7.2). Schaumann bodies, which are shell-like calcium-impregnated protein complexes, are much more common in the granulomas of sarcoidosis than in those of tuberculosis. 159 Birefringent material has been found in the granulomas from 22–50% of cases.149.150.160. and 161. Foreign bodies are more common in sarcoidal granulomas from sites subject to minor trauma, such as the knee.34. and 161. Furthermore, patients with sarcoidosis can get granulomas at the sites of implantation of foreign material.162. and 163. Electron probe microanalysis has identified calcium, phosphorus, silicon, and aluminum in the birefringent material referred to above. It is thought that the calcium salts are probably the precursors of Schaumann bodies. Another explanation for the material is that it represents foreign material inoculated during a previous episode of inapparent trauma leading to granuloma formation subsequently in a patient with sarcoidosis.164. and 165. Asteroid bodies are said by some to be formed from trapped collagen bundles166 or from components of the cytoskeleton, predominantly vimentin intermediate filaments. 167

Sarcoidosis. An asteroid body is present in the cytoplasm of a multinucleate giant cell. (H & E)

Biopsies taken from Kveim–Siltzbach skin test sites, sometimes used in the past for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, show a variety of changes ranging from poorly formed granulomas with a heavy mononuclear cell infiltrate to small granulomas with few mononuclear cells. Measurement of the serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level has now replaced this skin test.

Immunohistochemical marker studies have shown that the T lymphocytes expressing the suppressor/cytotoxic phenotype (CD8+) are found predominantly in the perigranulomatous mantle whereas those expressing the helper/inducer phenotype (CD4+) are present throughout the granuloma. 168 B lymphocytes are also present in the mantle zone.

Immunofluorescence studies in some cases have shown IgM at the dermoepidermal junction, IgM within blood vessel walls, and IgG within and around the granuloma. A fibrin network is present within granulomas. 169

A number of foreign substances and materials when introduced into the skin may induce a granulomatous dermatitis which histologically resembles sarcoidosis. They are listed in Table 7.1.

Following some kind of trauma, silica may contaminate a wound in the form of dirt, sand, rock, or glass (including windshield glass from motor vehicles). 170 Papules and nodules arise in the area of trauma. The granulomas seen in the dermal reaction contain varying numbers of Langhans or foreign body giant cells, some of which may contain clear colorless particles. These may be difficult to see with routine microscopy but are birefringent in polarized light. The differentiation from true sarcoidosis may be difficult, since granulomas sometimes develop in scars in sarcoidosis and the granulomas can contain birefringent calcite crystals. A sarcoidal reaction to identifiable foreign material does not exclude sarcoidosis. It has been suggested that particulate foreign material may serve as a nidus for granuloma formation in sarcoidosis. 171 Silica-rich birefringent particles have also been described in lesions without a history of injury or silica exposure. 172 Energy-dispersive X-ray analysis techniques using scanning electron microscopy can be used to identify elements present in the crystalline material. 173 The granulomas are thought to develop as a response to colloidal silica particles and not as a result of a hypersensitivity reaction. 174

A granulomatous dermatitis may occur in response to pigments used in tattooing (see p. 389).175. and 176. The skin lesions are sometimes limited to certain areas of a tattoo where a particular pigment has been used. 176 Two patterns are seen, a foreign body type and a sarcoid type. 177 In the latter form there are aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells with a sparse perigranulomatous round cell infiltrate. The histiocytes and giant cells contain pigment particles. True sarcoidosis has also been reported in tattoos, in some cases associated with pulmonary hilar lymphadenopathy. Some of these cases may represent a generalized sarcoid-like reaction to tattoo pigments rather than true sarcoidosis.178. and 179. Other granulomatous complications of tattoos include tuberculosis cutis and leprosy. 180

Sarcoidal granulomas may occur as a rare complication of ear piercing. It is not always a consequence of the trauma/scarring but may represent a contact allergy to nickel and other metals. 181

Zirconium compounds used in under-arm deodorants and other skin preparations have been associated with a granulomatous skin reaction in sensitized individuals.182. and 183. Histologically, the lesions are identical to sarcoidosis. Usually no birefringent material is seen in polarized light. In one case of a reaction to an aluminum–zirconium complex, foreign body granulomas and birefringent particles were seen as well as tuberculoid type granulomas. 184 Ophthalmic drops containing sodium bisulfite have been implicated in the formation of pigmented papules on the face. The papules were caused by sarcoidal granulomas with brown-black pigment in foreign body giant cells. 185

Sarcoidal granulomas have been reported at the injection sites of interferon, both interferon β-1b used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis, 186 and interferon α-2a used in the treatment of hepatitis C. 187

In the past, cutaneous granulomatous lesions with histology similar to sarcoidosis have been reported in persons exposed to beryllium compounds in industry.188. and 189. Other foreign bodies capable of inducing sarcoidal granulomas include acrylic and nylon fibers, wheat stubble, and sea urchin spines.190.191. and 192. Sea urchin spines can produce all types of granuloma, not only sarcoidal ones. The nature of the granulomatous reaction that followed the use of hydroxyurea is uncertain. It may have been sarcoidosis itself. 193

Occasionally, keratin from ruptured cysts or hair follicles can induce sarcoidal granulomas rather than the more usual foreign body type of reaction.

While the granulomas in the tuberculoid group consist of collections of epithelioid histiocytes, including multinucleate forms, they tend to be less circumscribed than those in the sarcoidal group, have a greater tendency to confluence, and are surrounded by a substantial rim of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Langhans giant cells tend to be more characteristic of this group but foreign body type giant cells are also seen. There may be areas of caseation in the lesions of tuberculosis.

Tuberculoid granulomas are seen in the following conditions:

• tuberculosis

• tuberculids

• leprosy

• fatal bacterial granuloma

• late syphilis

• leishmaniasis

• rosacea

• idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma

• perioral dermatitis

• lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei

• Crohn’s disease.

In addition to these diseases, tuberculoid granulomas, some with central necrosis, have been described at injection sites of protamine-insulin, as a hypersensitivity reaction to protamine. One case, consisting of both tuberculoid and sarcoidal granulomas followed Q fever vaccination. 194 The granulomas occurring in the homolateral limb after previous mastectomy, although described as sarcoidal, were more of a tuberculoid nature. 21

Typical tuberculoid granulomas can be seen in the dermal inflammatory reaction of late primary inoculation tuberculosis, late miliary tuberculosis, tuberculosis cutis orificialis, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (‘prosector’s wart’), scrofuloderma, and lupus vulgaris. 195 Cutaneous tuberculosis is discussed in detail with the bacterial infections (see p. 556). A similar pattern of inflammation can be seen after BCG vaccination and immunotherapy.196. and 197.

Santa Cruz and Strayer have stressed the variety of histological changes seen in cutaneous tuberculosis. 198 In many forms, particularly in early lesions, there is a mixture of inflammatory cells within the dermis which includes histiocytes and multinucleate cells without well-formed epithelioid granulomas. The changes seen in the overlying epidermis are variable. In some forms inflammatory changes extend into the subcutis. Areas of caseation may or may not be present within granulomas. In some cases this may be difficult to distinguish from the necrobiosis seen in rheumatoid nodules (see p. 183). The number of acid-fast organisms varies in different lesions. In lesions with caseation, organisms are most frequently found in the centers of necrotic foci. 199 Generally, where there are well-formed granulomas without caseation necrosis, organisms are absent or difficult to find. Neutrophils may be a component of the inflammatory infiltrate, and abscesses form in some clinical subtypes. Both Schaumann bodies and asteroid bodies can occasionally be present in multinucleate giant cells.

In lesions with caseation and demonstrable acid-fast organisms, the histological diagnosis may be straightforward. In lupus vulgaris, however, caseation necrosis, if present, is minimal and organisms are rarely found. Evidence of mycobacterial infection may be determined by polymerase chain reaction techniques. 200

There is usually a heavier round cell infiltrate about tuberculous granulomas than is seen in sarcoidosis. It is to be remembered that the small foci of fibrinous material that sometimes are seen in the granulomas of sarcoidosis may mimic and be mistaken for caseation. Epidermal changes and dermal fibrosis are not commonly part of the histopathology of sarcoidosis.

Lesions of other non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the skin, such as those due to Mycobacterium marinum, may be histologically indistinguishable from cutaneous tuberculosis. Organisms are usually difficult to find in M. marinum infections; they are described as being longer and broader than typical M. tuberculosis. Culture or PCR is required for species identification.

The combination of marked irregular epidermal hyperplasia, epidermal and dermal abscesses, and dermal tuberculoid granulomas may be seen in tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, caused by M. tuberculosis, and in swimming pool granuloma due to M. marinum infection. This reaction pattern is also seen in cutaneous fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, chromomycosis, and blastomycosis. Diagnosis depends on identification of the appropriate organism.

The lesions of tuberculosis cutis orificialis must be distinguished from those of oral or anal Crohn’s disease and from the Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome (see p. 188). This is not always possible on histological grounds and may depend on clinical history and associated lesions. Foci of caseation and acid-fast organisms may be seen in tuberculous lesions. Marked edema and granulomas related to or in the lumen of dilated lymphatic channels are present in the Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome.

The tuberculids are a heterogeneous group of cutaneous disorders associated with tuberculous infections elsewhere in the body or in other parts of the skin (see p. 559). They include lichen scrofulosorum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum-nodular vasculitis. Although it has previously been thought that organisms are not found in tuberculids, recent PCR studies have demonstrated mycobacterial DNA in some cases (see p. 559). 200

In lichen scrofulosorum there is a superficial inflammatory reaction about hair follicles and sweat ducts which may include tuberculoid granulomas. Acid-fast organisms are not usually seen or cultured from the lesions. 201 Caseation is rare. 202

Histopathological studies of papulonecrotic tuberculid have shown a subacute or granulomatous vasculitis and dermal coagulative necrosis with, in some cases, a surrounding palisading histiocytic reaction resembling granuloma annulare. 203 Acid-fast bacilli are not found in the lesions. Tuberculoid granulomas were not described in one study204 but have been recorded in others. 195

In erythema induratum-nodular vasculitis there is a lobular panniculitis, although tuberculoid granulomas usually extend into the deep dermis (see p. 463).

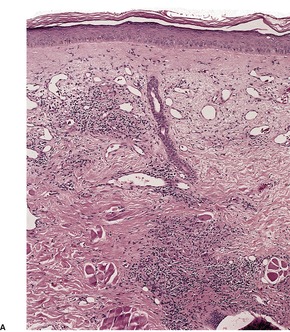

Tuberculoid granulomas are seen in the tuberculoid (TT), borderline tuberculoid (BT), and borderline (BB) groups of the classification of leprosy introduced by Ridley and Jopling. 205 Leprosy is considered further on page 562.

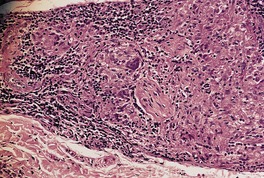

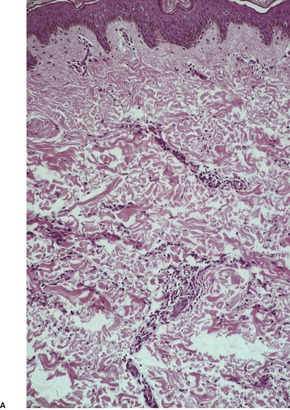

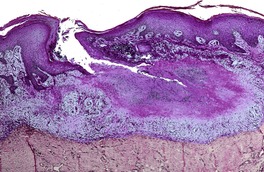

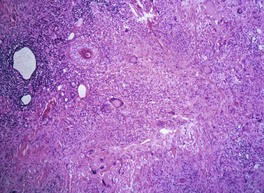

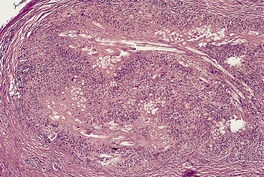

In tuberculoid leprosy (TT), single or grouped epithelioid granulomas with a peripheral rim of lymphocytes are distributed throughout the dermis and subcutis. Unlike lepromatous leprosy this infiltrate does not spare the upper papillary dermis (grenz zone) and it may extend into and destroy the basal layer and part of the stratum malpighii. The granulomas are characteristically arranged in and around neurovascular bundles and arrectores pilorum muscles. Granulomas, particularly in the deeper parts of the infiltrate, tend to be oval and elongated along the course of the nerves and vessels (Fig. 7.3). Small cutaneous nerve bundles are infiltrated and enlarged by the inflammatory cells. There may be destruction of nerves, sometimes with caseation necrosis which may mimic cutaneous tuberculosis. In contrast, the infiltrate in tuberculosis is not particularly related to nerves. The granulomas in tuberculoid leprosy may contain well-formed Langhans-type giant cells and less well-formed multinucleate foreign body giant cells. The causative organism, Mycobacterium leprae, which is best demonstrated by modifications of the Ziehl–Neelsen stain such as the Wade–Fite method, is usually not found in the lesions of tuberculoid leprosy. Rare organisms may be present in nerve fibers. PCR has been used to demonstrate DNA of M. leprae in lesions. 16

Leprosy. The tuberculoid granuloma is elongated along the course of a nerve in the deep dermis. (H & E)

Granulomas in the borderline tuberculoid form (BT) are surrounded by fewer lymphocytes, contain more foreign body giant cells than Langhans cells, and may or may not extend up to the epidermis. Organisms may be found in small numbers or not at all. Nerve bundle enlargement is not so prominent and there is no caseation necrosis or destruction of the epidermis.

In the borderline form (BB) the granulomas are poorly formed and the epithelioid cells separated by edema. Scant lymphocytes are present about the granulomas and there are no giant cells. Nerve involvement is slight. Organisms are found, usually only in small numbers.

This condition was first reported in the English literature in 2002 under the title ‘fatal bacteria granuloma after trauma: a new entity’. 207The cases were reported from rural China. They were characterized by spreading, dark-red plaques that followed slight trauma to the face. The patients had severe headache and clouding of consciousness during the later stages of the disease. All patients died within 1.5– 4 years.

Electron microscopy demonstrated two types of bacteria: one was an anaerobic actinomycete, which was sensitive to lincomycin (a forerunner of clindamycin); the other organism seen was a Staphylococcus. The unknown actinomycete was regarded as the probable causative agent. 207 A recent paper has reported finding Propionibacterium acnes, which seems unusual. 208

The epidermis was normal and there was a heavy, diffuse dermal infiltrate of cells, mainly histiocytes. In addition there were lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and many multinucleated giant cells in some areas. There was vascular occlusion with focal hemorrhage and necrosis in the deep dermis. 207

Some lesions of late secondary syphilis and nodular lesions of tertiary syphilis show a superficial and deep dermal inflammatory reaction in which there are tuberculoid granulomas (see p. 575). 209 Plasma cells are generally but not always prominent in the inflammatory infiltrate and there may be swelling of endothelial cells.210. and 211. One recent study has found that a plasma cell infiltrate and endothelial swelling, traditionally associated with syphilis of the skin, are in fact infrequently seen in biopsies. 212 Organisms are rarely demonstrable in these lesions.

In chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis (see p. 635) and leishmaniasis recidivans, tuberculoid granulomas are present in the upper and lower dermis. 213 The overlying epidermal changes are variable. Occasionally the granulomas extend to the basal layer of the epidermis as in tuberculoid leprosy. 214 Necrosis is not usually seen in the granulomas. 215 Leishmaniae are usually scarce but may be found in histiocytes or, rarely, free in the dermis. The organisms have sometimes been mistaken for Histoplasma capsulatum but differ from the latter in having a kinetoplast.

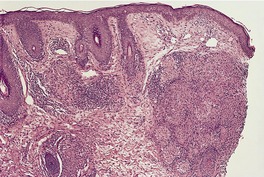

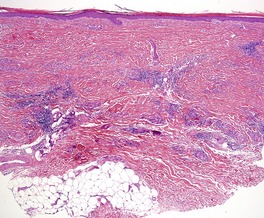

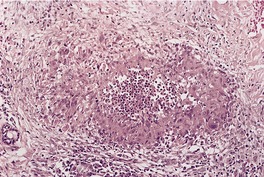

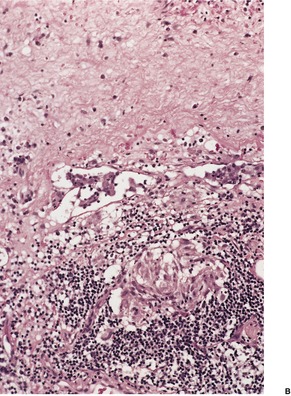

Rosacea is characterized by persistent erythema and telangiectasia, predominantly of the cheeks but also affecting the chin, nose, and forehead (see p. 434). The lacrimal and salivary glands were affected in one case. 216 In the papular form, papules and papulopustules are superimposed on this background. Tuberculoid granulomas are seen in the granulomatous form. Granulomatous rosacea has been reported in children as well as adults, and in association with infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).217.218. and 219. Granulomatous rosacea can be found in most clinical variants of rosacea. 220 A rosacea-like granulomatous eruption developed in an adult patient using tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. 221 Granulomas may be a response to Demodex organisms or lipids.222. and 223. Granulomas have also been described in the lesions of pyoderma faciale, thought to be an extreme form of rosacea. 224

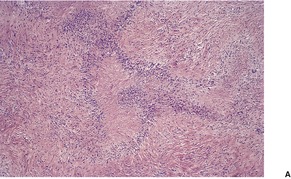

The changes seen in biopsies of the papules are variable and relate to the age of the lesion. Early lesions may show only a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. In older lesions there is a mixed inflammatory infiltrate related to the vessels or to vessels and pilosebaceous units. The infiltrate consists of lymphocytes and histiocytes with variable numbers of plasma cells and multinucleate giant cells of Langhans or foreign body type. In some lesions epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells are organized into tuberculoid granulomas (granulomatous rosacea) (Fig. 7.4). 226 An acute folliculitis with follicular and perifollicular pustules and destruction of the hair follicle is sometimes seen. This corresponds to the perifollicular variant of granulomatous rosacea described by Sánchez et al. 220 Granulomatous inflammation may be centered on identifiable ruptured hair follicles. At other times the granulomas are distributed diffusely through the dermis. 220 There is dermal edema and vascular dilatation. Epidermal changes, if present, are mild and non-specific.

Granulomatous rosacea. Tuberculoid granulomas are present in the dermis. There is some telangiectasia of vessels in the superficial dermis. (H & E)

In granulomatous rosacea, the granulomas are usually of tuberculoid type and not the ‘naked’ granulomas of sarcoidosis (see p. 172). Changes resembling caseous necrosis may be present, associated with a histiocytic reaction. In one series, necrosis was present in 11% of cases. 217 Differentiation from lupus vulgaris may be difficult. In some cases of rosacea the inflammatory changes may be related to damaged hair follicles. The presence of marked vascular dilatation is suggestive of rosacea.

Thirty cases of this unusual granulomatous condition of the face have been reported from a single center in France.227. and 228. All cases occurred in children, with a mean age of 3.8 years. The children presented with one or several acquired painless nodules on the face, lasting for at least one month. There was no response to antibiotics and no infectious agent was demonstrated. It was suggested that the disease might belong to the spectrum of childhood rosacea. 228 A granulomatous response to an embryological residue was also considered. 228

The lesions were composed of granulomas consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, epithelioid cells, some neutrophils, and numerous foreign body giant cells. In one case, the granulomas developed around a non-ruptured epidermoid cyst. 228 Foreign body giant cells would be unusual as the predominant feature in rosacea; accordingly, this etiological theory (see above) seems unlikely.

Perioral dermatitis is regarded by some as a distinct entity229 and by others as a variant of rosacea. 230 The histological changes seen in perioral dermatitis and acne rosacea overlap, and clinical features are often more important in separating these two conditions. 231

Red papules, papulovesicles, or papulopustules on a background of erythema are arranged symmetrically on the chin and nasolabial folds with a characteristic clear zone around the lips. 232 Lesions may occur less commonly on the lower aspect of the cheeks and on the forehead. 233 A periocular variant has also been described.234. and 235. Perioral dermatitis chiefly affects young women, but it has also been reported in children.236.237.238. and 239. In a recent review of patients with lip and perioral area dermatitis, Nedorost has presented a useful table with the distinguishing features between a rosacea-type of perioral dermatitis, a steroid-induced type, and disease due to irritants, allergic/photoallergic contact reactions, and atopic cheilitis. 240 She suggests that an extended patch test series may be useful in making a diagnosis. 240 Inhaled corticosteroids may also induce the disease. 241

Granulomatous perioral dermatitis of childhood is particularly seen in children of Afro-Caribbean descent. This form has been given the acronym FACE – facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption.242.243. and 244. This term is no longer used because of its rare occurrence in non-black children. The term childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis is now preferred.245. and 246. Subtle clinical differences exist between this condition and perioral dermatitis and granulomatous rosacea, although it may still be a variant of one of these conditions. It has also been proposed as a childhood variant of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (see below). 247 It is benign, self-limited, and typically resolves within a year of onset without scarring. 245 Extrafacial lesions may occur.245. and 248. Its resolution seems to be hastened with the use of systemic antibiotics248 or with tacrolimus. 249

In many cases perioral dermatitis appears to be related to the application of one or more cosmetic preparations which may act by occlusion. 250 The use of strong topical corticosteroids, particularly fluorinated ones, may also have an etiological role.251.252. and 253. Various types of toothpaste have been implicated.254. and 255. Perioral dermatitis has been reported in renal transplant recipients maintained on oral corticosteroids and azathioprine. 256 It has also been associated with the wearing of the veil by Arab women. 257

Its relative rarity in patients with seborrheic dermatitis treated with corticosteroids has led to the postulate that perioral dermatitis may develop under fusiform-bacteria-rich conditions, rather than Malassezia-rich conditions as in the case of seborrheic dermatitis. 258

Topical metronidazole, erythromycin, and oral tetracyclines have been used as conventional treatments. Liquid nitrogen, benzoyl peroxide, and oral isotretinoin are other therapies. Recently, topical pimecrolimus has been used successfully. 259 Its efficacy has been confirmed by a randomized, vehicle-controlled study of 1% pimecrolimus cream. It was found to rapidly improve clinical symptoms, being most effective in corticosteroid-induced perioral dermatitis. 260

The histological changes in perioral dermatitis have been described as identical to those seen in rosacea.230. and 236. Others have found the epidermal changes to be more prominent than in rosacea, consisting of parakeratosis, often related to hair follicle ostia, spongiosis, which sometimes involves the hair follicle, and slight acanthosis. 261 The changes in the dermis are similar to those in papular rosacea and consist of perivascular or perifollicular infiltrates of lymphocytes and histiocytes and vascular ectasia. Uncommonly, an acute folliculitis is present. Tuberculoid granulomas have been described in the dermis in some series, but not in others. 261

In childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, epithelioid granulomas are often perifollicular in distribution. This is not a feature of sarcoidosis. 245 Furthermore, the granulomas are more tuberculoid than sarcoidal in type.

Although the cause of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei is unknown, it may be related to rosacea.262. and 263. It has also been called acne agminata and acnitis. 264 It is characterized by yellowish brown papules distributed over the central part of the face, including the eyebrows and eyelids. When widespread facial lesions are present, the appearances may mimic sarcoidosis. 265 Occasionally lesions occur elsewhere, including the axillae.266. and 267. The lesions last for months and heal with scarring. 268 This condition occurs in both sexes, predominantly in adolescents and young adults and rarely in the elderly.269. and 270. It has been suggested that as the currently used name is confusing, a new title should be substituted – FIGURE (facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution). 271

Studies using PCR techniques have failed to demonstrate the DNA of M. tuberculosis in lesional skin. 272

Successful treatment with the 1450 nm diode laser has been reported recently. 273

There are few histopathological studies of this condition. 274 Biopsy appearances overlap those of both rosacea and perioral dermatitis. The characteristic lesion is an area of dermal necrosis, sometimes described as caseation necrosis, surrounded by epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate giant cells and lymphocytes (Fig. 7.5). In many cases granulomas appear related to ruptured pilosebaceous units. 275 Nuclear fragments may be seen in the necrotic foci. Early lesions show superficial perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasional neutrophils. Late lesions have these changes together with dermal fibrosis, particularly about follicles. Established lesions may show tuberculoid or suppurative granulomas. Demodex folliculorum were not seen in one study. 274 Small vessel changes with necrosis of blood vessel walls, thrombi, and extravasated red blood cells have also been described. 266 Acid-fast bacilli are not found in the areas of necrosis and there is no evidence that this condition is related to tuberculosis (see above).

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. A shave biopsy of one of several papules near the lower eyelid. (H & E)

One study of lysozyme in these lesions suggests that there is an immunological mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of this condition rather than a foreign body reaction to an unidentified dermal agent. 276 Conversely, it has been suggested that the lesions represent a granulomatous reaction to damaged pilosebaceous units. 277

Non-caseating granulomas of tuberculoid type may be found, rarely, in the dermis and subcutis in Crohn’s disease (see p. 493). The term metastatic Crohn’s disease is often used for the presence of multiple cutaneous lesions. 278 Granulomas are not uncommon in the wall of perianal sinuses and fistulas. A granulomatous cheilitis has also been reported (see p. 188). 279 It is important to exclude Crohn’s disease in cases of apparent Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome. 280

There is even a report of cutaneous granulomas developing in a patient with histologically proven ulcerative colitis. 281

The term ‘necrobiosis’ has been retained here because of common usage and refers to areas of altered dermal connective tissue in which, by light microscopy, there is blurring and loss of definition of collagen bundles, sometimes separation of fibers, a decrease in connective tissue nuclei, and an alteration in staining by routine histological stains, often with increased basophilia or eosinophilia. The term ‘collagenolytic’ granuloma is favored by others. 282 Granular stringy mucin is sometimes seen in such areas in granuloma annulare, and fibrin may be seen in rheumatoid nodules. Necrobiotic areas are partially or completely surrounded by a histiocytic rim which may include multinucleate giant cells. In some cases histiocytes become more spindle-shaped and form a ‘palisade’.

Necrobiotic (collagenolytic) granulomas283 are found in the following conditions:

• granuloma annulare and its variants

• necrobiosis lipoidica

• necrobiotic xanthogranuloma

• rheumatoid nodules

• rheumatic fever nodules

• reactions to foreign materials and vaccines

• miscellaneous diseases.

Granuloma annulare is a dermatosis, usually self-limited, of unknown etiology and characterized by necrobiotic (collagenolytic) dermal papules that often assume an annular configuration. 284 Either the skin or the subcutis, or both, may be involved. The clinical variants of granuloma annulare include localized, generalized, perforating, 285 and subcutaneous or deep forms.286. and 287. Rare types include a follicular pustulous variant, 288 an acute-onset, painful acral form, 289 and a patch form, 290 although the latter cases are probably examples of the interstitial granulomatous form of drug reaction (see p. 192). The linear variant reported some years ago would now be regarded as a variant of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (see p. 191). 291 Classic granuloma annulare was preceded in one case by the development of a severe linear form along Blaschko’s lines. 292

In the localized form, one or more erythematous or skin-colored papules are found. Grouped papules tend to form annular or arciform plaques. The hands, feet, arms, and legs are the sites of predilection in some 80% of cases. 293 A papular umbilicated form has been described in children in which grouped umbilicated flesh-colored papules are limited to the dorsum of the hands and fingers. 294 The generalized form accounts for approximately 15% of cases.284. and 295. Multiple macules, papules, or nodules are distributed over the trunk and limbs. 296 Rarely, there may be confluent erythematous patches or plaques.297. and 298. The appearances may even simulate mycosis fungoides. 299 It has been reported as a side effect of allopurinol300 and of amlodipine. 301 Lesions in perforating granuloma annulare are grouped papules, some of which have a central umbilication with scale. 302 The extremities are the most common site. The generalized form may also have perforating lesions. 303 A high incidence of perforating granuloma annulare has been reported in Hawaii. 304 It is rare in infants and young children. 305 In subcutaneous (or deep) granuloma annulare, deep dermal or subcutaneous nodules are found on the lower legs, hands, head, and buttocks.306. and 307. These lesions are associated with superficial papules in 25% of cases. 308 This group also includes those lesions described as pseudorheumatoid nodules, palisading subcutaneous granuloma, and benign rheumatoid nodules.309.310. and 311. Although arthritis does not usually occur in children with these nodular lesions, IgM rheumatoid factor has been found in serum in some cases.312. and 313. There is a report of one case occurring in association with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. 311 Computed tomography (CT) scan changes of this variant have been described. 314 Rarely, the changes may involve deeper soft tissues and produce a destructive arthritis and limb deformity. 315 Pseudorheumatoid nodules have also been reported in adults. A recent series of 14 cases all involved females and most involved the small joints of the hand. 316 Granuloma annulare was present at the periphery of the nodules in eight cases. 316 The authors suggested the term juxta-articular nodular granuloma annulare for these cases. 316

Granuloma annulare has been reported as a seasonal eruption on the elbows or hands317. and 318. and from unusual sites such as the penis,319.320.321. and 322. palms, 323 about the eyes,324.325.326. and 327. and ear.328. and 329. There has been one case of cutaneous granuloma annulare associated with histologically similar intra-abdominal visceral lesions in a male with insulin-dependent diabetes. 330

Females are affected more than twice as commonly as males. The localized and deep forms are more common in children and young adults.307. and 331. The deep (subcutaneous) form has been reported as a congenital lesion. 332 Generalized granuloma annulare occurs most frequently in middle-aged to elderly adults. Most cases of granuloma annulare are sporadic but familial cases have occasionally been reported. 333 Patients with the generalized form of the disease show a significantly higher frequency of HLA-BW35 compared with controls and with those who have the localized form of the disease. 334

Lesions of granuloma annulare have a tendency to regress spontaneously; however, about 40% of cases recur. 293 Resolution of lesions subject to biopsy, but not other lesions has been reported. 335 Spontaneous regression of localized lesions in children occurred, in one series, from 6 months to 7 years, with a mean of 2.5 years. 336 In the generalized form, the clinical course is chronic with infrequent spontaneous resolution and poor response to therapy. 296 Non-perforating lesions are usually asymptomatic. 337

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of the skin lesions in granuloma annulare remain uncertain, possible triggering events include insect bites, trauma, the presence of viral warts, drugs, erythema multiforme, and exposure to sunlight.301.338.339. and 340. Lesions have occurred in the scars of herpes zoster, localized or generalized,341.342.343.344.345. and 346. in a saphenectomy scar, 347 in a Becker’s nevus, 348 and at the sites of tuberculin skin tests. 349 The possible link between both the localized and generalized forms and diabetes mellitus remains controversial. There is more convincing evidence of this association with the generalized form than with the localized form although there may be a weak association with nodular as opposed to the annular type of localized lesion.350.351. and 352. Significantly lower serum insulin levels have been found in children with multiple lesions of granuloma annulare. 353 A case-control study failed to find any association between granuloma annulare and type 2 diabetes mellitus. 354 Reported cases of the concurrence of these two diseases may represent the chance association of two not uncommon conditions. 355 It has been reported in association with sarcoidosis, 356 Alagille syndrome, 357 toxic adenoma of the thyroid, 358 autoimmune thyroiditis,359. and 360. uveitis, 361 hepatitis B362 and C infection, 363 parvovirus B19 infection, 364 BCG, 365 hepatitis B, 366 and antitetanus vaccination,367. and 368. waxing-induced pseudofolliculitis, 369 tuberculosis,370. and 371. tattoos, 372 granulomatous mycosis fungoides, 373 a monoclonal gammopathy, 374 hypercalcemia, 375 myelodysplastic syndrome, 376 chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, 377 Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, 378 and metastatic adenocarcinoma.379.380.381.382.383.384.385.386.387. and 388. In these conditions, the clinical presentation may be atypical. 389 Localized, generalized, and perforating forms of granuloma annulare have been reported in patients with AIDS; the generalized form is the most common clinical pattern.390.391.392.393.394.395.396.397.398. and 399. It may, rarely, be the presenting complaint in AIDS. 400Bartonella infection has not been detected in lesions of granuloma annulare. 401 Interstitial granuloma annulare has been reported in borreliosis, 402 but it may represent a pattern related to the Borrelia infection itself.

It has been suggested that the underlying cause of the necrobiotic granulomas is an immunoglobulin-mediated vasculitis. 403 In a recent study, neutrophils and neutrophil fragments were commonly present in early lesions but a true vasculitis was rare. Direct immunofluorescence studies did not demonstrate immune deposits in vessel walls. 404 Other studies have stressed the importance of cell-mediated immune mechanisms with a delayed hypersensitivity reaction of T helper (Th) 1 type against as yet undefined antigens.405. and 406. This is supported by the finding of increased levels of interleukin (IL)-18, interferon gamma, and IL-2 in lesional skin. 407 Collagen synthesis is increased in the lesions of granuloma annulare, probably representing a reparative phenomenon. 408

There is no therapy of choice for granuloma annulare, and the most widely used drugs are topical and systemic corticosteroids, but they are not always effective, and relapses may occur when they are discontinued. 406 Other therapies have included cryosurgery, laser, 409 retinoids, 410 vitamin E and a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, 411 dapsone, chloroquine, ultraviolet A1 phototherapy,406. and 412. and narrowband ultraviolet B therapy. 413 A combination of systemic isotretinoin and topical pimecrolimus 1% cream has been used successfully in the generalized form. 414 Imiquimod cream has been used but it produced considerable localized inflammation. 415 T-cell directed therapies such as infliximab, efalizumab, and etanercept have been used in recalcitrant cases.407. and 416. Hydroxyurea may be a viable option for the treatment of recalcitrant cases of disseminated disease. 417

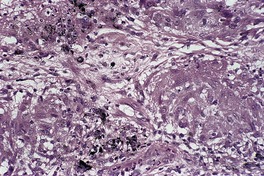

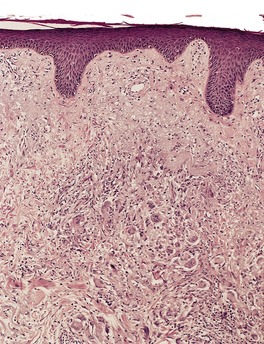

Three histological patterns may be seen in granuloma annulare – necrobiotic (collagenolytic) granulomas, an interstitial or ‘incomplete’ form, and granulomas of sarcoidal or tuberculoid type. The third of these patterns is uncommon. 418 In most histopathological studies, the interstitial form is most common. 419

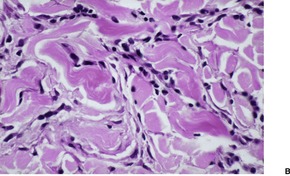

In the form with necrobiotic (collagenolytic) granulomas, one or more areas of necrobiosis, surrounded by histiocytes and lymphocytes, are present in the superficial and mid dermis (Fig. 7.6). The peripheral rim of histiocytes may form a palisaded pattern (Fig. 7.7). Variable numbers of multinucleate giant cells are found in this zone. Some histiocytes have an epithelioid appearance. An increased mitotic rate is found in the histiocytes in some cases. 420 The histiocytes are CD68+. 299 Surprisingly, in one series, the histiocytic component of the infiltrate stained only for vimentin and lysozyme and not the other common histiocyte markers (HAM56, CD68 (KP1), Mac-387, and factor XIIIa). 421 PGM1, the most specific histiocytic marker, is strongly expressed in all cases.422. and 423. The intervening areas of the dermis between the necrobiotic granulomas are relatively normal compared with necrobiosis lipoidica, and there is no fibrosis. A perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes is also present; eosinophils are found in 40–66% of cases but plasma cells are rare.424. and 425. In contrast, plasma cells are not uncommon in necrobiosis lipoidica. The central necrobiotic areas contain increased amounts of connective tissue mucins which may appear as basophilic stringy material between collagen bundles. Neutrophils and nuclear dust contribute to the basophilic appearance. Based on these changes, Lynch and Barrett have classified granuloma annulare as a ‘blue’ granuloma, in contrast to the ‘red’ necrobiotic (collagenolytic) granulomas in which fibrin, eosinophils, or flame figures contribute to an eosinophilic appearance.282. and 426. Although this is an oversimplification of a sometimes difficult assessment, the various ‘blue’ and ‘red’ granulomas are listed in Table 7.2. Special stains such as colloidal iron and Alcian blue aid in the demonstration of mucin. Heparan sulfate is present in addition to hyaluronic acid.427. and 428. Elastic fibers may be reduced, absent, or unchanged in the involved skin.429. and 430. The colocalization of granuloma annulare and mid-dermal elastolysis has been reported. 431

Granuloma annulare. The inflammatory cell infiltrate surrounds the area of ‘necrobiosis’ (collagenolysis) on all sides. It is not ‘open ended’ as in necrobiosis lipoidica. (H & E)

Granuloma annulare. (A) A palisade of inflammatory cells surrounds the central zone of ‘necrobiosis’ (collagenolysis). (B) There is some nuclear dust within this central zone. (H & E)

Occasionally, neutrophils or nuclear fragments are present in necrobiotic areas. 404 In the rare follicular-pustulous form there are neutrophils in the upper portion of the follicles leading to pustule formation. 288 Palisading necrobiotic granulomas surround hair follicles. 432 An acute or subacute vasculitis has been described in or near foci of necrobiosis, associated with varying degrees of endothelial swelling, necrosis of vessel walls, fibrin exudation, and nuclear dust. 403

The lesions of subcutaneous or deep granuloma annulare have areas of necrobiosis which are often larger than in the superficial type (Fig. 7.8). These foci are distributed in the deep dermis, subcutis and, rarely, deep soft tissues.315. and 433. There may be overlying superficial dermal lesions. Eosinophils are said to be more common in this variant than in the superficial lesions.

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. There are large areas of ‘necrobiosis’ surrounded by a palisade of lymphocytes and histiocytes. (H & E)

In the juxta-articular nodular form of granuloma annulare (pseudorheumatoid nodules) there are deep dermal nodules with subcutaneous extension composed of epithelioid granulomas separated by thickened collagen bundles. Eosinophilic material, composed predominantly of collagen, is surrounded by histiocytes in a palisaded array. This contrasts with rheumatoid nodules where the central material is fibrin, and the usual form of granuloma annulare, in which it is mucin. Scanty mucin is often present in this juxta-articular form. The interstitial form of granuloma annulare is present next to the nodules in about half of the cases, further support for the notion that the nodular lesions are a form of granuloma annulare. 316

In the disseminated form of granuloma annulare, the granulomatous foci are often situated in the papillary dermis (Fig. 7.9). Necrobiosis may be inconspicuous. There is some superficial resemblance to lichen nitidus (see p. 45), although in disseminated granuloma annulare there are no acanthotic downgrowths of the epidermis at the periphery of the lesions.

Disseminated granuloma annulare with involvement of the papillary dermis. There are no acanthotic downgrowths of rete pegs at the margins of the inflammatory focus, as seen in lichen nitidus. ‘Necrobiosis’ may be subtle in this form of granuloma annulare. (H & E)

In the interstitial or ‘incomplete’ form of granuloma annulare, the histological changes are subtle and best assessed at lower power. The dermis has a ‘busy’ look due to increased numbers of inflammatory cells, mainly histiocytes and lymphocytes (Fig. 7.10). They are arranged about vessels and between collagen bundles which are separated by increased connective tissue mucin. There are no formed areas of necrobiosis. In some cases the interstitial component is minimal. A similar appearance can be seen in the interstitial granulomatous drug reaction (see p. 192) although in the latter condition true necrobiosis is uncommon, and, if present, localized. Furthermore, eosinophils are often present and there may be lichenoid changes at the dermal–epidermal interface. In interstitial granulomatous dermatitis there are both neutrophils and eosinophils in the infiltrate, although both cell types may be sparse. Another characteristic feature is the presence of a palisade of histiocytes around one or many collagen fibers, which often have a basophilic hue. Rarely, Mycobacterium marinum infection of the skin may mimic interstitial granuloma annulare. 434 It is uncertain whether the cases of this type of granuloma annulare associated with borreliosis are mimics or true examples of granuloma annulare. 402 Other mimics include granulomatous mycosis fungoides and B-cell lymphoma. 435 Negative staining for both hemosiderin and human herpesvirus 8 can be used to distinguish interstitial granuloma annulare from early Kaposi’s sarcoma in which both are usually positive. 436

(A) Granuloma annulare of ‘incomplete’ type. (B) The dermis is hypercellular (a so-called ‘busy dermis’). (H & E) (C) There is an increased amount of interstitial mucin. (Alcian blue)

Cases of the non-necrobiotic sarcoidal or tuberculoid type of granuloma annulare are uncommon and pose a diagnostic problem. The presence of increased dermal mucin or eosinophils may be helpful distinguishing features (Fig. 7.11). Eosinophils and obvious mucin are not seen in sarcoidosis. 424 However, granuloma annulare and sarcoidosis have been reported in the same patient. 437

Sarcoidal granuloma annulare. A single field can closely resemble sarcoidosis, although the granuloma is not completely ‘naked’. (H & E)

In most cases of granuloma annulare, the epidermal changes are minimal. Perforating lesions have a central epidermal perforation which communicates with an underlying necrobiotic granuloma (Fig. 7.12). At the edges of the perforation there are varying degrees of downward epidermal hyperplasia to form a channel. The channel contains necrobiotic material and cellular debris. There is surface hyperkeratosis. 285 The lesions sometimes perforate by way of a hair follicle. 438 Pustules are a very rare finding in the perforating variant. 288

Perforating granuloma annulare. (H & E)

Immunofluorescence studies have shown fibrin in areas of necrobiosis. 437 IgM and C3 were present in blood vessel walls in one series. 403 Immunoperoxidase techniques have demonstrated activated T lymphocytes with an excess of helper/inducer phenotype (CD4+) and CD1-positive dendritic cells related to Langerhans cells in the perivascular and granulomatous infiltrates. 405 In contrast, lymphocytes were predominantly of CD8 type in a patient with HIV infection. 439 A study of the staining pattern of lysozyme in the inflammatory cell infiltrate suggests that this may be useful in distinguishing granuloma annulare from other necrobiotic granulomas. 440 The distribution of the inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 is different in granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica. 441

Ultrastructural studies have confirmed the presence of histiocytes in the dermal infiltrate together with cellular debris and fibroblasts. Degenerative changes in collagen in areas of necrobiosis include swelling, loss of periodic banding, and fragmentation of fibers. Elastic fibers also show degenerative changes. Fibrin and other amorphous material is present in interstitial areas. 442

Necrobiosis lipoidica was originally called ‘necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum’ but, although some cases are associated with diabetes mellitus,443. and 444. it is not peculiar to diabetes. 445 In one series only 11% of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica had diabetes mellitus at presentation, while a further 11% developed impaired glucose tolerance/diabetes in the succeeding 15 years. 446 The incidence in diabetics is low – approximately 3 cases per 1000. 443 It is even lower in childhood diabetes. 447

The legs, particularly the shins, are overwhelmingly the commonest site of involvement, but lesions may also occur on the forearms, hands, and trunk. Unusual sites include the nipple, penis, surgical scars, and a lymphedematous arm.448.449.450.451.452. and 453. Three-quarters of cases are bilateral at presentation and many more become bilateral later. Lesions may be single but are more often multiple. Diffuse disease is rare. 454 Females are affected more than males in a ratio of 3 to 1. The average age of onset in one series was 34 years, but the condition may be seen in children.455. and 456. It has occurred in monozygotic twins, but not until adult life. 457

The earliest lesions are red papules which enlarge radially to become patches or plaques with an atrophic, slightly depressed, shiny yellow-brown center and a well-defined raised red to purplish edge. Nodules are uncommon. 458 Some lesions resolve spontaneously but many are persistent and chronic and may ulcerate;459.460. and 461. this occurred in 13% of cases in one series. 462 Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma may arise in long-standing lesions.463.464.465.466.467. and 468. The simultaneous occurrence of necrobiosis lipoidica with granuloma annulare469. and 470. and with sarcoidosis has been reported.471. and 472. It has also been associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and jejunoileal bypass surgery. 473 The case reported in association with light-chain-restricted plasma cellular infiltrates473. and 474. has been questioned by others as not representing necrobiosis lipoidica. 475

The association of these lesions with diabetes has already been referred to but the role of this metabolic disorder in the development of the cutaneous lesions is not understood. Diabetic vascular changes may be important: in some early lesions a necrotizing vasculitis has been described. 476 Lesions show increased blood flow, refuting the hypothesis that the disease is a manifestation of ischemic disease. 477 The finding in areas of sclerotic collagen of Glut-1, a protein responsible for glucose transport across epithelial and endothelial barrier tissue, raises the possibility that a disturbance in glucose transport by fibroblasts may contribute to the histological findings. 478 Adults and children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and necrobiosis lipoidica are at high risk for diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. 479 The recent detection of spirochetal organisms in patients with this disease from central Europe, by focus floating microscopy, points to an involvement of B. burgdorferi or other strains in the development of this disease. 480

The treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica is suboptimal. It has included topical and intralesional steroids, antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin and ticlopidine, and drugs that decrease blood viscosity such as pentoxifylline. 481 Thalidomide, 481 topical PUVA therapy, 482 UVA1 phototherapy, 483 photodynamic therapy, 484 methotrexate, 485 topical granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), 486 and pioglitazone487 have all been used with some improvement of the disease. Antimalarial agents such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have resulted in the clearance of lesions, particularly if used in the early stages of their evolution. 488

The histopathological changes in necrobiosis lipoidica involve the full thickness of the dermis and often the subcutis (Fig. 7.13). Early lesions are not often biopsied. They are said to show a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis. Similar changes are present in septa of adipose tissue. A necrotizing vasculitis with adjacent areas of necrobiosis and necrosis of adnexal structures has also been seen. 476

Necrobiosis lipoidica. There is involvement of the full thickness of the dermis with extension into the subcutis. (H & E)

In active chronic lesions there is some variability between cases. The characteristic changes are seen at the edge of the lesions. These changes involve most of the dermis but particularly its lower two-thirds. Areas of necrobiosis may be extensive or slight: they are often more extensive and less well defined than in granuloma annulare (Fig. 7.14). The intervening areas of the dermis are also abnormal. Histiocytes, including variable numbers of multinucleate Langhans or foreign body giant cells, outline the areas of necrobiosis. The necrobiosis tends to be irregular and less complete than in granuloma annulare. There is a variable amount of dermal fibrosis and a superficial and deep perivascular inflammatory reaction which, in contrast to the usual picture in granuloma annulare, includes plasma cells (Fig. 7.15). Occasional eosinophils may be present. 424 In some cases necrobiotic areas are less frequent and there are collections of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleate cells, particularly about dermal vessels. The dermal changes extend into the underlying septa of the subcutis and into the periphery of fat lobules. This septal panniculitis may resemble erythema nodosum but in that condition there are no significant dermal changes. Lymphoid cell aggregates, containing germinal centers, are present in the deep dermis or subcutis in approximately 10% of cases of necrobiosis lipoidica. 489

Necrobiosis lipoidica. There are several layers of ‘necrobiosis’ within the dermis. (H & E)

(A) Necrobiosis lipoidica. (B) A perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrate is present in the dermis. There is ‘necrobiosis’ of the adjacent collagen. (H & E)

In old atrophic lesions and in the center of plaques there is little necrobiosis and much dermal fibrosis. The underlying subcutis is also fibrotic. Elastic tissue stains demonstrate considerable loss of elastic tissue. Scattered histiocytes may be present.

The presence of lipid in necrobiotic areas (demonstrated by Sudan stains) has been used in the past to distinguish necrobiosis lipoidica from granuloma annulare, but subsequent studies have also shown lipid droplets in granuloma annulare. 430 Cholesterol clefts may be present, uncommonly, in areas of necrobiosis.448. and 490. Rarely they are a conspicuous feature.458. and 491. Fibrin can also be demonstrated in necrobiotic areas. 444 There may be small amounts of mucin in the affected dermis but the presence of large amounts in areas of necrobiosis favors a diagnosis of granuloma annulare.

Vascular changes are more prominent in necrobiosis lipoidica, particularly in the deeper vessels. 283 These range from endothelial swelling to a lymphocytic vasculitis and perivasculitis. Epithelioid granulomas may be present in the vessel wall or adjacent to it. In old lesions the wall may show fibrous thickening. The smaller, more superficial vessels are increased in number and telangiectatic. Apart from atrophy and ulceration, epidermal changes are unremarkable in necrobiosis lipoidica. Transepidermal elimination of degenerate collagen has been reported;491. and 492. it may be associated with focal acanthosis or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Transfollicular elimination also occurs. 493

Although in most cases it is possible to distinguish necrobiosis lipoidica from granuloma annulare, there are cases in which this is difficult both clinically and histologically. 444 There may also be difficulties distinguishing between necrobiosis lipoidica and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (see below). Cholesterol clefts and transepidermal elimination may occur in both these conditions. Clinical features are usually distinctive in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but not all cases are associated with paraproteinemia or a periorbital distribution of lesions.490. and 494.

Immunofluorescence studies have demonstrated IgM and C3 in the walls of blood vessels in the involved skin. Fibrin is seen in necrobiotic areas. IgM, C3, and fibrinogen may be present at the dermoepidermal junction. 495

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare condition characterized by the presence of violaceous to red, partly xanthomatous plaques and nodules; there is a predilection for the periorbital area. A paraproteinemia is often present. The clinical course is chronic. It is discussed further in Chapter 40, page 958.

There are broad zones of hyaline necrobiosis as well as granulomatous foci composed of histiocytes, foam cells, and multinucleate cells (Fig. 7.16). The amount of xanthomatization is variable. Distinction from necrobiosis lipoidica is sometimes difficult on a small biopsy, but the clinical features of these two conditions are quite different.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. The ‘necrobiosis’ is only focal. Numerous giant cells are present. (H & E)

Skin manifestations, including rheumatoid nodules, are relatively common in rheumatoid arthritis.498. and 499. These nodules occur in approximately 20% of patients, usually in the vicinity of joints. Sited primarily in the subcutaneous tissue, they may involve the deep and even the superficial dermis. They vary from millimeters to centimeters in size and consist of fibrous white masses in which there are creamy yellow irregular areas of necrobiosis. Old lesions may have clefts and cystic spaces in these regions. It is most probable that rheumatoid nodules result from a vasculitic process; however, even in very early lesions such a change may be difficult to demonstrate. 500 Nodules usually persist for months to years. Rarely, similar lesions occur in systemic lupus erythematosus.501.502. and 503.

Multiple small nodules may develop on the hands, feet, and ears during methotrexate therapy. 504 This event is known as ‘accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis’. The term rheumatoid nodulosis has also been used for the presence of subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules with recurrent articular symptoms but no significant synovitis. The rheumatoid factor is often negative.505. and 506. The distinction of this entity from juxta-articular pseudorheumatoid nodules is problematic. 506