33 The Effects of Gynecologic Cancer on Lower Urinary Tract Function

Understanding the association between urinary incontinence and gynecologic malignancy is hampered on many levels. Age is an important confounder of this association because age influences the occurrence of both pelvic malignancy and urinary incontinence. At the treatment level, differences in surgical and radiotherapy technique also blur any association. To date, most research on the association of urinary incontinence and gynecologic malignancy has examined the effects of radical hysterectomy and pelvic radiation on bladder function. Few studies have been done on the effects of vulvar cancer and radical vulvectomy on the bladder and urethra. No studies have been done on the lower urinary associations of ovarian cancer reflecting a tumor biology and treatment that largely excludes the bladder. Table 33-1 outlines how each gynecologic cancer is linked with the classifications of urinary incontinence.

Table 33-1 Gynecologic Cancers in Relation to Functional Classification of Urinary Incontinence

Bladder Dysfunction |

THE EFFECTS OF INTRAFASCIAL HYSTERECTOMY ON LOWER URINARY TRACT FUNCTION

Intraoperative Injuries to the Lower Urinary Tract During Hysterectomy

The bladder is the most commonly injured urinary structure for both benign and cancer gynecologic surgery. Overall, the average incidence of bladder injury from major gynecologic surgery (the majority from hysterectomy) is 0.8%. In a Finnish study by Makinen et al. (2001) of greater than 10,000 hysterectomies, the rate of bladder injury was 0.2%, 0.5%, and 1.3% for vaginal, abdominal, and laparoscopic hysterectomy, respectively. The ureter is the second most commonly injured organ during major gynecologic surgery with abdominal hysterectomy accounting for 86% of all injuries. The Finnish study, reflecting a trend seen among other studies, found the ureter injury rate for vaginal hysterectomy was 0%; after abdominal and laparoscopic hysterectomy, it was 0.2% and 1.1%, respectively.

Applying these lessons to the treatment of gynecologic malignancies is complicated by the added complexity and morbidity of lymph node sampling that may be added to the “standard” intrafascial hysterectomy. Offsetting any rise in urologic injuries that may occur because of this added complexity is the overall better surgeon skill among gynecologic oncologists. The role of laparoscopy in gynecologic oncology remains debatable despite having perhaps more opportunity to add real clinical advantages because of longer hospital stays. Those who promote laparoscopic management of select gynecologic malignancies generally have skills that favor any comparisons between their laparoscopic and open surgical outcomes, and these outcomes may not be generalizable to all surgeons. Because the available data on use of intrafascial hysterectomy in treatment of gynecologic malignancy come in large part from such advocates, the reported equivalent urologic complication rates between open and laparoscopic intrafascial hysterectomy for treatment of gynecologic cancer may be with some degree of bias. In a retrospective review of 56 patients who underwent laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer treated primarily with vaginal (n = 44) or laparoscopic hysterectomy (n = 12), Magrina et al. (1999) reported a 2.3% urologic injury rate for the vaginal approach and an 8.3% rate among the laparoscopic approach. One additional bladder injury occurred with the laparoscopic lymphadenectomy portion of the procedure and would further increase the rate of urologic complications from the laparoscopic approach. These rates of urologic injury are higher than those seen with benign disease, presumably because of a higher degree of surgical complexity; however, the overall trend between the surgical approaches matches that seen for benign disease.

Postoperative Effects of Hysterectomy on the Lower Urinary Tract

Of the available studies on the postoperative effects of hysterectomy on the lower urinary tract, only one is randomized and all are limited by small size (between 16 and 72 subjects) and short duration (all but one 6 months or less). The message from these studies is conflicted. A minority of studies documents some bladder dysfunction following hysterectomy, whereas the majority finds either no effect or improvement in bladder function. The minority view holds that, with hysterectomy, there is a disruption of the autonomic and sensory nerves to the bladder—a view more substantiated with radical hysterectomy. Retrospective reviews of incontinent patients have uncovered an association between women symptomatic for some lower urinary tract dysfunction (e.g., incontinence, voiding dysfunction) and hysterectomy. A large population study by Brown et al. (1996) investigating this issue queried 7949 American women over the age of 65 and found daily urinary incontinence was more common in women who had had previous hysterectomy than those who had not (adjusted odds ratio 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–1.6). Among these retrospective studies, the variability in definitions of urinary incontinence and the unknown indications for hysterectomy (e.g., pelvic organ prolapse) make interpretation of their results difficult. Furthermore, these studies are hindered by selection and/or recall bias.

Weber et al. (1999), in a prospective study of 43 women before and after hysterectomy, found no change in reported stress or urge incontinence at a mean follow-up of 14.2 months. Yet studies that find either no association or a beneficial effect of hysterectomy on bladder function could suffer from inadequate follow-up times to uncover the issues seen in the long-term population-based studies. Notably, a number of studies have compared urodynamic findings before and after hysterectomy and all have found no significant changes in mean cystometric capacity, occurrence of spontaneous detrusor contractions, post-void residual volumes, or uroflowmetry values. Taken together, the quality evidence available to date supports the conclusion that intrafascial hysterectomy is unlikely to cause any lower urinary tract dysfunction in the short term and any long-term effects are unclear.

THE EFFECTS OF RADICAL HYSTERECTOMY ON LOWER URINARY TRACT FUNCTION

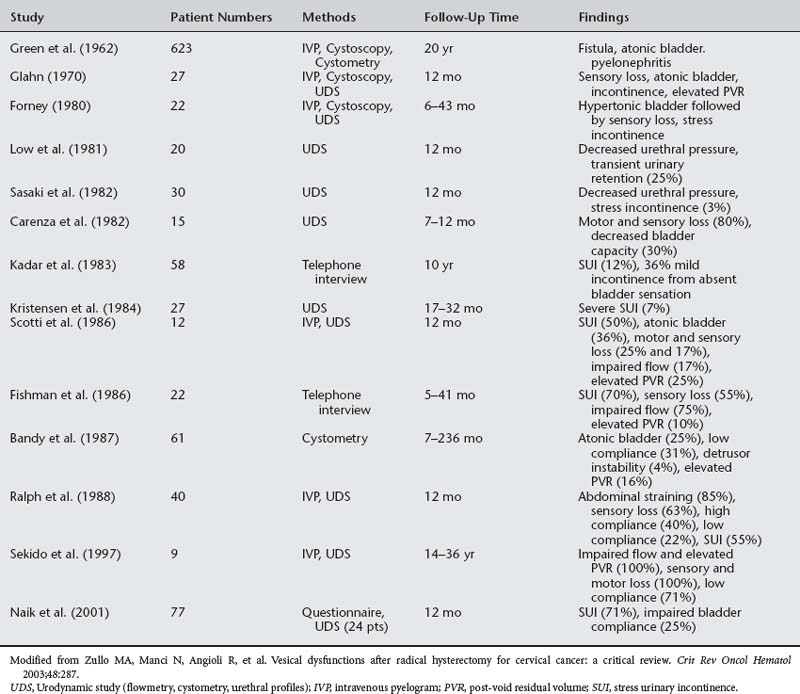

The radical hysterectomy introduced by Wertheim in 1912 has proved to be an effective treatment for early-stage cervical cancer. Fortunately, many of the early morbidities have been ameliorated. In Wertheim’s original series, 6.8% of patients developed vesicovaginal fistulas and 6.4% developed ureterovaginal fistulas. Lesser morbidities such as urinary incontinence were not considered. Today, however, with a fistula rate of approximately 1%, urinary incontinence has become the dominant surgery-related morbidity. Rates of lower urinary tract dysfunction following radical hysterectomy range between 20% and 80%. Types of lower urinary tract dysfunction following radical hysterectomy include voiding dysfunction (e.g., abdominal straining, slow flow), storage dysfunction (e.g., decrease capacity or sensation, elevated postvoid residual volumes), recurrent urinary tract infections, and urinary incontinence. Table 33-2 lists the kinds and frequency of urologic complications following radical hysterectomy. Urinary incontinence of various types occurs in 20% to 50% of patients following radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer with between 5% and 12% of individuals severely handicapped by the disorder. Notably, one study found that 35% of patients were unhappy with their urinary dysfunction following radical hysterectomy, although all were satisfied with their post-treatment cancer outcomes. This likely reflects an acceptance of presumed necessary morbidities of aggressive cancer treatment. The following will consider the specific bladder and urethral effects of radical hysterectomy.

Bladder Dysfunction

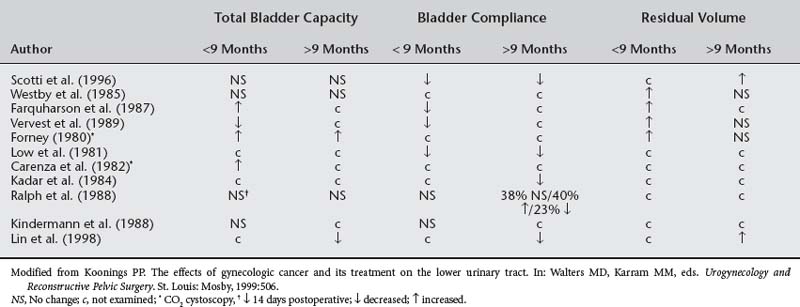

Despite Scotti et al. (1986) documenting stable bladders on urodynamic studies of women following radical hysterectomy, the majority of studies report abnormal spontaneous contractions of the bladder. A number of studies have shown decreased bladder compliance and resultant increased bladder pressures in patients following radical hysterectomy. Table 33-3 lists these reported urodynamic bladder changes following radical hysterectomy. These findings, however, are usually transient with spontaneous resolution or development of bladder areflexia and overflow incontinence over the following year. Both Lerner et al. (1980) and Kadar et al. (1983) reported patients with permanent inability to void following radical hysterectomy, presumably from atonic bladder. In a study of women who had underwent a radical hysterectomy no less than 10 years prior, Minini et al. (1992) found 18 of 20 had absent bladder contractility requiring abdominal straining to void. Detrusor function can be impaired irrespective of intravesical pressure. Decreased bladder compliance and increased intravesical pressure would be expected to correspond with increased flow rates and less residual urine, but this is not always the case following radical hysterectomy.

The etiologies of bladder and urethral effects after radical hysterectomy are difficult to decipher. Several studies have investigated the effects of sparing some portion of the cardinal ligaments on bladder function. The concept has merit as studies confirm the presence of abundant nerve tissue in the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, particularly at their site of origin along the pelvic sidewall. Forney (1980), Sasaki et al. (1982), and Kadar et al. (1983) all documented less-impaired bladder function among patients undergoing radical hysterectomy in whom portions of the cardinal ligaments were preserved. The inferior hypogastric plexus consists mainly of parasympathetic fibers from sacral roots S3 and S4 as well as some sympathetic fibers from the lumbosacral trunk. These nerves are present at least in part in the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments, and supply the large bowel (to the level of the internal anal sphincter), the bladder and urethra, and the entire genital tract. Division of these nerves during radical hysterectomy alters the neurologic control of the lower urinary tract, resulting in dysfunction. In 1973, Roman-Lopez and Barclay postulated that parasympathetic overdominance following radical hysterectomy accounted for the initial bladder dysfunction. However, this theory fell into disfavor when parasympatholytic agents did not reverse the bladder effects. Alternatively, Forney (1980) argued that damage to the sympathetic portion of the hypogastric plexus accounted for the bladder dysfunction. Difficulty with this mechanism, however, arises in more current investigations such as Scotti et al. (1986) that did not find any correlation between the radicality of the surgery and any lower urinary tract dysfunction. Moreover, Kindermann and Debus-Thiede (1988)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree