25 Constipation

DEFINITION AND ETIOLOGY

Because most constipation becomes a problem only when the patient complains of it, and because symptoms of constipation may occur in the absence of any physiologic abnormalities (i.e., stool frequency does not necessarily correlate with transit time), a symptom-based definition still holds some value and has become the standard. This led to the development of the ROME criteria (Drossman et al., 2000). The criteria are expert consensus guidelines for making the clinical diagnosis of the various types of functional bowel disorders, including constipation. The criteria have become the standard for the definition of constipation.

The ROME III criteria divide patients complaining of symptoms of constipation into two major groups: functional bowel and functional anorectal disorders. Functional bowel disorders include: (1) functional constipation and (2) irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). Subjects with functional constipation often complain of fewer than three bowel movements per week, hard or lumpy stools, straining, feeling of incomplete emptying after a bowel movement, a sensation that stool cannot be passed, or a need to press on or around their bottom or vagina to complete a bowel movement. Functional constipation may include patients who demonstrate slowed transit times on colonic transit studies or patients with idiopathic constipation because it is a symptom-based diagnosis. The diagnostic criteria for functional constipation are seen in Box 25-1. Patients with IBS-C have the same symptoms, except they often have abdominal pain. This pain is associated with improvement after a bowel movement, change in the number of bowel movements, or change in consistency of stools. Some experts felt that constipation could be broken down into further subtypes based on the reported predominant evacuation symptoms, including IBS-outlet and outlet-type constipation. A subcategory of patients who fulfilled criteria for either constipationpredominant IBS or functional constipation also report one of the following evacuation symptoms: a sensation that stool cannot be passed when having a bowel movement, a need to press on or around their bottom or vagina to try to remove stool to complete a bowel movement, or difficulty relaxing or letting go to allow the stool to come out at least one quarter of the time. These subtypes are now referred to as functional defecation disorders. Functional defecation disorders (often referred to as evacuation disorders, outlet dysfunction or delay, or pelvic floor dysfunction) have been incorporated into the ROME III criteria and include (1) dyssynergic defecation and (2) inadequate defecatory propulsion. The diagnostic criteria for functional defecation disorders are:

BOX 25-1 ROME III DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION

From Longstreth GE. Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders.Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480.

The pathophysiology of constipation continues to evolve. Investigators have attempted to examine the relationships between slow transit disorders and external neuropathy conditions, such as spinal cord injury patients, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes. The premise behind these disorders is that the symptoms of constipation result from motor and sensory disturbances, ultimately leading to delayed transit or physiologic disorders of the colon and pelvic floor. Neuropathy of the enteric nervous system may also occur in patients with Chagas’ disease secondary to infection from Trypanosoma cruzi, Hirschsprung’s disease, or chronic laxative abuse. Studies of the pathophysiology of disorders of defecation have examined altered anorectal motor and sensory function. These include studies involving perceptual responses to controlled rectal distension, alterations to visceral sensation, and pudendal nerve terminal motor latencies. For example, there is evidence that dyssynergia of the puborectalis and external anal sphincter muscles during defecation, leading to outlet dysfunction and constipation in patients with multiple sclerosis, is due to a spinal lesion. Mathers et al. (1989) showed that this functional abnormality also occurred in patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease, and that in Parkinson’s disease it was responsive to dopaminergic medication. De Groat et al. (1990) showed that interruption of pathways in the spinal cord can result in detrusor sphincter dyssynergia, and it is therefore likely that paradoxical puborectalis contraction in multiple sclerosis is due to interruption of spinal pathways by demyelination. The data provide evidence that functional bowel disorders may be more intimately associated with the neurologic system than is commonly thought. Despite these advances, our knowledge of neuroanatomy and its relationship to functional disorders of the bowel remains in its infancy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Constipation is a commonly encountered problem in medical practice and is expected to increase dramatically. The U.S. population is becoming older and more likely to be living with chronic neurologic disease and to reside in nursing homes. Estimates of incidence and prevalence vary depending upon the definition used (i.e., self-reported constipation or ROME criteria) and the population studied. The data available on incidence of constipation are few. Talley et al. (1992) showed the onset of constipation of 40 per 1000 person-years in white residents of a single county in Minnesota. The symptom remission rate was 309 per 1000 person-years. Stewart et al. (1999), in a large U.S. epidemiologic study containing over 10,000 individuals, found an overall constipation prevalence of 14.7% in the general population. Higgins et al. (2004), in a systematic review of the epidemiology of constipation in North America, concluded that a conservative estimate of 15% of the North American population, or 42 million individuals in the United States alone, suffer from constipation.

Subtypes of constipation among the U.S. population in men and women showed functional constipation in 4.6%, constipation-predominant IBS in 2.1%, outlet subtype constipation in 4.6%, and IBS-outlet subtype in 3.6% (Stewart et al., 1999). Overall, women had higher rates of outlet disorders. However, when these constipation subtypes were broken down among gender, the only statistical difference was in women being more likely to have IBS-outlet subtype of constipation. Higgins et al. (2004), in the large systematic review, concluded that the prevalence of constipation stratified by gender showed constipation to be approximately 2.2-fold more frequent in women. Most of the studies that stratified by age found consistent trends of increasing prevalence of constipation with age, with significant increases after age 70. Interestingly, when Sandler et al. (1987) stratified by subtypes of constipation in women by age, the prevalence of constipation actually decreased as they got older.

Most data suggest similar racial differences in the prevalence of constipation, with an average prevalence of 1.17- to 2.89-fold more frequent in non-Caucasians than in Caucasians. Outlet-type constipation was also more prevalent among nonwhites in the data from Sandler et al. (1987).

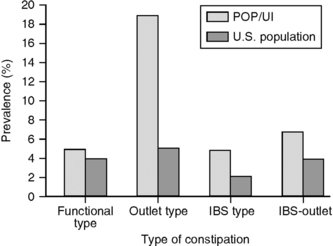

At our institution, over 300 women who presented to a urogynecology clinic for either pelvic organ prolapse or incontinence had an overall prevalence of constipation of 36%, as defined by the ROME II criteria. When this sample was stratified by subtype, 5% had functional constipation, 19% outlet type, 5% constipation-predominant IBS, and 7% IBS-outlet type (Fig. 25-1). Given recent population shifts in North America, constipation and its associated outlet disorders make this a condition with which gynecologists and urologists should be familiar.

EVALUATION

History

Ruling out associated medical problems that may lead to secondary constipation (Box 25-2) is important. Constipation is more common in people with neurologic disease, such as multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. Diabetes may also be associated with constipation. Recent changes in routine, such as levels of diet and exercise, may contribute to constipation. Self-reported constipation is higher in individuals with the least exercise (odds ratio [OR] = 1.2–3.3). Sandler et al. (1987) found that decreased caloric intake favored constipation with an OR of 1.15. In patients with severe constipation and no obvious cause, histories of physical and/or sexual abuse may be found.

Physical Examination

Few clinicians would dispute the association between vaginal prolapse and symptoms of constipation, although a direct relationship between the two is not clear. In 1998, Weber et al. described 143 women who completed a questionnaire assessment of bowel function with standardized examinations, using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) method. In 26.6% it was rare to require straining to have a bowel movement, in 49.6% straining was sometimes required, in 14% straining was usually required, and in 9.8% straining was always required. Thirty-one percent needed to help stool come out by pushing with a finger in the vagina or rectum. Severity of prolapse was not related to bowel dysfunction. In a Swedish population of 491 women, when a rectocele was present, 18% reported problems with emptying the bowel at defecation compared with 13% in the nonrectocele group (Samuelsson et al., 1999). However, constipation was not related to prolapse in this population.