Recognition of the brow as an integral contributor to periocular appearance improves and prolongs results from facial rejuvenation surgery. The approach to the brow and forehead in periocular rejuvenation must be chosen on an individual basis. The approaches discussed require in-depth knowledge of complex forehead and temporal anatomy to navigate the planes and important neurovascular structures safely. This article discusses anatomy, preoperative evaluation and considerations, surgical techniques, and complications in rejuvenation of forehead and brow.

The periorbital region is often the first facial area to manifest signs of aging. The eyes may appear heavy or tired long before an individual experiences jowling or frank rhytids. The delicate anatomy of the eyes and periocular area make it more amenable to showing the signs of aging. Youthful patients have a full or volumized appearance to their skin, with notable subcutaneous fat. The thin skin of the upper and lower eyelids is nearly anatomically devoid of this subcutaneous fat and thus has less of a buffer to the early signs of aging.

In the past, the periocular and brow regions were inadequately addressed in facial rejuvenation surgery. The effect that the brow and forehead have on periocular and upper facial aging has not always been a priority. Contemporary surgeons have come to realize that one cannot improve the appearance of the upper eyelid if the brow is ptotic and continues to encroach upon the upper eyelid. If brow ptosis is present and not addressed, the periocular region continues to look heavy with a fatigued appearance.

The forehead, invariably linked with brow ptosis, has additional contributions to the aged appearance. The receding hairline in men or a prominent forehead in both sexes has an effect on overall facial appearance. Kinetic forehead rhytids caused by the hypertrophic corrugator, procerus, or frontalis muscles are natural repercussions of human expression. All these 3 muscles may cause brow asymmetry.

The entire face, having been broken down into aesthetic units, merits a thorough evaluation of symmetry and substance, which vary individually with patients. What does not vary, however, is the interaction and dependence of adjacent aesthetic units.

Anatomy

The spatial position of an individual’s brow is affected by the relative contribution of brow elevator versus brow depressor muscles. The frontalis muscle is the only elevator of the brow. This muscle ends anatomically at the superior temporal line.

There are, however, multiple depressor muscles, including the procerus, corrugator, depressor supercilii, and orbicularis oculi muscles. The procerus muscle is responsible for the horizontal glabellar rhytids, and the corrugator muscle for the vertical glabellar rhytids. The frontalis muscle is contained within the galea, which is a tendinous sheet that also envelops the occipitalis muscle. The galea is relatively inelastic and extends laterally to join with the temporoparietal fascia. This transition occurs at the temporal line. Although physically separated at the zygoma, the temporoparietal fascia is anatomically congruent with the superficial muscular aponeurotic system in the lower face below the zygomatic arch.

The orbicularis oculi is divided into 3 parts: preseptal, pretarsal, and orbital portions. This division is less of an anatomic designation and more of a functional division that aids the surgeon’s decision for therapy as well as serves as a surgical landmark. The pretarsal and preseptal components are self-explanatory, lying superficial to the tarsus and the orbital septum, respectively. These muscular subunits function somewhat involuntarily with blinking and are mechanical factors in the lacrimal pump system. The orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi functions in squinting and is more of a cause for dynamic rhytids, including the crow’s feet. This orbital portion is implicated in brow ptosis, medially and laterally.

The skin of the forehead is thick and is densely adhered to the underlying subcutaneous tissue. Deep to the subcutaneous tissue is the previously mentioned galea aponeurosis containing the frontalis muscles anteriorly and the occipitalis muscle posteriorly. The galea is separated from the periosteum by loose connective tissue. The periosteum is contiguous laterally with temporalis muscle fascia at the temporal line. The periosteum of the forehead has a confluence with the orbital septum at the superior orbital rim. This dense fascia condensation is called the arcus marginalis ( Fig. 1 ). It is imperative that these decussating fibers be released for adequate and enduring brow-lift results.

Preoperative evaluation

In the preoperative evaluation, it is the surgeon’s responsibility to point out the asymmetries in brow position and the importance of the brow and its effect on the upper eyelid. The surgeon must also communicate why correcting excess lid skin and fat herniation fails in improving appearance if the ptotic brow is not addressed.

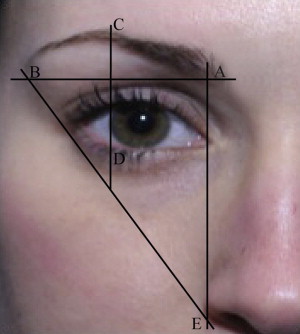

Ideal brow position varies between gender and race. Men tend to have a heavier, thicker brow, with little arc present. The brow in men lies approximately at the level of the superior orbital rim. The brow in women is more refined. In women, the brow is club shaped medially and tapers laterally. The medial border of the brow is on a vertical line with the alar-facial crease. The lateral end of the brow lies on a line drawn from the alar-facial crease tangent to the lateral canthus. The medial and lateral ends of the brow are on the same horizontal plane. The highest arch of the brow in women is ideally at the lateral limbus or just lateral to it. Ideally, the brow in women should lie just above the superior orbital rim ( Fig. 2 ).

It is important for the patient to be in complete repose during evaluation. Often, patients with brow ptosis compensate by tonic contraction of the frontalis muscle, which may result in headaches as well as horizontal forehead rhytids. To achieve full repose, it may be beneficial to ask patients to close their eyes, focus on relaxing the forehead, and gently open their eyes for a more precise analysis of brow position.

McKinney and colleagues described certain quantitative measurements to aid in selection of the appropriate lifting technique. The investigators used measurements in a vertical plane from midpupil to the top of the eyebrow and up to the hairline to indicate which procedures and approaches should be used for brow lifting. The investigators prefer to use a more individualized approach for brow and periocular evaluation, focusing on specific anatomic landmarks.

Eyelid Ptosis

It is important to note if a patient has underlying eyelid ptosis on one or both sides, which is best determined by assessing the marginal reflex distance (MRD) 1. MRD-1 is the noted distance between pupillary light reflex and the margin of the upper lid; a distance of 3.5 to 5 mm is normal. The upper lid itself should lie just below the superior limbus by approximately 1 to 1.5 mm. The MRD-2 is the distance, measured again in primary gaze, between the pupillary light reflex and lower lid margin; a distance of greater than 5 mm is adequate.

Levator Function

Levator function must also be recorded when evaluating brow ptosis. This evaluation is performed by holding the brow in position (nullifying the effect of the frontalis muscle) and requesting the patient to first look down and then up. The difference between the eyelid position looking downward and then upward is the levator function ( Fig. 3 ). If a measurement of less than 4 mm is found between maximum downgaze and maximum upgaze, the levator function is deemed as poor; a movement of 5 to 7 mm is fair, 8 to 15 mm is good, and more than 15 mm is normal ( Table 1 ).

| Levator Muscle Excursion (mm) | Functional Classification |

|---|---|

| <4 | Poor |

| 5–7 | Fair |

| 8–15 | Good |

| >15 | Normal |

Upper Lid

Upper lid evaluation is to be performed in conjunction with brow evaluation. An attenuated skin excision is appropriate after brow elevation to avoid excessive lagophthalmos. Dermatochalasia is the general term used for presence of excessive skin and its laxity associated with aging as well as fat herniation. Blepharochalasis is a rare occurrence of unknown cause that occurs typically in women and is manifest by edema, causing decreased elasticity and notable atrophic changes.

Forehead

The forehead itself may mandate the appropriate brow procedure. Deep forehead rhytids with a high hairline make midforehead lift a reasonable approach.

Patient Health

The patient’s health may also play a role in preoperative decisions. Unhealthy patients who are not suited for longer surgeries or general anesthesia may preclude more extensive procedures and elect a direct brow approach.

Preoperative evaluation

In the preoperative evaluation, it is the surgeon’s responsibility to point out the asymmetries in brow position and the importance of the brow and its effect on the upper eyelid. The surgeon must also communicate why correcting excess lid skin and fat herniation fails in improving appearance if the ptotic brow is not addressed.

Ideal brow position varies between gender and race. Men tend to have a heavier, thicker brow, with little arc present. The brow in men lies approximately at the level of the superior orbital rim. The brow in women is more refined. In women, the brow is club shaped medially and tapers laterally. The medial border of the brow is on a vertical line with the alar-facial crease. The lateral end of the brow lies on a line drawn from the alar-facial crease tangent to the lateral canthus. The medial and lateral ends of the brow are on the same horizontal plane. The highest arch of the brow in women is ideally at the lateral limbus or just lateral to it. Ideally, the brow in women should lie just above the superior orbital rim ( Fig. 2 ).

It is important for the patient to be in complete repose during evaluation. Often, patients with brow ptosis compensate by tonic contraction of the frontalis muscle, which may result in headaches as well as horizontal forehead rhytids. To achieve full repose, it may be beneficial to ask patients to close their eyes, focus on relaxing the forehead, and gently open their eyes for a more precise analysis of brow position.

McKinney and colleagues described certain quantitative measurements to aid in selection of the appropriate lifting technique. The investigators used measurements in a vertical plane from midpupil to the top of the eyebrow and up to the hairline to indicate which procedures and approaches should be used for brow lifting. The investigators prefer to use a more individualized approach for brow and periocular evaluation, focusing on specific anatomic landmarks.

Eyelid Ptosis

It is important to note if a patient has underlying eyelid ptosis on one or both sides, which is best determined by assessing the marginal reflex distance (MRD) 1. MRD-1 is the noted distance between pupillary light reflex and the margin of the upper lid; a distance of 3.5 to 5 mm is normal. The upper lid itself should lie just below the superior limbus by approximately 1 to 1.5 mm. The MRD-2 is the distance, measured again in primary gaze, between the pupillary light reflex and lower lid margin; a distance of greater than 5 mm is adequate.

Levator Function

Levator function must also be recorded when evaluating brow ptosis. This evaluation is performed by holding the brow in position (nullifying the effect of the frontalis muscle) and requesting the patient to first look down and then up. The difference between the eyelid position looking downward and then upward is the levator function ( Fig. 3 ). If a measurement of less than 4 mm is found between maximum downgaze and maximum upgaze, the levator function is deemed as poor; a movement of 5 to 7 mm is fair, 8 to 15 mm is good, and more than 15 mm is normal ( Table 1 ).