CHAPTER 1 The Art of the Surgical Technique*

Preparation for the operation

Firm plan with contingencies

Room setup

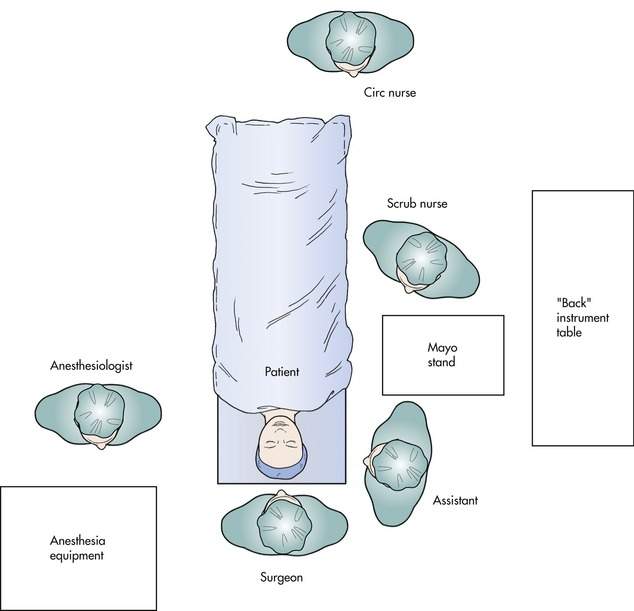

As part of your plan, you should know where the operating equipment will be placed. Generally, the setup is as shown in Figure 1-1. In most cases, the operated eye will be placed away from the anesthesia equipment. The surgeon will sit at the head of the bed. The assistant will sit at the side of the bed corresponding to the operated eye. For some procedures, you may find it easier to sit at the patient’s side (for example, lateral tarsal strip and lateral orbitotomy). Feel free to move throughout the case and be comfortable. The nursing table will be on the same side as the assistant, but to the side of the bed.

Skin marking and local anesthesia

Many oculoplastic procedures require skin marking as a guide to incision placement. The majority of incisions will be placed in natural skin creases as in the upper lid skin crease for ptosis and blepharoplasty operations. Other skin incisions will be placed adjacent to anatomic structures to hide the scar. You should mark the skin before any local anesthetic is injected. Two good choices for marking eyelid skin are available: 1) gentian violet solution and 2) surgical marking pen. Gentian violet can be applied with the sharp end of a broken applicator used as a quill. With experience, you can draw a fine line that does not easily wash off with prepping, but this takes some experience to keep from making a mess. Usually, we use a thin-tipped surgical marker (“Twin-Tip” surgeon’s marker, #6650-T, Hospital Marketing Services, Inc., http://www.hmsmedical.com). Be sure to degrease the skin with an alcohol wipe before marking.

Topical solutions are available that provide anesthesia. You should know about these two preparations: EMLA cream and Betacaine gel. EMLA cream should be applied in a thick coating 1 hour ahead and covered with an occlusive dressing (topical lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%, AstraZeneca LP, http://www.astrazeneca-us.com). Betacaine gel (topical lidocaine 5%, Canderm Pharma, Inc., http://www.canderm.com) can be applied for 20–30 minutes ahead without an occlusive dressing. Both preparations provide anesthesia, but no vasoconstriction, so usually additional local injection with epinephrine is required for surgical procedures. Topical agents are also useful prior to Botox or filler injections and can be helpful in children. Overdosing with systemic reaction is unlikely, but possible. Most of the time, I do not use these preparations, but you might find them helpful in your practice.

If your operating situation allows for the efficient use of monitored anesthesia care, your anesthesiologist can medicate your patient to the point at which there is no memory of any pain from the injection and often no memory of the entire operation. The downside of this is more staffing and increased patient cost.

Cutting the skin

Hand position

There are three tools used for cutting the skin:

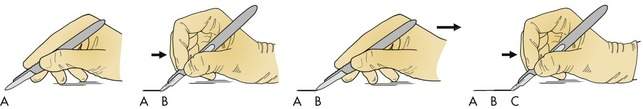

As you hold the scalpel with the pencil grip, you will notice that, on the scalpel handle, there is a groove or flat area where your index finger will rest. The scalpel is supported between your thumb, index finger, and middle finger (Figure 1-2).

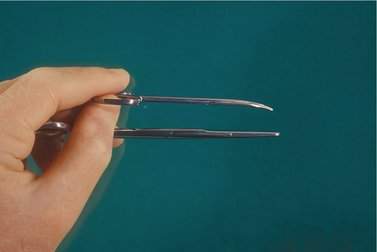

The eyelid skin is mobile. Precision cutting requires immobilization of the skin with the help of your fingers or the assistant’s fingers. Use your ring finger to rest on the patient, stabilizing the skin or guiding your hand. Learn to use the ring finger on your dominant hand and the thumb and forefinger on your nondominant hand to stabilize the skin (Figure 1-3). If the tissue is slippery, using a gauze pad for some traction will be helpful.

Figure 1-3 Skin stabilization. During upper eyelid blepharoplasty, the skin fold is stabilized and stretched with the surgeon’s fingers while the upper eyelid is drawn downward using a lid margin traction suture. Note that a Colorado microdissection needle* is being used for the incision. With experience, the traction suture can be eliminated and the surgeon can use fingers to stretch the skin tight.

It is best to start the skin incision with the tip of the scalpel blade. As you move across the incision, lay the scalpel down so that you are cutting with the curved part of a no. 15 blade. As the wound edges start to separate, observe the depth of the wound. Ideally, you want to cut eyelid skin only and not extend the cut into the orbicularis. This is difficult to do, but nevertheless worthwhile. Controlling the depth of any eyelid incision is critical. Remember that the eyelid is only slightly more than 1 mm thick at the skin crease, and you do not want to extend your incision into the cornea. You might find that using a corneal protector is a useful safeguard initially. With experience, you will probably find it easier not to use a corneal protector for scalpel cutting or cutting cautery incisions. Adjust the pressure to maintain the proper depth of the wound. Like driving a car, look “down the road,” as you pull the scalpel across the skin. All of this is happening as you or your assistant holds steady tension on the skin. Remember, tight skin can be cut more easily and accurately than more mobile skin. Like most instruments for eye surgery, the scalpel is a “finger tool.” As you bring your fingers toward your palm with the scalpel tip, you may need to reposition your hand and repeat the cutting process in lengths of the wound (Figure 1-4). As you get more experienced, you will be able to flex your fingers and move your hand at the same time.

Figure 1-4 Flexion of the fingers with the scalpel blade followed by movement of the hand

(adapted from Edgerton M, The art of the surgical technique, Baltimore, 1988, Williams & Wilkins).

Scalpel blades

• No. 11 blade: This blade has a sharp point that is good for tight angles and curves. It is not useful for longer incisions because it may cut deeper than you expect.

• No. 15 blade: This is the best all-purpose scalpel blade for eyelid and facial skin; 98% of your eyelid surgery with a scalpel will be done using a no. 15 blade.

• No. 10 blade: The no. 10 blade is shaped like a no. 15 blade except bigger. This blade is used primarily for thicker skin incisions. It is not used for periorbital incisions, but can be helpful in facial flaps.

• Beaver blades (http://www.bd.com) The #66 Beaver blade (#376600) is a special purpose right-angled blade. Its primary use is for making cuts in tight spaces. It is especially useful for nasal mucosal incisions in dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) procedures. Angled keratomes designed for anterior segment surgery work in a similar fashion (Figure 1-5). Other useful blades are the #64 blade (#376400 rounded tip, sharp on one side), #76 blade (#376700, a mini #15 blade), both useful for delicate shaving of tissue off sclera or cornea. The needle blade #375910 is good when you need to make a microincision. Beaver handles come in a variety of lengths, the most common being 10 cm. Longer length handles (13 and 15.5 cm) are useful for deep orbitotomy or craniotomy cases.

Other cutting tools

Two other useful cutting tools are available for eyelid surgery: the microdissection needle and the CO2 laser. The microdissection needle has been my choice for the majority of periocular surgical procedures in recent years. This unipolar cautery device does an excellent job of cutting and cauterizing the thin eyelid tissues. The needle is made of tungsten with an extremely fine tip. Tissue in contact with the tip is vaporized. Getting used to this instrument takes some practice. Cutting the tissue should be done with superficial light passing over the tissue in a “painting” motion with the needle slightly angled as if you are using a paint brush. If you find that carbon is building up on the tip of the instrument, you are moving too fast, you are cutting too deep, or you have the power turned up too high. The trick of using this tool is cutting only at the very tip so that there is little thermal damage to the surrounding tissues. Using a “blend” mode gives cutting and cautery. Try this for the dissection of an upper eyelid blepharoplasty skin muscle flap. Once you get used to this “bloodless” field, you will have trouble going back to scissors. You should use a smoke evacuator to eliminate the hazardous smoke produced by this tool. The patient requires grounding as with the use of other unipolar cautery equipment. The use of this unipolar cutting tool is sometimes limited to tissues anterior to the orbital septum, because the electric current is carried into the orbit and causes pain for many patients under local anesthesia. The tip works on the dry eyelid skin, but works best on tissues deep to the skin. For this reason, some surgeons prefer using a blade for the initial skin incision as the wound is sharper. I use a blade in many cosmetic cases and switch to the needle for any deeper work. You may find the Colorado needle with a foot pedal useful, but I prefer the hand switch on the cautery handle itself. Two companies make a microdissection needle (Stryker Colorado needle, Stryker Medical, http://www.stryker.com, 800 869 0770; and Tungsten microsurgical needle E1650, Valleylab, http://www.valleylab.com, 800 722 8772). The shortest length needle is the easiest to work with on periocular tissues.

The CO2 laser is also a useful tool for cutting eyelid skin. Like the microdissection needle, tissues are vaporized with excellent cautery of capillaries and small veins. The Coherent UltraPulse 5000C CO2 laser was introduced years ago and remains a work horse in my practice. The current model is the UltraPulse Encore made by Lumenis (Lumenis Inc., http://www.lumenis.com, 801 656 2300). These lasers remain the gold standard for laser incisional and resurfacing work. As when using a microdissection needle, large vessels are often cut with the laser rather than cauterized, so you will need a bipolar cautery tool on the operating room table as well. Both these cutting and cauterizing tools can shorten operating times considerably. If you have a CO2 laser available, you should try this as a cutting tool. You must emphasize “pulling apart the tissues” with your forceps. There is no “touch” or “feel” involved in the cutting. It is all visual so technique is very important. Once you learn it, you will love it. Patients have less discomfort with the CO2 laser than with the Colorado microdissection needle. Some precautions are necessary. You will need sandblasted instruments to prevent reflection of the laser energy. Metal corneal shields are a must. Surgeons and staff must wear protective goggles. Smoke evacuation is necessary. Care with oxygen and the use of wet drapes are important to prevent fire. The majority of procedures in this text will be described with the use of the microdissection needle, but I suggest you try the laser, especially for upper blepharoplasty. The skills that you will learn using the microdissection needle and the laser are complementary; learning one will help you with the other.

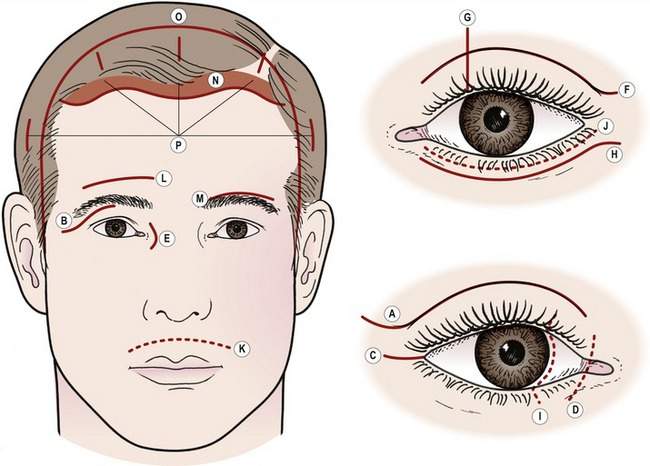

Placement of skin incisions

Most skin incisions that you will make are hidden in natural creases or wrinkle lines (Figure 1-6). The upper lid skin crease is a natural place to make incisions in the upper lid. The upper lid skin crease will often be carried laterally into a “laugh line.” If you are working away from an area where you are not familiar with the wrinkle lines, ask the patient to contract the facial muscles in that area. You will see wrinkles and folds in the skin that will show you where to place your incisions. You can anticipate these lines. Remember that the natural skin creases occur perpendicular to the direction of the muscle fibers causing this crease. Contract your frontalis muscle and you will see the furrows of the forehead perpendicular to the frontalis muscle fibers.

Anxiety and tremor

Checkpoint

• Remember to have a plan when you enter the operating room. Let the staff know what the plan is. Know what the room setup will be. Know the instruments. Your preparedness will inspire confidence and set the pace for the operation.

• You must have a plan for the operation and some contingencies if things don’t go as planned. You would be surprised how many residents come to the operating room expecting to be “shown” what to do. As a resident, the more you know, the more you will get to do, and the faster you will learn.

• Get the patient, operating table, your stool, and your body in a comfortable position before starting. Have all the equipment prepared before you make a skin incision.

• Why should you mark the skin and inject the local anesthetic before scrubbing?

• Do you need to write down the names of special instruments, sutures, or equipment that you will be using?

• Let the operating room nurses know what you are planning, especially if you anticipate any change from the routine.

• Practice stabilizing and cutting the skin on pieces of chicken at home. It is not the perfect model, but it can be helpful. Practice everything you can at home, including cutting, suturing, and tying. Operating room time is very valuable.

• Learn to be comfortable and relaxed in the operating room. As a surgeon, it is your home and workplace for a big part of your career.

Cutting tissue with scissors

Types of scissors

We will look at each of these characteristics briefly.

Blade design

Scissors blades are made as straight or curved (Figure 1-7). Most straight scissors are used for cutting sutures and bandages, and are sometimes called “suture scissors.” It is easier to cut a straight line with straight scissors than with curved scissors. Curved scissors are useful for tissue dissections. The curved angle of the blade lifts the tissue planes apart as the tip cuts the reflected tissue, which is placed on stretch. The curve of a scissors blade is easy to palpate through tissues. You will learn to protect tissues against the convex surface of the curve. An example of this technique is separating the levator aponeurosis from the underlying Müller’s muscle. As the two layers are pulled apart, fine tissue bands will be seen stretching between the tissue planes (learning to “pull” the layers apart is the most important surgical technical tip I can give you; more on this later). The convex surface of the scissors can slide up the fibrous bands and rest against the aponeurosis. Cutting can be performed without buttonholing the aponeurosis (Figure 1-8).

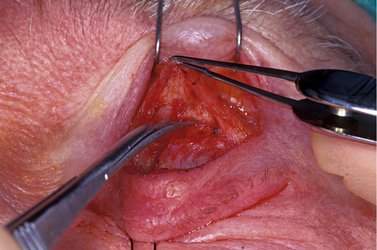

Figure 1-8 Dissection of levator aponeurosis from Müller’s muscle using curved Westcott scissors. Note how “pulling” the tissues apart creates bands of tissue that are easy to see and cut. The convex side of the scissors blades should be against the tissue that is the strongest, in this case the aponeurosis (see Figure 1-10, B).

Cutting motion

Most scissors close and open with opposite hand motions. These scissors are called iris scissors. You can control the force when opening the blades as well as the force when closing the blades with your hands. This allows you to use the scissors tips as a dissecting tool as you spread open the tissue planes by opening the scissors. Spring scissors open with the recoil of a spring mechanism in the handle of the scissors. Westcott scissors are an example of this type. These scissors are generally used for fine tissues where minimal hand motion is required (“finger tools”). The spring action determines the force of the opening of the blades, making these scissors somewhat more difficult to control and less useful for dissecting tissues with the opening of the blades.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree