Temple

BIOANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

The temple lies lateral to the eye and anterior to the ear. Its inferior border is defined by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone and its medial border is the zygoma itself, as it ascends lateral to the orbit. The superior border is defined by the subtle deflection from the concavity of the temporal fossa to the convexity of the frontal bone. There is great variability in the amount of non-hair-bearing skin anterior and inferior to the hairline (Fig. 13.1) and this factors into how operative wounds of the temple are repaired.

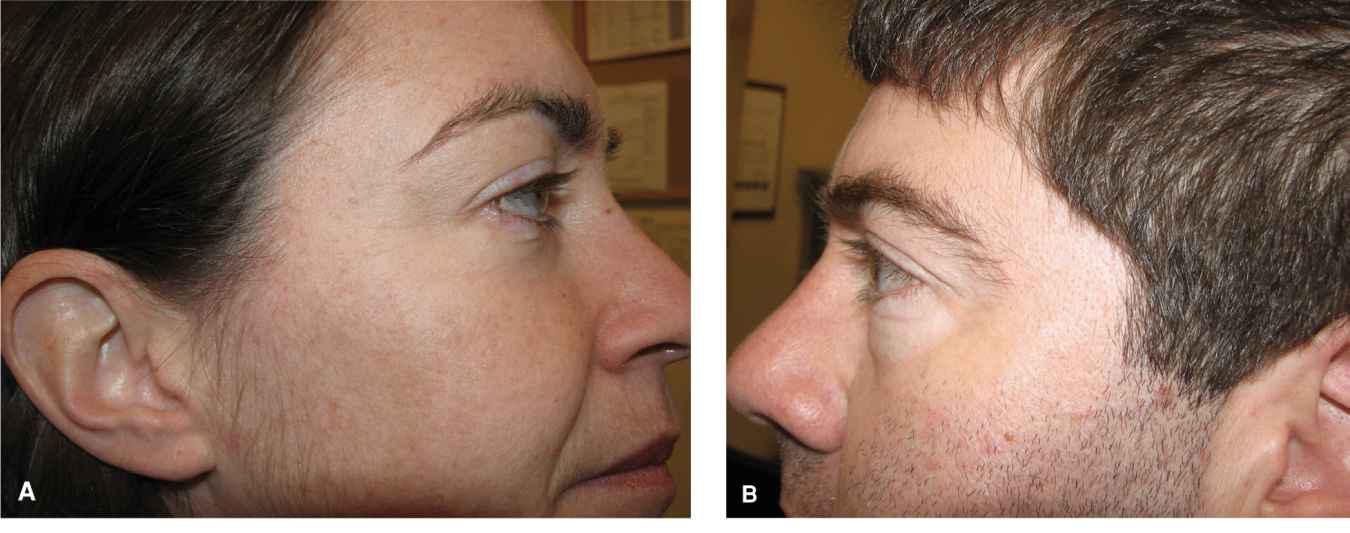

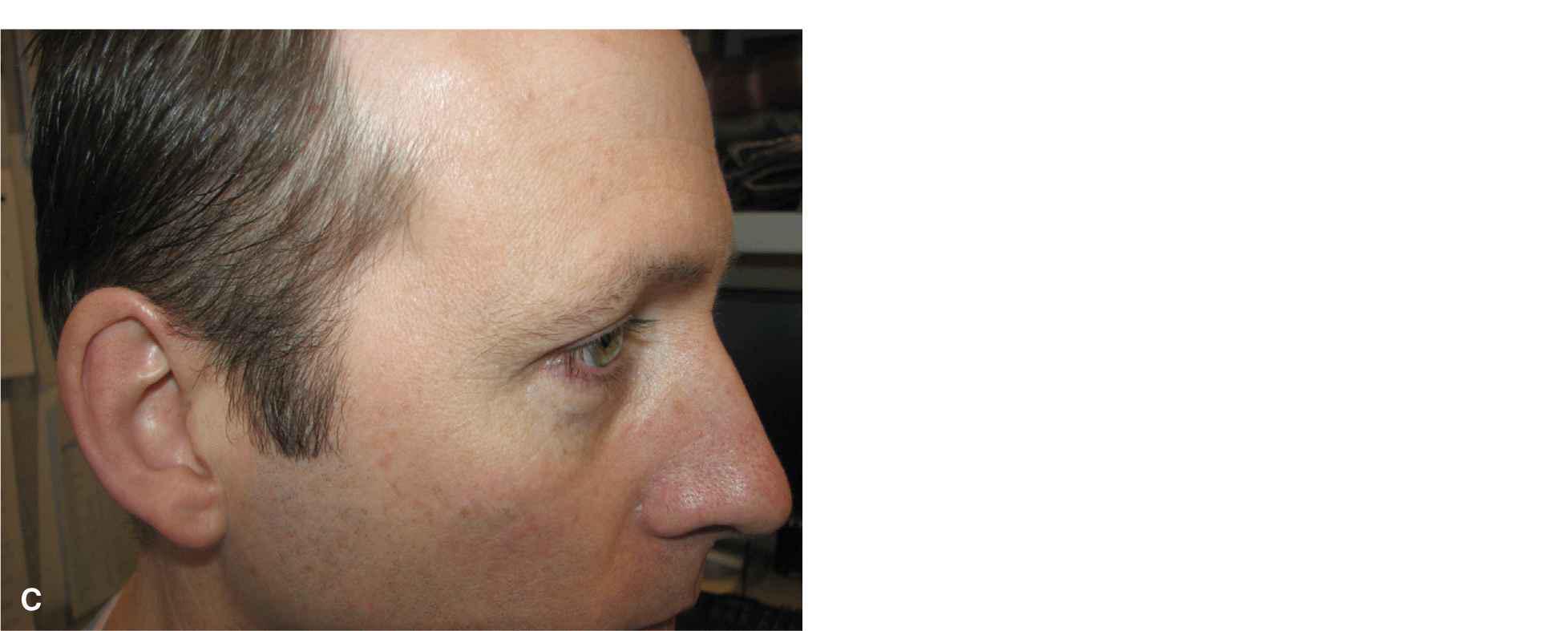

Figure 13.1 Variations in the anatomy of the temple. (A) Typical temple. There is a modest distance between the anterior hairline and the lateral brow. (B) Diminutive temple. The scalp/hairline extends anteriorly. (C) Broad temple. The hairline has receded and the area of non-hair-bearing skin is large

The temple has a predictable vascular supply from branches of the superficial temporal artery. These are large caliber vessels and run within the superficial fascia. They are readily identified and avoided at the time of surgery. If the main branches are transected at surgery, they should be ligated. The small perforators that emerge through the fascia also require meticulous hemostasis. In most patients, an easily identified and relatively avascular undermining plane exists just above the superficial fascia (Fig. 13.2). The main nerve of interest is the frontal branch of the temporal nerve. As reviewed extensively in Chapter 1, frontal branch of the temporal nerve is vulnerable in the superficial fascia from the zygomatic arch to the lateral forehead (Fig. 13.3).1 One sensory nerve of note is the auriculotemporal nerve that innervates the upper ear and runs just anterior to the ear at the lateral junction of the temple and cheek (Fig. 13.4). Trauma to the auriculotemporal nerve can lead to long-lasting numbness or neuralgia.

Figure 13.2 Undermining plane on the temple. This flap is elevated just above fascia. The superficial fascia envelopes and protects the branches of the temporal artery and the frontal branch of the facial nerve

Figure 13.3 The frontal branch of the facial nerve is identified and preserved during a repair

Figure 13.4 The auriculotemporal nerve and its anterior branch are shown. Trauma to this nerve is a frequent source of neuritic pain

In most individuals, the temple has a well-defined layer of adipose overlying the superficial temporal fascia, and the surface tissues usually enjoy substantial mobility, especially from the lower temple and cheek. Large flaps may be elevated just above fascia in a relatively bloodless tissue plane, and these flaps can be extended onto the cheek to recruit further laxity. Less motion is achieved from the forehead and scalp, where the tissues are more tightly bound. Deep to the superficial fascia and its accompanying neurovascular structures, lies the strong, sinewy temporalis fascia and temporalis muscle. The temporalis fascia may be used as an immobile anchor to provide support for a flap that is advanced from below.2

LINEAR REPAIRS

Most small and moderate wounds of the temple should be repaired linearly. The appropriate orientation of the repair is usually along a radial array away from the lateral canthus (Fig. 13.5).3 One advantage of a linear repair in this region is that in many individuals, a large portion of the reconstruction is hidden within the hairline. If the repair does extend into the hairline, it is often worthwhile to utilize a bevel-antibevel approach to avoid the transection of hairs and to facilitate closure (Fig. 13.6). If the medial origin of the repair is the lateral canthus, an S-shaped closure may assist with coursing over the zygomatic process in order to diminish the formation of tissue redundancies over this convexity.

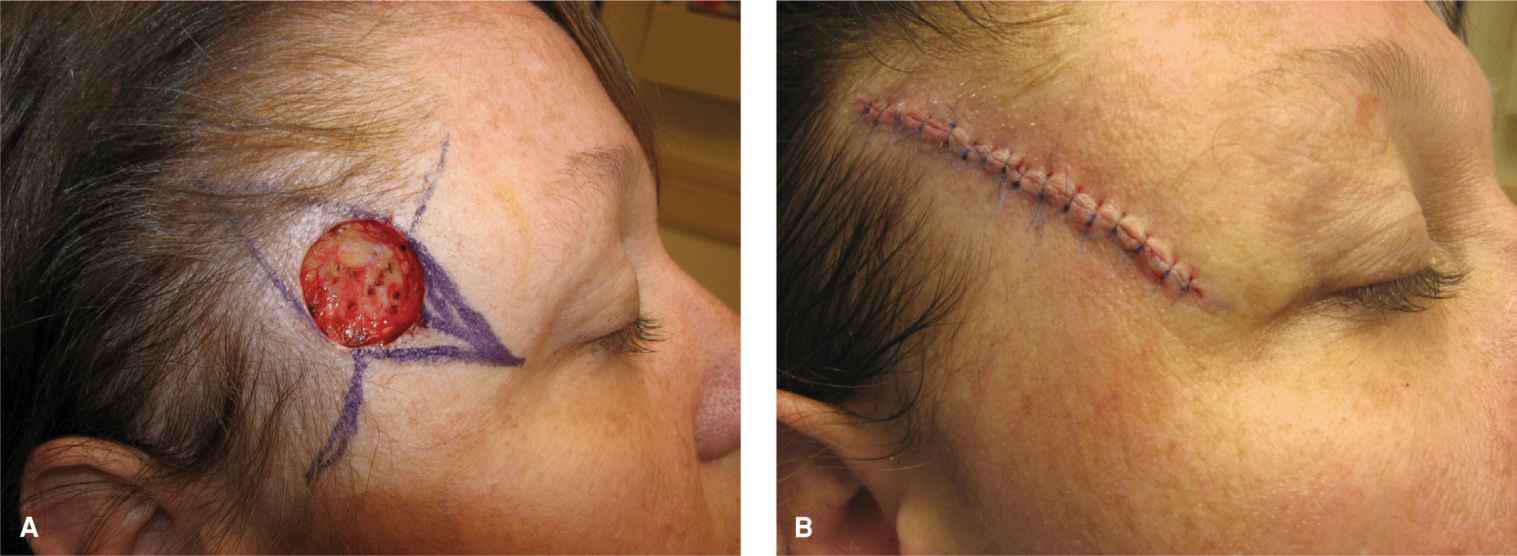

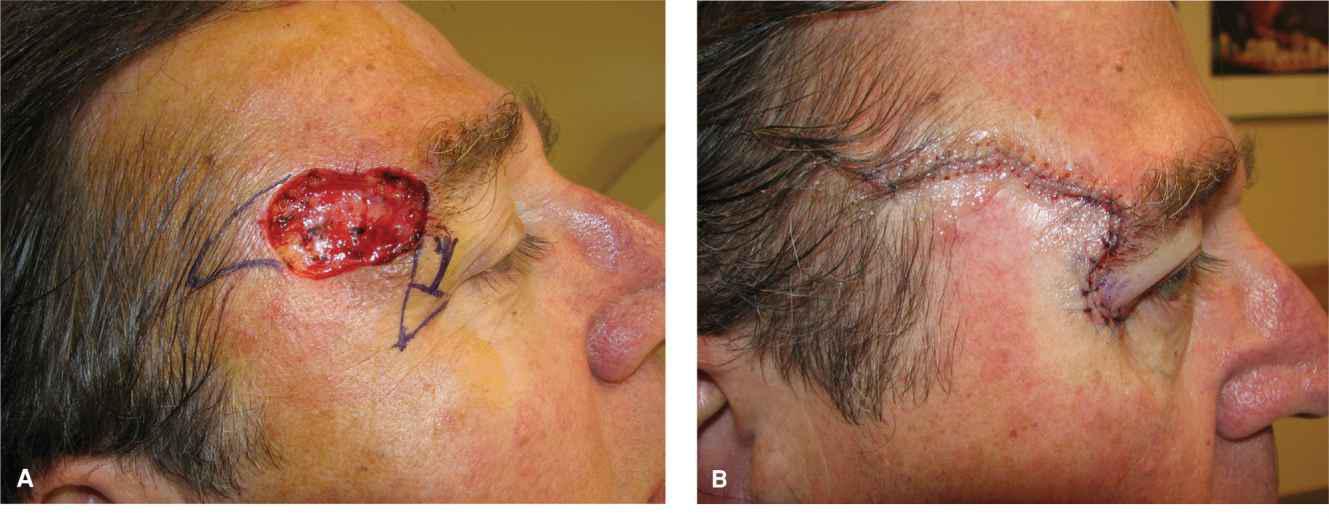

Figure 13.5 Linear repair on the temple. (A) A defect on the temple with a planned linear repair. The repair courses from superolateral to inferomedial along a radial array away from the lateral canthus. (B) The repair at closure

Figure 13.6 Bevel-antibevel closure on the temple. The upper portion of the wound is beveled outward and upward under the wound edge. The lower portion of the wound is beveled inward. The beveling accommodates the direction of hair growth and allows for more facile closure

Advancement

Advancement can be utilized on the temple to displace dog-ears and to hide scars. For wounds fairly high on the temple, a straight linear repair would course directly through the lateral brow. A flap that avoids the brow and instead removes the standing tissue cone further down on the zygoma with an apex at the lateral canthus is a more aesthetic closure. This displaces the medial dogear into the horizontal line extending out from the can-thus (Fig. 13.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree