Techniques and Principles in Plastic Surgery

Charles H. Thorne

Plastic surgery is the single most diverse specialty in the medical field, dealing with problems from the top of the head to the tip of the toes and with patients ranging in age from the newborn to nonagenarian. Plastic surgeons are the ultimate specialists but are also the modern day general practitioners, unrestricted by organ system, disease process, or patient age. Without an organ system of its own plastic surgery is based on principles rather than specific procedures in a defined anatomic location. Because of this freedom, whole subspecialties can be added to the field when new ideas, procedures, and techniques are developed. Since the previous edition less than a decade ago plastic surgery has enlarged significantly, adding, for example, vascularized composite allotransplantation (Chapter 06), fat grafting to the breast (Chapter 44), and a variety of perforator flaps to its armamentarium.

What is plastic surgery? No adequate definition exists. What is the common denominator between craniofacial surgery and hand surgery and between pressure sore surgery and cosmetic surgery? McCarthy from NYU defines it as the “problem-solving specialty.” A grandiose definition from a plastic surgery states: “Plastic surgery is surgery of the skin and its contents.” The phrase, plastic surgery, is derived from the Greek “Plastikos,” meaning to mold or to shape. While many plastic surgical procedures deal with reshaping, the majority do not, making even the title of the specialty somewhat misleading. No wonder the public has difficulty understanding what plastic surgery is!

No specialty receives the attention from the lay press that plastic surgery receives. At the same time, no specialty is less well understood. Although the public equates plastic surgery with cosmetic surgery, the roots of plastic surgery lie in its reconstructive heritage. Cosmetic surgery, an important component of plastic surgery, is but one piece of the plastic surgical puzzle.

Plastic surgery consists of reconstructive surgery and cosmetic surgery but the boundary between the two, like the boundary of plastic surgery itself, is difficult to draw. The more one studies the specialty, the more the distinction between cosmetic surgery and reconstructive surgery disappears. Even if one asks, as an insurance company does, about the functional importance of a particular procedure, the answer often hinges on the realization that the function of the face is to look like a face (i.e., function = appearance). A cleft lip is repaired so the child will look, and therefore hopefully function, like other children. A common procedure such as a breast reduction is enormously complex when one considers the issues of appearance, self-image, sexuality, and woman-hood, and defies categorization as simply cosmetic or necessarily reconstructive.

This chapter outlines basic plastic surgery principles and techniques that deal with the skin. Cross-references to specific chapters providing additional information are provided. Subsequent chapters in the first section will discuss other concepts and tools that allow plastic surgeons to tackle complex problems. Almost all wounds and all procedures involve the skin, even if it is only an incision, and therefore the cutaneous techniques described in this chapter are applicable to virtually every procedure performed by every specialty in surgery.

OBTAINING A FINE-LINE SCAR

“Will there be a scar?” Even the most intelligent patients ask this preposterous question. When a full-thickness injury occurs to the skin or an incision is made, there is always a scar. The question should be, “Will I have a relatively inconspicuous, fine-line scar?”

The final appearance of a scar is dependent on many factors, including the following: (a) Differences between individual patients that we do not yet understand and cannot predict; (b) the type of skin and location on the body; (c) the tension on the closure; (d) the direction of the wound; (e) other local and systemic conditions; and, lastly, (f) surgical technique.

The same incision or wound in two different patients will produce scars that differ in quality and aesthetics. Oily or pigmented skin produces, as a general rule, more unsightly scars (Chapter 2 discusses hypertrophic scars and keloids). Thin, wrinkled, pale, dry, “WASPy” skin of patients of English or Scotch-Irish descent usually results in less conspicuous scars. Rules are made to be broken, however, and an occasional patient will develop a scar that is not characteristic of his or her skin type.

Certain anatomic areas tend to produce unfavorable scars that remain hypertrophic or wide. The shoulder and sternal area are such examples. Conversely, eyelid incisions almost always heal with a fine-line scar.

Skin loses elasticity with age. Stretched-out skin, combined with changes in the subcutaneous tissue, produces wrinkling, which makes scars less obvious and less prone to widening in older individuals. Children, on the other hand, may heal faster but do not heal “better,” in that their scars tend to be red and wide when compared with scars of their grandparents. In addition, as body parts containing scars grow, the scars become proportionately larger. Beware the scar on the scalp of a small child!

Just as the recoil of healthy, elastic skin in children may lead to widening of a scar, tension on a closure bodes poorly for the eventual appearance of the scar. The scar associated with a simple elliptical excision of a mole on the back will

likely result in a much less appealing scar than an incisional wound. The body knows when it is missing tissue.

likely result in a much less appealing scar than an incisional wound. The body knows when it is missing tissue.

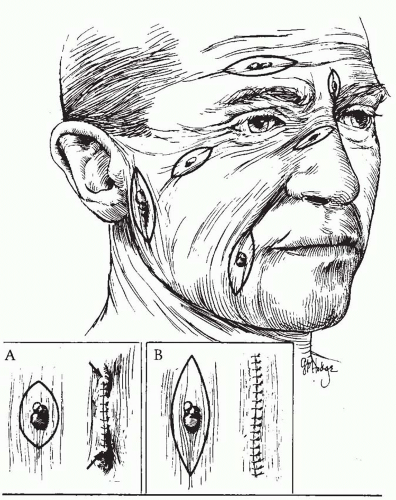

The direction of a laceration or excision also determines the eventual appearance of the scar. The lines of tension in the skin were first noted by Dupuytren. Langer also described the normal tension lines, which became known as “Langer lines.” Borges referred to skin lines as “relaxed skin tension lines” (Figure 1.1).

Elective incisions or the excision of lesions are planned when possible so that the final scars will be parallel to the relaxed skin tension lines. Maximal contraction occurs when a scar crosses the lines of minimal tension at a right angle. Wrinkle lines are generally the same as the relaxed skin tension lines and lie perpendicular to the long axis of the underlying muscles.

Other issues, which are not related to the scar itself but to perception, determine if a scar is noticeable. Incisions and scars can be “hidden” by placing them at the junction of aesthetic units (e.g., at the junction of the lip and cheek and along the nasolabial fold), where the eye expects a change in contour (Chapter xx). In contrast, an incision in the midcheek or midchin or tip of the nose will always be more conspicuous.

The shape of the wound also affects ultimate appearance. The “trapdoor” scar results from a curvilinear incision or laceration that, after healing and contracture, appears as a depressed groove with bulging skin on the inside of the curve. Attempts at “defatting” the bulging area are never as satisfactory as either the patient or surgeon would like.

Local conditions, such as crush injury of the skin adjacent to the wound, also affect the scar. So, too, will systemic conditions such as vascular disease or congenital conditions affecting elastin and/or wound healing. Nutritional status can affect wound healing, but usually only in the extreme of malnutrition or vitamin deficiency. Nutritional status is overemphasized as a factor in scar formation.

Technique is also overemphasized (by self-serving plastic surgeons) as a factor in determining whether a scar will be inconspicuous, but it is certainly of some importance. Minimizing damage to the skin edges with atraumatic technique, debridement of necrotic or foreign material, and a tension-free closure are the first steps in obtaining a fine-line scar. Ultimately, however, scar formation is unpredictable even with meticulous technique.

FIGURE 1.1. Relaxed skin tension lines. (Reproduced with permission from Ruberg R. L. In: Smith DJ, ed. Plastic Surgery, A Core Curriculum. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1994.) |

Two technical factors are of definite importance in increasing the likelihood of a “good” scar. First is the placement of sutures that are not excessively tight and are removed promptly so disfiguring “railroad tracks” do not occur. In other words, removing the sutures may be more important than placing them! Plastic surgeons have been known to mock other specialists for using heavy-gauge suture for skin closure, but the choice of sutures is irrelevant if the sutures are removed soon enough and if they have not been tied so tightly that they tear through the skin. Sutures on the face can usually be removed in 3 to 5 days and on the body in 7 days or less. Except for wounds over joints, sutures should rarely be left in for more than 1 week. A subcutaneous layer of closure and Steri-Strips are usually sufficient to prevent dehiscence.

The second important technical factor that may affect the appearance of scars is wound-edge eversion. While there is no evidence to support this statement, it is the author’s clinical experience that everted wound closures never look worse and often result in a less conspicuous scar than their non-everted counterparts. In wounds where the skin is brought precisely together, there is a tendency for the scar to widen. In wounds where the edges are everted, or even hyper-everted in an exaggerated fashion, this tendency may be reduced, possibly by reducing the tension on the closure. In other words, the ideal wound closure is not perfectly flat, but rather bulges with an obvious ridge, to allow for eventual spreading of that wound. Wound-edge eversion always goes away. The surgeon need not ever worry that a hyper-everted wound will remain that way.

CLOSURE OF SKIN WOUNDS

While the most common method of closing a wound is with sutures, there is nothing necessarily magic or superior about sutures. Staples, skin tapes, or wound adhesives are also useful in certain situations. Regardless of the method used, precise approximation of the skin edges without tension is essential to ensure primary healing with minimal scarring.

Wounds that are deeper than skin are closed in layers. The key is to eliminate dead space, to provide a strong enough closure to prevent dehiscence while wound healing is occurring, and to precisely approximate the skin edges without tension. Not all layers necessarily require separate closure. A closure over the calf, however, is subject to motion, dependence, and stretching with walking, requiring a stronger closure than the scalp, which does not move, is less dependent, and not subject to tension in daily activities. Placing deep absorbable sutures is not always desirable. The author tends to use only Nylon skin sutures without any deeper sutures when approximating pediatric facial lacerations because of an impression that there is less inflammation and erythema and certainly less chance of suture abscess.

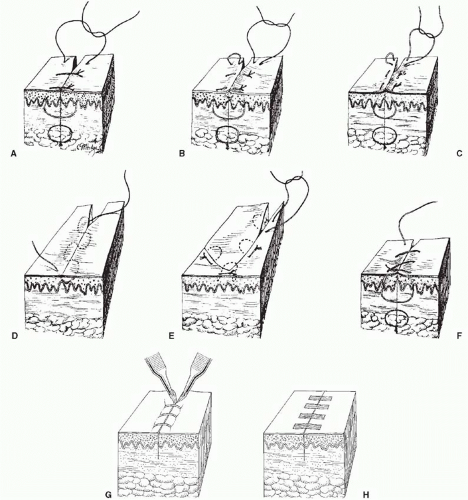

Except for dermal sutures, which are placed with the knot buried to prevent it from emerging from the skin during the healing process, sutures should be placed with the knot superficial to the loop of the suture (not buried), so that the tissue layers can be everted (Figure 1.2A).

Buried dermal sutures provide strength so the external sutures can be removed early, but do not prevent the scar from spreading over time. There is no technique, even the technique of eversion described above, that reliably prevents a wound that has an inclination to widen from doing so.

Suturing Techniques

Techniques for suturing are illustrated in Figure 1.2 and are listed below.

Simple Interrupted Suture.

The simple interrupted suture is the gold standard and the most commonly employed suture. The needle is introduced into the skin at an angle that allows it to pass into the deep dermis at a point further removed from the wound edge. This allows the width of suture at its base in the dermis to be wider than the epidermal entrance and exit points, giving the suture a triangular appearance when viewed in cross section. It also everts the skin edges. Care must be taken to ensure that the suture is placed at the same depth on each side of the incision or wound, otherwise the edges will overlap. Sutures are usually placed approximately 5 to 7 mm apart and 1 to 2 mm from the skin edge, although the location and size of the needle and caliber of the suture material make this somewhat variable.

Vertical Mattress Suture.

Vertical mattress sutures may be used when eversion of the skin edges is desired and cannot be accomplished with simple sutures alone. Vertical mattress sutures tend to leave the most obvious and unsightly cross-hatching if not removed early.

Horizontal Mattress Suture.

Horizontal mattress sutures have been much maligned but are the author’s favorite suture for reliable skin edge approximation and eversion. They are particularly advantageous in thick glabrous skin (feet and hand). In the author’s opinion, horizontal mattress sutures are far superior to their vertical counterparts.

Subcuticular Suture.

Subcuticular (or intradermal) sutures can be interrupted or placed in a running fashion. In a running subcutaneous closure, the needle is passed horizontally through the superficial dermis, parallel to the skin surface, to provide close approximation of the skin edges. Care is taken to ensure that the sutures are placed at the same level. Such a technique obviates the need for external skin sutures and circumvents the possibility of suture marks in the skin.

Absorbable or nonabsorbable suture can be used, with the latter to be removed at 1 to 2 weeks after suturing.

Absorbable or nonabsorbable suture can be used, with the latter to be removed at 1 to 2 weeks after suturing.

Half-Buried Horizontal Mattress Suture.

Half-buried horizontal mattress sutures are used when it is desirable to have the knots on one side of the suture line with no suture marks on the other side. For example, when insetting the areola in breast reduction, this method leaves the suture marks on the dark, pebbly areola instead of on the breast skin.

Continuous Over-and-Over Suture.

Continuous over-and-over sutures, otherwise known as running simple sutures, can be placed rapidly but depend on the wound edges being more or less approximated beforehand. A continuous suture is not nearly as precise as interrupted sutures and the author almost never uses them on the face. Continuous sutures can also be placed in a locking fashion to provide hemostasis by compression of wound edges. They are especially useful in scalp closures.

Skin Staples.

Skin staples are particularly useful as a time-saver for long incisions or to position a skin closure or flap temporarily before suturing. Grasping the wound edges with forceps to evert the tissue is helpful when placing the staples to prevent inverted skin edges. Staples must be removed early to prevent skin marks and are ideal for the hair-bearing scalp.

Skin Tapes.

Skin tapes can effectively approximate the wound edges, although buried sutures are often required in addition to skin tape to approximate deeper layers, relieve tension, and prevent inversion of the wound edges. Skin tapes can also be used after skin sutures are removed to provide added strength to the closure.

Skin Adhesives.

Skin adhesives have been developed and may have a role in wound closure, especially in areas where there is no tension on the closure, or where strength of closure has been provided by a layer of buried dermal sutures. Adhesives, by themselves, however, do not evert the wound edges. Eversion must be provided by deeper sutures.

Methods of Excision

Lesions of the skin can be excised with elliptical, wedge, circular, or serial excision.

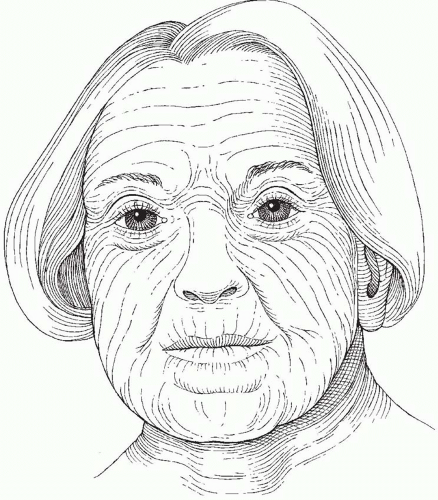

Elliptical Excision.

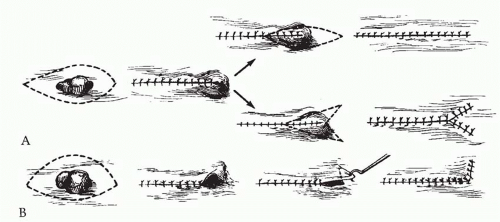

Simple elliptical excision is the most commonly used technique (Figure 1.3). Elliptical excision of inadequate length may yield “dog-ears,” which consist of excess skin and subcutaneous fat at the ends of a closure. There are several ways to correct a dog-ear, some of which are shown in Figure 1.4. Dog-ears are the bane of plastic surgical existence and one must be facile with their elimination. Dogears do not disappear on their own.

Wedge Excision.

Lesions located at or adjacent to free margins can be excised by wedge excision. In some elderly patients, one third of the lower lip and one fourth of the upper lip can be excised with primary closure (Figure 1.5).

Circular Excision.

When preservation of skin is desired (such as the tip of the nose) or the length of the scar must be kept to a minimum (children), circular excision might be desirable. Figure 1.6 shows some closure techniques. Figure 1.6 is included because these techniques may be of value, as well as for historical purposes. Circular defects can also be closed with a purse-string suture that causes significant bunching of the skin. This is allowed to mature for many months and may result in a shorter scar on, for example, the face of a child.

FIGURE 1.4. Three methods of removing a dog-ear caused by making the elliptical excision too short. A. Dog-ear excised, making the incision longer, or converted to a “Y.” B. One method of removing a dog-ear caused by designing an elliptical excision with one side longer than the other. Conversion to an “L” effectively lengthens the shorter side.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|