The authors discuss how, in performing an endoscopic brow lift, meticulous surgical technique, adherence to anatomic dissection planes, and direct visualization used at key points in the procedure enable a safer, more-complete dissection and a better outcome. Anatomy as it relates to the procedure is discussed. Patient evaluation and patient expectations are reviewed with a discussion of the points to present to patients about outcomes of this surgery. Detailed steps of the endoscopic brow-lift technique are presented. Complications are discussed and the authors conclude with a summarization of what the ideal brow-lift procedure would accomplish.

Key points

- •

The goal of endoscopic brow lifting is stabilization of the brow at an aesthetically ideal height and orientation.

- •

The procedure results in reliable and reproducible surgical outcomes.

- •

A full understanding of the surgical anatomy, especially in the temporal dissection pockets, will help to prevent complications and optimize results.

- •

An understanding of brow aesthetics is necessary before beginning this procedure.

- •

There is debate as to the best method of brow fixation.

- •

A thorough understanding of the endoscopic brow-lift equipment enables a safe, efficient, and effective procedure.

Introduction

The breadth of human emotion is conveyed through our eyes; thus, the eyes must play a fundamental role in aesthetic surgery of the face. During the aging process, there is a gradual loss of tissue elasticity and forehead rhytids become more prominent. Descent of the brow may ensue and, in time, may contribute to lateral upper eyelid hooding and visual field deficits. This brow ptosis and lateral hooding may be misconstrued as fatigue, tiredness, and lethargy, despite good rest, energy, and health. An endoscopic brow lift, often in conjunction with blepharoplasty, rhytidectomy, and volume replacement, aims to restore a more youthful and rested appearance. (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.)

The goals of any brow-lifting procedure are to stabilize the brow at an aesthetically ideal height and orientation and provide reproducible and lasting results while concealing scars and avoiding the stigmata of a facial plastic surgery: hairline elevation, overelevated brows, or a quizzical appearance. (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.) The authors emphasize the concept of brow stabilization instead of brow elevation . Rather than raising the eyebrows, the goal is to fixate the brows to minimize progressive brow ptosis. These goals were the impetus for developing the endoscopic brow-lift technique.

Since first being described by Isse in 1992, the endoscopic brow lift has become a technique capable of producing reliable and lasting brow restoration. This approach allows for correction of both brow ptosis and glabellar rhytids. As the authors discuss, meticulous surgical technique, adherence to anatomic dissection planes, and direct visualization used at key points in the procedure enables a safer, more-complete dissection and ultimately a better outcome.

Introduction

The breadth of human emotion is conveyed through our eyes; thus, the eyes must play a fundamental role in aesthetic surgery of the face. During the aging process, there is a gradual loss of tissue elasticity and forehead rhytids become more prominent. Descent of the brow may ensue and, in time, may contribute to lateral upper eyelid hooding and visual field deficits. This brow ptosis and lateral hooding may be misconstrued as fatigue, tiredness, and lethargy, despite good rest, energy, and health. An endoscopic brow lift, often in conjunction with blepharoplasty, rhytidectomy, and volume replacement, aims to restore a more youthful and rested appearance. (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.)

The goals of any brow-lifting procedure are to stabilize the brow at an aesthetically ideal height and orientation and provide reproducible and lasting results while concealing scars and avoiding the stigmata of a facial plastic surgery: hairline elevation, overelevated brows, or a quizzical appearance. (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.) The authors emphasize the concept of brow stabilization instead of brow elevation . Rather than raising the eyebrows, the goal is to fixate the brows to minimize progressive brow ptosis. These goals were the impetus for developing the endoscopic brow-lift technique.

Since first being described by Isse in 1992, the endoscopic brow lift has become a technique capable of producing reliable and lasting brow restoration. This approach allows for correction of both brow ptosis and glabellar rhytids. As the authors discuss, meticulous surgical technique, adherence to anatomic dissection planes, and direct visualization used at key points in the procedure enables a safer, more-complete dissection and ultimately a better outcome.

Anatomy

The ability to limit morbidity is the primary advantage of the endoscopic technique over more traditional coronal approaches. A detailed understanding of forehead, scalp, and temporal anatomy serves as the basis for a safe, efficient, and successful endoscopic procedure.

It is generally accepted that the supraorbital ridge separates the forehead and the midface, whereas the hairline separates the forehead from the scalp. It is effective to discuss the brow, forehead, and scalp anatomy in respect to layers. This region is commonly divided into 5 layers:

- 1.

Skin

- 2.

Subcutaneous tissue

- 3.

Aponeurosis (galea)

- 4.

Loose areolar tissue

- 5.

Pericranium

A layer of thick skin overlies and is fixed to the subcutaneous tissue by fibrous septa traversing from the skin to the galea aponeurosis. The galea aponeurosis lies deep to the subcutaneous tissue and is a fibrous fascial layer that connects the frontalis and occipitalis muscles. It represents the continuation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) layer of the forehead and scalp. The galea sits on top of loose areolar tissue, which separates the galea from the pericranium, and provides for relatively free movement of the galea over the pericranial layer. The pericranium densely adheres to the skull.

Brow Muscles

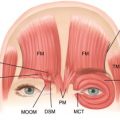

The brow musculature consists of the frontalis, procerus, and the paired corrugator muscles. Each of these muscles independently contributes to brow positioning, lateral eyelid hooding, and forehead/glabellar rhytids. In the discussion of brow lifting, it is useful to classify these muscles into brow elevators and brow depressors. The frontalis muscle is the primary brow elevator and is responsible for deep horizontal brow rhytids. It originates from the galea and inserts into the dermis via fibrous septa. The main depressors of the brow include the procerus muscle, the paired corrugator supercilii, and the paired orbicularis oculi musculature. The procerus originates from the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages and inserts into the caudal border of the frontalis muscle. The contraction of this muscle results in the horizontal rhytids in the glabella region. The paired corrugator supercilii muscles originate from the nasal process of the frontal bone and attach in an interdigitating fashion to the frontalis and orbicularis oculi muscles. The contraction of the corrugators will medialize and depress the brow, thus creating vertical glabellar furrows. The orbicularis oculi serves the important role of palpebral sphincter and is a rather minor depressor of the brow ( Fig. 1 ).

Brow Innervation

The temporal branch of the facial nerves provides motor innervation to the brow musculature and the superior portion of the orbicularis oculi muscle. The nerve leaves the parotid gland deep to the SMAS and crosses the zygomatic arch over the middle third, traveling between the SMAS and periosteum. As the nerve travels above the zygomatic arch, it travels within the temporoparietal fascia (TPF) until inserting into the undersurface of the musculature. The muscular insertion point is on average 1 cm above the supraorbital rim. The course of the nerve can be approximated by drawing a line spanning a point 0.5 cm anterior to the tragus and 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral taper of the brow.

Afferent branches of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, via the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, are responsible for sensation to the forehead and brow. It should be noted that after emerging from the supraorbital notch, the nerve travels in a supramuscular plane on the surface of the frontalis muscle. The lacrimal nerve supplies lateral brow innervation.

The forehead and brow enjoy a robust arterial blood supply from the internal and external carotid systems. The internal carotid terminally branches into the ophthalmic artery, which then branches distally into the supraorbital and supratrochlear arteries to provide for the central forehead and scalp. The external carotid terminally branches into the superficial temporal artery, which, through arborization, provides for the lateral forehead. The zygomaticotemporal artery branches off the superficial temporal artery to provide for the lateral brow.

The zygomaticotemporal venous drainage that receives branches bridging the surgical plane between the superficial temporal fascia and deep temporal fascia (DTF) deserves special mention. A large perforating vein in this system has been named the sentinel vein because it has been found to predictably fall within 2 mm of the temporal branch of the facial nerve. This vein is located approximately 1 cm lateral to the frontozygomatic suture line. Importantly, when more than one bridging vessel is encountered during the dissection, there is often a corresponding temporal branch of the facial nerve in proximity. These vessels are located in close proximity and serve as a topographic marker for the frontal branch of the frontal nerve during endoscopic dissection.

Of critical importance to endoscopic brow lifting is a comprehensive understanding of the fascial planes of the scalp, forehead, brow, and temporal regions. The SMAS envelops the mimetic musculature of the lower and midface. As the SMAS extends above the zygomatic arch, it becomes continuous with the TPF. Superiorly, in the region of the brow and scalp, the TPF/SMAS is in continuity with the galea aponeurosis. In the temporal region, the DTF lies beneath the TPF. The DTF envelops the temporalis muscle, thus splitting into a deep and superficial layer ( Fig. 2 ). The superficial layer of the DTF and the deep layer of the DTF form a confluence with the frontoparietal periosteum to form the temporal line. The DTF and the lateral extent of the galea also fuse with the lateral orbital rim and medial zygomatic arch periosteum to form the conjoined tendon. The fusion of the galea and frontal periosteum at the supraorbital rim creates the arcus marginalis, which serves to anchor the brow and represents the peripheral attachment of the orbital septum and, thus, will limit ones ability to achieve brow mobilization if not completely released.

Evaluation

An accurate evaluation of the upper face and brow necessitates a thorough understanding of forehead and brow aesthetics. The aesthetically ideal upper brow remains a source of debate. In women, the youthful brow should be arched and lie just above the supraorbital rim. In men, however, the youthful brow position and contour is flatter without the high-arching lateral component and should sit at or near the supraorbital rim. It is generally accepted that in women, the brow should arch with an apex in line with the lateral limbus or the lateral canthus. The lateral brow should approximate an oblique line drawn from the nasal ala through the lateral canthus. A line vertically tangent to the lateral nasal ala should approximate the medial extent of the brow ( Fig. 3 ). (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.)

Patient Expectations

As with any cosmetic surgical procedure, the patients’ motivation and expectations for surgery must be understood. A thorough ophthalmologic history, including risk factors of bleeding diathesis or prior ophthalmologic trauma, should be elicited. A history of dry eyes or previous blepharoplasty must also be identified because of an increased risk for lagophthalmos in this patient population. (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.)

Overview Facial Assessment

The assessment proceeds with an overview of the face, brow, and eyes. Facial or brow asymmetries, eyelid ptosis, and lid laxity must be identified because they will influence surgical planning. The hairline is documented using the Norwood classification. Prominent frontal bossing has implications for an endoscopic brow-lift procedure and should be noted. Next, the relationship of the eyebrow to the supraorbital rim is evaluated.

The ideal patient for an endoscopic brow lift has been described as having medium to thin skin thickness, prominent glabellar rhytids, and relatively mild brow ptosis with minimal skin redundancy.

Eyebrow volume also can be inspected. Despite the observation of volume wasting in the midface with the aging process, and orbital hollowing, the eyebrow volume may not actually decrease with age. The combined effect of a stable eyebrow volume and orbital hollowing is an accentuated impact of light reflections and shadows, creating a false impression of eyebrow ptosis.

Identifying Relative Contraindications to Endoscopic Brow Lift

Relative contraindications exist for women with high hairlines, men with male pattern baldness, patients with thick adherent skin, and patients with extensive bone attachments. In patients with male pattern baldness, difficulty can arise in attempting to place the access incisions posterior to the receding hairline. In this setting, the calvarium may prevent endoscopic visualization over the horizon. However, in the senior author’s experience, with meticulous wound closure, the endoscopic brow-lift incisions heal with minimal visibility even in a non–hair-bearing scalp.

Patient Photographs

Lastly, preoperative photographs are obtained. Standardized photographic views are important for preoperative and postoperative assessments. They should include a 5-view head series, along with close-up views of the eyes (closed/open/upward gaze/lateral gaze). (Terella AM, Wang TD. Debate on current topics in facial plastic surgery: upper face rejuvenation. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America . Submitted for publication, October, 2011.)

Patient perspective

As with all facial plastic surgery, a successful outcome begins with a good rapport between patients and the surgeon. Both the patients and surgeon must share an understanding of the motivation for seeking this cosmetic change and must share realistic expectations.

In the authors’ opinion, it is important for patients to develop an understanding of aging face physiology. Specifically, the authors discuss that, in the aging face, there is a loss of skin elasticity, decreased bulk of subcutaneous tissue, and increased skull bone resorption. Further, there is an inherent imbalance between the brow elevators and brow depressors, favoring the depressors in the lateral brow. Together these factors contribute to the development of forehead and eyebrow ptosis, most notably in the lateral eyebrow. Emphasis is placed on illustrating that the upper eyelid may be affected by the eyebrow position. The lateral descent of the brow adds significant fullness and redundancy to the upper lateral eyelid. Empowering patients with this understanding helps to guide expectations and facilitates an appreciation of the utility of endoscopic brow lifting.

In discussing the specifics of the endoscopic brow-lift procedure, there has been an evolution in the authors’ conceptualization of the lifting component of the procedure. As mentioned previously, the authors now approach the technique as a stabilization of the brow more so than a lifting procedure. As such, the procedure is described to patients as one to effectively resist the unopposed pull of the lateral brow depressors and minimize the continued descent of the brow. This consideration is of great importance for male patients in whom avoiding overelevation is critical.

Realistic expectations to provide patients include

- 1.

Effective restoration and stabilization of the brow at a more youthful and aesthetically pleasing height

- 2.

Resolution of brow ptosis

- 3.

Improved lateral eyelid hooding caused by brow ptosis

- 4.

Improved forehead and glabellar rhytids

Patients should seem more rested and revitalized. Their eyes should seem brighter and less tired. The authors emphasize that the changes are permanent but that the aging process will continue to occur. In this sense, the upper face will always seem more rejuvenated than if the brow lift had never been completed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree