20 Surgical Treatment of Rectocele and Perineal Defects

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The terminology of the anatomic tissue that is present under the vaginal epithelium has been the subject of debate for most of the past century. The term fascia was introduced by Emmet in 1883. The histology of the apical portion of the posterior vaginal wall consists of mucosa (which includes the epithelium of the posterior wall and the lamina propria), a superficial and deep muscularis layer, and adventitia. This fibromuscularis has been named rectovaginal fascia and perirectal fascia, perhaps giving the surgeon an illusion of sturdier tissue than is actually present. Comparisons of the histology of women with and without prolapse have shown that the smooth muscle content of the posterior vaginal wall of women with prolapse is disorganized and significantly reduced in comparison to women without prolapse.

Prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall may be secondary to the presence of an enterocele, sigmoidocele, or rectocele, or a combination of these entities. A rectocele is an anterior protrusion of the rectal wall to the posterior vaginal wall. The rectovaginal space exists between the vaginal tube and the rectum. This potential space, occupied by areolar tissue, allows the vagina and rectum to function independently of each other. Support of the posterior vaginal wall is provided by a complex interaction of the integrity of the vaginal tube, the connective tissue support, and muscular support of the pelvic floor. DeLancey (1996) divided the connective tissue support of the vagina into three levels. All three levels of support should be evaluated and addressed during surgical management of the posterior vaginal wall.

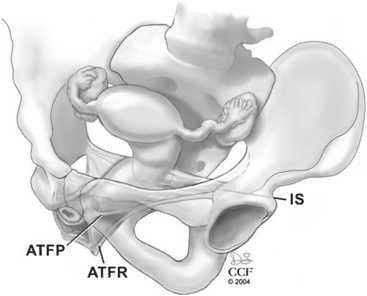

Level II includes the support for the middle half of the vagina. This support is provided by the endopelvic fascia attaching the lateral posterior vaginal wall to the aponeurosis of the levator ani on the pelvic sidewall. Most of the fibers of the endopelvic fascia connect the lateral edge of the vaginal tube to the pelvic sidewall. Very few of the fibers actually run like a sheet from sidewall to sidewall. This lateral attachment, the arcus tendineus fasciae rectovaginalis, is dorsal to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis for the distal half of the posterior wall (Fig. 20-1). The sidewall attachment of the posterior vaginal wall converges with the sidewall attachment of the anterior wall approximately midway in the vaginal canal. The proximal half of the posterior vagina is supported by bilateral endopelvic attachments to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis.

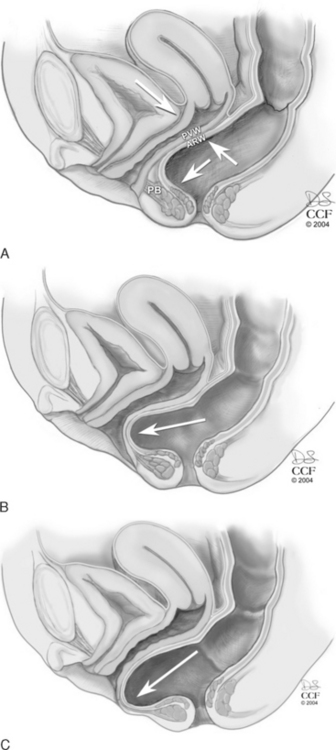

The levator hiatus has been shown to be larger in women with prolapse than in those with normal support. In a woman with an intact pelvic floor, the puborectalis is in a chronic state of contraction. This contraction closes the vaginal canal, and the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are in direct apposition. With defecation, the increased pressure placed on the posterior vaginal wall is equilibrated by the opposing anterior vaginal wall, and minimal stress is placed on the endopelvic fascial attachments (Fig. 20-2, A). If there is muscular and/or neurologic damage to the puborectalis, the levator hiatus widens and the vaginal canal opens. The increased rectal pressure and distension associated with defecation places strain on the endopelvic fascial attachments and the fibromuscularis of the posterior vaginal wall and can result in rectocele and perineal descent (Fig. 20-2, B,C).

Chronic strain and constipation have been associated with (but do not necessarily cause) rectocele, perineal descent, and fecal incontinence. With chronic straining, a stretch is placed in the pudendal nerve and the nerve to the levator ani muscle. Meschia et al. (2002) found that fecal incontinence was more prevalent in women with a rectocele that extended beyond the hymen (31%) than in women with prolapse inside the hymenal ring (19%). Increasing body mass index has been strongly associated with incident rectocele but not with prolapse of other areas of the vagina (cystocele or uterine prolapse).

EVALUATION

History

Many women with a rectocele or a perineal body defect are asymptomatic. However, women may complain of symptoms associated with prolapse, such as bulging of the vagina and pressure, which worsens by the end of the day and improves when lying down. Sexual dysfunction also occurs in some women with prolapse. A woman may reduce sexual activity due to the discomfort of the prolapse or the embarrassment of the urinary or anal incontinence, which may accompany her prolapse. A woman with a perineal body defect, which leads to a widened genital hiatus, may describe loss of sensation for herself and her partner during intercourse.

Physical Examination

To stage the severity of prolapse the posterior vaginal wall is visualized with the posterior blade of a bivalve speculum or a Sims speculum. The retractor elevates the anterior wall and reduces any uterine or apical prolapse. The patient is asked to increase abdominal pressure with a Valsalva maneuver or cough. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system is a standardized, validated tool for measuring and staging pelvic organ prolapse (see Chapter 5). Measurements of the posterior vaginal wall are documented at maximal strain, 3 cm proximal to the hymen (Ap), at the most dependent portion of the posterior vaginal wall proximal to this mark (Bp), and at the vaginal cuff (C) or cul-de-sac, if the uterus is present (D). The genital hiatus (GH) and perineal body (PB) are measured with the patient straining. Evaluation for and staging of concurrent anterior wall and apical prolapse should be performed.

The perineal body should be evaluated for descent. It may be difficult to measure perineal descent, but documentation of its presence or absence can be helpful in planning your surgery. Descent of the perineal body occurs with a lack of continuity from the suspensory support at the apex (level I) to the perineal body (level III). It may also occur because of a mass effect of the rectum or small bowel herniating into the perineal body, a perineocele. Perineal descent has also been associated with fecal incontinence. Nerve stretch and subsequent neuromuscular damage is one of the proposed mechanisms of fecal incontinence.

A focused neurologic examination includes evaluation of sensation, motor function, and reflexes of sacral nerves 2–4. The patient is asked to discriminate between sharp and dull on the perineum. Assess pelvic floor muscle strength with the patient contracting and relaxing the pelvic floor muscles around the examiner’s fingers. Reflex testing includes the bulbocavernosus reflex and anal wink (see Chapters 6 and 11.

Diagnostic Tests

Rectoceles that retrain contrast tend to be larger than those that do not. However, fluoroscopic evidence of barium trapping does not relate to patient symptoms. In the symptomatic, elderly population, Savoye-Collet et al. (2003) found no association between the abnormalities demonstrated by defecography and symptoms. Defecography performed following surgical management of rectoceles has generally shown a reduction in the size of the rectocele and improvement in emptying. The limitations of defecography include that it requires special equipment, exposes the patient to radiation, does not show the rectum and adjacent soft tissue structures simultaneously, and is uncomfortable and poorly accepted by patients.

At this time, there is a lack of a standardized method of establishing a radiologic diagnosis of rectocele. Clinical examination has good sensitivity for the detection of a rectocele; therefore, radiologic confirmation of the presence or absence of a rectocele is not worthwhile. Although defecatory dysfunction is common in women with prolapse, the extent of the prolapse does not necessarily correlate with the extent of bowel symptoms. If the woman’s primary complaint is defecatory dysfunction or fecal incontinence and not a bulge, surgical correction of the rectocele or perineal body defect may not correct her symptoms. Ancillary testing is then pursued based on the woman’s complaints. Validated functional and quality-of-life questionnaires are now available. These may be performed preoperatively and postoperatively to provide a standardized method of evaluating the surgical outcomes. The patient’s preoperative symptoms and surgical goals will guide the provider in the selection of additional testing.

A woman who describes lifelong infrequent bowel movements (less than one per week) and an absence of a daily urge to defecate is unlikely to be cured of her constipation with a rectocele repair. A colon transit study may be helpful in identifying patients with slow-transit constipation. Dietary modifications, including fiber and laxatives, should be encouraged in any woman whose main complaint is constipation (see Chapter 25).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree