21 Surgical management of migraine headaches

Synopsis

Approximately 30 million Americans suffer from migraine headaches (MH) and lifetime prevalence is estimated to be 11–32%, including 18% of women and 6% of men.

Approximately 30 million Americans suffer from migraine headaches (MH) and lifetime prevalence is estimated to be 11–32%, including 18% of women and 6% of men.

Poorly controlled or uncontrolled MH can be treated surgically.

Poorly controlled or uncontrolled MH can be treated surgically.

Before considering a patient for surgical management, he/she should be evaluated by a neurologist for diagnosis and medical management.

Before considering a patient for surgical management, he/she should be evaluated by a neurologist for diagnosis and medical management.

In the surgical evaluation of patients with MH, the trigger site can be confirmed by botulinum toxin A (BTX-A) injection or nerve block. If the history or computed tomography (CT) scan findings are strongly indicative of a specific trigger site, this step can be bypassed.

In the surgical evaluation of patients with MH, the trigger site can be confirmed by botulinum toxin A (BTX-A) injection or nerve block. If the history or computed tomography (CT) scan findings are strongly indicative of a specific trigger site, this step can be bypassed.

The four major trigger sites are: frontal, temporal, occipital, and nasal.

The four major trigger sites are: frontal, temporal, occipital, and nasal.

In the frontal trigger site, the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves are irritated while passing through the frowning muscles and this area is treated by resection of the glabellar muscle group (depressor supercilii, corrugator supercilii, and lateral portion of the procerus muscle) and replacement with fat graft.

In the frontal trigger site, the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves are irritated while passing through the frowning muscles and this area is treated by resection of the glabellar muscle group (depressor supercilii, corrugator supercilii, and lateral portion of the procerus muscle) and replacement with fat graft.

The temporal trigger site is treated by avulsion of the zygomaticotemporal branch of trigeminal nerve (ZTBTN) as it emerges from deep temporal fascia.

The temporal trigger site is treated by avulsion of the zygomaticotemporal branch of trigeminal nerve (ZTBTN) as it emerges from deep temporal fascia.

The occipital trigger site is located in the posterior part of the neck where the greater occipital nerve is passing through the semispinalis capitis muscle and crosses over the occipital artery; treatment includes partial resection of the muscle, padding the nerve with a subcutaneous flap, and resection of the artery adjacent to the nerve.

The occipital trigger site is located in the posterior part of the neck where the greater occipital nerve is passing through the semispinalis capitis muscle and crosses over the occipital artery; treatment includes partial resection of the muscle, padding the nerve with a subcutaneous flap, and resection of the artery adjacent to the nerve.

Rhinogenic trigger site is treated with septoplasty, elimination of contact points between the turbinate and the septum, reduction of enlarged turbinates, and decompression of concha bullosa or septa bullosa.

Rhinogenic trigger site is treated with septoplasty, elimination of contact points between the turbinate and the septum, reduction of enlarged turbinates, and decompression of concha bullosa or septa bullosa.

Introduction

Headaches are the seventh leading presenting complaint in ambulatory medical care in the US.1 Nearly 30 million Americans suffer from MH and lifetime prevalence is estimated to be 11–32% across several countries. Eighteen percent of women and 6% of men are involved, and two-thirds of these patients do not benefit from over-the-counter medications. In women, MHs are more common than asthma (5%) and diabetes (6%) combined. MHs are ranked as number 19 among all diseases worldwide causing disability. Many of the available prophylactic medications harbor side-effects such as sedation, paresthesia, weight gain, cognitive impairment, and sexual dysfunction. The cost of migraine treatment and loss of time from work associated with MH impose a major economic burden on the patient and society, collectively exceeding $13 billion.1–11

Basic science/disease process

The diagnostic criteria of MH are shown in Box 21.1. There are two subtypes of migraine: migraine with aura and migraine without aura. Auras develop over 5–20 minutes, but last for less than 60 minutes, and are followed by a migraine. One out of three patients with MH experiences aura. MHs are usually frontotemporal, typically unilateral, and are characterized by recurrent attacks of pulsating, intense pain associated with nausea and photophobia. Traditional, nonsurgical treatment of MH can be nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic. Nonpharmacologic treatment of MH consists of avoidance of triggers, which commonly include caffeine, alcohol, or tobacco, and sometimes application of pressure, cold, or heat. Pharmacologic treatment can be further subdivided into acute analgesic, acute abortive, and prophylactic treatment. Acute analgesic treatment consists of pain control, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, benzodiazepines, opioids, and barbiturates. The first-line acute abortive treatment is the use of triptans, although intravenous antiemetics and ergotamine can be used as well. Prophylactic treatment consists of beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and valproic acid.12,13

Box 21.1

Migraine headache diagnostic criteria

Migraine without aura

A. At least five attacks fulfilling criteria B–D

B. Headache attacks lasting 4–72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated)

C. Headache has at least two of the following characteristics:

D. During headache at least one of the following:

Migraine with aura

A. At least two attacks fulfilling criteria B–D

B. Aura consisting of at least one of the following, but no motor weakness:

C. At least two of the following:

D. Headache fulfilling criteria B–D for Migraine without aura begins during the aura or follows aura within 60 minutes

(Adapted from International Headache Society website: http://i-h-s.org.)

Historical perspective

Surgical attempts to treat MH date back to 1931. Walter Dandy removed the inferior cervical and first thoracic sympathetic ganglions in two patients.14 Interestingly, he was able to eliminate MH in both of these patients. However, this pioneer work lacked scientific significance due to a small patient sample size, absence of a control group, and an extremely short follow-up period.

Resection of the greater superficial petrosal nerve in the treatment of various types of unilateral headaches was suggested by Gardner et al. in 1946.15 Twenty-six patients underwent surgery, nine of whom were felt to have unilateral MH, including seven women and two men. All patients with MH observed either complete elimination or significant improvement. Two patients had initial improvement, but the MH recurred after 7–8 months. The authors concluded that the surgery was more successful in patients with MH than for other indications. The patients, however, reported a reduction in tear production and dryness of the nose. Some patients developed corneal ulcerations.

Murillo, in 1969, introduced resection of the temporal neurovascular bundle for control of MH.16 This surgery included removal of the superficial temporal artery and auriculotemporal nerve. The procedure was effective in elimination of MHs in 30 of 34 patients. This report, however, did not include the length of follow-up, nor was there a control group for this clinical trial.

An occipital neurectomy was suggested for patients with occipital MH and neuritis by Murphy in 1969.17 This operation was performed on 30 patients, 15 males and 14 females. Eighteen patients had excellent results, seven had good results, three had fair, and two patients had poor results. Many of these patients, however, had less than 1 year of follow-up. Murphy’s report did not indicate the incidence of anesthesia or paresthesia in the occipital region, nor did it outline any other adverse effects resulting from the surgery.

In 1982, Maxwell reported trigeminal gangliorhizolysis for treatment of MHs in eight male patients through percutaneous delivery of radiofrequency.18 The patients had moderate to significant relief of MH with no reported complications.

The elimination of MH in two patients who underwent endoscopic forehead rejuvenation with resection of the corrugator supercilii muscle prompted our team to conduct a retrospective study on patients who had undergone endoscopic forehead lift.19 Thirty-nine out of 249 patients fulfilled the International Headache Society criteria for MH (Box 21.1). Twenty-nine patients (74.4%; all women) experienced migraine without aura, whereas 10 patients (25.6%; one man and nine women) had migraine with aura. Thirty-one of 39 patients (79.5%) experienced either complete elimination or improvement of the MHs immediately after surgery. The follow-up period averaged 47 months (5–122 months).

The results of the few published studies on the effects of BTX-A (Botox, Allergan, Irvine, CA) on MH20–23 and the above-mentioned study led us to the conclusion that the corrugator supercilii muscle must have a major role in the elimination/reduction of MH, since deactivation of this muscle was the only common denominator of these observations. As a result, a prospective pilot study was designed.24 Twenty-nine patients who were confirmed to have MH (2–12 MHs per month) underwent injection of 25 U Botox into each corrugator supercilii muscle: 16 observed complete elimination of MHs, eight noted significant improvement, and five had minimal to no response. Twenty-two of 24 of patients responded favorably to the injection of Botox; surgical decompression of the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves was done by removal of the corrugator supercilii and depressor supercilii muscles. This group included 18 women and four men ranging in age from 24 to 58 years old. The ZTBTN was also detached. Of the 22 patients who underwent surgery, 21 (95.5%, P < 0.001) observed an improvement in MH. Ten patients (45.5%, p < 0.01) noted elimination of MHs and 11 (50.0%, P < 0.004) noted a significant improvement. The average intensity of MH for the entire surgical group was reduced from 8.9 to 4.1 (P < 0.04) on an analogue scale of 1–10, and the frequency changed from 5.2 to an average of 0.8 (P < 0.001) per month. When the group with improvement only was analyzed, the intensity fell from 9.0 to 7.5 and the frequency changed from 5.6 to 1.0 MHs per month. Only one patient failed to notice an improvement. The average follow-up was 347 days. Shortly after, the rhinogenic and the greater occipital trigger sites were discovered as major trigger sites on those who did not have complete elimination of MHs after injection of BTX-A, bringing the number of major trigger sites to four. Anatomical studies were performed25,26 and minor trigger sites were also identified.27

A prospective randomized study was conducted28 on 125 patients diagnosed with MHs: 100 were randomly assigned to the treatment group and 25 served as controls. Patients in the treatment group were injected with BTX-A for identification of trigger sites. The 25 patients in the control group received an injection of 0.5 mL of saline as placebo. Eighty-nine patients who noted improvement in their MHs for 4 weeks underwent surgery. Eighty-two of the 89 patients (92%) in the treatment group who completed the study demonstrated at least 50% reduction in MH frequency, duration, or intensity compared with the baseline data; 31 (35%) reported elimination and 51 (57%) experienced improvement over a mean follow-up period of 396 days. In comparison, three of 19 control patients (15.8%) recorded a reduction in MH during the 1-year follow-up (P < 0.001), and no patients observed elimination.

In 2009, a placebo-controlled study was published by our team.29 Seventy-five patients with moderate to severe MH were randomly assigned to receive either actual or sham surgery in their predominant trigger site. Fifteen of 26 in the sham surgery group (57.7%) and 41 of 49 in the actual surgery group (83.7%) experienced at least 50% reduction in MH. Furthermore, 28 of 49 patients in the actual surgery group (57.1%) reported complete elimination of MH, compared with only one of 26 patients in the sham surgery group (3%) (P < 0.001). Compared with the control group, the actual surgery group demonstrated statistically significant improvements in all validated MH measurements at 1 year.

In another study from Vienna, Austria,30 the authors followed our initial report24 and removed the corrugator supercilii muscle through a transpalpebral incision. The lead author of this report, a plastic surgeon who suffered from MHs, persuaded another colleague to operate on him following the initial methods developed by our group. Having enjoyed a successful outcome, he commenced the study summarized here. From the entire group of 60 patients, 17 (28.3%) reported total relief from migraine, 24 (40%) significant improvement, and 19 (31.6%) minimal or no change in their MHs after a minimum follow-up period of 6 months. This study included only a single-site surgery before the other trigger sites were discovered and BTX-A was not utilized for patient selection, which with all likelihood would have increased the success rate. From the above-mentioned studies, it is evident that whenever the peripheral-to-central trigeminal pathway is interrupted, relief of migraine pain can be expected in most patients. These reports were later confirmed by Poggi et al.31

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Preoperative history and considerations

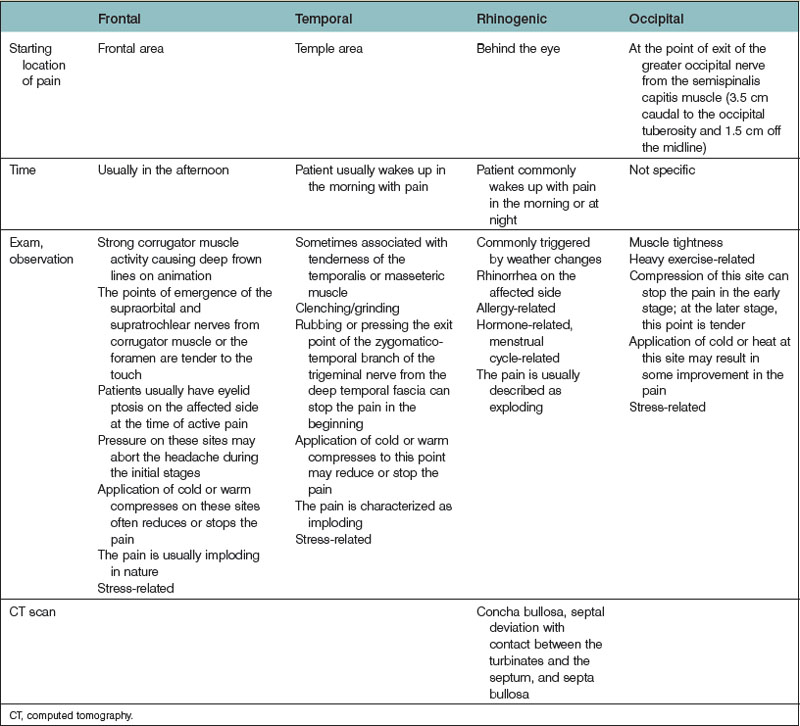

Surgical treatment of a MH should only be considered after the diagnosis of MH is confirmed by a neurologist and more serious causes of headaches have been excluded. The proper surgical candidate is someone whose headaches are not controlled with traditional medical treatment and who has an acceptable surgical risk. Pregnant and nursing women are also typically excluded from surgical consideration. The constellation of symptoms leads the examiner to suspect the potential trigger site (Table 21.1), which is further validated by physical examination.28,32 The salient piece of information that helps to identify the trigger site is the site from which the pain starts. The patient is asked to complete a migraine form asking a number of critical questions. Keeping a monthly diary of MH prior to the surgery may provide more reliable information.

Table 21.1 The constellation of symptoms that aid in the diagnosis of migraine headache trigger sites

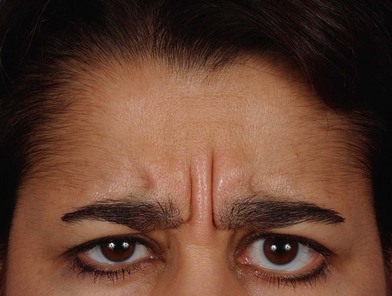

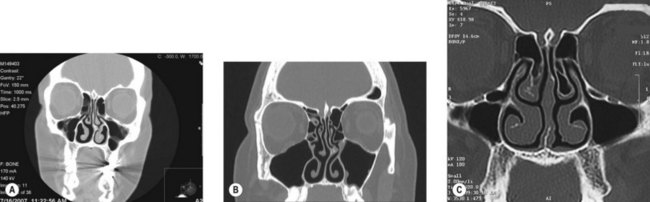

Hypertrophy of the corrugator supercilii muscle with vertical frown lines is a common finding and might be obvious in patients with a frontal trigger site (Fig. 21.1). The nasal exam includes a physical exam with or without endoscopic examination, which must be performed to detect septal deviation and turbinate hypertrophy with contact points between the septum and turbinates, concha bullosa and septa bullosa, and the findings are confirmed using a CT scan of the septum and sinuses (Fig. 21.2).