Surgical Correction of Nonunion of Mandible Fracture

Howard D. Wang

Arthur J. Nam

Amir H. Dorafshar

DEFINITION

Nonunion of a mandible fracture occurs when there is a failure of the fracture to heal within an adequate amount of time.

Nonunion of a mandible fracture usually leads to pain, malocclusion, and inability to masticate.

Haug and Schwimmer defined this time period as 8 weeks after surgical management or 4 weeks without treatment.1

ANATOMY

The mandible consists of two hemimandibles fused at the midline symphysis, and injuries can be classified based on the location of the fracture.

The most common location of nonunion is the body, followed by the angle region of the mandible.2

PATHOGENESIS

Nonunion of mandible fractures generally occurs as a result of inadequate fracture stabilization, inaccurate reduction, infection, or delayed treatment.

Other risk factors associated with nonunion include injury characteristics, such as teeth in the fracture line or presence of multiple mandible fractures, and patient characteristics such as edentulous mandible, tobacco use, alcohol abuse, immune deficiency, diabetes mellitus, or patient noncompliance.2

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

History

A thorough history should include the patient’s chief complaint and symptoms such as pain, trismus, fever, and drainage.

Reviewing all preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data from previous surgical treatments related to the initial mandibular trauma is critical in identifying the etiology of nonunion.

Patient comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, or polysubstance abuse should be elicited as these factors can contribute to the ultimate outcome.

Physical examination

Patient’s facial height, width, and symmetry are assessed.

The mandible is palpated for tenderness, bony deformities, presence of abscess, and instability.

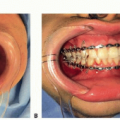

Intraoral examination is performed with a focus on the occlusion, dental decay, oral hygiene, presence of purulent drainage, and condition of the oral mucosa.

Any existing deficits in the sensory distribution of the inferior alveolar nerve and motor innervation of marginal mandibular branch of facial nerve are documented.

IMAGING

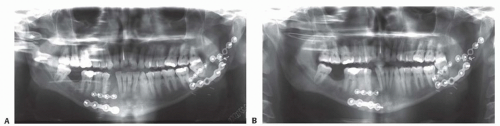

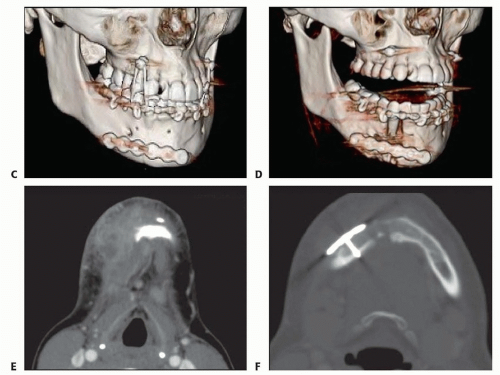

Plain x-ray films (facial series, panoramic) can be used for postoperative evaluation to identify an enlarging gap in the fracture line, presence of irregular radiolucency, and/or hardware loosening (FIG 1A, B).

Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) with threedimensional formatting has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of the fracture site, extent of soft tissue infection, and associated osteomyelitis (FIG 1C-F).

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Mandibular nonunions are often associated with infections of the soft or bony tissue, which require antibiotic therapy.

Choice of antibiotics should focus on coverage of Grampositive and anaerobic organisms with subsequent culturedirected antibiotics.

The duration of treatment will depend on whether the infection affects the soft tissue alone or if osteomyelitis is present, which may require 4 to 6 weeks of intravenous treatment.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The general algorithm for management of nonunion of mandible fractures includes debridement of nonviable bone to establish fresh bony edges, bone grafting when there is a lack of bone-to-bone contact, and rigid fixation to achieve proper stabilization.

Occlusion should first be established with maxillomandibular fixation (MMF). It is important to ensure that the condyles are well seated superiorly in the glenoid fossa.

Although the presence of infection does not always necessitate removal of existing hardware, mandibular nonunions generally result due to inadequate stabilization, and existing hardware will usually need to be removed.

Any evidence of hardware loosening or fracture instability is a clear indication for hardware removal.

Debridement of devitalized or infected bone back to healthy, bleeding bone is critical for both clearance of infection and achieving bony union.

Teeth in the line of fracture should be extracted, especially in the presence of infection.4

A bone biopsy should be performed to diagnose and guide treatment of osteomyelitis.

Traditionally, management of infected mandibular nonunions was performed with prolonged MMF or external fixation to control occlusion while the infection is treated and the soft tissue is healing. This was done to avoid placement of hardware in an infected field.5

More recent work suggests that instability is a primary contributor to the development of infected mandible fractures and that the use of rigid internal fixation after adequate debridement is a viable treatment option to achieve resolution of infection and bony union.6

Therefore, rigid internal fixation has become the preferred method and should be performed using a load-bearing reconstruction plate with at least three bicortical locking screws on each side of the fracture.

The closest screw should be placed at a minimal distance of 7 to 10 mm from the fracture edge.7

If the bone gap is small, bony union can be achieved with improved rigid fixation. However, larger gaps with inadequate bone contact will require autogenous bone grafting.

Cancellous bone grafts packed tightly into the defect area have a high success rate by improving osteogenic potential.8

Vascularized bone flaps (with or without associated skin paddle) are indicated in cases where a critical-sized defect greater than 6 cm is present, when previous bone grafting has failed, or when severe soft tissue contracture is present.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree