Surgical Approaches for Vitiligo

Rafael Falabella

Vitiligo is a relatively common pigmentary disorder characterized by patches of depigmentation. The disease affects 1% to 2% of the population and shows no racial or ethnic predilection. Vitiligo is indeed a disfiguring and psychologically devastating disease. The disorder may be imperceptible in people with Fitzpatrick skin types I and II but is striking in darker racial ethnic groups (Fig. 15-1). Patients with vitiligo experience profound psychological trauma relating to the cosmetic deformity. Psychological profiles have documented perceived job discrimination, low self-esteem, suicidal ideation, and difficulty in interpersonal relationships.1,2 The effects of vitiligo are particularly devastating in darker racial ethnic groups.

The precise cause of vitiligo is unknown. Autoimmune, genetic, neural, biochemical, self-destructive, and viral mechanisms have been suggested.1 Myriad clinical observations and studies support an immune mediated pathogenesis of vitiligo. Vitiligo has been reported in association with autoimmune endocrinopathies and autoimmune diseases. Thyroid disorders, in particular Hashimoto Thyroiditis and Grave Disease, are the most common associated diseases. Other disorders have included diabetes mellitus, alopecia areata, pernicious anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome, and psoriasis. In a recent survey of 2,624 vitiligo probands in North America and the United Kingdom, a significant increase in six autoimmune diseases was reported in vitiligo probands and first-degree relatives.2 These diseases included vitiligo, thyroid disease (predominantly hypothyroidism), pernicious anemia, Addison Disease, systemic lupus erythamatosus, and inflammatory bowel disease. Despite the difficulties inherent in replenishing the epidermis with melanocytes, recent significant advances have been made in the treatment of vitiligo. The best therapies for vitiligo include medical and surgical approaches (Table 15-1). These include topical steroids, vitamin supplementation, topical immunomodulators (e.g., tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB) phototherapy, and targeted light units. Grafting has been shown to be effective for localized lesions. Most recently, targeted phototherapy systems have proved effective in the treatment of localized vitiligo. About 70% repigmentation may be achieved with medical therapies, either topically or systemically, but there are difficult areas to repigment, such as the acral part of the extremities, lips, and genitalia. When vitiligo becomes refractory to medical treatment, surgical techniques become an important alternative.

In this chapter, a review of repigmentation in vitiligo by surgical methods is described, emphasizing the peculiarities of ethnic skin in regard to these treatments. The basic principles of melanocyte transplantation, indications, contraindications, description of the surgical techniques, and complications are discussed.

Understanding Vitiligo from the Surgical Point of View

It is not simple to understand why surgical interventions are useful in vitiligo, a condition that was treated medically for many years. However, about 25 years ago, transplantation of melanocytes were added to the armamentarium of vitiligo therapies after observing that appropriate selection of patients was an essential condition sine qua non for repigmentation success.

Vitiligo is, in general terms, a progressive disease, and it is frequently observed that lesions enlarge gradually, leading to depigmentation that may affect any anatomical area in a symmetrical distribution. In time, after years of progression, some lesions become stationary and may spontaneously repigment, at least partially—a phenomenon that can be seen around or within depigmented areas as multiple spots or pigmentation islands. On the other hand, a smaller percentage of patients, usually younger than the previous group, develop unilateral lesions that have a faster course and after several months may come to a halt without having further depigmentation; some of these lesions may also develop some degree of spontaneous and partial repigmentation.

During medical therapy, pigment cells arise and proliferate from three different sources: (i) the pilosebaceous

unit, providing the highest number of cells, which migrate from the external root sheath toward the epidermis;3 (ii) spared epidermal melanocytes not affected during depigmentation;4 and (iii) the border of lesions, migrating up to 2 to 4 mm from the edge. Immature melanocytes around the follicular ostium, expressing the C-kit protein, may also be an important part of the melanocyte reservoir and could replace pigment cells in vitiligo that disappeared by destruction or apoptosis.5 When pigment cells are no longer available from these sources, medical therapy is no longer useful. Under conditions of stability, however, repigmentation may be possible by melanocyte grafting or transplantation, because the pathogenic mechanisms causing depigmentation are arrested; hence, melanocyte destruction will not occur when new cells are implanted. Nevertheless, if depigmentation is still in progress or new lesions develop, the condition is active, and melanocyte transplantation must not be considered as a therapeutic option.

unit, providing the highest number of cells, which migrate from the external root sheath toward the epidermis;3 (ii) spared epidermal melanocytes not affected during depigmentation;4 and (iii) the border of lesions, migrating up to 2 to 4 mm from the edge. Immature melanocytes around the follicular ostium, expressing the C-kit protein, may also be an important part of the melanocyte reservoir and could replace pigment cells in vitiligo that disappeared by destruction or apoptosis.5 When pigment cells are no longer available from these sources, medical therapy is no longer useful. Under conditions of stability, however, repigmentation may be possible by melanocyte grafting or transplantation, because the pathogenic mechanisms causing depigmentation are arrested; hence, melanocyte destruction will not occur when new cells are implanted. Nevertheless, if depigmentation is still in progress or new lesions develop, the condition is active, and melanocyte transplantation must not be considered as a therapeutic option.

Table 15-1 Medical and surgical therapies for vitiligo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnic Skin and Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a socially difficult condition to deal with in patients with fair complexions, because hypopigmentation is easily detected by other persons, some of whom may have a feeling of rejection toward affected individuals. This situation may be more difficult for patients with dark ethnic skin, because depigmented lesions are similar to that of Caucasians, but their appearance as compared with adjacent normally pigmented skin discloses a remarkable contrast that make this condition much more noticeable and unsightly. Social rejection leading to difficulties in daily life and job opportunities may provoke anxiety, depression, and impaired self-image. In some cultures, discrimination, familial stigmatization, and sometimes divorce problems may affect patients with vitiligo.6 Dark-ethnic-skin patients with vitiligo deserve

to be treated with the best of our knowledge to improve their appearance and reincorporate them into an active social life.

to be treated with the best of our knowledge to improve their appearance and reincorporate them into an active social life.

Pathogenic Aspects: Active Versus Inactive Vitiligo

Although the cause of vitiligo is unknown, we are not completely in darkness, because multiple factors have been identified in the last 3 decades in relation to its pathogenesis. It is remarkable that an asymptomatic disease such as vitiligo—without significant inflammation and producing a “minor” change such as loss of pigmentation—is so complex that to date, the secrets of its pathogenesis have not been completely unraveled.

Immunological alterations, both humoral and cellular;7 autocytotoxic damage to pigment cells;8 generation of free radicals and hydrogen peroxide;9 intrinsic damage of the rough endoplasmic reticulum leading to melanocyte damage;10 pathologic changes of fine nerve endings and neuropeptide disturbances;11 associated endocrine ailments and organ specific antibodies;12,13 and other related findings have been described as pathogenic factors, some of which are inducers of toxic and/or inhibitory effects on pigment cells; nevertheless, the sequence of events leading to depigmentation is yet to be determined. It may also be possible that all of these, as well as other unknown factors, may contribute to depigmentation. It is not clear either if there are vitiligo subsets that correspond to clinical presentations with different pathogenic mechanisms. To summarize, although the ultimate cause of vitiligo is not completely known, this condition reflects profound immunological alterations and other molecular defects originating pigment cell destruction.

When lesions are enlarging or new lesions appear, we may speak of active or unstable vitiligo, which is resistant to any type of surgical therapy. After complete stabilization, vitiligo becomes inactive or stable and may be treated by grafting or transplantation. It is interesting that melanocytes may be present in depigmented skin after years of onset4 and may still respond to medical therapy under appropriate stimulation.

Clinical Forms of Vitiligo

Several classifications for vitiligo have been proposed, but for practical purposes, most patients can be classified in two major forms: Unilateral and bilateral vitiligo.14

Unilateral vitiligo (segmental, asymmetric vitiligo) may develop in 10% to 20% of affected individuals, and it is more commonly observed in young patients before the age of 20. Depigmentation occurs on one side of the cutaneous surface, running a rapid course during several months; following stabilization, it does not progress thereafter. The depigmented areas are limited to one anatomical region in a quasidermatomal distribution. Repigmentation is not always possible with medical treatment, but surgical techniques are the best indication for this vitiligo type, with most publications disclosing high rates or complete repigmentation.15,16

Bilateral vitiligo (vitiligo vulgaris, symmetrical vitiligo) accounts for about 80% to 90% of vitiligo patients. In the majority of them, lesions begin as small depigmented macules, slowly enlarging during several years, in a bilateral and often symmetric distribution, sometimes with partial regression but more commonly in a progressive manner. In a relatively small group of individuals so affected, the condition becomes stable, and in about 50% of such cases, repigmentation may be obtained by melanocyte transplantation.17

Recently repigmentation of stable vitiligo lesions on genitalia was successfully reported in three patients with noncultured melanocyte keratinocyte transplantation. Although this is an important achievement, appropriate selection is an important issue when treating such patients at this anatomical site.18

Selection of Patients for Surgical Repigmentation

Melanocyte transplantation is only useful and indicated when lesions become refractory to medical treatment but particularly when stabilization and no further progression of vitiligo occurs. It is important to consider several items to be evaluated in patients when surgical treatment becomes an option.

Stable vitiligo

So far, there is no objective manner to detect complete vitiligo stability, but there are several ways to suggest that vitiligo has reached this point:

No progression of lesions during at least 2 years (although a nonprogressive macule may be active and may not respond to surgical treatment, and a slow-progressing macule is difficult to evaluate).

Spontaneous repigmentation (stable vitiligo is highly possible in this case).

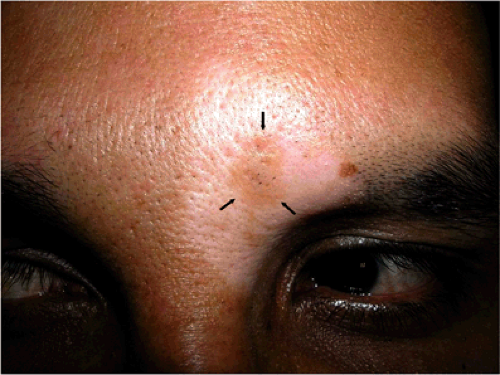

Results of minigrafting test: When repigmentation around 4 to 5 minigrafts (1 or 1.2 mm), implanted 3 to 4 mm apart within a depigmented lesion, occurs, the possibilities of repigmentation may be high, and a successful response may be anticipated in 95% of patients (Fig. 15-1).19 Sometimes it is advisable to perform an extended test with multiple minigrafts, particularly on poorly responsive anatomical locations (Fig. 15-2). So far, this test is the most accurate evidence of vitiligo stability, and recent studies suggest its reliability and validation.20

No new Koebner phenomenon developing, including the donor site for the minigrafting test.

Unilateral vitiligo, which is by definition the most stable form of the disease with excellent repigmentation response after surgical treatment, as demonstrated in numerous publications.21 In bilateral vitiligo, only half of these patients may improve with surgical therapy16,19 after reaching the point of stability, which usually occurs many years after onset.

New proposals for defining stable vitiligo are needed, but until they become valid, the previous parameters should be kept in mind.

Age for procedures

Although transplantation methods are invasive procedures and not recommended in children, sometimes motivated patients around the age of adolescence can be treated under sedation or general anesthesia. Adults can be treated at any time depending on their interest in surgical repigmentation.

Treatment of the dorsum of hands

Surgical methods and size of lesions

For small- or medium-size lesions, simple methods, such as minigrafting and suction epidermal grafting, are useful. For extensive depigmented defects, in vitro culture techniques may be required,24 but serial treatments with simple methods can also be appropriate.

Patient’s expectations

Repigmentation is not always comparable with normally pigmented skin, and the final results vary considerably from patient to patient. However, most individuals are pleased with the achieved results; minor imperfections are far less important than the noticeable repigmentation of vitiliginous skin, mainly in ethnic skin patients with dark complexion. Sometimes, surgical repigmentation may look even better than what is observed in many patients after medical therapy.

Psychological aspects

Some patients with high emotional trauma because of depigmentation may seek advice for invasive procedures. However, a psychological evaluation may be needed to ascertain the real need for surgical treatment.

Photographic records

Illustrations are recommended to help in determining the percentage of improvement, quality of repigmentation, and possible side effects.

Achromic versus hypopigmentated lesions

The best lesions to treat are those completely depigmented in patients with skin types III to VI. Hypopigmented lesions do not repigment as well, and sometimes moderate and permanent hyperpigmentation occurs.

Serial procedures to complete repigmentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree