8.3 Superior or medial pedicle

Synopsis

Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty using a superior or medial pedicle has the advantage of improved long-term projection of the breasts, along with less scarring than inverted-T scar/inferior pedicle breast reduction techniques.

Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty using a superior or medial pedicle has the advantage of improved long-term projection of the breasts, along with less scarring than inverted-T scar/inferior pedicle breast reduction techniques.

A unique aspect of our technique is the use of a superior or medial dermoglandular pedicle for transposition of the nipple-areola complex, depending on its position with respect to the mosque dome skin marking pattern.

A unique aspect of our technique is the use of a superior or medial dermoglandular pedicle for transposition of the nipple-areola complex, depending on its position with respect to the mosque dome skin marking pattern.

Our method of pedicle selection and design has likely prevented complete nipple loss, and we have not had any necrosis of the nipple-areola complex either.

Our method of pedicle selection and design has likely prevented complete nipple loss, and we have not had any necrosis of the nipple-areola complex either.

Evolution of the technique

Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty using a superior or medial pedicle has the advantage of improved long-term projection of the breasts, along with less scarring than inverted-T scar/inferior pedicle breast reduction techniques. We believe that it is the inferior wedge resection of the redundant breast tissue that contributed to breast ptosis, and subsequent suturing of the medial and lateral pillars that result in coning of the breast and are responsible for the long-term shape.1 In particular, the parenchymal pillar sutures through the superficial fascial system are critical for providing support for the remaining breast tissue, and likely help to prevent pseudoptosis.2,3 In addition, vertical scar techniques do not violate the structural integrity of the inframammary crease, thus preventing downward migration of the inframammary crease and subsequent pseudoptosis, a problem commonly seen with breast reduction techniques that involve a horizontal scar.3

Reduction mammaplasty finishing with a vertical scar was first described by Arie in 1957.4 However, this technique did not gain popularity because the vertical scar often extended below the inframammary crease leaving an unsightly scar. Years later, Lassus5–7 and Lejour8–10 renewed interest in vertical scar reduction mammaplasty and are responsible for much of the pioneering work. In 1969, Lassus5–7 developed a technique using a superior dermoglandular pedicle for transposition of the nipple-areola complex; a central en bloc excision of skin, fat, and gland; and a vertical scar to finish. The shape of the breast was produced by reapproximating the medial and lateral pillars with only suturing of the skin. In 1994, Lejour8–10 described a modification of Lassus’ technique in which pre-excision liposuction was used to eliminate fat contributing to breast volume; the skin surrounding the excised area was undermined to facilitate gathering of the vertical scar; the superior dermoglandular pedicle was sutured to the pectoralis fascia; and sutures were used in the breast parenchyma to reapproximate the pillars producing a more durable breast shape. Gathering of the skin of the vertical wound was used to keep the scar above the inframammary crease. In 1999, Hall-Findlay11–14 described a modification of Lejour’s technique using a mosque dome skin marking pattern; a full thickness medial dermoglandular pedicle to transpose the nipple-areola complex; no skin undermining; no suturing of the pedicle to the pectoralis fascia; and liposuction only rarely to reduce breast volume. Hall-Findlay’s technique has since become the most commonly performed limited incision breast reduction technique as reflected in the 2002 American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery15 and 2006 American Society of Plastic Surgeons surveys16 of board-certified plastic surgeons. These findings were echoed by a survey of members of the Canadian Society of Plastic Surgeons in 2008.17

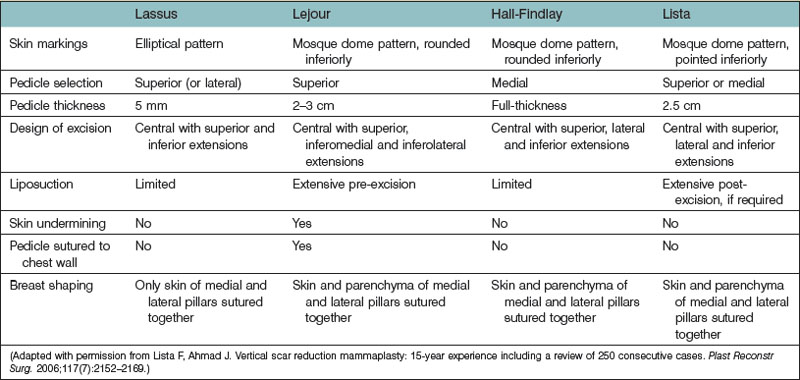

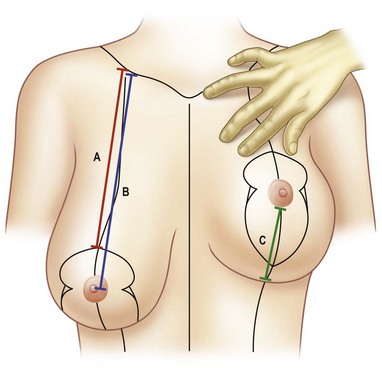

In 2006, we described our technique for vertical scar reduction mammaplasty that uses a mosque dome skin marking pattern; transposition of the nipple-areola complex on a superior or medial dermoglandular pedicle, depending on its position with respect to the skin markings; an en bloc excision of skin, fat, and gland; postexcision liposuction; and wound closure in two planes, including parenchymal pillar sutures and gathering of the skin of the vertical wound using four-point box stitches (Table 8.3.1).1 Since 1989, we have performed this technique on over 2000 patients requiring breast reduction resulting in consistently good breast shape, while leaving less scarring than in more commonly performed breast reduction techniques. Initially, we performed breast reduction techniques utilizing a variety of pedicles in combination with an inverted-T scar. However, as our practice demographic evolved, we saw younger women presenting for breast reduction, who were not only interested in experiencing relief of their symptoms secondary to mammary hypertrophy but who were also concerned with the amount of scarring that resulted from the procedure and the long-term appearance of their breasts. This necessitated a critical re-evaluation of our approach to breast reduction and an evolution to our technique for vertical scar reduction mammaplasty to address these issues. These concerns have also been studied by other authors18–20 who have reported that women undergoing breast reduction prefer less scarring and are more dissatisfied with the horizontal component of the inverted-T scar than the vertical component following breast reduction.20 In 2008, we reported our results at long-term follow-up, showing that pseudoptosis does not occur, attesting to the maintenance of breast shape and projection following this procedure.2 In this study, three measurements were recorded at each visit: the shortest distance between the inferior edge of the clavicle and the planned postoperative position of the superior border of the nipple-areola complex, the shortest distance between the inferior edge of the clavicle and the nipple, and the distance between the inframammary crease and the inferior border of the nipple-areola complex (Fig. 8.3.1). Compared with preoperative skin markings, the nipple-areola complex was located significantly higher at both early and long-term follow-up.2 We attribute the superior movement of the nipple-areola complex to excision of central and inferior pole breast tissue that unweights the remaining breast tissue including the nipple-areola complex allowing for elastic recoil of the superior pole skin. In addition, suturing of the medial and lateral pillars produces coning of the breast and pushes the nipple superiorly. This coning effect also causes the lax skin of the superior aspect of the breast to be distributed in a circumhorizontal direction as opposed to distribution in an inferior direction, as would be the case for breast reductions performed using the inverted-T scar pattern.2 To accommodate for this, we adjusted the skin marking technique so that the superior border of the nipple-areola complex is marked at the level of the inframammary crease. At 4 years, the distance from the inframammary crease to the inferior border of the nipple-areola complex was significantly shorter, confirming that pseudoptosis does not occur after vertical scar reduction mammaplasty.2

A unique aspect of our technique is the use of a superior or medial dermoglandular pedicle for transposition of the nipple-areola complex, depending on its position with respect to the mosque dome skin marking pattern. Our method of pedicle selection and design has likely prevented complete nipple loss, and we have not had any necrosis of the nipple-areola complex either. A closer study of the blood supply to the nipple-areola complex provides a better understanding of why the selection of a superior or medial pedicle provides a reliable blood supply for transposition of the nipple-areola complex. Many varying observations of the blood supply to the breast have been given since Manchot’s21 1889 description. More recently, van Deventer22 performed anatomical studies on 15 female cadavers in an attempt to further clarify the blood supply to the nipple-areola complex and found a large variation in the pattern of its blood supply. An important observation was that in all breasts, the nipple-areola complex received a blood supply medially or superiorly from one or more perforating arteries from the superior four perforating branches of the internal thoracic artery. The third perforator most frequently contributed blood supply to the nipple-areola complex in 47.5% of breasts, while the second perforator contributed in 25%, the first perforator in 15% and the fourth perforator in 12.5%. There were abundant anastomoses around the nipple-areola complex. From this study, van Deventer et al.23 concluded that the nipple-areola complex generally has a dual blood supply with the internal thoracic-anterior intercostal artery system providing blood supply from medio-inferiorly and the lateral thoracic artery and other minor contributors providing blood supply from latero-superiorly, with the most reliable source of blood supply arising from the internal thoracic artery. Information from this study would lead us to believe that a superior pedicle may have either an axial or random blood supply while a medial pedicle is more likely to have an axial blood supply. Our method of pedicle selection limits the length of the superior pedicle allowing it to provide a reliable blood supply to the nipple-areola complex whether it happens to be axial or random. The use of a superior pedicle is limited to nipple-areola complexes lying within the roof of the mosque dome, allowing this pedicle to receive superior, medial and lateral blood supplies. This reliable superior pedicle was the most commonly utilized pedicle in our series.1 In cases of mammary hypertrophy with greater degrees of ptosis, we use a medial pedicle, which is more likely to have an axial blood supply to reliably perfuse the nipple-areola complex when it must be transposed greater distances. Another anatomical study by Michelle le Roux et al.24 examined the neurovascular anatomy on 11 female cadaveric breasts. They reported that the arterial supply to the superomedial pedicle originated from a single dominant vessel while the venous drainage was through an extensive branching network. Along with intercostal nerve branches that innervated the pedicle, the blood supply coursed through the pedicle in a superficial plane. They concluded that deepithelialization or thinning of the superficial aspect of the superomedial pedicle could lead to vascular compromise or denervation of the nipple-areola complex. Instead, they recommended resection should be done from the deep surface or the base of the pedicle if needed. This study supports the safety of the partial thickness superior or medial pedicle design which we use in our technique. The use of a full thickness pedicle can be cumbersome, not only preventing adequate volume reduction but also causing difficulty transposing the nipple-areola complex to its new location. In addition, a full thickness pedicle can become kinked or tethered leading to vascular compromise of the nipple-areola complex; the partial thickness pedicle design transposes the nipple-areola complex easily to its new location.

Patient selection

Symptoms

Kerrigan et al.25 reported an evidence-based definition of medical necessity for breast reduction in an effort to establish clear, practical, objective, and fair criteria that could be applied by physicians to help differentiate women seeking breast reduction primarily for symptom relief versus aesthetic improvement. They identified seven symptoms specific to breast hypertrophy: upper back pain, rashes, bra strap grooves, neck pain, shoulder pain, numbness, and arm pain. Results of this study established that women reporting at least two of seven physical symptoms all or most of the time improved to a significantly greater extent than women reporting less than two symptoms all or most of the time. Their data suggested that women reporting at least one of seven physical symptoms may also report greater improvement than those with no symptoms all or most of the time. We have found this definition of medical necessity useful in evaluating patients that will benefit most from breast reduction by reduction of their symptoms associated with mammary hypertrophy.

Patient characteristics

We have performed vertical scar reduction mammaplasty exclusively on over 2000 patients presenting for breast reduction. In 2006, we published our experience with 250 consecutive patients treated between November of 2000 and December of 2003.1 In this clinical series, the average age of the patients was 38.5 years (range, 15–76 years) and the average body mass index was 28.8 kg/m2 (range, 17.3–46.3 kg/m2). The average weight of tissue excised per breast was 526 g (range, 10–2020 g). Liposuction was performed in 78.4% of cases and the average volume liposuctioned per breast was 140 ml (range, 50–500 ml). The average total reduction per breast (including liposuction when performed) was 636 g (range, 60–2020 g).

In addition, we analyzed complications based on body mass index, amount of reduction, pedicle selection, and use of liposuction.1 Although there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of complications between groups for amount of reduction, pedicle selection, and use of liposuction, there was a statistically significant difference between groups for body mass index with complications occurring less frequently in patients of normal weight (body mass index, 18.5–25.0 kg/m2). These findings have also be corroborated by other authors.26,27 Since this study was published, we have limited performing this procedure to patients with a body mass index <35 kg/m2. Patients presenting for breast reduction with a body mass index >35 kg/m2 are advised to lose weight prior to undergoing this procedure to decrease their risk for complications including superficial wound dehiscence and fat necrosis.

Along with other authors,7,11 we recommend learning this technique by initially operating on patients with mild to moderate hypertrophy and good skin quality. As more experience is gained, one can progress to performing this technique on patients with greater degrees of mammary hypertrophy and poorer skin quality. Although it is possible to perform this technique on patients with extremely large breasts, it is important for these patients to realize that their postoperative breast size will likely remain larger when compared to other techniques because of the amount of skin preserved with a vertical scar breast reduction. In patients with severe mammary hypertrophy desiring a very small postoperative breast size, this technique is not suitable.

Details of planning and marking

General perioperative care

We routinely perform vertical scar reduction mammaplasty as a day surgery procedure. The average operating time is <70 min.1 Multiple authors have shown that there is no increased risk of complications following breast reduction as a day surgery procedure.27–30 In addition, Buenaventura et al.30 estimated between US$1500 and US$2500 were saved when breast reduction surgery was performed as a day surgery procedure as opposed to requiring inpatient admission, while Nelson et al.17 reported an estimated cost savings of C$873.

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons Patient Safety Committee evidence-based patient safety advisory provides an overview of perioperative steps that should be completed to ensure appropriate patient selection for the ambulatory surgery setting.31 In addition, guidelines for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation,32,33 prevention of pulmonary complications,34,35 and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis36,37 are also available.

Skin marking

The patient is marked preoperatively. In the sitting position, the midline of the chest and the inframammary creases are marked (Fig. 8.3.2). The central axis of the breast is drawn by extending a straight line from the midpoint of the clavicle through the nipple to intersect with the inframammary crease. One hand is inserted behind the breast to the level of the inframammary crease, and this point is projected anteriorly onto the breast and marked (A). This point will be the new location of the superior border of the areola. Since the nipple-areola complex is located significantly higher compared with preoperative skin markings, at both early and long-term follow-up after this procedure, (Fig. 8.3.3) the planned postoperative position of the nipple-areola complex in this technique is approximately 2 cm lower than it would be using an inverted-T scar/inferior pedicle breast reduction technique.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree