Superficial Fungal Infections Janice T. Chussil There are two categories of cutaneous fungal infections, or mycoses, dermatophytes and Candida, and other endogenous yeasts. Superficial infections involve the stratum corneum of skin as well as hair, nails and mucous membranes, whereas deeper fungal infections involve the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The clinical presentation of fungal infections varies depending on the type of fungus, location, and immunologic response of the host. Most mycoses seen in primary care and dermatology are superficial infections. And although they are referred to as “superficial,” if left untreated, they can become debilitating, develop secondary bacterial infections, and spread to other parts of the body or to close contacts. This chapter begins with an introduction to the diagnostic tests and treatment therapies before the discussion of diseases. Clinicians should be vigilant in developing a differential diagnosis, selecting appropriate diagnostic tests, and considering safe and effective therapy.

DIAGNOSTICS

Clinical presentation, along with laboratory findings, should be used to diagnose tinea since it can mimic many other skin diseases. Selection of the diagnostic test is based on access, cost, time, and value of pathogen identification. It should be noted, however, that the value of any fungal examination is only as good as the quality of the specimen submitted for analysis. The appropriate sampling techniques, advantages, and disadvantages for available fungal tests are provided in chapter 24.

• Direct microscopy or KOH preparation is the easiest and most cost-effective test available to clinicians regardless of the practice setting. Scrapings are obtained from the skin, hair, or nails to confirm the presence or absence of hyphae or spores. KOH does not identify the species of dermatophyte.

• Fungal culture is the gold standard for the definitive diagnosis of a fungal infection. It can be sent to a laboratory to provide further diagnostic confirmation, including the specific genus and species of the organism. This is important since some nondermatophyte molds and Candida species can look like dermatophytes under the microscope but will not respond to dermatophyte treatment. Analysis may take 2 to 6 weeks and can be costlier to the patient. This test should be considered for tinea infections that are recurrant or recalcitrant to conventional treatment modalities.

• Dermatopathology performed on a punch biopsy specimen may be helpful if the KOH preparation and/or culture fails to confirm your diagnosis or if you are considering other differential diagnoses. Specimens should be sent for routine histology, including periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), which is used to demonstrate fungal elements. Distal nail clippings can also be sent for histology and can help differentiate onychomycosis from psoriasis.

• Wood’s light examination can be useful in evaluating specific fungal and bacterial infections. In tinea capitis, only the hair from hosts infected by Microsporum canis or M. audouinii will fluoresce blue-green, compared with Trichophyton tonsurans and other species that do not fluoresce. In tinea versicolor, the affected skin will appear yellow-green, and bacterial infections such as erythrasma, caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, fluoresce a bright coral red.

• Dermatophyte testing media (DTM) is a convenient and low-cost in-office test in which clinicians inoculate media with a sample of the skin, hair, or nails. After 7 to 14 days of incubation at room temperature, dermatophytes cause a change in the pH and indicate their presence by changing the medium to a red color. DTM does not identify the species and can have false positives from contaminated samples (some molds, yeasts, and bacteria) or media left for more than 14 days.

ANTIFUNGAL AGENTS

Topicals

Because dermatophytes are limited to the epidermis, topical antifungals are effective and the first-line therapy for most superficial fungal infections. Topical antifungals have very little systemic absorption, resulting in low risk for adverse events or drug interactions. The most common side effects reported are symptoms of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. Many topical antifungals are now available by prescription and over the counter. Selection of the most appropriate agent should be based on the suspected (or cultured) causative organism, severity, body surface area, comorbidities, cost, location(s) of infection, and potential for secondary infection. Severe or recalcitrant dermatophyte infections may require systemic treatment, with associated increased risk for side effects, drug interactions, and complications.

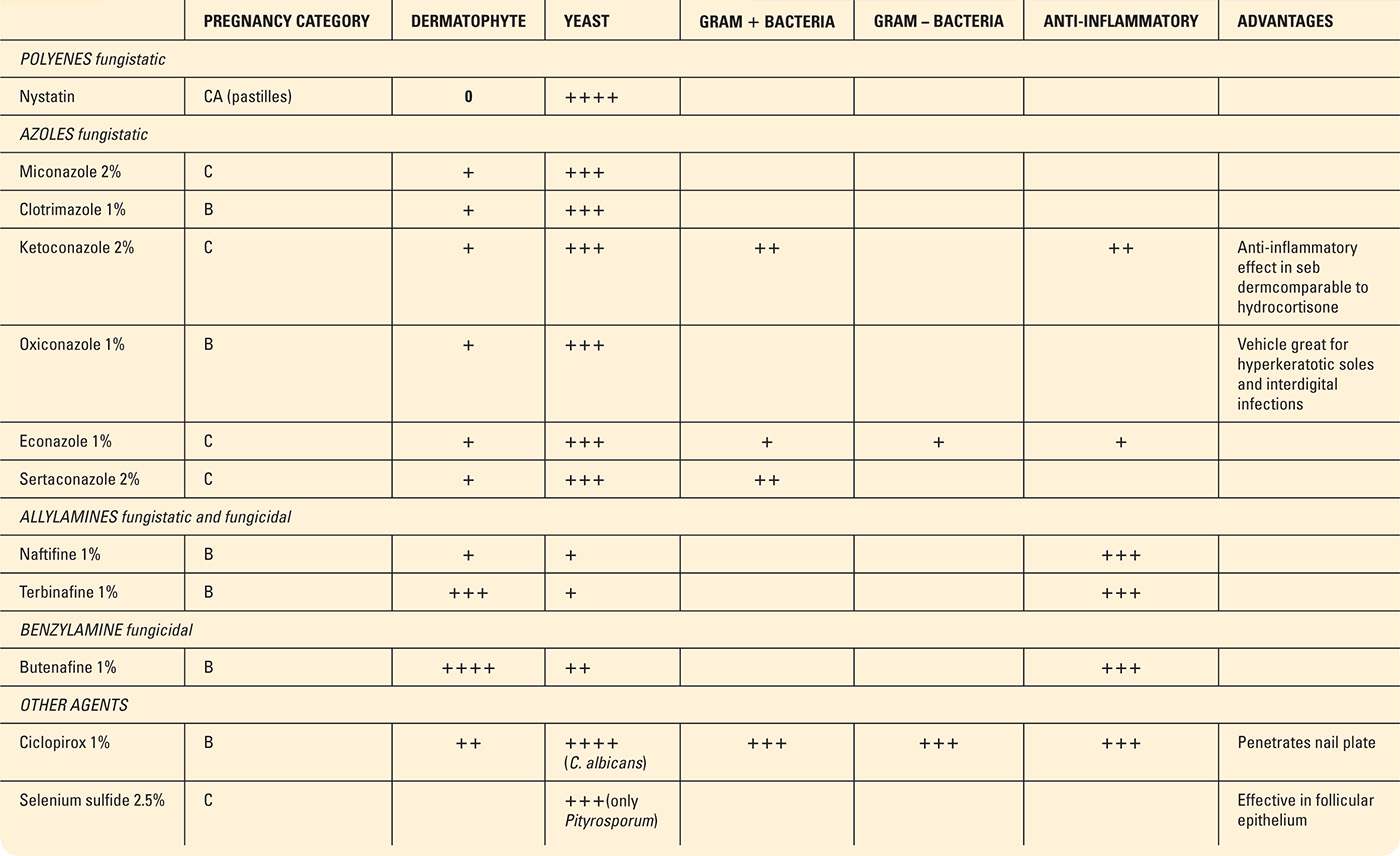

Topical antifungals used for the treatment of mucocutaneous infections belong to one of four classes: polyenes, imidazoles, allylamines/benzylamines, and others (Table 12-1). Polyenes are fungistatic agents effective against Candida but not dermatophytes or Pityrosporum. Azoles are also fungistatic but possess antibacterial as well as anti-inflammatory properties, and are used for dermatophyte, Candida, endogenous yeast, and secondary bacterial infections. The allylamine/benzylamine group has a broader spectrum of antifungal activity and can be both fungistatic and fungicidal. They are the drug of choice for dermatophytes, but relatively weak against Candida. Other topical antifungals include ciclopirox, which has a unique mode of action and structure and is fungistatic, fungicidal, and anti-inflammatory. It is effective against tinea pedis, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, and candidiasis. Ciclopirox nail lacquer 8% is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved topical for onychomycosis since it can penetrate the nail plate.

Comparing Effectiveness of Topical Antifungals on Types of Organisms |

0, no effect or activity against specific organism; +, mildly effective activity; ++, moderately effective; +++, strongly effective; ++++, most effective.

Systemics

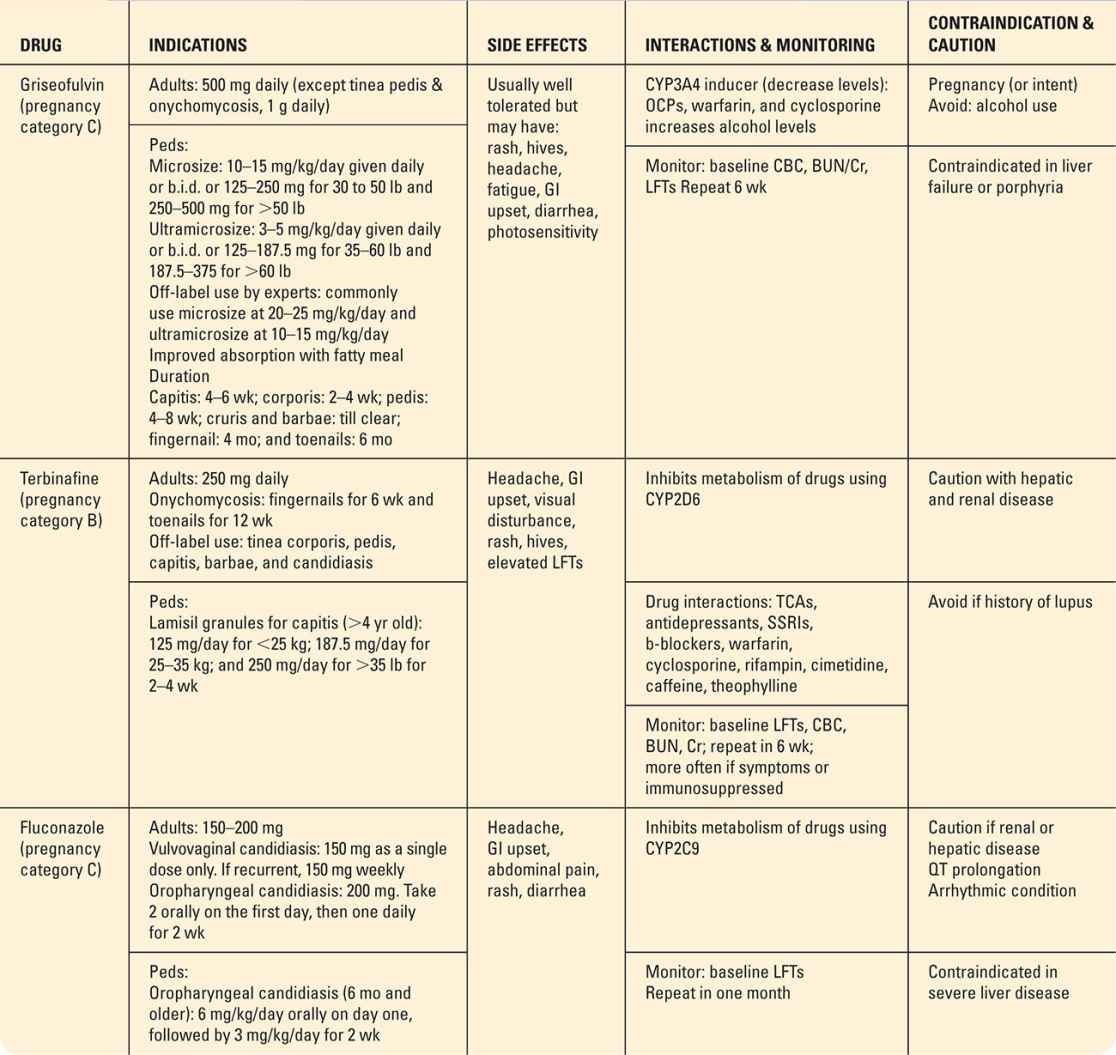

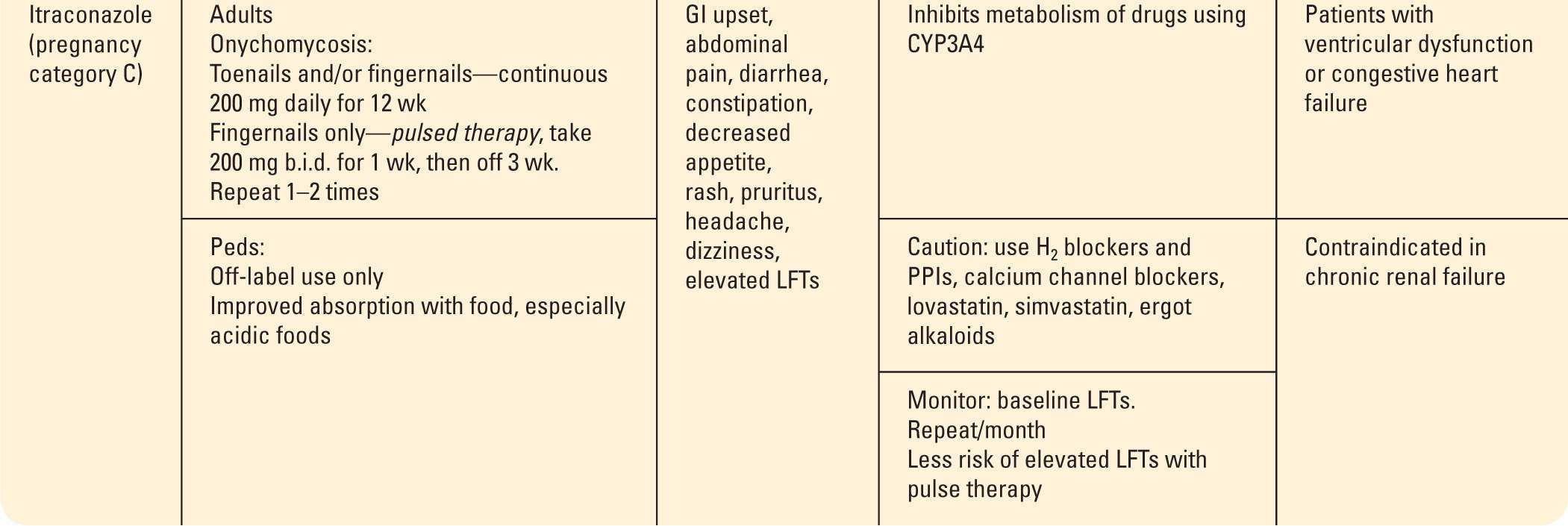

Griseofulvin was the first systemic antifungal used for the treatment of superficial fungal infections of the hair, skin, and nails. Although effective, newer agents have improved bioavailability and absorption, resulting in greater efficacy and shorter duration of therapy. The most common oral antifungals include terbinafine (Lamisil) from the allylamine group, and fluconazole (Diflucan) and itraconazole (Sporanox) both from the azole group. Newer antifungals reach the layers of the stratum corneum faster and are retained longer, resulting in higher cure rates, compared with that of griseofulvin.

Antifungals also vary in their detectable levels present in the eccrine or sweat glands. Itraconazole can be detected in the eccrine sweat glands within 24 hours and is excreted into the sebum, which explains why it is commonly used off-label for tinea versicolor. Systemic treatment for onychomycoses is also advantageous as terbinafine stays in the nail for about 30 weeks after therapy, while fluconazole (off-label) and itraconazole continue for 6 and 12 months, respectively. So once therapy is completed, drug levels remain present in the toenails and fingernails to improve the mycotic cure rate.

When considering oral antifungal therapy, a careful review of the patient’s comorbidities, as well as medications, is critical. Metabolism of antifungals occurs through the cytochrome P450 system and therefore can affect the metabolism of the antifungal or patient’s other medications. Patients with liver or renal disease and the elderly may not be good candidates for oral antifungal therapy. Patient lifestyle, including use of alcohol, should be discussed, as well as the need for monitoring. The risk of interactions, adverse events, monitoring, and contraindications are listed in Table 12-2.

Systemic Antifungal Agents for Treatment of Superficial Cutaneous Fungal Infections |

Note: In 2013, the FDA advised limited use of systemic ketoconazole in view of liver injury, adrenal gland problems, and drug interactions. Oral ketoconazole should not be used for mucocutaneous infections or first-line treatment for any mycotic infection unless it is life-threatening or alternative therapy is not tolerated or available. There are many off-label uses of systemic antifungals that can be safe and effective treatments for dermatophyte and yeast infections. Primary care providers should understand the risks, benefits, and efficacy of off-labeled prescribing, or refer recalcitrant or severe cases to dermatology.

This text will not review the systemic use of ketoconazole (azole) as its use in dermatology has become very limited. Historically, oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) has been used off-label for many years for treatment of benign mucocutaneous infections such as tinea versicolor. In 2013, the FDA warned that oral ketoconazole should not be used for dermatophyte infections or as first-line treatment for any mycotic infection in view of the risk of liver injury, adrenal problems, and drug interactions. Thus far, these risks have not been associated with topical ketoconazole, which continues to be FDA indicated for treatment of dandruff, candidiasis of the skin, tinea versicolor or Pityrosporum, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea infections.

DERMATOPHYTES

Pathophysiology

Dermatophytes are a group of fungi comprising three genera: Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton. Dermatophyte infections are commonly called tinea or ringworm, given their annular or serpiginous border in the presenting lesions. Some patients misunderstand and worry that there may actually be worms in their skin; so it is advantageous to teach patients about the true etiology. Unlike Candida, dermatophytes can survive only in the stratum corneum (top layer) of the skin, hair, and nails, and not on mucosal surfaces such as the mouth or vaginal mucosa. Subtypes of tinea are classified by the area of the body infected or the pathogen responsible for the infection.

The majority of tinea infections are caused by T. rubrum, with the exception of tinea capitis. T. tonsurans is the most common causative organism of capitis in the United States, while M. canis is the most common worldwide. Transmission occurs from direct contact with an infected host, which may be human to human (anthropophilic), animal to human (zoophilic), or soil to human (geophilic). Dermatophytes can survive on exfoliated skin or hair, and live on moist surfaces in the environment such as showers or pools, bedding, clothing, combs, and hats for 12 to 15 months. Once exposed, the incubation time to symptoms is usually 1 to 2 weeks. Clinicians should keep this in mind when dealing with community outbreaks of tinea.

Generally, tinea occurs in the adolescent and adult population, except for tinea capitis, seen mostly in children between the ages of 3 and 7 years. Healthy people may become infected, but there are several host and environmental factors that predispose someone to dermatophyte infections. People on topical and systemic corticosteroids or with suppressed immune systems are more susceptible. Crowded living conditions, poor hygiene, high humidity, athletes in contact sports (i.e., wrestling), or close contact with infected persons, animal, or soil can increase one’s risk for infection. Studies suggest that individuals may have a genetic predisposition to particular strains of dermatophytes among members of the same household.

Subtypes of Tinea

Tinea pedis

Athlete’s foot or tinea pedis is the most common disease affecting the feet and toes. It can present with a variety of symptoms depending on the causative organism and may include pruritus, inflammation, scale, vesicles, bullae, or may sometimes be asymptomatic. The most common pathogens are T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and E. floccosum. Tinea pedis is transmitted by direct contact with contaminated shoes or socks, showers, locker rooms, and pool surfaces, where the organism can thrive. It is very contagious and can lead to household outbreaks or recurrence of the infection. Chronic tinea pedis can lead to fungal infections of the toenails, secondary bacterial infections, or entry of organisms that can cause cellulitis of the lower legs. These disease complications are important to consider in the management of diabetic, immunocompromised, and elderly patients. There are four types of tinea pedis affecting the feet and toes:

• Moccasin type involves one or both heels, soles, and lateral borders of the foot, presenting as well-demarcated hyperkeratosis, fine white scale, and erythema (Figure 12-1). The pathogens are commonly T. rubrum or E. floccosum. This type is chronic and very recalcitrant to therapy.

• Interdigital type involves infection of the web spaces and can cause very different symptoms of erythema and scaliness, or maceration and fissures. The third and fourth web spaces are most commonly involved and are at risk to develop a secondary bacterial infection (Figure 12-2). Obtaining a KOH from the macerated area can be difficult and may require bacterial cultures. The causative organisms are usually T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and E. floccosum.

• Inflammatory/vesicular involves a vesicular or bullous eruption often caused by T. mentagrophytes and involves the medial aspect of the foot (Figure 12-3).

• Ulcerative type presents with erosions or ulcers in the web spaces. T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and E. floccosum are common pathogens, with frequent secondary bacterial infections in diabetic or immunocompromised patients.

FIG. 12-1. Mocassin-type tinea pedis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Tinea pedis |

• Psoriasis

• Dermatitis (contact and dyshidrotic)

• Pitted keratolysis

• Bacterial infections

• Erythrasma

• Bullous disease

Management

Hyperkeratosis, which may accompany tinea pedis, should be treated with a keratolytic agent to allow for better penetration of the antifungal as it softens and thins the keratin layer. Topical preparations such as lactic acid, ammonium lactate, or salicylic acid are available in a variety of formulations as both prescription and over-the-counter treatment. If vesicles are present, Burow solution (13% aluminum acetate) can be used for anti-itch, astringent, and antibacterial properties. It is available over the counter, both as Domeboro or generic, and is applied as wet compresses four times daily. Topical antifungals should be applied immediately following the compresses for maximum penetration.

FIG. 12-2. Interdigital tinea pedis with maceration.

FIG. 12-3. Inflammatory vesicular tinea pedis.

Interdigital maceration can be treated with aluminum chloride hexahydrate 20% (Drysol, Hypercare) twice daily to provide an antibacterial and drying effect. The broad-spectrum activity of the topical azoles, especially econazole and sertaconazole, is a good choice for interdigital maceration often involving secondary bacterial infections. Moisture-wicking socks or a change in socks or shoes midday can help decrease prolonged periods of moisture of the feet.

Systemic antifungals are often necessary for extensive moccasin-type tinea pedis or when topical treatment has failed. Terbinafine and itraconazole are more effective than griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea pedis.

Tinea cruris

Often referred to as “jock itch,” tinea cruris is a dermatophyte infection of the groin but may also affect inner thighs and buttocks, and presents with well-demarcated erythematous or tan plaques with raised scaly borders or advancing edge (Figure 12-4). There may be vesicles present on the border with severe inflammation and pruritus as a complaint. Clinicians should also inspect the feet of patients diagnosed with cruris as spores can be transmitted when patients are putting on their underwear. It is helpful to have patients put on their socks first before putting on their underwear.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Tinea cruris |

• Erythrasma

• Inverse psoriasis

• Seborrheic dermatitis

• Intertrigo

• Candidiasis

• Hailey–Hailey disease

FIG. 12-4. Tinea cruris. Advancing border with scale (arrow).

Management

Tinea cruris responds to any of the topical antifungals, with the allylamines being more effective. Antifungals should be applied for 2 to 4 weeks until clear, and then one week longer. In a culture proven tinea, if the infection does not clear within the expected time period, treatment should be changed to another class of topical antifungal or to a systemic agent. Eruptions not responding to therapy should prompt a KOH test and culture if these had not been done or a reconsideration of the diagnosis of tinea.

Tinea corporis

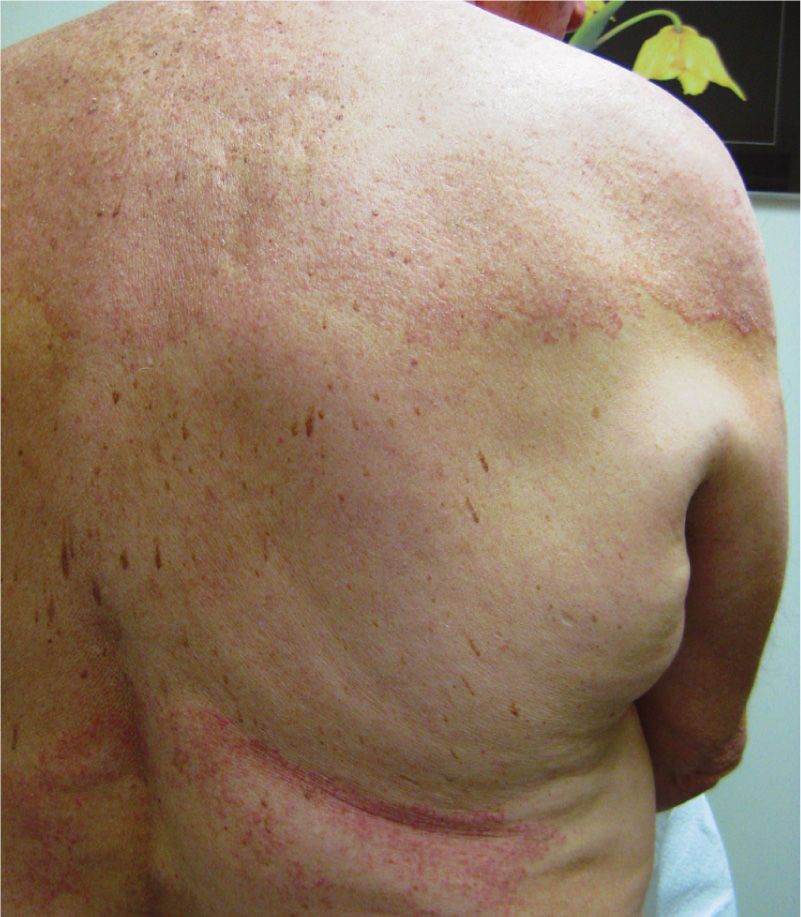

Ringworm or tinea corporis is a dermatophyte infection (T. rubrum most common pathogen) involving areas of the trunk and extremities, not including the groin and palms. It presents as pruritic, erythematous, scaly macules or papules that expand outward to form classic annular or arciform lesions with a raised and sometimes a vesicular advancing border (Figure 12-5). The central area flattens and turns from red to brown as the border broadens. The lesions may fuse, producing large gyrate patterns, and include large body surface areas (Figures 12-6 and 12-7).

A clinical variant of tinea corporis is Majocchi granuloma, and involves the invasion of the dermatophyte into the hair follicles. The characteristic lesions are erythematous, perifollicular papules and pustules. It commonly occurs on the legs of young women from shaving, but can be seen in men and children in other hair-bearing areas. Immunocompromised patients may have a more nodular presentation.

FIG. 12-5. Tinea corporis. The scaly border is potassium hydroxide positive.

FIG. 12-6. Tinea corporis with gyrate lesions forming.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Tinea corporis |

• Dermatitis (nummular, atopic, contact, etc.)

• Psoriasis

• Pityriasis rosea

• Tinea versicolor

• Annular erythemas

• Subacute lupus erythematosus

• Granuloma annulare

• Mycosis fungoides

Management

Tinea involving small body surface areas usually responds quickly to topical therapy, especially from the newer agents in the allylamine and benzylamine groups. Systemic antifungals should be considered if the patient is immunocompromised, eruption involves large body surface areas, tinea is not responsive to topical therapy, or dermatophyte infection is a Majocchi granuloma. Terbinafine is a good agent for systemic therapy and is well tolerated by both children and adults. A topical antifungal may be used in conjunction with oral therapy. Skin eruptions diagnosed as tinea corporis that do not respond to antifungals, or are recurrent, should be reevaluated (Figure 12-7).

Tinea manuum

Tinea manuum is a dermatophyte infection of the dorsal hand, palm, or interdigital spaces. Because of the lack of sebaceous glands on the palm, it can have two different clinical presentations. Patients with palmar involvement have symptoms similar to those of moccasin-type tinea pedis, with erythema, hyperkeratosis, and fine scaling in palmar creases. Patients often think their hand is just very dry and have no idea it is an infection. You may find patients with “two feet, one hand” syndrome, with tinea presenting in both feet and one hand—usually the hand/fingers that pick their feet or toenail fissures (Figure 12-8). Tinea manuum on the dorsum of the hand has a more annular presentation similar to tinea corporis. For this reason, it is important to examine the dorsum of the hands and feet, as well as the nails that may be involved.

FIG. 12-7. Tinea corporis large, diffuse areas. Includes differential diagnosis eczema, CTCL mycosis fungoides, dermatomyositis, and psoriasis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Tinea manuum |