Superficial Chemical Peels

Pearl E. Grimes

Marta I. Rendon

Juan Pellerano

The ancient Egyptians were among the first civilizations in recorded history to use chemicals as exfoliating agents for aesthetic purposes. They used alabaster, animal oils, and salt.1,2 The Greeks and Romans used pumice, myrrh, frankincense, mustard, and sulfur for lightening the skin and improvement of wrinkles. Early reports of chemical peeling in Europe were described by Fox, Hebra, and Unna.3,4 In 1882, Unna described his experiences using a variety of peeling agents, including resorcinol, phenol, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and salicylic acid. The experiences of the aforementioned dermatologists pioneered the use of chemical peels in dermatology.

Chemical peeling or chemical exfoliation is a form of skin resurfacing whereby exfoliating chemical agents are applied to the skin surface to induce epidermal and/or dermal injury/destruction. Peeling agents induce controlled wounding of the skin followed by organized repair. The desired outcome of peeling procedures is generation of a new epidermis and dermal collagen remodeling. Dyschromias, photodamage, and rhytides are often improved.

In 1982, Stegman reported the histologic effects of three peeling agents, including TCA, full-strength phenol, Baker’s phenol, and dermabrasion on normal and sun-damaged skin of the neck.5 This study demonstrated that 40% to 60% TCA caused epidermal necrosis, papillary dermal edema, and homogenization to the midreticular dermis 3 days after peeling. Findings were similar in sun-damaged compared with non–sun-damaged skin. Ninety days after peeling, Stegman observed an expanded papillary dermis, which he defined as the Grenz zone. The thickness of the Grenz zone increased as the depth of peeling increased. The investigative work of Stegman and others facilitated our understanding of the capacity of medium-depth and deep peeling agents to restore epidermal and dermal order.

Others have assessed the histologic and ultrastructural changes of chemical peeling. Nelson et al.6 assessed the effects of a combination Jessner’s solution and 35% TCA peel. Biopsies were performed at baseline, 2 weeks, and 3 months. Type I collagen increased after peeling. Ultrastructural features of the skin after peeling included markedly decreased epidermal intracytoplasmic vacuoles, decreased elastic fibers, and increased activated fibroblasts. These data further substantiated the effects of chemical peeling agents for improvement of photodamage and rhytides.

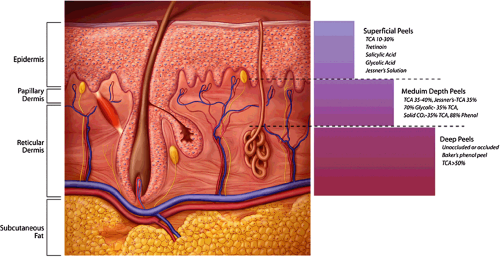

Chemical peeling agents are classified as superficial, medium-depth, or deep peels.7 Superficial peels target the stratum corneum to the papillary dermis (Fig. 17-1). They include glycolic acid, salicylic acid, Jessner’s solution, tretinoin, and TCA in concentrations of 10% to 30%. Medium-depth peels penetrate to the upper reticular dermis and include TCA (35%–50%), combination glycolic acid 70%/TCA 35%, Jessner’s/TCA 35%, and phenol 88%. Deep chemical peels utilize the Baker-Gordon formula and penetrate to the midreticular dermis. The depth of the chemical peel determines the efficacy, outcome, and safety of the procedure.

Indications for Chemical Peeling in Darker Skin Types

Dark skin demonstrates significantly greater intrinsic photoprotection because of the increased content of epidermal melanin (see Chapter 2). Clinical photodamage, actinic keratoses, rhytides, and skin malignancies are less common problems in deeply pigmented skin. However, darker skin types are frequently plagued with dyschromias because of the labile responses of cutaneous melanocytes in deeply pigmented individuals (see Chapter 2). Despite major concerns regarding peel complications such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and scarring in darker racial ethnic groups, recent studies suggest that peeling procedures, particularly superficial peeling, can be safely performed in darker skin.

Hence, peel indications differ between light and dark skin (Table 17-1). Key indications in Fitzpatrick’s skin types I, II, and III include photodamage, rhytides, acne, scarring, and the dyschromias characterized by hyperpigmentation. In contrast, key indications in darker skin types include disorders of hyperpigmentation, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, acne, pseudofolliculitis barbae, textural changes, oily skin and wrinkles, and photodamage.

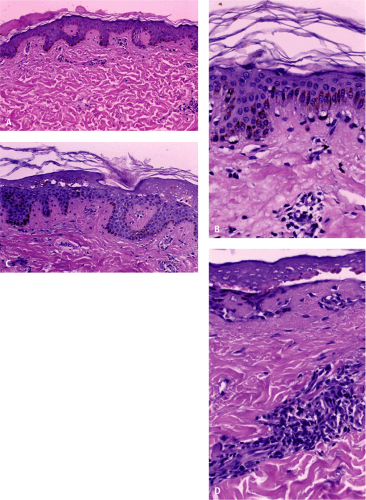

Grimes8 compared the histologic alterations induced by a variety of chemical peels in 17 patients with skin types IV, V, and VI, including glycolic acid 70%, salicylic acid 30%, Jessner’s solution, and 25% and 30% TCA. Peels were applied to 4 X 4–cm areas of the back and 2 X 2–cm postauricular sites. Biopsies were performed at 24 hours (Fig. 17-2A–D). Glycolic acid induced the most significant stratum corneum necrosis. Compared with the other tested peels, salicylic acid and Jessner’s peels caused mild lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrates. The most severe damage was induced by 25% and 30% TCA, which caused deep epidermal necrosis and dense papillary dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrates. TCA test sites developed postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. These findings corroborate our clinical experience using these agents. In general, glycolic, salicylic acid, and Jessner’s peels induce a lower frequency of postpeeling complications compared with 25% and 30% superficial TCA peels.

Figure 17-1 Cross section of skin illustrating the depth of wounding caused by chemical peeling agents. |

Table 17-1 Chemical peel indications in skin types I–III versus skin types IV–VI | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General Considerations for Patient Preparation

Peel preparation varies with the condition being treated. Regimens differ for photodamage, hyperpigmentation (melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation), acne vulgaris, and other conditions. In addition, there are special issues to be considered when treating darker racial ethnic groups. A detailed history and cutaneous examination should be performed in all patients before chemical peeling. Standardized photographs are taken of the areas to be peeled, including full-face frontal and lateral views.

Use of topical retinoids (tretinoin, tazarotene, retinol formulations) for 2 to 6 weeks before peeling thin the stratum corneum and enhance epidermal turnover. Such agents also reduce the content of epidermal melanin and

expedite epidermal healing. Retinoids also enhance the penetration and depth of chemical peeling. Optimal effects are demonstrated with these agents when treating photodamage in Fitzpatrick skin types I to III. They can be used until 1 or 2 days before peeling. Retinoids can be resumed postoperatively after all evidence of peeling and desquamation subsides.

expedite epidermal healing. Retinoids also enhance the penetration and depth of chemical peeling. Optimal effects are demonstrated with these agents when treating photodamage in Fitzpatrick skin types I to III. They can be used until 1 or 2 days before peeling. Retinoids can be resumed postoperatively after all evidence of peeling and desquamation subsides.

In contrast to photodamage, when treating conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, retinoids should either be discontinued 1 or 2 weeks before peeling or completely eliminated from the peeling prep to avoid postpeel complications, such as excessive erythema, desquamation, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. These conditions are more common in darker

racial ethnic groups, populations at greater risk for postpeel complications. Similar precautions should be taken in acne patients with darker skin types (V and VI).

racial ethnic groups, populations at greater risk for postpeel complications. Similar precautions should be taken in acne patients with darker skin types (V and VI).

Topical alpha hydroxy acid or polyhydroxy acid formulations can also be used to prep the skin. In general, they are less aggressive agents in affecting peel outcomes. The skin is usually prepped for 2 to 4 weeks with a formulation of hydroquinone 4% or higher compounded formulations (5%–10%) to reduce epidermal melanin. This is extremely important when treating the aforementioned dyschromias. Although less effective, other topical bleaching agents include azelaic acid, kojic acid, arbutin, and licorice. Patients can also resume use of topical bleaching agents postoperatively after peeling, and irritation subsides. Broad-spectrum sunscreens (UVA and UVB) should be worn daily.

A flare of herpes following a superficial chemical peel is rare. Hence, pretreatment with antiviral therapy is usually not indicated. However, one can prophylactically treat with antiviral therapies including valacyclovir 500 mg twice a day, famciclovir 500 mg twice a day, or acyclovir 400 mg twice a day for 7 to 10 days beginning 1 or 2 days before the procedure.

Glycolic Acid Peels

Alpha hydroxy acid (AHA) peels have been shown to improve the skin surface by thinning the stratum corneum, promoting epidermolysis, dispersing basal layer melanin, and increasing collagen synthesis within the dermis9 (Fig. 17-3). The most common AHAs used as peeling agents are glycolic acid, lactic acid, mandelic acid, and, recently, pyruvic acid. Glycolic acid peels decrease hyperpigmentation through a wounding and re-epithelization process. Glycolic acid is the best-known superficial peeling agent, having been used in clinical practice since the 1800s. It is part of the family of alpha hydroxy acids, which occur naturally in foods. Glycolic acid is used in strengths ranging from 20% to 70% to treat a variety of defects of the epidermis and papillary dermis on almost any area of the body.

Moy et al.10 assessed the efficacy of several commonly used peeling agents, including glycolic acid in a mini pig model. The chemical peels were applied in different concentrations to 2 cm X 2 cm patches and left on the skin for 15 minutes. The following concentrations were used: phenol-Bakers, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 88%; TCA, 25%, 50%, 75%; glycolic acid, 50%, 70%; and pyruvic acid, 50%, 100%. Biopsies were taken from each site at 1, 7, and 21 days postpeel and evaluated for epidermal changes, inflammation, and collagen deposition. The Baker phenol peel caused the most inflammation and nonspecific reaction but also a large amount of new collagen deposition. At 1 day postpeel, larger concentrations of phenol and TCA caused the most epidermal sloughing and inflammation. The extent of the reaction was directly proportional to collagen deposition at 21 days.10 Although the authors concluded that glycolic acid and pyruvic acid caused the least nonspecific reaction, they found the resulting collagen deposition to be disproportionately large. These findings suggest a direct stimulatory effect by the two acids on collagen production.

Another study assessed the damage and recovery of skin barrier function after glycolic acid chemical peeling and crystal microdermabrasion.9 Noninvasive bioengineering methods were used in the study. Superficial chemical peeling was conducted with 30%, 50%, and 70% glycolic acid and aluminum oxide crystal microdermabrasion on the forearms of 13 women. Skin response was measured by visual observation and use of an evaporimeter, corneometer, and colorimeter at set intervals before and after peeling. Results of this study suggest that the skin barrier function is damaged by glycolic acid peeling and aluminum oxide crystal microdermabrasion but recovers within 1 to 4 days. Therefore, repeating the superficial peeling procedure at 2-week intervals will allow sufficient time for the damaged skin to recover its barrier function.

Glycolic acid formulations

Glycolic acid peeling agents include buffered, partially neutralized, and esterified formulations. Generally, peeling strengths range from 20% to 70%. The efficacy of glycolic peels can depend on the pH, strength, and time of application. Unbuffered formulations with low pH have the potential to induce greater epidermal and dermal damage.

Indications

Glycolic peels can be used on all body areas and Fitzpatrick skin types. The main symptoms of skin types IV to VI are dyschromias, including melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation from acne or burns. Other indications are photodamage, rosacea, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.11,12

Several studies were conducted to evaluate whether a series of glycolic acid peels would provide improvement in dark-skinned patients when combined with topical regimens, such as hydroquinone, tretinoin, or topical steroids.

Sarkar et al.13 assessed the efficacy of a series of glycolic acid peels when combined with a topical bleaching agent compared with use of the bleaching formula alone in a series of dark-skinned patients with melasma. The authors compared the efficacy of serial glycolic acid peeling with a series three 30% glycolic peels and three 40% peels in combination with the modified Kligman bleaching formulation (hydroquinone 5%, hydrocortisone acetate 1%, and tretinoin 0.05%) and with the bleaching formula alone. Forty women were included in each group.

Both groups showed a statistically significant improvement in the Melasma Area Severity Index (MASI) score at 21 weeks. However, maximal improvement occurred in the group treated with the series of glycolic acid peels in combination with the topical bleaching regimen.

Both groups showed a statistically significant improvement in the Melasma Area Severity Index (MASI) score at 21 weeks. However, maximal improvement occurred in the group treated with the series of glycolic acid peels in combination with the topical bleaching regimen.

An 8-week, split-face study of 21 Hispanic women with bilateral epidermal and mixed melasma found no significant difference between combination therapy using glycolic acid peels plus a topical regimen of hydroquinone compared with hydroquinone alone.14 Patients underwent a glycolic acid peel every 2 weeks plus topical hydroquinone 4% twice daily. Only hydroquinone 4% was applied daily to the opposite side of the face. Both groups showed significant reduction in skin pigmentation compared with baseline. Unfortunately, these two studies used different measurement devices, product concentrations, and frequency of peels. This might explain the differences in results. In our experience, we have noted that the addition of glycolic acid peels to any hyperpigmentation regimen usually accelerates the rate of improvement as well as improves the tone, texture, and color of the skin (Fig. 17-4A,B and Fig. 17-5A,B).

A series of 10 Asian women with melasma and fine wrinkles were treated with 2% hydroquinone and 10% glycolic acid applied to both sides of the face.15 A series of 20% to 70% glycolic peels were performed on one side for comparison. Greater improvement with minimal side effects were noted on the side treated with glycolic acid peels. In another study, 40 Asian patients with moderate to moderately severe acne were treated with a series of 35% to 70% glycolic acid peels.16 The investigators noted significant improvement in skin texture and acne. Side effects were reported in 5.6% of patients.

Nineteen black patients with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation were treated with glycolic acid peeling.17 The control group was treated with 2% hydroquinone/10% glycolic acid twice a day and tretinoin 0.05% at bedtime, whereas the active peel group received the same topical regimen plus a series of six serial glycolic acid peels. Although not statistically significant, greater improvement was noted in the chemical peel group.

The safety and efficacy of a series of glycolic acid facial peels were investigated in 25 Indian women with melasma.18 Patients were treated with 50% glycolic acid peels monthly for 3 months. Improvement was noted in 91% of patients with maximal clearing occurring in patients classified with epidermal melasma. Side effects were observed in one patient who developed brow hyperpigmentation.

Figure 17-4 Patient with melasma treated with triple combination bleaching agent (Tri-Luma) and a series of glycolic acid peels. A: Before. B: After. |

In patients with photodamage, AHA peels and topical products may be combined with retinoids and other antioxidants for maximum benefit. The synergistic effects of fluorouracil and glycolic acid have been observed in the treatment of actinic keratoses. For patients with melasma, AHA peels and combination products containing bleaching agents such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, and glycolic

acid have increased efficacy. Dark-skinned patients with acne, mild acne scarring, rosacea, and rhytids can obtain results with antibacterial agents and topical retinoids supplemented with AHA peels and lotions.19

acid have increased efficacy. Dark-skinned patients with acne, mild acne scarring, rosacea, and rhytids can obtain results with antibacterial agents and topical retinoids supplemented with AHA peels and lotions.19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree