Fig. 28.1

Cross sections of a lymphedematous (right) and a normal arm (left) showing abundance of excess adipose tissue in the affected arm. Courtesy of Dr. C.H. Håkansson, Department of Oncology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund (the author has rights to use image with permission)

Presently there is no cure for lymphedema. With early diagnosis, the majority of patients can be treated by conservative treatment, such as complex decongestive therapy (CDT) [13], which comprises manual lymph drainage, compression therapy, physical exercise, skin care and self-management, followed by wearing flat knitted compression garments. The effect of CDT on long-standing massive edema with excess adipose tissue is poor, since adipose tissue does not disappear by means of compression alone. In addition, surgical intervention is reserved for patients with excess volume and heaviness causing severe strain in the shoulder and neck, functional impairment, recurrent attacks of erysipelas, and problems with clothing fit.

For the treatment of late-stage lymphedema that does not respond to conservative treatment, liposuction combined with postoperative, lifelong effective compression therapy has become a viable alternative. Postoperative follow-up and regular adjustment of the compression technology is mandatory.

There are various possible explanations for the adipose tissue hypertrophy. There is a physiological imbalance of blood flow and lymphatic drainage, resulting in the impaired clearance of lipids and their uptake by macrophages [14]. However, there is increasing support, for the view that the fat cell is not simply a container of fat, but is an endocrine organ and a cytokine-activated cell [15, 16] and that chronic inflammation plays a role here [15, 17]. The same pathophysiology applies for primary and secondary leg lymphedema. Recent research showed a relationship between slow lymph flow and adiposity, as well as that between structural changes in the lymphatic system and adiposity [18, 19].

From a more clinical view, other indications for adipose tissue hypertrophy have been found:

Consecutive analyses of the content of the aspirate by the author, removed under bloodless conditions using a tourniquet, showed a very high content of adipose tissue in 44 women with post-mastectomy arm lymphedema (mean 90 %, range 58–100) [20]. This has been confirmed by Damstra et al.’s [21] study of 37 patients with end-stage breast cancer related lymphedema where the proportion of fat in the aspirate (when a tourniquet was used) was 93 % (range 59–100 %). The same outcome was shown in a study by Schaverien et al. in 12 patients with arm lymphedema following breast cancer treatment with 92 % (range, 75–100) of fat in the aspirate [22].

Analyses with dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in 18 women with arm lymphedema following a mastectomy showed a significant increase of adipose (73 %) and muscle tissue (47 %), and even bone mineral content (7 %) in the non-pitting swollen arm before surgery. The greater weight of the affected arm leads to a higher mechanical load on both the muscle and the skeleton, resulting in increased muscle and bone mass. There was no correlation between the duration of lymphedema and the amount of excess adipose, muscle, or bone tissue. This indicates that the increase in soft tissue volume develops when the lymphedema appears or soon thereafter [23].

Preoperative investigation with volume-rendered computer tomography (VRCT) in 11 women showed a significant preoperative increase of adipose tissue in the swollen arm, the excess volume consisting of 81 % (range 68–96) fat [24].

Tonometry findings in 20 women with post-mastectomy arm lymphedema showed postoperative changes in the upper arm, but not in the forearm, which also showed significantly higher absolute values than in the upper arm. This is probably caused by the high adipose tissue content with little or no free fluid, as in the normal arm. The thinner subcutaneous tissue in the forearm may also play a part [25].

The findings of increased adipose tissue in intestinal segments in patients with Crohn’s disease, known as “fat wrapping,” have clearly shown that inflammation plays an important role [17, 26, 27].

A major problem in Graves’s ophthalmopathy is an increase in the intraorbital adipose tissue volume leading to exophthalmos. Overexpression of adipocyte-related immediate early genes in active ophthalmopathy and cysteine-rich, angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61) may have a role in both orbital inflammation and adipogenesis and serve as a marker of disease activity [28].

The common understanding among clinicians is that the swelling of a lymphedematous extremity is due purely to the accumulation of lymph fluid, which can be removed by use of noninvasive conservative regimens such as CDT.

Microsurgery and lympho-venous anastomosis (LVA) have been studied for a long time without convincing results [31]. Although the LVA has been performed and studied for more than three decades, this method still has not had a breakthrough and will never become a treatment of choice in daily practice. In a large overview article by Campisi et al. [32], a positive effect was described in early stages of lymphedema. However, for later, more irreversible stages, this therapeutic option was not suitable. Moreover, a recent study showed that the net effect of LVA was minor and that the outcome was due to the CDT performed preoperatively and postoperatively [33].

Brorson et al. [12] concluded that when the excess volume is dominated by adipose tissue, supra-facial clearance by liposuction is the only method to achieve up to 100 % excess volume reduction.

Today, chronic non-pitting arm lymphedema of up to 4 l in excess can be effectively removed by use of liposuction and compression therapy, without any further reduction in lymph transport [34]. Long-term results, up to 15 years, have not shown any recurrence of the arm swelling. Complete reduction is mostly achieved in between 3 and 6 months, often earlier (see Figs. 28.2 and 28.3) [12, 35].

Fig. 28.2

(a) A 74-year-old woman with a non-pitting arm lymphedema for 15 years. Preoperative excess volume was 3,090 ml. © Håkan Brorson. (b) Postoperative result. © Håkan Brorson

Fig. 28.3

Mean (±SEM) postoperative excess volume reduction in 116 women with arm lymphedema following breast cancer. © Håkan Brorson

In 2009 Damstra et al. [21] reproduced these results in a large study with 37 breast cancer-related lymphedema patients. A recent publication from 2012 with a 5-year follow-up in 12 patients with breast cancer related lymphedema confirmed no recurrence with this technique [22]. Promising results can also be achieved for leg lymphedema, for which complete reduction is usually reached at around 6 months (see Figs. 28.4a, b) [36, 37].

Fig. 28.4

(a) Secondary lymphedema: Preoperative excess volume 7,070 ml (left). Postoperative result after 6 months where excess volume is –445 ml, i.e., the treated leg is somewhat smaller than the normal one (right). © Håkan Brorson. (b) Primary lymphedema: Preoperative excess volume 6,630 ml (left). Postoperative result after 2 years where excess volume is 30 ml (right). © Håkan Brorson

Liposuction

Surgical Technique

Made-to-measure compression garments (two sleeves and two gloves) are measured and ordered 2 weeks before surgery, using the healthy arm and hand as a template. Nowadays we use power-assisted liposuction because the vibrating cannula facilitates the liposuction, especially in the leg, which is more demanding to treat. Initially the “dry technique” was used [38]. Later, to minimize blood loss, a tourniquet was utilized in combination with tumescence, which involves infiltration of 1–2 l of saline containing low-dose adrenaline and lignocaine [39, 40].

Through approximately 10–15, 3-mm-long incisions, liposuction is performed using 15- and 25-cm-long cannulas with diameters of 3 and 4 mm (see Figs. 28.5 and 28.6). Liposuction is executed circumferentially, step-by-step from wrist to shoulder, and the hypertrophied fat is removed as completely as possible (see Figs. 28.5, 28.6, and 28.7).

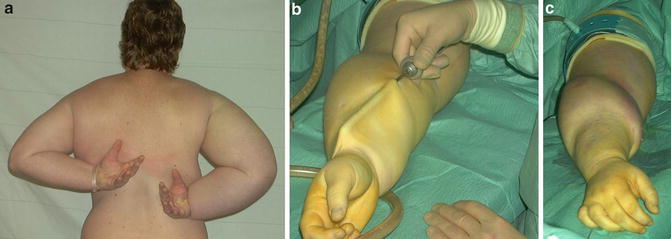

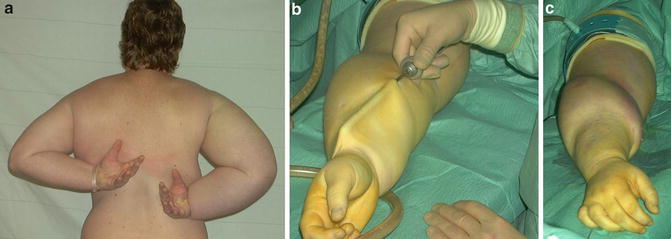

Fig. 28.5

Liposuction of arm lymphedema. The procedure takes about 2 h. From preoperative to postoperative state (left to right). Note the tourniquet, which has been removed at the right, and the concomitant reactive hyperemia. © Håkan Brorson

Fig. 28.6

(a) Preoperative picture showing a patient with a large lymphedema (2,865 ml) and decreased mobility of the right arm. © Håkan Brorson. (b) The cannula lifts the loose skin of the treated forearm. (c) The distal half of the forearm has been treated. Note the sharp border between treated (distal forearm) and untreated (proximal arm) area. © Håkan Brorson

Fig. 28.7

The aspirate contains 90–100 % adipose tissue in general. This picture shows the aspirate collected from the lymphedematous arm of the patient shown in Figs. 28.4, 28.5, and 28.7 before removal of the tourniquet. The aspirate sediments into an upper adipose fraction (90 %) and a lower fluid (lymph) fraction (10 %). © Håkan Brorson

When the arm distal to the tourniquet has been treated, a sterilized made-to-measure compression sleeve is applied (Jobst¨ Elvarex BSN medical, compression class 2) to the arm to stem bleeding and reduce postoperative edema. A sterilized, standard interim glove (Cicatrex interim, Thuasne¨, France) in which the tips of the fingers have been cut to facilitate gripping, is put on the hand. The tourniquet is removed and the most proximal part of the upper arm is treated using the tumescent technique [39, 40]. Finally, the proximal part of the compression sleeve is pulled up to compress the proximal part of the upper arm. The incisions are left open to drain through the sleeve. The arm is lightly wrapped with a large absorbent compress covering the whole arm (60 × 60 cm, Cover-Dri, www.attends.co.uk). The arm is kept at heart level on a large pillow. The compress is changed when needed.

The following day, a standard gauntlet (i.e., a glove without fingers, but with a thumb; Jobst Elvarex compression class 2) is put over the interim glove after the thumb of the gauntlet has been cut off to ease the pressure on the thumb. If the gauntlet is put on straight after surgery, it can exert too much pressure on the hand when the patient is still not able to move the fingers after the anesthesia. Operating time is, on average, 2 h. An isoxazolylpenicillin or a cephalosporin is given intravenously for the first 24 h and then in tablet form until incisions are healed, about 10–14 days after surgery. Liposuction technique for leg lymphedema is similar to that for the arm.

Postoperative Care

Garments are removed 2 days postoperatively so that the patient can take a shower. Then, the other set of garments is put on and the used set is washed and dried. The patient repeats this after another 2 days before discharge. The standard glove and gauntlet is usually changed to the made-to-measure glove at the end of the hospital stay (Fig. 28.8).

Fig. 28.8

The compression garment is removed two days after surgery so that the patient can take a shower. When bandages are used, at the first bandage change, made-to-measure, flat knitted garment are measured and ordered. Then, the other set of garments is put on and the used set is washed and dried or the arm is re-bandaged. A significant reduction of the right arm has been achieved, as compared with the preoperative condition seen in Fig. 28.6a. © Håkan Brorson

The patient alternates between the two sets of garments (1 set = 1 sleeve and 1 glove) during the 2 weeks postoperatively, changing them daily or every other day so that a clean set is always put on after showering and lubricating the arm. After the 2-week control, the garments are changed every day after being washed. Washing “activates” the garment by increasing the compression due to shrinkage.

Controlled Compression Therapy (CCT)

A prerequisite to maintaining the effect of liposuction and, for that matter, conservative treatment, is the continuous use of a compression garment [12]. Compression therapy is crucial, and its application is therefore thoroughly described and discussed at the first clinical evaluation. If the patient has any doubts about continued CCT, she is not accepted for treatment. After initiating compression therapy, the custom-made garment is taken in, when needed, at each visit using a sewing machine, to compensate for reduced elasticity and reduced arm volume.

This is most important during the first 3 months when the most notable changes in volume occur. At the 1- and 3-month visits, the arm is measured for new custom-made garments (two sets). This procedure is repeated at 6, (9), and 12 months. If complete reduction has been achieved at 6 months, the 9-month control may be omitted. If this is the case, remember to prescribe garments for 6 months, which normally means double the amount than would be needed for 3 months. It is important, however, to take in the garment repeatedly to compensate for wear and tear.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree