Fig. 29.1

Injection of lymphazurin blue or other dyes can visualize dermal and subcutaneous lymphatics. This method of mapping assists in the identification of feeding lymphatics which sustain and increase the volume of a lymphocele

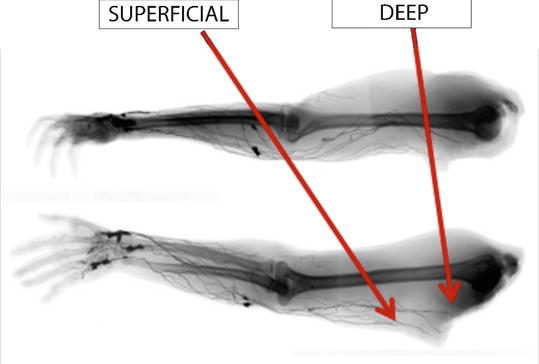

Fig. 29.2

Cadaver lymphangiographic research has increased our knowledge of the anatomy of the lymphatic system. Lymphatics actually travel at multiple levels within the subcutaneous tissues

Mapping techniques can aid in the differentiation between a seroma and a lymphocele, but sometimes the results are inconclusive. Treatment approaches are generally the same for both types of complication. Just as elevated body mass index, extensive subcutaneous dissection, large dead space, and local shearing forces are known factors contributing to seroma formation, this constellation plus division of afferent lymphatics is likely to result in a lymphocele. Additional preventive strategies besides avoiding lymphatic injury have included decreasing dead space with early external compression and internal suturing methods such as quilting sutures. A meta-analysis [5] investigating both compression and quilting sutures in the management of seroma found quilting sutures to be effective, but not so compression. Unfortunately, the infrequency of lymphocele has meant that randomized studies of these maneuvers are neither feasible nor statistically valid. Similarly, another meta-analysis confirmed a minimal benefit of fibrin glue in the management of seroma but lymphocele was not studied. Sclerotherapy employing agents such as doxycycline, alcohol, or bleomycin has been used with varying success in both seroma and lymphocele collections [6, 7].

Obesity, Bariatric Surgery, and Lymphocele Formation

Recent attention has been drawn to an epidemic of overweight problems in the US adult population [8]. Current studies [9] indicate that 68.5 % of American adults are overweight and 34.9 % or 78.6 million [9] are obese; for children, 31.8 % are overweight and 16.9 % are obese. Given the severity of these statistics, the development of procedures that abet weight loss by limiting stomach capacity, such as gastric stapling and banding techniques has been strikingly successful. In 2009, over 200,000 such operations were performed. Because this figure represents only 1 % of the population eligible for weight loss therapy, a significant increase in the number of these procedures performed is anticipated [8]. Following bariatric surgery, massive weight loss is a pleasing result but it can often be accompanied by severely redundant folds of skin located all over the body. The medial thighs, in particular, graphically demonstrate the aesthetic hazards of extreme weight loss often surpassing 150 lbs. This growing population of patients post massive weight loss suffers a variety of body contouring problems secondary to redundant skin. When redundant skin folds of the extremities are treated, it is necessary to excise extensive areas. The wide elevation of flaps of skin in the subcutaneous plane of the inner thighs is particularly prone to injure the numerous lymphatic structures traversing the medial thigh which can occupy different levels within the subcutaneous space and are easily injured. More recent cadaveric studies [10] utilizing a radiopaque lead oxide mixture have clearly illustrated the vulnerability of these channels.

Lymphocele Following Medial Thigh Lift

Just as groin wound complications following arterial revascularization—estimated to have an incidence of 1.8–5 % [11]—can create serious consequences for the patient in the context of infection or even loss of limb, accumulations of lymph (lymphocele) or prolonged lymph drainage (lymphorrea) following medial thigh lift (Figs. 29.3 and 29.4) can also cause prolonged wound morbidity [12]. From wound drainage to cyst or lymphocele formation, these conditions are difficult to diagnose and eradicate. Although an incidence of 3–49 % has been observed after groin and pelvic lymphadenectomies, the exact incidence of lymphocele after medial thigh lift is not well established, but thought to be low, below 10 %. The dissection in the subcutaneous plane that is routinely done during the elevation of medial skin flaps has the potential to injure afferent lymphatics traveling subcutaneously toward the inguinal nodal basin.

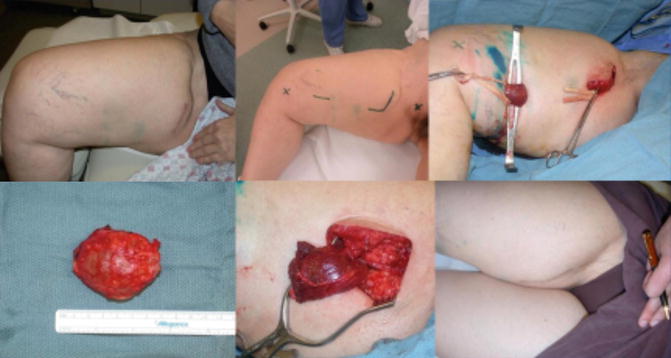

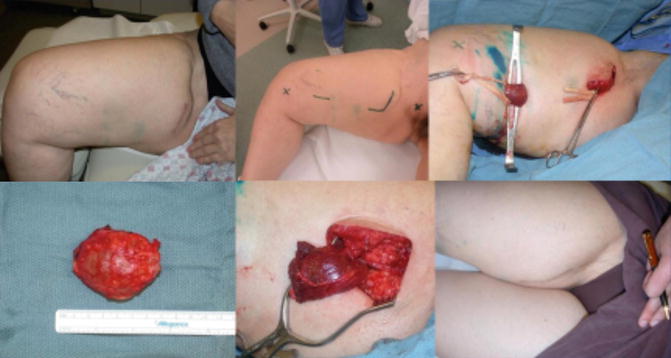

Fig. 29.3

Recurrent lymphocele after thigh lift. Lymphocele is known to occur following injury to the lymphatics traversing the thigh during a medial thigh lift procedure. Such lesions occur when there is a chronic accumulation of lymph, which develops into a pseudocyst-like structure known as a lymphocele. If bandaging and aspiration fail, excision is recommended. The lymphocele structure is depicted in the bottom figure

Fig. 29.4

Treatment of recurrent lymphocele after thigh lift. Operative steps involved in excision of a recurrent lymphocele and reconstruction with a muscle flap of gracilis muscle. After demarcation of the lesion (upper left and center) the lesion is dissected from its surroundings (upper right). The lymphocele mass is shown in the lower left photo. A gracilis muscle flap has been elevated (lower-center). In the lower right photo, patient’s thigh is healed and there has been no recurrence. With permission from [12]

Lymphocele development following a medial thigh lift, and also after brachioplasty (Fig. 29.5), is usually clinically manifest at about 2 weeks postoperative, when it appears as a subtle asymmetry or more obvious bulge. Most patients with a refractory lymphocele relate a history of multiple percutaneous aspirations followed by reaccumulation. Cellulitis often complicates an area that has undergone many such attempts, requiring intravenous antibiotics. Once resolved, the usual approach is to attempt a complete excision and intraoperative ligation of leaking lymphatic channels that are identifiable during the procedure. The success of such an undertaking is known within a few weeks to months, either when complete resolution and contraction of the original site is evident or when a new swelling becomes apparent.

Fig. 29.5

Brachioplasty. Small lymphoceles from superficial injury. Multiple small lymphoceles occurring after brachioplasty. These lesions can be opened and drained repeatedly because of their size. They are more amenable to incision and drainage than thigh lymphoceles and a muscle flap is usually not needed

An additional recurrence in this sequence of events calls for preoperative evaluation with a lymphoscintigram and MRI examination. Our preferred operative technique has included injection of isosulfan blue into the area of the knee of the involved leg, waiting for filling of adjacent dermal lymphatics. Incisions can then be planned to include the borders of the lesion, but also to provide access to sites of lymphatic leakage. Surgical site planning should include access to sites of lymphatic leakage. Surgical site planning should include access to adjacent muscles when a muscle flap is anticipated for filling and closure of the excised lymphocele’s cavity. It is important to both insure completeness of the excision and elimination of lymphatic drainage sites, which should be ligated with absorbable suture. After careful inspection for any evidence of leakage, fibrin glue can be applied to seal any area suspected or demonstrated to contain leaking lymphatics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree