Structure of Skin Lesions and Fundamentals of Clinical Diagnosis: Introduction

“You see, but you do not observe”

—Holmes to Watson in “Scandal in Bohemia,” by Arthur Conan Doyle, 1892

|

The Art and Science of Dermatologic Diagnosis

The diagnosis and treatment of diseases that affect the skin rest on the physician’s ability to use the language of dermatology, to recognize the primary and sequential lesions of the skin, and to recognize the various patterns in which they occur. In this chapter, we discuss a fundamental approach to the patient presenting with a skin problem. We introduce the technical vocabulary of dermatologic description, the “dermatology lexicon.” It is important to know and use this standard terminology, as it is the first step in generating a differential diagnosis. Once a lesion has been described as a pearly, flesh-colored, telangiectatic, ulcerated nodule, the experienced physician puts basal cell carcinoma at the top of the differential diagnosis. It is also important to use standard dermatologic terminology for consistency in clinical documentation, in research, and in communication with other physicians.

The process of examining and describing skin lesions may be likened to that of viewing a painting. First, one stands back and takes in the whole “canvas,” viewing the patient from a few feet away, at which distance an overall assessment of the patient’s general and cutaneous health may be made. One may note such findings as skin color and turgor, presence of pallor or jaundice, degree of sun damage, and the overall number and location of lesions. Next, one looks more closely at the “trees” or “mountains” that make up the landscape, describing and categorizing the specific lesions on the patient. Finally, one may closely examine the details of the canvas, taking in the texture and brush-strokes, using magnification to see the borders of a nevus or compressing a lesion to see if it blanches. Just as a knowledgeable viewer of art may recognize a work of Georges Seurat by its tiny, dot-like brush strokes, an experienced observer of the skin can recognize a melanoma by its asymmetry, irregular borders, and multiple colors.

Approach to the Patient

Dermatology is a visual specialty and some skin lesions may be diagnosed at a glance. Nonetheless, the history is important and in complex cases, such as the patient with rash and fever or the patient with generalized pruritus, history may be crucial. Dermatologists vary in whether they prefer to take a history prior to, during, or after performing a physical examination. In practice, many take a brief history, perform a physical examination, then undertake more detailed questioning based on the differential diagnosis that the examination suggests.

For the following reasons, it is often useful to at least briefly examine the patient before taking a lengthy history:

- Certain skin conditions, such as classic plaque-type psoriasis or molluscum contagiosum, for example, present with such distinctive morphologies that the diagnosis may be immediately obvious, rendering extensive history taking unnecessary.

- A patient’s history may contain “red herrings,” which lead the physician away from, rather than toward, the correct diagnosis. Examination of the patient before taking a history may yield a more complete and unbiased differential diagnosis.

- In certain situations, such as the evaluation of alopecia, initial examination of the patient to determine what type of hair loss is present allows the physician to pursue a line of questions pertinent to that type of alopecia.

In taking a history from a patient presenting with a new skin complaint, the physician’s primary goal is to establish a diagnosis, with a secondary goal of evaluating the patient as a candidate for therapy. In patients whose diagnosis is already established, the physician’s goals are to reevaluate the original diagnosis, monitor disease progress and complications, and modify treatment accordingly.

Box 5-1 presents a suggested approach to obtaining the history in a patient presenting with a skin problem. Clearly, not all of the questions are necessary for every patient. The physician will need to tailor the history depending on whether the chief complaint is a growth or an eruption, a nail or hair disorder, or another condition, and whether it is a new problem or a follow-up visit for an ongoing condition.

CHIEF COMPLAINT AND HISTORY OF THE PRESENT ILLNESS

|

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY

|

The complete cutaneous examination includes inspection of the entire skin surface, including often-overlooked areas such as the scalp, eyelids, ears, genitals, buttocks, perineal area, and interdigital spaces; the hair; the nails; and the mucus membranes of the mouth, eyes, anus, and genitals. In routine clinical practice, not all of these areas are examined unless there is a specific reason to do so, such as a history of melanoma or a particular localizing complaint. A guide to performing the physical examination of the patient presenting with a skin problem is presented in Box 5-2.

GENERAL IMPRESSION OF THE PATIENT

|

Describe the Distribution of Lesions: Localized (isolated), grouped, regional, generalized, universal, symmetrical, sun-exposed, flexural, extensor extremities, acral, intertriginous, dermatomal, follicular |

PRIMARY LESIONS

|

PALPATION

|

ASPECTS OF GENERAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION THAT MAY BE HELPFUL

|

Although it is not always essential or practical to perform a complete skin examination, there are many advantages to doing so, especially for new patients and challenging cases:

- Identification of potentially harmful lesions (e.g., skin cancers) of which the patient is unaware; any patient with a history of skin cancer or a chief complaint of a “new growth” deserves a full skin examination.

- Identification of benign lesions (e.g., seborrheic keratoses, angiokeratomas) that the patient was concerned about but reluctant to mention, thereby enabling the physician to provide reassurance.

- Finding hidden clues to diagnosis (e.g., scabies lesions on the penis, psoriatic plaques on the buttocks, Wickham striae of lichen planus on the buccal mucosa, nail pitting in alopecia areata).

- Opportunity for patient education (e.g., lentigines are a sign of sun damage and suggest the need for improved sun protection).

- Opportunity to convey the physician’s concern about the patient’s skin health as a whole. Patients appreciate this and also regard the physician as thorough.

Despite the advantages of performing a full cutaneous examination, numerous barriers exist that may prevent the dermatologist from performing such an evaluation for every patient. Understandably, patients may decline a full examination when their chief complaint is relatively minor or localized, such as a wart or acne. In other cases, patients may express resistance to disrobing for a full examination due to embarrassment, especially when the physician is of the opposite gender. Sometimes the physician is uncomfortable performing a complete skin examination with the concern that a patient may misinterpret the examination as improper. In many instances, time constraints and lack of personnel to serve as chaperones limit the ability to perform full skin examination.

A complete skin examination is most effective when performed under ideal conditions. It is most important to have excellent lighting, preferably bright, even light that simulates the solar spectrum. Without good lighting, subtle but important details may be missed. The patient should be fully undressed, wearing only a gown that is easily moved aside, with a sheet over the legs, if desired. Underwear, socks, and shoes should be removed, as should any makeup or eyeglasses. The examining table should be at a comfortable height, with a head that reclines, an extendable footrest, and gynecologic stirrups. The examining room should be at a comfortable temperature for the lightly dressed patient. It should contain a sink for hand washing and disinfecting hand foam, as patients are reassured by seeing their physician wash hands before the examination. If the patient and physician are of opposite genders, having a chaperone in the room can make the examination more comfortable for both.

Although the physician’s eyes and hands are the only essential tools for examination of the skin, the following are often useful and highly recommended:

- A magnifying tool such as a loupe, magnifying glass, and/or dermatoscope.

- A bright focused light such as a flashlight or penlight to sidelight lesions.

- Glass slides or a hand magnifier for diascopy.

- Alcohol pads to remove scale or surface oil.

- Gauze pads or tissues with water for removing makeup.

- Gloves to be used for examination when scabies or another highly infectious condition (secondary syphilis) is suspected, when examining mucus membranes, and vulvar and genital areas, and when performing any procedure.

- A ruler for measuring lesions.

- Number 15 and number 11 scalpel blades for scraping and incising lesions, respectively.

- A camera for photographic documentation.

- A Wood’s lamp (365 nm) for highlighting subtle pigmentary changes.

Just as there is no one correct way to perform a general physical examination, each physician approaches the complete skin examination with his or her own style. A common thread to effective styles of skin examination is consistency in the order of examining different body areas to ensure that no areas are overlooked. One approach to the complete skin examination is presented here. First, observe the patient at a distance for general impressions (e.g., asymmetry due to a stroke, obesity, pallor, fatigue, jaundice). Next, examine the patient in a systematic way, usually from head to toe, uncovering one area at a time to preserve patient modesty. Move the patient (e.g., from sitting to lying) and the illumination as needed for the best view of each body area. Palpate growths to determine whether they are soft, fleshy, firm, tender, or fluid-filled. Use of the hands to stretch the skin is especially useful in diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, in which stretching skin reveals a “pearly” quality often not seen on routine inspection. A magnifier worn on the head leaves both hands free for palpation of lesions. Certain lesions, such as porokeratosis, are best examined with side lighting that reveals depth and the details of borders. During the examination, patients often find it reassuring for the physician to name and demystify benign lesions as they are encountered.

Special examination techniques for hair disorders are discussed in Chapter 88; these include having the patient sit in a chair so that the entire scalp is easily examined, parting the patient’s hair at the front and occiput, and gently tugging on hairs to determine the fraction of loose (telogen) hairs. Examination of the nails is discussed in Chapter 89.

After completing the examination, it is important to document the skin findings, including the type of lesions and their locations, either descriptively or on a body map. Careful documentation is particularly important for suspicious lesions that are to be biopsied, so that the exact location may be found and definitively treated at a later date. Instant or digital photography is a useful adjunct for documentation.

Introduction to Morphology

Siemens (1891–1969) wrote, “he who studies skin diseases and fails to study the lesion first will never learn dermatology.” His statement reinforces the notion that the primary skin lesion, or the evolution thereof, is the essential element on which clinical diagnosis rests. Joseph Jakob von Plenck’s (1738–1807) and Robert Willan’s (1757–1812) work in defining basic morphologic terminology have laid the foundation for the description and comparison of fundamental lesions, thereby facilitating characterization and recognition of skin disease as, Wolff and Johnson state, to read words, one must recognize letters; to read the skin, one must recognize the basic lesions. To understand a paragraph, one must know how words are put together; to arrive at a differential diagnosis, one must know what the basic lesions represent, how they evolve, and how they are arranged and distributed.

Variation and ambiguity in the morphologic terms generally accepted by the international dermatology community have engendered barriers to communication among physicians of all disciplines, including dermatologists. In dermatologic textbooks, the papule, for example, has been described as no greater than 1 cm in size, less than 0.5 cm, or ranging from the size of a pinhead to that of a split pea. Thus, in forming a mental image of a lesion or eruption after hearing its morphologic description, physicians sometimes remain irresolute. The mission of the Dermatology Lexicon Project has been to create a universally accepted and comprehensive glossary of descriptive terms to support research, medical informatics, and patient care. Morphologic definitions in this chapter parallel and amplify those of the Dermatology Lexicon Project. Table 5-1 contains a summary of the lesions discussed.

Raised | Depressed | Flat | Surface Change | Fluid Filled | Vascular |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Papule Plaque Nodule Cyst Wheal Scar Comedo Horn Calcinosis | Erosion Ulcer Atrophy Poikiloderma Sinus Striae Burrow Sclerosis | Macule Patch Erythema Erythroderma | Scale Crust Excoriation Fissure Lichenification Keratoderma Eschar | Vesicle Bulla Pustule Furuncle Abscess | Purpura Telangiectasia Infarct |

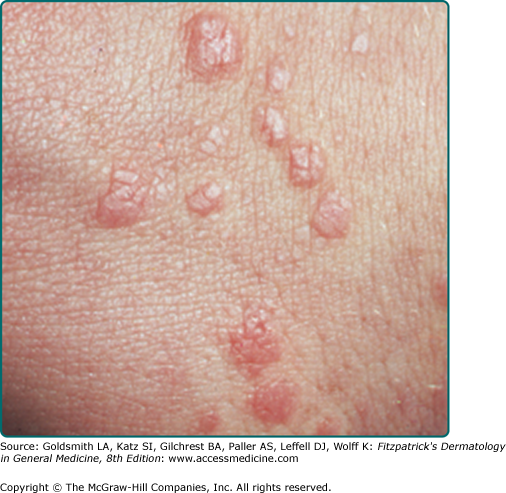

A papule is a solid, elevated lesion less than 0.5 cm in size in which a significant portion projects above the plane of the surrounding skin. Papules surmounted with scale are referred to as papulosquamous lesions. Sessile, pedunculated, dome-shaped, flat-topped, rough, smooth, filiform, mammillated, acuminate, and umbilicated constitute some common shapes and surfaces of papules. A clinical example is lichen planus (Fig. 5-1; see Chapter 26).

A plaque is a solid plateau-like elevation that occupies a relatively large surface area in comparison with its height above the normal skin level and has a diameter larger than 0.5 cm. Plaques are further characterized by their size, shape, color, and surface change. A clinical example is psoriasis (Fig. 5-2; see Chapter 18).

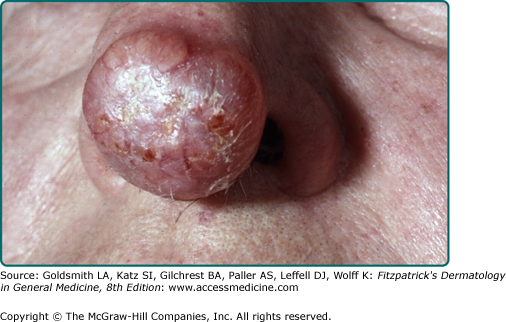

A nodule is a solid, round or ellipsoidal, palpable lesion that has a diameter larger than 0.5 cm. However, size is not the major consideration in the definition of nodule. Depth of involvement and/or substantive palpability, rather than diameter, differentiates a nodule from a large papule or plaque. Depending on the anatomic component(s) primarily involved, nodules are of five main types: (1) epidermal, (2) epidermal–dermal, (3) dermal, (4) dermal–subdermal, and (5) subcutaneous. Some additional features of a nodule that may help reveal a diagnosis include whether it is warm, hard, soft, fluctuant, movable, fixed, or painful. Similarly, different surfaces of nodules, such as smooth, keratotic, ulcerated, or fungating, also help direct diagnostic considerations. A clinical example of a nodule is nodular basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 5-3; see Chapter 115).

Tumor, also sometimes included under the heading of nodule, is a general term for any mass, benign or malignant. A gumma is, specifically, the granulomatous nodular lesion of tertiary syphilis.

A cyst is an encapsulated cavity or sac lined with a true epithelium that contains fluid or semisolid material (cells and cell products such as keratin). Its spherical or oval shape results from the tendency of the contents to spread equally in all directions. Depending on the nature of the contents, cysts may be hard, doughy, or fluctuant. A clinical example is a cystic hidradenoma (Fig. 5-4; see Chapter 119).

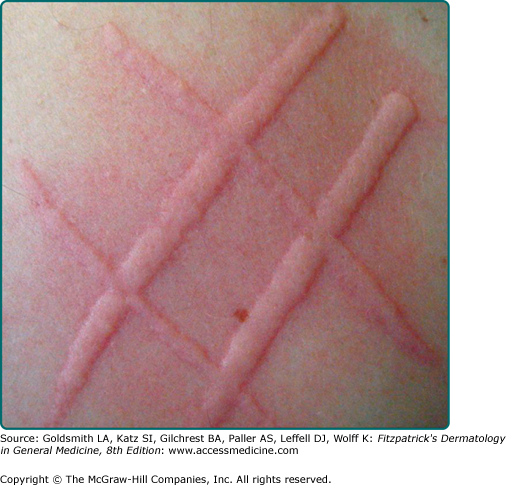

A wheal is a swelling of the skin that is characteristically evanescent, disappearing within hours. These lesions, also known as hives or urticaria, are the result of edema produced by the escape of plasma through vessel walls in the upper portion of the dermis. Wheals may be tiny papules or giant plaques, and they may take the form of various shapes (round, oval, serpiginous, or annular), often in the same patient. Borders of a wheal, although sharp, are not stable and in fact move from involved to adjacent uninvolved areas over a period of hours. The flare, or ring of pink erythema, of a wheal may be intense if superficial vessels are dilated. If the amount of edema is sufficient to compress superficial vessels, wheals may in fact be white in the center or around the periphery, producing a zone of pallor. With associated inflammatory disruption of the vessels walls, wheals may have a deeper red color, may be purpuric, and are more persistent. A clinical example is dermatographism (Fig. 5-5; see Chapter 38).

Angioedema is a deeper, edematous reaction that occurs in areas with very loose dermis and subcutaneous tissue such as the lip, eyelid, or scrotum. It may occur on the hands and feet as well, and result in grotesque deformity.

A scar arises from proliferation of fibrous tissue that replaces previously normal collagen after a wound or ulceration breaches the reticular dermis. Scars have a deeper pink to red color early on before becoming hypo- or hyperpigmented. In most scars, the epidermis is thinned and imparts a wrinkled appearance at the surface. Adnexal structures, such as hair follicles, normally present in the dermis are absent. Hypertrophic scars typically take the form of firm papules, plaques, or nodules. Keloid scars are also elevated. Unlike hypertrophic scars (see eFig. 5-5.1; see Chapter 66), keloids exceed, with web-like extensions, the area of initial wounding. Atrophic scars are thin depressed plaques.

A comedo is a hair follicle infundibulum that is dilated and plugged by keratin and lipids. When the pilosebaceous unit is open to the surface of the skin with a visible keratinaceous plug, the lesion is referred to as an open comedo. The black color of the comedo is due to the oxidized sebaceous content of the infundibulum (“blackhead”). A closed infundibulum in which the follicular opening is unapparent accumulates whitish keratin and is called a closed comedo. A clinical example is comedonal acne (Fig. 5-6; see Chapter 80).

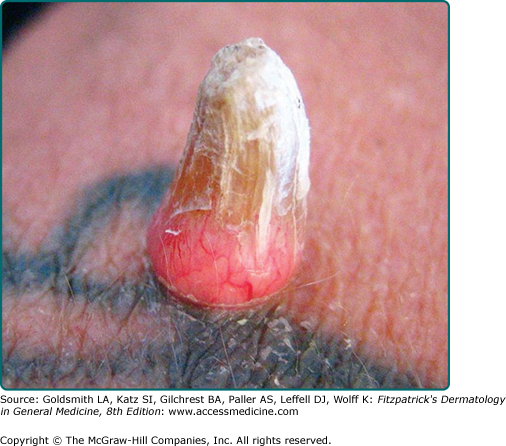

A horn is a hyperkeratotic conical mass of cornified cells arising over an abnormally differentiating epidermis. A clinical example is verruca vulgaris (see eFig. 5-6.1; see Chapter 196).

Deposits of calcium in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue may be appreciated as hard, whitish nodules or plaques, with or without visible alteration of the skin’s surface. A clinical example is cutaneous calcinosis in dermatomyositis (see eFig. 5-6.2; see Chapter 156).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree