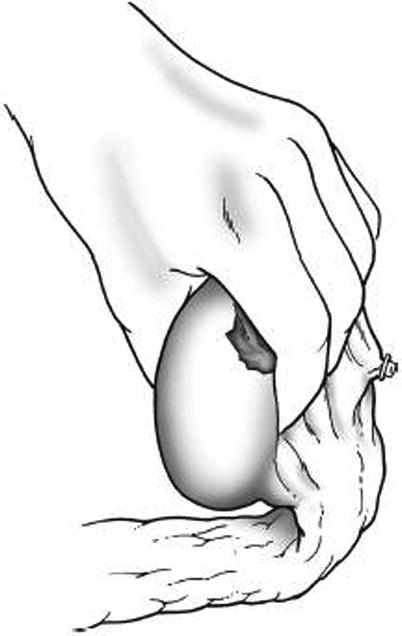

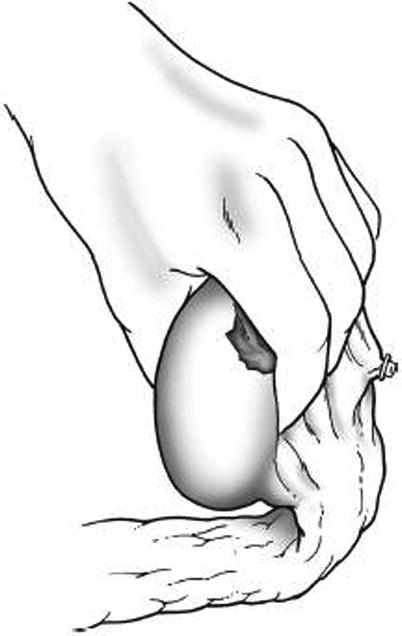

Grade

Description

Figure

I

Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth

1a

II

Capsular tear, 1–3 cm parenchymal depth that does not involve a trabecular vessel

1b

III

>3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels

1c

IV

Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels causing major devascularization (>25 % of spleen)

1d

V

Completely shattered spleen or hilar vascular injury with devascularized spleen

1e

Fig. 54.1

An illustrated guide to the 1994 modification of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Splenic Injury Grading Scale [7]

54.1 Exposure

As with most cases of traumatic hemorrhage, a generous midline incision is the best approach for splenic trauma. If further exposure of the left upper quadrant is needed, as in the case of obese patients or those with an unusually narrow costal angle, you can extend the incision in the left hypochondrium – although it is rarely needed.

After opening the abdomen, you should pack all four quadrants or suction to clear hemoperitoneum and rapidly identify obvious injuries. A series of 225 penetrating splenic injuries found concomitant diaphragmatic (60 %), hollow viscus (38 %), liver (32 %), renal (25 %), abdominal vascular (10 %), and pancreatic (1 %) injuries. If you identify more pressing injuries to address than that of the spleen, you should quickly address them. In most cases of multiple injuries, with the exception of abdominal vascular injuries, you should address the spleen first, as continued bleeding from the organ can harm the patient due to both ongoing blood loss and obscuring the operative field. If you are having difficulty identifying the source of bleeding in a particularly bloody abdomen despite packing and suctioning, you will identify the main source of bleeding by turning to the site of clot formation. Defibrinated blood tends to spread freely throughout the peritoneal cavity whether or not the spleen is the source.

After quelling the bleeding with suctioning or packing the four quadrants and rapidly examining for associated injury, pack the small bowel inferiorly into the lower abdomen and pelvis. Then, deliver the spleen into the operative field with gentle inferior and medial traction so as to not exacerbate the underlying injury. Depending on the length and density of the splenic attachments to surrounding structures, you may not be able to fully deliver the organ without mobilization.

54.2 Mobilization

Start mobilizing the spleen by sharply dividing its superolateral attachment, the splenophrenic ligament, to the level of the esophageal hiatus, followed by its inferolateral attachment, the splenorenal ligament. Take care during this maneuver not to injure the left adrenal gland which is characteristically located in an anti-hilar position. Division of these attachments may be facilitated by placing a clamp or finger under these attachments prior to division to develop a plane (see Fig. 54.2).

Fig. 54.2

Splenic ligaments and attachments. Division of these attachments may be facilitated by placing a clamp or finger under these attachments prior to division to develop a plane

Once the lateral and inferior attachments are divided (Fig. 54.3), you rotate the spleen medially by cupping the palm of the right hand around the anti-hilar side of the spleen and engaging the fingers of your non-dominant hand around the posterior aspect of the organ in the plane between itself and the retroperitoneal lining of the kidney. It will then be possible to bluntly dissect behind the tail of the pancreas and deliver the spleen and pancreatic tail as a unit into the midline wound. The degree of dissection required behind the tail will be determined by the length of the patient’s pancreas with shorter organs requiring less mobilization (see Fig. 54.4).

Fig. 54.3

Gently pull the spleen to easily detach the ligaments

Fig. 54.4

Mobilize the spleen and pancreatic tail gently after it has been freed of all attachments

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree