Chapter 35 Special considerations of age

The pediatric burned patient

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

The incidence of burn injuries has declined steadily over the past two decades. Approximately 1.25 million people are burned in the United States every year, of which one-third are children;1 60 000–80 000 patients sustain severe enough burns to require hospital admission;2 30 000 children require hospital admission for treatment of their burn injuries.1 About 4000 burn patients die each year,2 and approximately 1000 of them are children.3

Improvements have been made in the reduction of morbidity and mortality related to burns over the past few decades. Advances in fluid resuscitation, early surgical excision and grafting of the burn wound, infection control, treatment of inhalation injury, nutritional support, and support of hypermetabolic response to burns have contributed to a 50% decline in burn-related deaths and hospital admissions in the United States.2 This overall improvement in mortality is most perceptible in children. In 1949, Bull and Fisher reported the expected 50% mortality rate for 49% total body surface area (TBSA) burn in children aged 0–14.4 This has improved to 50% expected mortality in 98% TBSA burn in the same population group.5

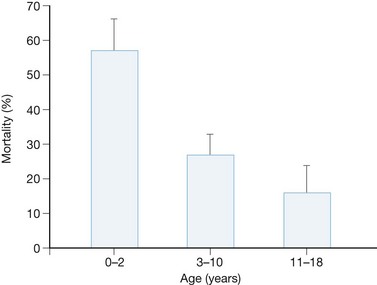

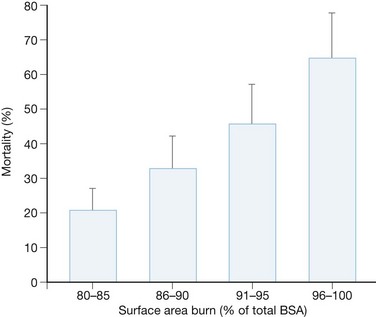

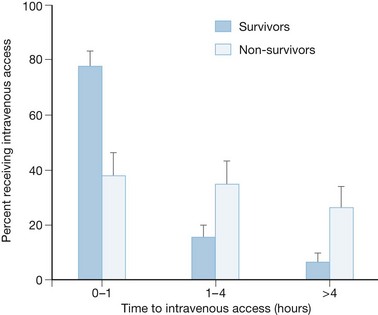

In a review of 103 children with >80% TBSA burns over a 15-year period, it was found that 69 patients survived, with an overall mortality of 33%. Mortality was greatest in children under 2 years of age and in burns >95% TBSA (Figs 35.1 and 35.2).6 Another major predictor of mortality was the length of delay to intravenous (IV) access (Fig. 35.3). Patients that received resuscitation fluids within the first hour had a significantly higher chance of survival.6 The mortality rate also increased significantly with inhalation injury, sepsis and multiorgan failure. In no pediatric patient, no matter how large the burn, how young, or with what type of inhalation injury, could it be accurately predicted at the time of admission whether they would live or die.6

Resuscitation

There is a systemic capillary leak after a large burn, which increases with burn size. Capillary usually regains competence 18–24 hours after burn injury. IV access should be established immediately for the administration of resuscitative fluid. Increased delays to commencement of resuscitation of burned patients result in worse outcomes and should be avoided.6 Therefore it is crucial that IV access be obtained as early as possible, even though such access may be difficult to obtain. Owing to the small circulating volume in children, delays in resuscitation for periods as short as 30 minutes can result in profound shock. Peripheral IV access is preferred, and it may go through burned skin if necessary. IV access should be well secured. When peripheral IV is not available because of severe extremity burns, a central venous line may be placed. Children with large burns should have two large-bore IV lines for fluid administration. The presence of two IV lines also provides a safety margin if one infiltrates, to allow continued resuscitation while another line is re-established. Either internal jugular, subclavian or femoral lines can be obtained, but femoral venous access may be easier to obtain in edematous patients.

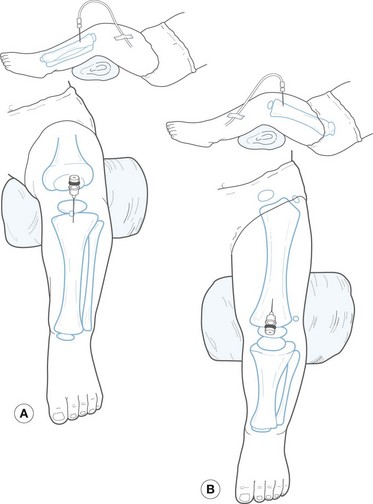

When vascular access is unobtainable the intraosseous route is a viable option. Fluid volumes in excess of 100 mL/h can be administered directly into the bone marrow.7 Intramedullary access can be utilized in the proximal tibia until IV access is accomplished. A 16–18 gauge bone marrow aspiration needle, spinal needle, or commercially available intraosseous needle can be used to cannulate the bone marrow compartment. Although previously advocated only for children younger than 3 years of age, intraosseous fluid administration can be safely performed in all pediatric age groups.8 The anterior tibial plateau, medial malleolus, anterior iliac crest, and distal femur are preferred sites for intraosseous infusion. The needle should be introduced into the bone, avoiding the epiphysis, either perpendicular to the bone or at a 60° angle, with the bevel facing the greater length of bone (Fig. 35.4). The needle has been properly inserted when bone marrow can be freely aspirated. The needle should be well secured to prevent inadvertent removal. Fluid should be allowed to infuse by gravity drip. The use of pumps should be discouraged in case the needle is dislodged from the marrow compartment.

Figure 35.4 Intraosseous line placement in the proximal tibia (a) and distal femur (b).

(Redrawn with permission from Fleisher G, Ludwig S, eds. Textbook of pediatric emergency medicine, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1988: 268.)

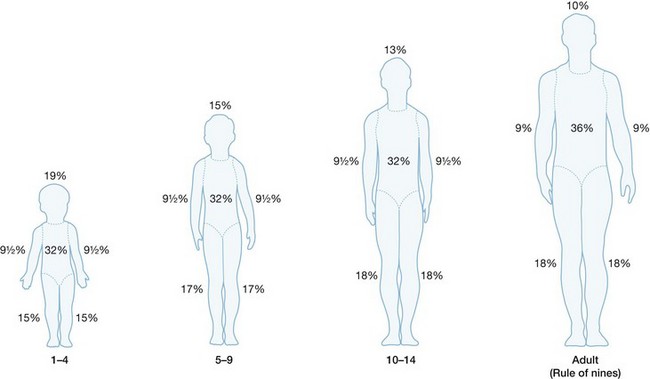

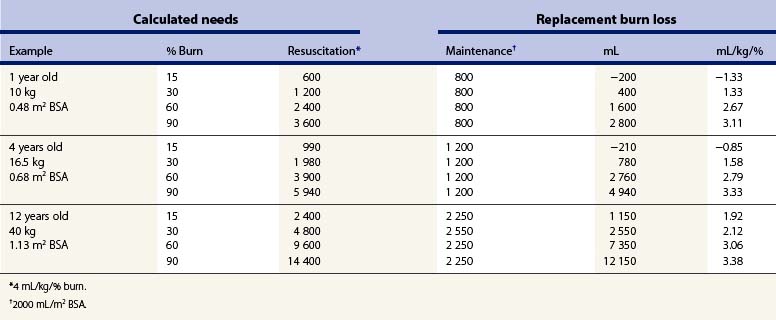

Fluid losses are proportionally greater in children owing to their small body weight to body surface area ratio. Normal blood volume in children is approximately 80 mL/kg body weight and in neonates 85–90 mL/kg, compared to an adult whose normal blood volume is 70 mL/kg. Evaporative water losses in a 20% TBSA burn in a 10 kg child are 475 mL or 59% of the circulating volume, whereas the same size burn in a 70 kg adult causes the loss of 1100 mL or only 22% of blood volume. The commonly used ‘rule of nines’, useful in adults and adequate in adolescents, does not accurately reflect the burned body surface area of children under 15 years of age (Fig. 35.5). The standard relationships between body surface area and weight in adults do not hold true in children, as infants possess a larger cranial surface area and a smaller area in the extremities than adults. Most routinely used resuscitation formulas were developed using adult patients and are almost exclusively weight-based. Since the linear relationship between weight and body surface area does not exist in children, use of these formulas in children results in under- or over-resuscitation (Table 35.1).

Figure 35.5 The ‘rule of nines’ altered for the anthropomorphic differences of infancy and childhood.

Table 35.1 Resuscitation by the Parkland formula only compared to maintenance fluid requirements alone

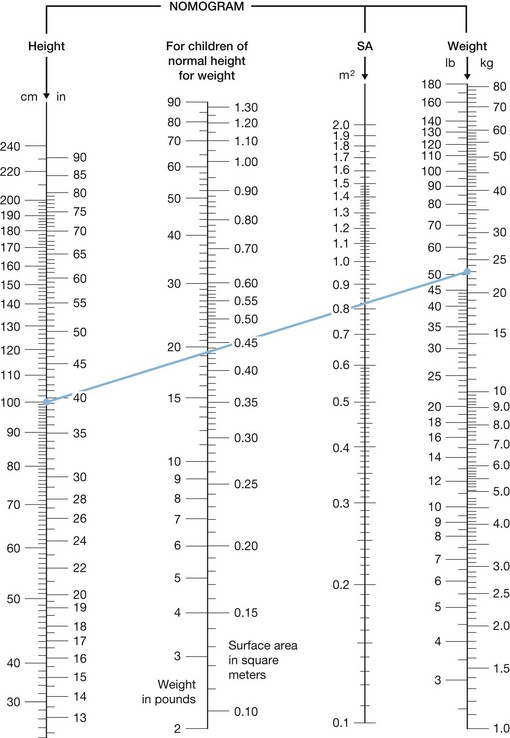

Pediatric burn patients should therefore be resuscitated using formulas based on body surface area, which can be calculated from height and weight using a standard nomogram (Fig. 35.6) or formulas (Table 35.2). The most commonly used resuscitation formula in pediatric patients calls for the administration of 5000 mL/m2 TBSA burned plus 2000 mL/m2 TBSA for maintenance fluid given over the first 24 hours after burn, with half the volume administered during the initial 8 hours and the second half given over the following 16 hours.9 The subsequent 24 hours, and for the rest of the time their burn wound is open, require 3750 mL/m2 TBSA burned or remaining open area plus 1500 mL/m2 TBSA for maintenance requirements. The fluid requirement decreases as a patient achieves more wound coverage and healing. As in the adult patient, resuscitation formulas offer a guide for the amount of fluid necessary for replacing lost volume in children, and the amount of fluid should be titrated according to the patient’s response.

Table 35.2 Formulas for calculating body surface area (bsa)

| Dubois formula | BSA (m2) = ht (cm)0.725 × wt (kg)0.425 × 0.007184 |

| Jacobson formula | BSA (m2) = [ht (cm) + wt (kg) − 60]/100 |

Hyponatremia is a frequently observed complication in pediatric patients after the first 48 hours post burn. Frequent monitoring of serum sodium is necessary to guide appropriate electrolyte and fluid management. Children of under 1 year of age may require more sodium supplementation because of higher urinary sodium losses. Potassium losses are usually replaced with oral potassium phosphate rather than potassium chloride, as hypophosphatemia is frequent in this population.10 Calcium and magnesium losses also must be supplemented.

Assessment of resuscitation

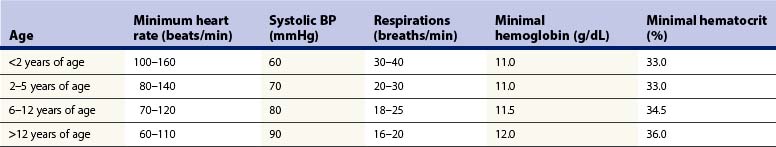

Children frequently develop a reflex tachycardia after even the most trivial injury due to an overexuberant catecholamine response to the trauma or anxiety. Systolic blood pressures <100 mmHg are common in children younger than 5 years of age (Table 35.3). Young children with immature kidneys have less tubular concentrating ability than adults, and urine production may continue in spite of hypovolemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree