(1)

Department of Dermatology, Freiburg University Medical Center, Freiburg, Germany

Abstract

Six well established archetypical patterns of cutaneous mosaicismcan be distinguished. The best known pattern is the system of Blaschko’s lines. Analogous linear or sectorial patterns of mosaicism have been documented in other human organs such as the bones, the teeth, the lens, and the retina. Moreover, the hereditary trait brindle as noted in dogs, cattle, horses and other mammals represents a perfect counterpart of the human lines of Blaschko. – The checkerboard pattern is characterized by flag-like or block-like patches. In the phylloid pattern, the leaf-like or oblong macules are reminiscent of the floral ornaments of Jugendstil or art nouveau. Large round patches without midline separation are the archetypical pattern of giant melanocytic nevi. A peculiar pattern of lateralization is noted in the X-linked dominant, male-lethal trait, CHILD syndrome. The sash-like pattern, as documented in children with cutis tricolor of the Ruggieri-Happle type, is characterized by large oblique hyper- or hypopigmented macules reminiscent of a sash, and by large round or flag-like areas of hyper- or hypopigmention. This pattern does not respect the dorsal and ventral midline.

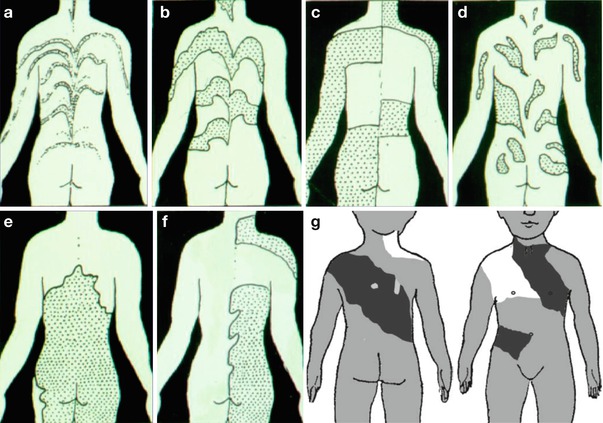

Six archetypical patterns of cutaneous mosaicism can so far be distinguished: (1) lines of Blaschko, (2) checkerboard pattern, (3) phylloid pattern, (4) patchy pattern without midline separation, (5) lateralization pattern, and (6) the sash-like pattern (Figs. 5.1 and 5.2). These distinct types of archetypical arrangement should not be conflated with the various shapes of the individual smaller mosaic skin lesions that may be round, oval, oblong, or triangular and may or may not have indented borders [69].

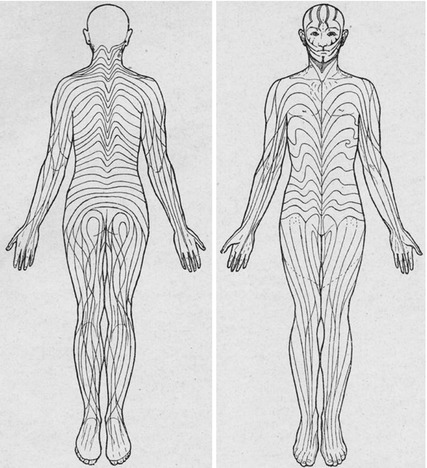

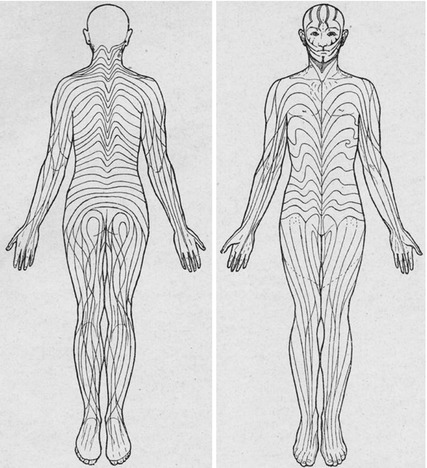

Fig. 5.1

Archetypical patterns of cutaneous mosaicism. (a) Type 1a, lines of Blaschko arranged in narrow bands; (b) type 1b, lines of Blaschko arranged in broad bands; (c) type 2, checkerboard pattern; (d) type 3, phylloid pattern; (e) type 4, large non-slanting patches without midline separation; (f) type 5, lateralization pattern; (g) type 6, sash-like pattern (Ruggieri-Happle type)

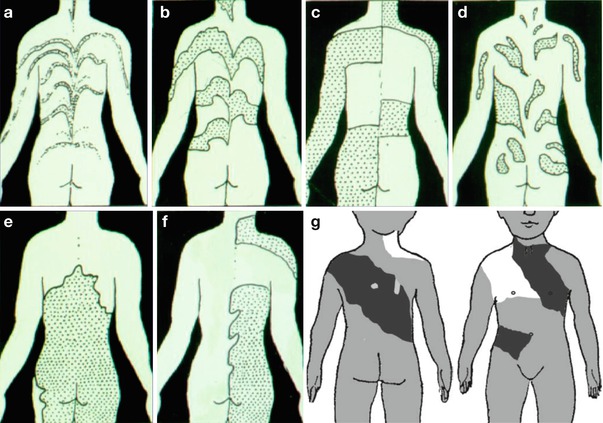

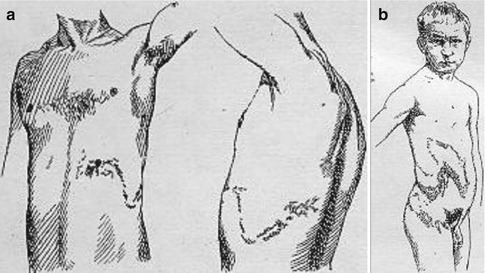

Fig. 5.2

Clinical examples of the archetypical patterns as shown in Fig. 5.1. (a) Blaschko-linear hypermelanosis in narrow bands; (b) McCune-Albright syndrome (Courtesy of Dr. Jean-Paul Ortonne, Nice, France); (c) systematized Becker nevus (Courtesy of Dr. Aïcha Salhi, Algiers, Algeria); (d) phylloid hypermelanosis [37] (Reprinted with permission from John Wiley & Sons, USA); (e) giant melanocytic nevus; (f) CHILD syndrome; (g) cutis tricolor of the Ruggieri-Happle type [60]

5.1 Lines of Blaschko

In 1901 Alfred Blaschko (Fig. 5.3) published his atlas on linear skin diseases, containing the well-known diagram of what he called the “nevus lines” [6]. From more than 170 case reports sent to him from colleagues of many European countries, he depicted an archetypical pattern of lines by applying woollen threads to a plaster of Paris classical statue that he had bought in Berlin from an Italian street vendor. He wrote: “I have tried … to delineate, from the total collection of available cases, a system of lines on the surface of the body representing the typical pattern that the linear nevi follow.” These lines form a characteristic V figure reminiscent of a fountain on the back (Fig. 5.4) and an S figure on the lateral aspects of the trunk (Fig. 5.5). Sometimes they produce whorls on the trunk or limbs (Fig. 5.6). On the arms and legs, they run in a less distinctive, perpendicular pattern. Blaschko clearly stated that this system of lines was in no way related to the zones of radicular innervation. “The linear nevi are a sequela of developmental disturbances for which it is not necessary to assume a preceding disorder of the nervous system.” He assumed that “during the initial stage of embryogenesis, rather intense movements and shifts of the individual cutaneous territories occur along these lines.”

Fig. 5.3

Alfred Blaschko (Courtesy of the late Dr. Hermann Blaschko, Oxford, UK)

Fig. 5.4

Blaschko’s original drawing of his “nevus lines” [6]. The head was mapped in a rather cursory way and left in part completely free because of lack of information

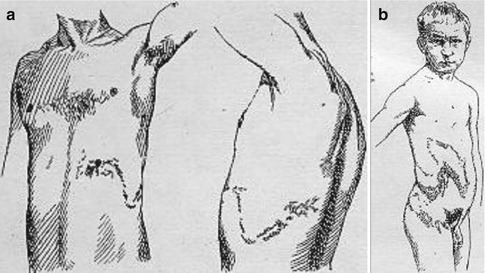

Fig. 5.5

Blaschko’s lines forming characteristic S figures on the lateral aspect of the trunk (From Blaschko’s atlas. (a) Plate XII, Fig. 4 “Nerve nevus. University Hospital Breslau”. (b) Plate XII, Fig. 2 “Naevus verrucosus linearis, from Alexander-Blaschko” [see 1,5] [6])

Fig. 5.6

Systematized epidermal nevus (“ichthyosis hystrix Hebrae after Gassmann”) producing multiple whorls on the trunk (From Blaschko’s atlas, Plate XV, Fig. 4 [6])

Blaschko had published his essential message already in 1895 [1, 5]: “Why should we resort to a pathological event – that is, in top of that, hypothetical, – in another far distant organ system and take the skin disorder as a secondary phenomenon, if our need of causality is satisfied by the simple and certainly plausible assumption of a growth disturbance within the epidermis itself… Not to mention that the influence of the nervous system on processes of growth is not at all proven as yet and more than doubtful for the sequential stages of embryonic life wherein the nerves will almost certainly play a minor role only… But I believe to be able to postulate with certainty that the epidermis, especially of the trunk, is divided into a series of more or less parallel territories…If we assume that, during the months when differentiation takes place, a disturbing factor would interfere, then it would easily be possible that only particular territories are involved, whereas intervening regions are healthy” [5]. Blaschko didn’t know anything about genes and mutations, but by choosing the words “a disturbing factor” he anticipated the explanatory genetic mechanisms as later brought to light in the second half of the past century.

In 1901, Montgomery [53] presented similar ideas but by no means he did this “at the same time” [62]. On the contrary, he explicitly referred to Blaschko’s thoughts [1, 5] when arguing that linear nevi do apparently not follow the course of nerves or blood vessels, Voigt’s lines, the lines of cleavage of the skin, or the metameres of the body. He favored Blaschko’s idea that “the streaks may be due to the streams or trend of growth of the tissues and to the adaptation of the embryonic sutures…” Accordingly, “a nævus linearis originates at an early stage in the development of the fœtus, when the embryonic layers are still a plastic mass….Imagining the affected cells or groups of cells to lie in the plastic mass like currants in dough, one can see that such a group lying in the region which will afterwards become the back of the neck might be pulled toward the median line when the skin closes over the neural canal, and its individual constituents become scattered along this line as the fœtus elongates… Another group situated over the place where a limb will afterwards bud out, would be stretched along in a line with the budding limb, and the line would tend to follow all the twists and turns of the limb as it grew out, exactly as Kaposi has so graphically described.”

During the first half of the past century, however, Blaschko’s idea was not understood by others and fell into oblivion. This may in part be explained by the fact that his pioneering atlas carried the misleading title “The nerve distribution in the skin in its relationship to the diseases of the skin” [6]. This wording simply reflected an erroneous belief of those professors who had invited Blaschko to speak at the 7th Congress of the German Dermatological Society held in Breslau in May 1901. As a consequence, only those who opened the book had a chance to become aware of the author’s message that there was no relationship between the nervous system and the “nevus lines.”

For example, Haensch [23] reported in 1961 a case of what is today called “blaschkitis” and argued: “Because of the segmental arrangement, a disorder of the corresponding spinal root must have been present as a factor determining the dermatosis… The configuration of the eczema shows in an unusually clear and pure way the topographically determining role of neural factors in the origin of eczema.” And in 1964, the Swiss anatomist Töndury [68] wrote: “Hence we can state that the skin, apart from a short period of segmentation of the corium anlage within the dorsal area of the embryo, is not segmented at any time of its development.” If this statement would be true, the pattern of Blaschko’s lines would remain unexplained. As a remote echo of such erroneous assumptions, we find even today reports of linear nevi said to be arranged in a “zosteriform” or “dermatomal” pattern [2, 14–16, 72].

In 1969 MacDonald and Sims [48], being unaware of Blaschko’s work, studied photographs and descriptions as presented in case reports, as well as 16 cases in their own records and stated that “no association could be found between the lesions and anatomical features of the skin.” They concluded that “the epidermis is not…inherently segmental.”

Remarkably, however, we find Blaschko’s diagram of the “nevus lines” in two Dutch textbooks on skin diseases that appeared during the 1940s [9, 63] and in a German edition of one of these monographs [64].

In 1965, Curth and Warburton [12] discussed the relationship between the Lyon hypothesis and incontinentia pigmenti. They were unaware of Blaschko’s work and stated that “application of the Lyon theory does not explain (1) the usual limitation of the pigment to certain regions, (2) its patterned rather than patchy distribution, and (3) the presence of the same pattern in the few males who manifest the disease.”

During the late 1970s Blaschko’s lines were rediscovered independently in Canada and Germany. In 1976, Jackson [38] wrote that “the embryological explanation of Blaschko’s lines is not at all clear. Other markers in addition to the skin findings are needed to determine the time and the nature of the change responsible for these lines…I have been unable even to make a guess at what stage of development the changes occur which could provide a mechanism by which the localization of Blaschko’s lines is determined. It would be helpful to tie in Blaschko’s lines with some other dateable embryological event…” At the same time, such explanatory mechanisms and dateable events were postulated in the form of X-chromosome inactivation, early postzygotic mutations, and gametic half-chromatid mutations [25, 26, 28]. This concept is illustrated in Fig. 5.7 [30]. When doing this, I was put on the right track by the thoughts of the great geneticist Widukind Lenz who, without mentioning Blaschko’s lines, had already proposed in 1970 to explain the linear lesions of incontinentia pigmenti by the mechanism of X inactivation, and systematized epidermal nevi by somatic mutations [46].

Fig. 5.7

Explanation of the pattern of Blaschko’s lines. At an early developmental stage, an admixture of mutant and normal progenitor cells is arranged along the primitive streak. Their transversal proliferation interferes with the longitudinal growth and flexion of the embryo, giving rise to a fountain-like pattern on the back [30] (Reprinted with permission from S. Karger AG, Basel, Switzerland)

Because of lack of informative cases, Blaschko had left in his diagram the scalp as a “terra incognita” [6]. On the face and the anterior aspect of the neck, the “nevus lines” were, for similar reasons, drawn in a rather cursory way (Fig. 5.4). One hundred years later, these blank areas were filled in by use of 187 relevant figures collected from the literature (Fig. 5.8a–c) [33]. On the face the lines of Blaschko show a sandglass-like arrangement converging on the nasal root. Remarkably, however, a definite crossing of lines, sometimes even at an angle of 90°, was noted. Apparently, the direction of embryonic movements varies on the head to a large degree. So far it is unclear whether different skin disorders give rise to such different linear patterns.

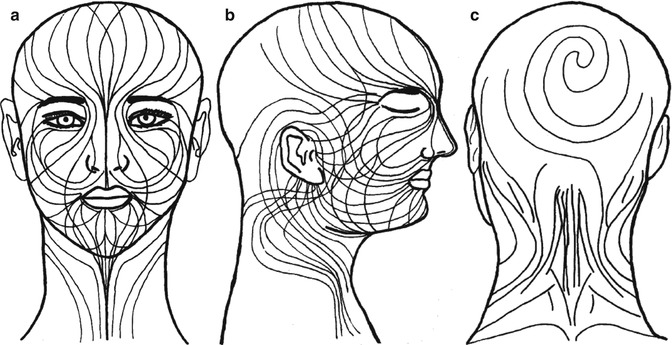

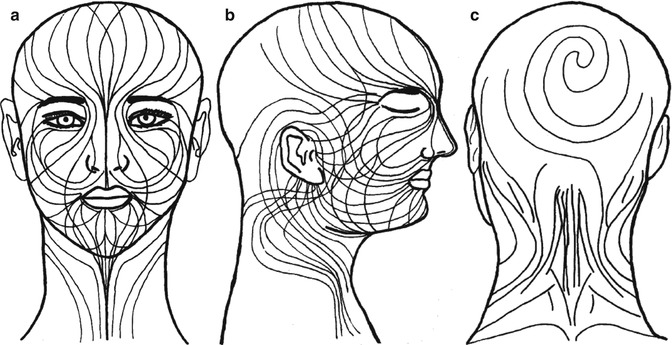

Fig. 5.8

Lines of Blaschko on the head and neck. (a) Frontal view; (b) lateral view; (c) dorsal view [33] (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Limited, UK)

It has been argued that the lines of Blaschko are of epidermal origin and thus may exclusively reflect genes expressed in keratinocytes or melanocytes [54, 55]. If so, it would be difficult or even impossible to explain the linear patterns of primarily mesodermal disorders such as focal dermal hypoplasia (see Sect. 12.1.2), linear atrophoderma of Moulin [13], or linear progressive fibromatosis [49, 65]. One may resort to the auxiliary hypothesis that these dermal defects occur under the control of the keratinocytes, but it is far more likely that the primordial skin fibroblasts proliferate and migrate in a way similar to that of the epidermal precursor cells. Future research will show which view is correct.

The lines of Blaschko often reflect epigenetic mosaicism. In this form the linear pattern can be inherited from one generation to the next one. A classical example is the Lyon effect of X inactivation giving rise to linear skin lesions in incontinentia pigmenti, focal dermal hypoplasia, Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, and many other X-linked phenotypes (see Sect. 12.1). On the other hand, familial cases of linear hyperpigmentation suggesting autosomal epigenetic mosaicism have likewise been found. Such cases can be best explained by monoallelic expression of an autosomal pigmentary gene (see Sect. 3.2.1).

The concept that Blaschko’s lines reflect the clonal outgrowth of embryonic cells (Fig. 5.7) is today still refused by some authors [20]. By suggesting an analogy between Blaschko’s lines and the stripes of zebras or zebra fish, Gilmore [21] assumed that all nevi are secondary to “chemical prepatterns” produced by a “reaction–diffusion process”: “The distribution of the nevus over the skin will be independent of the presence of the abnormal clone, but not of the presence of the activated gene of the abnormal clone… Finally, the chemical prepattern may be the trigger for a spatially dependent selective proliferation of one cell type over another. An interesting hypothesis is that the pattern-forming process itself may be pathological, so that in people unaffected by naevoid skin disease the lines of Blaschko do not exist” [20]. Conversely, we concur with Alfred Blaschko that his “nevus lines” do likewise exist in normal individuals. The occurrence of acquired linear skin disorders such as linear psoriasis or linear lichen planus provides convincing evidence that Gilmore’s hypothesis cannot be true. The lines of Blaschko are invisibly present throughout life in the form of a “spatial prepattern.” This view is also supported by the brindle patches as noted in American bulldogs (Fig. 5.9).

Fig. 5.9

American bulldog with brindle patches, indicating that the lines of Blaschko are invisibly present in the skin of all mammals (Photo by sannse, Creative Commons)

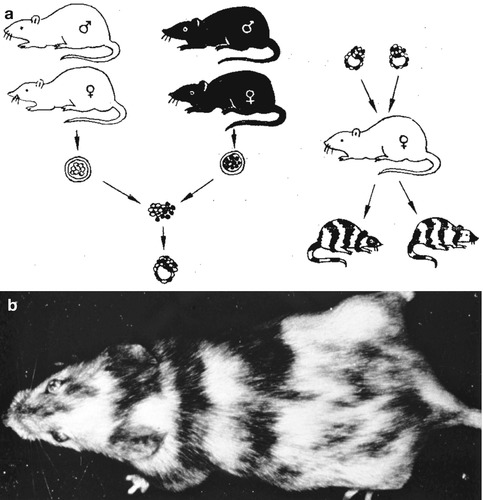

Coat patterns that are, to some degree, reminiscent of Blaschko’s lines have been described in X-linked murine traits [10] and in chimeric mice (Fig. 5.10) [52] or in transgenic animals [44]. On the other hand, the brindle trait of dogs is an exact counterpart of the human lines of Blaschko (see Sect. 3.2.1) [11, 34, 41].

Theoretically, a systematized pattern of Blaschko’s lines may also be explained by a gametic half-chromatid mutation [47], but this mechanism is less likely and has so far not been proven.

For heuristic purposes, two subtypes of Blaschko’s lines characterized by either narrow bands (“type 1a”) or rather broad bands (“type 1b”) have been separated. This somewhat artificial distinction appears to be useful, but at this point in time, we should still be open for other approaches of subclassification.

5.1.1 Lines of Blaschko, Narrow Bands

This archetypical pattern is followed by many hereditary or nonhereditary skin disorders that are reviewed in detail in Part III. Usually, the pattern of Blaschko’s lines is easily discernible (Fig. 5.11) [7]. Sometimes, epidermal nevi being systematized along these lines may also involve the oral mucosa (Fig. 5.12). In a sebaceous nevus, the narrow bands may by chance be contiguous in some regions, giving rise to a large plaque of nonlinear appearance, especially on the scalp (Fig. 5.13).

Fig. 5.11

Systematized sebaceous nevus following Blaschko’s lines (Courtesy of Dr. Mónica Zambrano, Quito, Ecuador)

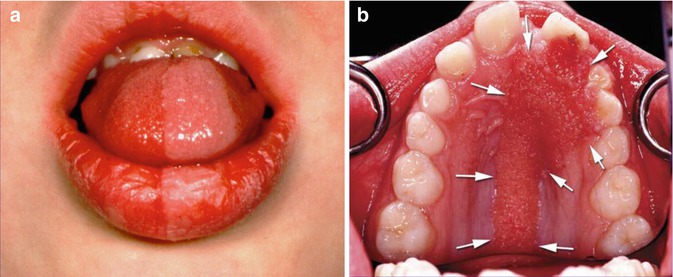

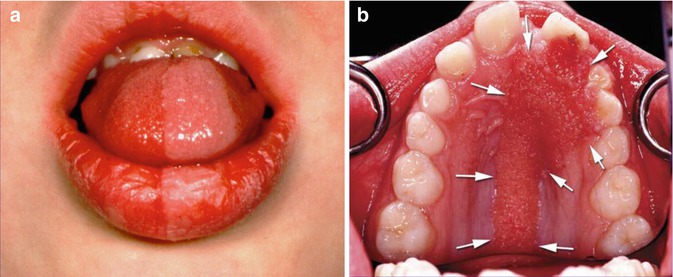

Fig. 5.12

Intraoral lesions following Blaschko’s lines in two boys with (a) systematized keratinocytic nevus and (b) facial nevus sebaceus. Arrows indicate the borders of the nevus [70] (a: Courtesy of the late Dr. Robert J. Gorlin, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA; b: Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Limited, UK)

Fig. 5.13

Scalp involvement of a child with nevus sebaceous. In this particular area, the segmental lesions may be broad to such degree that a linear pattern is no longer discernible

5.1.2 Lines of Blaschko, Broad Bands

A classical example of this subtype is the pigmentary disorder associated with McCune-Albright syndrome [31]. The segmental light-brown macules are broad to such degree that the linear pattern is sometimes difficult to identify. It seems not justified, however, to say that the pattern of Blaschko’s lines is only “occasionally observed in the McCune-Albright syndrome” [20]. On the contrary, it should be borne in mind that this archetypical pattern is virtually always present in that disorder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree