(1)

Department of Dermatology, Freiburg University Medical Center, Freiburg, Germany

Abstract

Among the skin disorders reflecting mosaicism, two major categories are genomic mosaics and epigenetic mosaics. In genomic mosaicism we can discriminate lethal from nonlethal mutations. Lethal mutations can only survive in a mosaic state. By contrast, nonlethal mutations, when transmitted to the next generation, cause a diffuse, nonmosaic involvement. – A type 1 segmental manifestation reflects a postzygotic mutation occurring in an otherwise healthy embryo, whereas a type 2 segmental manifestation is superimposed on a diffuse, nonsegmental involvement and reflects loss of the corresponding wild-type allele occurring in a heterozygous embryo. – In common polygenic skin disorders such as psoriasis a pronounced, superimposed segmental manifestation may originate form early loss of heterozygosity or from a postzygotic new mutation occurring at an additional predisposing gene locus. – In paradominant traits, heterozygous individuals are usually healthy. The disorder only becomes manifest when the corresponding wild-type allele is lost at an early developmental stage, giving rise to a homozygous or hemizygous patch. – Twin spots are paired patches that differ genetically from each other and from the surrounding background tissue. In human skin, possible examples are cutis tricolour and paired nevus flammeus and nevus anemicus. – In epidermolysis bullosa and other genodermatoses, revertant mosaicism may result from a postzygotic back mutation, giving rise to patches of healthy skin. Epigenetic mosaicism of autosomes has been studied in dogs and may also occur in humans. Epigenetic mosaicism of X chromosomes results in a linear or otherwise segmental pattern in various X-linked skin disorders. In some of these traits such as incontinentia pigmenti or focal dermal hypoplasia, X-inactivation accounts for survival of female embryos, whereas male embryos carrying the mutation usually die in utero. By way of exception, however, male embryos with a 46,XY karyotype may survive because they carry a postzygotic new mutation giving rise to genomic mosaicism, or because they have a 47,XXY karyotype resulting in functional X-chromosome mosaicism. – It should be borne in mind that not all of the X-linked human genes are inactivated. For example, the gene of X-linked recessive ichthyosis escapes inactivation, which is why female gene carries display a completely normal phenotype.

Among the mosaic skin disorders, two major categories in the form of either genomic or epigenetic mosaicism can be distinguished.

3.1 Genomic Mosaicism

Genomic mosaicism in human skin reflects the action of either autosomal or, by way of exception, X-linked genes. Most of the autosomal mosaics represent sporadic traits. By contrast, the rare cases of genomic mosaicism of an X-linked mutation occurring in a male imply that the mosaic trait can be transmitted to a daughter in the form of epigenetic mosaicism.

3.1.1 Genomic Mosaicism of Autosomes

Many human mosaics originate from a postzygotic autosomal mutation. For the purpose of genetic counseling, it is important to distinguish between lethal and nonlethal postzygotic mutations. If the underlying mutation acts as a lethal factor, the risk for the next generation is virtually nil, whereas children of a patient showing mosaicism of a nonlethal mutation run an increased risk that the same phenotype may diffusely affect their entire body.

3.1.1.1 Mosaicism Caused by Loss of Heterozygosity

In an individual heterozygous for an autosomal mutation involving the skin, postzygotic loss of the corresponding wild-type allele may result in a mosaic phenotype.

Both benign and malignant skin tumors can be taken as examples of cutaneous mosaicism. Most, if not all of them, originate from LOH. In a tissue heterozygous for a mutant allele predisposing to neoplastic growth, loss of the corresponding wild-type allele may give rise to a cell being either homozygous or hemizygous for the tumor gene. Remarkably, however, the traditional two-hit mechanism [31, 106] does not appear to be valid for all skin tumors. Already prior to the molecular era, statistical data obtained by theoretical mathematics indicated that this model was too simplistic for many hereditary malignant tumors [38, 39, 175], and a four-mutation model was proposed [39, 76]. More recent molecular studies have supported this view [25, 40, 60, 133, 163]. Other forms of multihit mechanisms are likewise possible [141].

Moreover, the concept of LOH appears to be a powerful tool to explain various other forms of cutaneous mosaicism such as the type 2 segmental manifestation of autosomal dominant skin disorders, paradominant inheritance, or didymosis (twin spotting).

3.1.1.2 Genomic Mosaicism of Lethal Autosomal Mutations

Some multisystem birth defects are caused by autosomal mutations that, when present in the fertilized egg, result in early intrauterine death of the embryo. Cells affected with such mutations can only survive in an admixture with normal cells, i.e., in a mosaic state that usually originates from an early postzygotic mutation. Theoretically, such mosaics may also develop from a gametic half-chromatid mutation [119], but this hypothesis is so far unproven and its practical significance is unclear.

Mosaicism Caused by Lethal Cytogenetic Abnormalities

A numerical aberration of chromosomes or parts of a chromosome has been found in many cases of cutaneous mosaicism. In 1983, Chemke et al. [26] reported on a linear hypermelanosis reflecting trisomy 18 mosaicism. Subsequently, other authors found various types of numerical chromosome aberrations in patients with pigmentary mosaicism of the hypermelanotic type [111] or of the Ito type being characterized by hypomelanotic bands following Blaschko’s lines [114]. More rarely, lethal cytogenetic aberrations have been found in the tissue of epidermal nevi [170, 172] or systematized blaschkitis [123].

Mosaic partial trisomy 13q causes a distinct neurocutaneous phenotype in the form of phylloid hypomelanosis [56]. In its nonmosaic form, trisomy 13 is a “sublethal” chromosome aberration, which means that children with this cytogenetic disorder usually die during early infancy, whereas some of them may reach adolescence or even adulthood [22].

Mosaicism Caused by Lethal Molecular Defects

Some mosaic skin disorders exclusively occur sporadically because the underlying mutation, when present in the zygote, acts as a lethal factor [65, 66]. In the developing embryo, cells carrying the mutation can only survive in a mosaic state, in close vicinity to the normal cell population. The hypothesis has now been corroborated by several molecular studies (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

Mosaic phenotypes reflecting lethal autosomal mutations confirmed at the molecular level

Disorder | OMIM number | Reference | Section number in this book |

|---|---|---|---|

CLOVES syndrome | 612918 | ||

FGFR3 epidermal nevus syndrome (García-Hafner-Happle syndrome) | No specific entry (see 162900) | ||

Megalencephaly-livedo reticularis congenita syndrome (“macrocephaly-capillary malformation syndrome”) | 602501 | [153] | |

McCune-Albright syndrome | 174800 | ||

Maffucci syndrome | 614569 | ||

Papular nevus spilus syndrome | No entry | ||

Proteus syndrome | 176920 | ||

Schimmelpenning syndrome, including phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica | 163200 | ||

Sturge-Weber syndrome | 185300 |

A similar etiology has been proposed for many other mosaic traits that occur sporadically, such as Becker nevus syndrome, nevus comedonicus syndrome, encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis, and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita [73, 79] (Table 3.2). Sturge-Weber syndrome is most likely a cephalic manifestation of Sturge-Weber-Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (see Sect. 7.4.1.1).

Table 3.2

Other mosaic phenotypes suggesting the action of a lethal mutation surviving by mosaicism

Disorder | OMIM number | Reference | Section number in this book |

|---|---|---|---|

Angora hair nevus syndrome (Schauder syndrome) | No entry | [160] | |

Becker nevus syndrome | 604919 | [89] | |

Castori syndrome | No entry | [23] | |

Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (Van Lohuizen syndrome) | 219250 | ||

Delleman syndrome | 164180 | [66] | |

Encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis | 613001 | [91] | |

NEVADA syndrome | No entry | [87] | |

Nevus comedonicus syndrome | No entry | [68] | |

Nevus trichilemmocysticus syndrome | No entry | [87] | |

Pigmentary mosaicism of the Ito type | 300337 | [73] |

Delleman syndrome is a characterized by a triad of ocular, neurological, and cutaneous defects. Major features include orbital cyst, eyelid coloboma, porencephaly, cranial defects, periorbital skin tags, and multiple patchy aplastic skin lesions. The phenotype always occurs sporadically and shows a mosaic, asymmetrical arrangement of lesions, which is why the action of a lethal gene is rather likely [66].

In most cases of pigmentary mosaicism of Ito, cytogenetic analysis reveals a normal karyotype in all samples examined. Such cases can best be explained by a postzygotic point mutation or intragenic deletion that cannot be detected with the techniques so far available.

3.1.1.3 Genomic Mosaicism of Nonlethal Autosomal Mutations

According to formal genetics, we can discriminate, in autosomal dominant skin disorders, three different types of mosaicism.

Three Categories of Mosaicism of Nonlethal Mutations

In a type 1 segmental involvement, the remaining skin is healthy. By contrast, a type 2 segmental manifestation is rather pronounced and superimposed on the nonsegmental disorder, which means that the remaining skin is affected to a degree as noted in the ordinary, nonmosaic phenotype. This dichotomy of mosaic manifestations is important for genetic counseling because in the type 2 segmental involvement the next generation runs a 50 % risk of occurrence of the nonsegmental trait, whereas in the type 1 this risk is much lower.

A third category of mosaicism develops at a later stage of fetal development or during postnatal life. It is by far the most common type of mosaicism occurring in autosomal dominant traits and consists in a nonsegmental, disseminated arrangement of neoplastic or nonneoplastic skin lesions. For example, all neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules of neurofibromatosis 1 reflect the clonal outgrowth of cells having lost, at the NF1 locus, the corresponding wild-type allele [51]. An unusual form of disseminated revertant mosaicism as noted in ichthyosis in confetti (ichthyosis variegata) [29] does likewise belong to this common category.

Type 1 Segmental Manifestation of Autosomal Dominant Traits

A segmental involvement associated with otherwise unaffected skin has been described in many autosomal dominant genodermatoses such as neurofibromatosis 1 [178], tuberous sclerosis [3, 134, 186], epidermolytic ichthyosis of Brocq [145], Hailey-Hailey disease [94], syringomatosis [200], Darier disease [157], and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [34, 110].

It is important to realize that a type 1 segmental manifestation may involve, by way of exception, most parts of the integument, leaving only small segments of the skin unaffected (Fig. 3.1) [185].

Fig. 3.1

This 38-year-old woman had lesions of neurofibromatosis 1 throughout her body but leaving a few segmental areas unaffected. Molecular proof of a postzygotic new mutation was provided by the authors [185]

Practical Aspect: A type 1 segmental involvement may imply gonadal mosaicism (Fig. 3.2). Therefore, patients with a type 1 segmental manifestation run an increased risk to give birth to children affected with a nonsegmental form of the same trait. Most likely, this risk will increase with the degree of segmental involvement as present in the parent.

Fig. 3.2

The term “somatic mosaicism” is often used in a misleading way because it refers to only one of three possibilities. A postzygotic mutation may affect both somatic and gonadal tissues (left) or somatic tissue alone (middle) or gonadal tissue alone (right)

Type 2 Segmental Manifestation of Autosomal Dominant Traits

Until the end of the twentieth century, the theory prevailed that mosaic forms of autosomal dominant skin disorders originated from postzygotic new mutations. Today, this concept is no longer valid [74]. Sometimes, the mosaic involvement is very pronounced and may be superimposed on a milder, diffuse manifestation of the same phenotype [137]. Such cases may be best explained by loss of the corresponding wild-type allele occurring at an early developmental stage, giving rise to a mosaic cell clone being either homozygous or hemizygous for the underlying mutation [70]. Based on this concept the rule of dichotomous types of segmental manifestation was developed (Fig. 3.3) [75, 77]. The major differences between the two types of segmental involvement are summarized in Table 3.3.

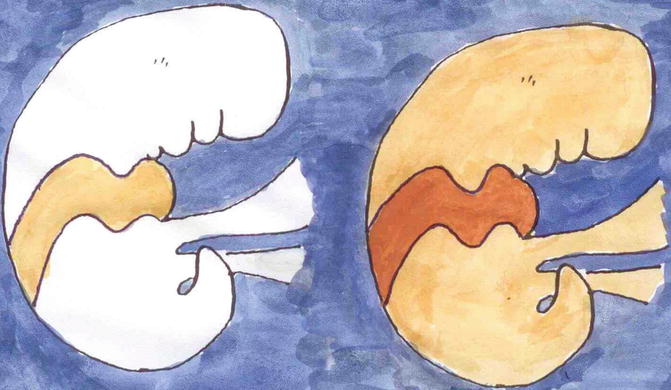

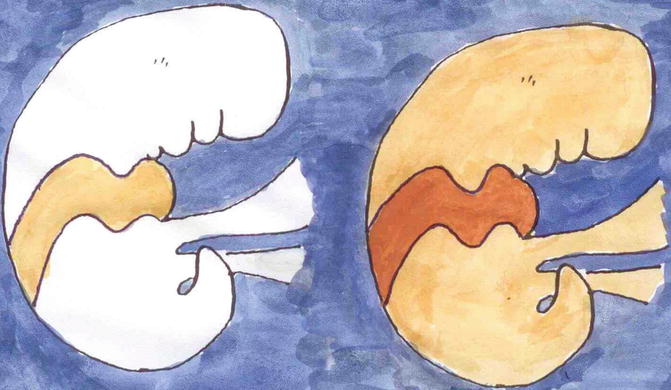

Fig. 3.3

Dichotomous types of mosaicism as noted in autosomal dominant skin disorders. In a healthy embryo, a postzygotic new mutation gives rise to a type 1 segmental involvement reflecting heterozygosity (left). In a heterozygous embryo, an early event of loss of heterozygosity may cause a type 2 segmental involvement being far more pronounced and superimposed on the nonsegmental phenotype (right)

Table 3.3

Differences between type 1 and type 2 segmental manifestations of autosomal dominant skin disorders

Type 1 segmental manifestation | Type 2 segmental manifestation |

|---|---|

Originates from a new mutation occurring in a healthy embryo | Originates in a heterozygous embryo |

Reflects heterozygosity | Reflects loss of heterozygosity |

Becomes manifest at an age when the nonsegmental phenotype would appear | Becomes manifest much earlier than the nonsegmental phenotype |

Degree of involvement corresponds to that of the nonsegmental phenotype | Degree of involvement is very pronounced and superimposed on the ordinary trait |

The type 2 segmental manifestation should not be taken as a rarely occurring oddity. Rather, it reflects a general rule that can be observed in almost all autosomal dominant skin disorders.

Some clinical examples are summarized in Tables 3.4 and 3.5. The concept has so far been proven at the molecular level in several disorders such as Hailey-Hailey disease [149], PTEN hamartoma syndrome [82], and Darier disease [46]. Molecular corroboration in other autosomal dominant skin disorders can be expected in the near future.

Table 3.4

Autosomal dominant skin disorders with type 2 segmental manifestation confirmed at the molecular level

Disorder | OMIM number | Reference | Section number in this book |

|---|---|---|---|

Hailey-Hailey disease | 169600 | [149] | |

Legius syndrome | 611431 | ||

PTEN hamartoma syndrome (Cowden disease included) | 158350 | [82] | |

Neurofibromatosis 1 | 162200 | [171] | |

Darier disease | 124200 | [46] | |

Gorlin syndrome | 109400 | [181] |

Table 3.5

Autosomal dominant skin disorders showing a type 2 segmental involvement that is so far unproven at the molecular level

Disorder | OMIM number | Section number in this book |

|---|---|---|

Acanthosis nigricans | 100600 | |

Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy | 103580 | |

612463 | ||

Basal cell carcinoma, nonsyndromic hereditary multiple | 605462 | |

Basaloid follicular hamartoma, multiple | 605827; 604451 | |

Blue rubber bleb angiomatosis | 112200 | |

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome | 166700 | |

Dyskeratosis congenita, autosomal dominant | 127550; 613989;613990 | |

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, type III | 130020 | |

Epidermolytic ichthyosis of Brocq | 113800 | |

Glomangiomatosis | 138000 | |

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | 187300 | |

Hornstein-Knickenberg syndrome (alias Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome) | 135150 | |

KID syndrome | 148210 | |

Leiomyomatosis, cutaneous | 150800 | |

Neurofibromatosis 2 | 101000 | |

Osteomatosis cutis, hereditary | 166350 | |

Porokeratosis, disseminated superficial actinic | 175900; 607728;612293 | |

Porokeratosis of Mibelli | 175800 | |

Porokeratosis palmaris, plantaris et disseminata | 175850 | |

Trichoepithelioma, multiple | 601606; 605041;612099 | |

Tuberous sclerosis | 191100; 631254 | |

Spiradenoma, multiple | 605018; 605041 | |

Syringoma, multiple | 186600 |

A list of historical terms that were used to describe what can today be categorized as type 2 segmental manifestations is presented in Table 3.6. During the years to come, such descriptive wording should alert the readers that, in fact, a type 2 segmental involvement may have been overlooked. One descriptive term, “progressive osseous heteroplasia,” has even got its own OMIM number 166350, although it merely represents a pronounced mosaic manifestation of the autosomal dominant trait, hereditary osteoma cutis [142].

Table 3.6

Historical descriptive words or phrases heralding a type 2 segmental manifestation of autosomal dominant skin disorders

Name of disorder known to show a type 2 segmental involvement | Historical descriptive terms referring to type 2 segmental lesions |

|---|---|

Acanthosis nigricans | Acanthosis nigricans form of epidermal nevus [44] |

Albright hereditary osteodystrophy | Progressive osseous heteroplasia [165] |

Sharply demarcated zone of subcutaneous and dermal hypoplasia with subcutaneous calcifications [104] | |

Blue rubber bleb angiomatosis (“blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome”) | Huge angiomatous cutaneous mass [138] |

Massive pelvic hemangioma [7] | |

Lymphangiomatosis-like growth pattern within the uterus [147] | |

Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome | Juvenile elastoma [6] |

Forme fruste of Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome [47] | |

Darier disease | Unilateral, linear, zosteriform epidermal nevus with acantholytic dyskeratosis [37] |

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type III | Connective tissue nevus (collagenoma) [166] |

Epidermolytic ichthyosis of Brocq | Naevus verrucosus hystricoides [61] |

Epidermal nevus [43] | |

Glomangiomatosis | Congenital plaque-like glomangioma [156] |

Giant glomangioma [167] | |

Giant congenital patch-like glomus tumors [197] | |

Congenital plaque-type glomuvenous malformations [128] | |

Hailey-Hailey disease | |

Hornstein-Knickenberg syndrome (alias Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome) | Large connective tissue nevus of shagreen plaque type with papular fibromas of the follicular sheath [192] |

Leiomyomatosis | Giant zoniform leiomyoma [21] |

Marfan syndrome | |

Neurofibromatosis 1 | |

Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis and plexiform neurofibroma [158] | |

Osteomatosis cutis, hereditary | |

Severe congenital platelike osteoma cutis [196] | |

Limited dermal ossification [48] | |

Porokeratosis, disseminated superficial actinic | |

Congenital linear porokeratosis [173] | |

Porokeratosis of Mibelli | “Linear lesions were said to have been present since birth” [11] |

Ulcerative systematized porokeratosis (Mibelli) [152] | |

PTEN hamartoma syndrome (Cowden disease included) | Proteus-like syndrome [201] |

Arteriovenous fistulas; “intramuscular vascular anomalies in our patients disrupted the muscular architecture and had excessive disorganized ectopic fat” [176] | |

“Hemimegalencephaly as part of Jadassohn nevus sebaceus syndrome” [135] | |

Rhodoid nevus syndrome (“capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation”) | Arteriovenous malformation [12] |

Spiradenomatosis | Congenital linear eccrine spiradenoma [155] |

Congenital blaschkoid eccrine spiradenoma [41] | |

Syringomatosis | Plaque-like syringoma [101] |

Linear syringomatous hamartoma [194] | |

Localized form, clinical variant “en plaque” [129]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|