8.4 Short scar periareolar inferior pedicle reduction (SPAIR) mammaplasty

Evolution of technique

In evaluating other techniques designed to reduce the scar burden associated with breast reduction, two contrasting methods stand out. First, based on the work of Benelli,1 attempts to limit the scar to just the periareolar area have been described. Here the inherent “dog-ear” that is created by the use of a large periareolar incision and a smaller areolar incision places great stress on the subsequent skin closure. Therefore, while the scar can be limited to just the periareolar incision when this technique is used, severe drawbacks include compromise of the size, shape, and position of the areola, stippling and irregularity in the periareolar scar, and shape distortion with flattening of the breast itself. As a result, this technique can be reliably utilized only in small reductions of 200 g at most and where the skin envelope is only minimally redundant. In contrast to strictly periareolar techniques stands the classical vertical mammaplasty of Lassus and Lejour.2–10 Here, the defect created for the NAC is designed to more or less match the dimensions of the incision made around the areola. As a result, the inherent “dog-ear” that is created with the application of the vertical segment is entirely limited to the area between the inferior portion of the areola and the inframammary fold. For a breast of any size, the stress placed on this portion of the breast both in scar quality and healing can be significant. As well, because the parenchymal removal is performed in the inferior pole of the breast, not only is the internal scaffold of the breast disrupted but the entire inframammary fold is released. As a result, and as with the inverted T approach, the breast will “bottom out” or change shape over time. In fact, it is commonly recommended that the shape of the breast appears significantly distorted at the end of the procedure such that the upper pole is overfilled and the lower pole appear flattened in preparation for this shape change to take place. Therefore, rather than eliminating bottoming out as has been claimed by some, the final result actually depends on bottoming out to create the final breast shape. Another significant drawback related to limiting the skin removal to the vertical segment involves the final shape of the breast. For larger breast reductions, plicating the lower pole of the breast in a vertical fashion from the areola down to the fold simply results in a vertical scar that is too long. The distance from the areola to the fold becomes excessive and the breast appears “bottomed out” with a nipple position that is too high. As well, due to irregular tissue approximation at the level of the inframammary fold (IMF), wound breakdown, unsightly scars, and shape distortion can also occur. Often times, these complications become manifest only when the patient raises her arms over shoulder level. In an attempt to manage this aspect of the pattern, various strategies for creating scar contracture at the level of the fold have been described including the use of purse-string sutures and aggressive liposuction however these issues continue to be responsible for many revisions in patients undergoing vertical mammaplasty. For these reasons, the vertical mammaplasty is best applied to smaller breast reductions of ≤400 g. Using the technique in larger patients may risk unfavorable results with an unacceptably high revision rate.

Despite the disadvantages associated with these various procedures, there are very effective strategic design elements of each that can be combined to provide a versatile and widely applicable technique of breast reduction. From the inverted T experience comes the reliability noted with the use of the inferior pedicle to maintain the vascularity of the NAC even in extreme circumstances. Also, by keeping this centrally located mound of tissue directly under the NAC, the shape of the breast can be better controlled and very importantly, the dissection can be modified to allow the structure of the IMF to remain intact. From the periareolar experience comes the realization that the size of the periareolar incision can exceed that of the areolar incision up to point and still provide a controlled and aesthetic periareolar shape and scar. From the vertical experience comes the observation that the addition of a vertical segment to the skin pattern is a powerful and effective shaping maneuver that can offset the disadvantages associated with purely periareolar techniques. Therefore by using an inferior pedicle technique for management of the vascularity to the NAC with a combined and slightly modified vertical and periareolar or circumvertical skin pattern, the dog-ear inherent in the skin envelope management strategy is distributed over the entire incision as opposed to just around the areola (i.e., Benelli) or just to the vertical segment (i.e., vertical mammaplasty). The result is a very effective, reliable, and widely applicable technique for breast reduction. This is the basis for the SPAIR procedure.11–14

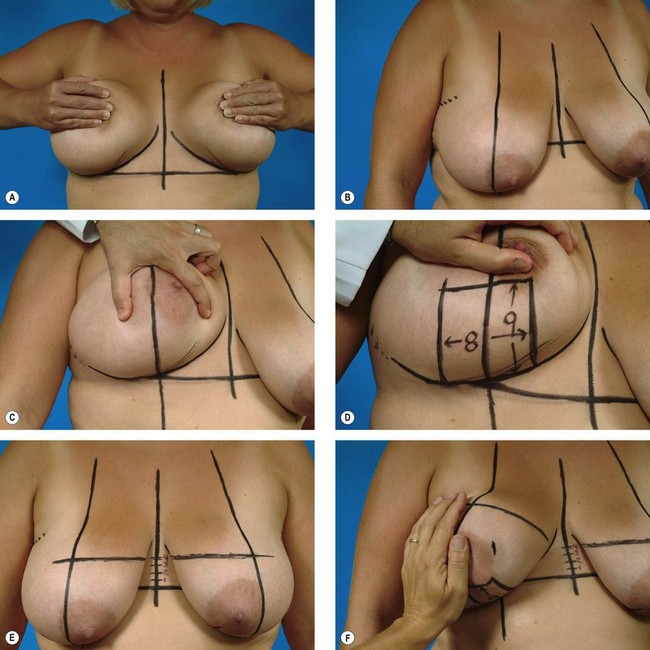

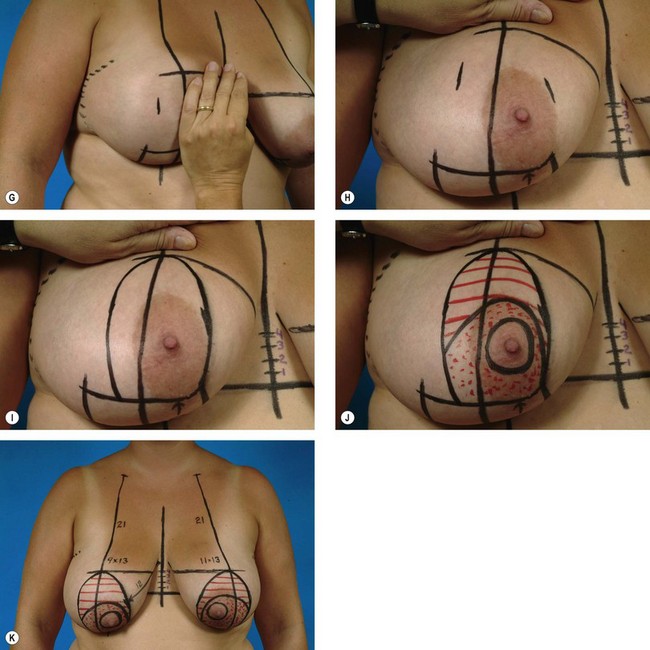

Surgical planning and marking

The patient is marked in the upright position. Basic landmarks, including the location of the inframammary fold, the breast meridian, and the midsternal line are drawn in. By communicating the level of the inframammary fold across the midline, the location of the fold can be directly seen without the need to manipulate the breast and potentially skew the apparent location of the fold. An 8 cm pedicle is diagrammed on the lower pole of the breast centered on the breast meridian. Measuring up from the inframammary fold on either side of the pedicle a distance of 8–10 cm is measured and then marked. For smaller reductions, the 8 cm measurement is used with the 10 cm measurement being used for larger reductions. Communicating these points identifies the lower portion of the periareolar pattern. The top of the periareolar pattern is drawn 4 cm above the inframammary fold line. This means that the nipple will be located 2 cm above the fold. This is the desired location given that the location of the fold will not change as a result of the dissection. To artificially position the NAC in any other location in an attempt to accommodate for suspected changes in the shape of the breast is unnecessary and will risk NAC malposition. To determine then the medial and lateral extent of the periareolar pattern, the breast is transposed first up and out and then up and in and the breast meridian is ghosted onto the newly transposed breast at the level of the nipple. The four cardinal points of the pattern are then joined with a smooth line and the inferior pedicle is drawn in skirting the top of the periareolar pattern by a distance of 2 cm. This completes the marking process (Fig. 8.4.1).