Secondary Prosthetic Cases

Scott L. Spear

M. Renee Jespersen

Adam D. Schaffner

By its very nature, breast reconstruction is often a staged procedure requiring two, three, or more steps over a period of many months to achieve a successful outcome. The necessary components include creating a breast mound, achieving symmetry, reconstructing the nipple, and permanently coloring the nipple and areola. Along this path of reconstruction, the surgeon also has the opportunity to revise or revisit earlier phases of the reconstruction process even as the next stage is being undertaken. When talking to patients, we often liken breast reconstruction to a sculpture or an oil painting, where it is well accepted that repeated refinements are necessary to achieve something worthwhile. The episodic popularity of one-stage breast reconstruction, although valid in the occasional patient, is worrisome because of its implication that consistent results can or should be achieved in one step. As more patients choose prophylactic surgery, and as implants and reconstructive techniques improve, the expectations of some patients have risen to near the level of cosmetic surgery. While this is not always realistic, we are frequently able to deliver excellent results, sometimes through multiple refinements. While this chapter focuses on reconstructive cases, the same techniques can frequently be applied to any secondary implant case. The figures in this chapter illustrate our most frequently used techniques, and frequently multiple techniques are used in each patient.

Whether completing the prosthetic breast reconstruction of one’s patient or inheriting that of another surgeon, the second or later stages in prosthetic breast reconstruction are often the most challenging and complex. This chapter focuses on common problems seen in patients during or after breast reconstruction using breast implants. Common problems include capsular contracture around the implant or expander, implant malposition, inframammary fold malposition or absence, inadequate or malpositioned nipple-areola reconstruction, and implant problems such as rupture, rippling, and improper size or shape. Management of these patients includes proper diagnosis of the problem(s) and planning of the necessary steps for correction.

If the problem is simply device deflation or rupture, then the solution is straightforward. Recreation of the inframammary fold is discussed as a separate issue in Chapters 41 and 42. This chapter thus concentrates on capsular contracture, nipple-areola problems, device problems (such as malposition, rippling, and improper implant selection), and tissue coverage and contour problems. When evaluating these patients, it is important to review the previous operative records and the current physical findings. In assessing each patient, there are several issues to consider:

Was a prosthetic reconstruction a realistic plan initially?

If so, is it a still a good plan, or has there been an intervening event (e.g., radiation or infection)?

Was an appropriate implant chosen?

Is the implant appropriately positioned?

Does the contralateral breast need alteration to improve symmetry?

Are there contour problems detracting from the result?

Is the nipple adequately reconstructed and/or properly positioned?

In determining whether an implant reconstruction is currently an appropriate option, the tissue quality and history of infection or radiation are important factors. Radiation is one of the most common factors compromising tissue quality in implant reconstruction. Less commonly, infection can damage tissue and render it unsuitable to accommodate an implant. Recurrent infection can also make an implant reconstruction untenable. For a more in-depth discussion of the risks of implant reconstruction in the setting of radiation, refer to Chapter 49 on prosthetic reconstruction in the radiated breast.

Choosing An Appropriate Implant

An implant of appropriate shape and size will have the correct diameter to fit the patient’s chest as well as a volume that fits her body shape and habitus. An implant that is sized poorly in either of these aspects will appear unnatural. Careful implant selection is even more important in the patient having a nipple-sparing mastectomy. The reconstructed mound works best when it mimics the original breast footprint on the chest wall or the retained nipple risks being out of place. (Should other factors cause a malpositioned nipple, repositioning techniques are discussed later in this chapter.) Patients with thinner tissue envelopes and less subcutaneous fat tend to have more problems with visibility of implant edges and rippling (Figs. 40.1 to 40.3). They seem to get a better result with contoured and/or silicone implants for this reason. Fat grafting is a useful tool for camouflaging contour irregularities associated with a thin soft tissue envelope and is likewise addressed later in this chapter and in depth in other chapters in this text dealing with fat grafting. While these methods can help address some implant reconstruction problems, none will replace choosing an appropriately sized implant. In the case in which a major change in implant size or volume is needed, we have often returned to a tissue expander as a first stage to establish adequate coverage, then placed the new implant in a second procedure.

Appropriate Position

Small implant position changes in almost any direction can be achieved with either a simple capsulotomy or strip capsulectomy or with a capsulorrhaphy with permanent suture. Significant malposition, capsular contracture, or malposition that is prone to relapse (such as synmastia) can be corrected with a total capsulectomy or with the neosubpectoral

pocket technique (Chapter 124) (Figs. 40.4 to 40.9). The neosubpectoral technique has been particularly effective at correcting capsular contracture when a total capsulectomy would be difficult or undesirable. Techniques for altering or recreating an inframammary fold can be found in detail in the chapters on the neosubpectoral technique and the chapters on external and internal creation of the inframammary fold.

pocket technique (Chapter 124) (Figs. 40.4 to 40.9). The neosubpectoral technique has been particularly effective at correcting capsular contracture when a total capsulectomy would be difficult or undesirable. Techniques for altering or recreating an inframammary fold can be found in detail in the chapters on the neosubpectoral technique and the chapters on external and internal creation of the inframammary fold.

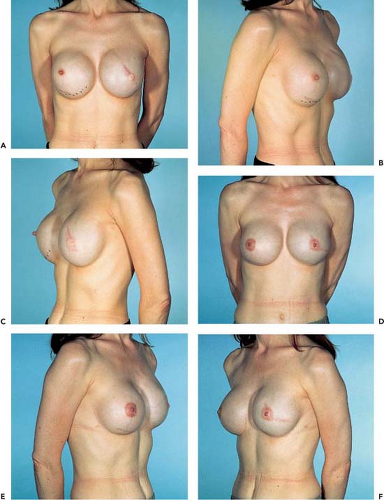

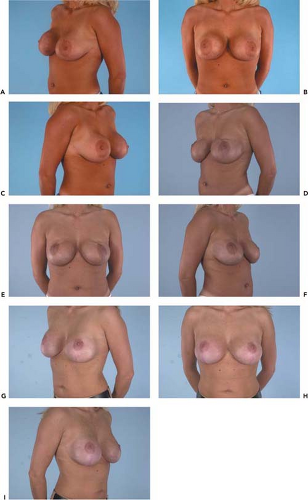

Figure 40.2. A–C: A 32-year-old woman with bilateral breast augmentation prior to bilateral prophylactic mastectomies. D–F: After bilateral subcutaneous mastectomies and staged reconstruction with Allergan style 153 implant textured anatomic silicone, showing evidence of visible rippling, upper pole volume deficit, and bottoming out. G–I: After revision consisting of bilateral mastopexy, exchange to 600-cc round silicone gel implants, and bilateral upper pole fat injection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|