31 Sacral Neuromodulation Therapy

Sacral neuromodulation, the focus of this chapter, involves the stimulation of the pelvic plexus and pudendal nerves that innervate the bladder, pelvic floor muscles, and rectum. Several theories about the mechanism of action have been proposed but remain largely uncertain. Electrical stimulation may modulate reflex pathways involved in both the storage and emptying phases of the micturition cycle, as reviewed by Koldewijn et al. (1994).

PATIENT EVALUATION

Beginning with a thorough history and physical examination, the evaluation for neuromodulation therapy for lower urinary tract dysfunction is no different than the evaluation for all patients with unresponsive and refractory lower urinary tract dysfunction. Salient features of the history and physical examination are listed in Box 31-1. In addition to a bladder diary, patients are asked to respond to two self-administered questionnaires—urogenital distress inventory, short form (UDI-6), and the incontinence impact questionnaire, short form (IIQ-7)—such that subjective improvement or progression with treatment can be monitored routinely.

BOX 31-1 SALIENT FEATURES OF THE INITIAL EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH LOWER URINARY TRACT DYSFUNCTION

Sacral neuromodulation is frequently attempted in patients who have failed traditional conservative measures, such as bladder retraining, pelvic floor biofeedback, and medications, but is done before more invasive surgical procedures, such as enterocystoplasty or urinary diversion. Despite all of the research done to date, no defined preclinical factors, such as urodynamic findings, can predict which patients will or will not have improvement after sacral neuromodulation.

OVERVIEW OF THE PROCEDURE

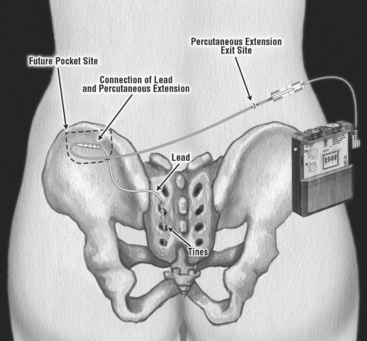

The procedure is performed in two stages. Stage I is a clinical trial of a temporary or permanent lead for external stimulation, and stage II is the implantation of a subcutaneous implantable pulse generator (IPG). Each stage can be done using monitored anesthesia supplemented with local anesthesia. During the initial introduction of InterStim neuromodulation therapy, patients underwent a percutaneous nerve evaluation (PNE) by the placement of a unilateral percutaneous lead in the S3 foramen, using local injectable anesthesia. The lead was connected to an external pulse generator and worn by the patient for several days. A large number of false-negative results are attributed to improper lead placement and migration. Although some physicians still prefer to perform the first stage using a PNE approach, most have adopted a permanent lead placement for the first stage (Fig. 31-1) in an attempt to avoid the issues related to high false-negative results with the first stage and high false-positive results with the second stage.

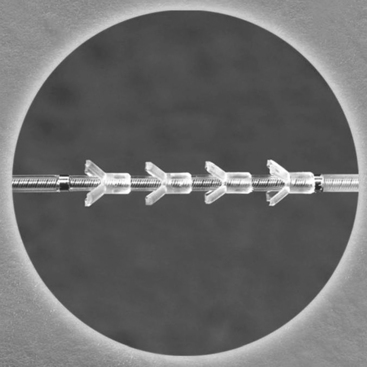

Figure 31-1 Permanent lead placement using a plastic anchor instead of a tine lead for a stage I trial.

(Reprinted with permission of Medtronic, Inc. © 2006.)

After lead placement, changes in lower urinary tract symptoms and postvoid residual volumes are recorded in a detailed bladder diary. If improvement is minimal or absent, revision or bilateral percutaneous lead placement may be attempted. If greater than 50% improvement in symptoms is attained, a permanent IPG is implanted. Examples of symptoms that should show measurable improvement for each indication are given in Box 31-2. The length of the trial with the external pulse generator may vary slightly from patient to patient, by the indication and by surgeon practice preference. In our experience with patients with urgency-frequency syndrome and urge incontinence, a 2- to 3-week trial is generally adequate. For urinary retention, a longer trial of 3 to 4 weeks may be necessary before obtaining a desired clinical response.

Previous lead placement required a more time-consuming surgical dissection of the layers above the sacral foramina and had unreliable lead fixation with anchors (see Fig. 31-1). Recent technical advances have made implantation of the percutaneous lead easier and less prone to migration. Spinelli et al. (2003) were the first to present their experience using the tine lead neuroelectrode (TNE; Fig. 31-2) for the Medtronic sacral nerve stimulator that used a percutaneous approach for placement and fixation. They reported on 15 patients who underwent stage I of the procedure, with 12 patients subsequently undergoing implantation of the pulse generator. No observation of lead displacement occurred during the screening period or during a mean follow-up of 11 months in the patients implanted with an IPG. Our initial experience in over 167 patients with tine lead confirms that the lead is less prone to migrate and results in fewer false-negative results with the screening trial. Furthermore, the false-positive rate of the screening trial is reduced. Placement of a permanent lead with reliable fixation during the screening trial ensures that the same location of stimulation is achieved when the IPG is implanted. With use of a PNE, or similar temporary lead electrode during the screening trial, a different clinical outcome may occur when the permanent lead is placed at the time of the IPG implantation.