The Role of Distractions and Interruptions in Operating Room Safety

Keywords

• Operating room safety • Distractions • Interruptions • Human factors • Culture • Crew resource management • Teamwork • Signs

Typically, the operating room setting is predisposed to a multitude of distractions leading to a potential for errors. Distractions, lack of focus, poor communication, and not establishing or following standard procedures often lead to problems within any setting.1

Certainly, the 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report sounded a sentinel alarm about medical errors in the United States. Its report of approximately 98,000 hospital deaths occurring in US hospitals annually as a result of medical errors led to increased efforts at resolving system problems. Yet little progress has been made in preventing errors.2 There is a need to reduce errors by improving focus, by using teamwork, decision support, checklists, and other strategies exemplified by other industries such as the aviation industry.3 Specific conditions within the operating room workplace could be addressed to improve focus and help prevent system errors. “Systems” is a word that is broadly used but often not understood. An explanation of the basics of what makes up a system and how they work together may clarify.

Open systems

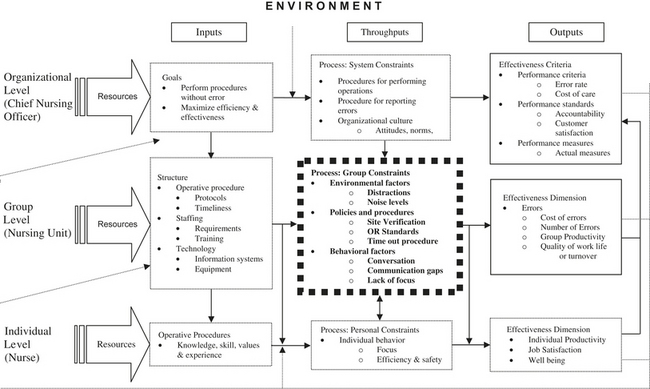

A system is a thing or an organization with interacting parts and subparts. Open systems theory is often used to diagnose system problems by looking at inputs, throughputs, and outputs. Health care organizations typically have open systems, because there are many department entities that interact with each other and with the outside world.4 Examples of operating room inputs are the characteristics and contributions of the perioperative nurses, technicians, physicians, patients, and tools involved in the surgical procedure. Throughputs are the system processes, organizational behavior, and patterns of interaction within the department. The output is the success of the service provided to the patient.5

The open system of the operating room is understandably in a constant state of flux in an attempt to balance the environment with organizational goals (Fig. 1). System problems hinder the process of getting things done. Once the problem areas are identified, interventions can be developed that resolve the most apparent and frequently occurring problems.6 In other words, identify the low hanging fruit and pick it first. These are also the areas that could be affected most easily and with lower-cost techniques.

Fig. 1 Operating room safety in hospitals: an organizational framework.

(Data from Pape TM. Applying airline safety practices to medication administration. Medsurg Nurs 2003;12(2):77–93.)

Group processes as a part of throughput include group members’ problem-solving techniques and collective beliefs and expectations. People in a group often choose to assist others only after seeking approval from peers, especially when it pertains to safety. However, education provides reasons and principles for changing behavior. Essentially people will listen and abide by rules when provided with rationale for the conduct.7 To that end, the perioperative nurse plays a key function as a role model in supporting the entire team.

Roles and functions in the operating room

Operating room settings are very demanding open systems that lend themselves to errors due to the nature of the environment and the fact that people are not perfect. Typically the staff skill mix and experience levels vary greatly, and there are numerous and complex functions expected of each person. Technological equipment and procedures are constantly evolving.1

The role of the perioperative nurse as patient advocate requires the nurse to be especially vigilant in terms of patient safety. Although this is expected of perioperative nurses, the ability to remain vigilant is difficult even in the best of circumstances.8 Typically, patients are interviewed, transported, and transferred many times throughout the process. They come into contact with many medical personnel who perform various technical procedures on them before and during their operative procedure. These multiple points of contact provide numerous opportunities for distractions, interruptions, errors, and misunderstandings of all kinds. Thus, a basic understanding of these factors affecting people can provide insight into error prevention strategies.

Human factors and active failures

The science of understanding human abilities and the effects of outside influences is termed human factors science. This involves all aspects of the way people relate to the organization where they work, with the aim of improving operational performance and safety. Today, health care organizations have become high-reliability organizations in that even though they make mistakes, they also have come to realize that people are humans and that the organization must be constantly preoccupied with the potential for error to occur and prepare in advance. In an ideal world the health care organization as a system has certain defenses or checks and balances that prevent error. However in reality these defenses are like walls of Swiss cheese, and when the holes in the cheese (active and latent failures) line up, mistakes are likely to happen.9 Distractions, interruptions, and miscommunications are some of the things that can get through the holes.10

Active failures are unsafe actions that originate from simply being human. There are limits that can be placed on human cognitive functions and the degree of stimulus that can be tolerated before processing breakdowns occur. Overstimulation in the form of interruptions to any degree can affect human accuracy, attention span, knowledge retrieval, focus and concentration, and the connection that must be made for precise motor skills to take place.9

There are two types of active failures that affect performance: (1) slips and lapses, and (2) mistakes. Slips and lapses result from a deviation from the plan, whereas mistakes result from the wrong plan.9 A slip occurs when the intended observable action is replaced by another action. Slips occur when a planned action fails, and when actions are governed by automatic and familiar patterns.10 For example, preparing the patient for surgery is typically governed by automatic influences. If the nurse (on the way to interviewing the patient) was interrupted by a request to also pick up and administer a medication, the nurse must disengage the internal “auto-pilot” to accomplish the goal. A slip would occur if the nurse inadvertently began the interview without the medication. Another example of a slip would be if the nurse did not show up for the extra shift after agreeing to work an extra day.

A lapse is when a memory cannot be recalled. This happens when a person forgets something they once knew such as facts about a medication. A mistake occurs when an incorrect planned action fails to achieve the intended goal, because the action choice was incorrect. Mistakes are further divided into knowledge-based, rule-based, and skill-based.10 Different levels of thinking are used by people in a variety of situations depending on their skill level, level of expertise, and experience in a particular setting. A basic understanding of each may help with handling different situations at different levels.

Knowledge Based Thinking

Knowledge-based behavior relies on familiarity with the situation, but is often learned by trial and error. In knowledge-based thinking, slips and lapses result from a deviation from the plan, whereas mistakes result from the wrong plan. Slips and lapses are also associated with functioning on “auto-pilot.” Knowledge-based thinking is novice thinking, and interruptions and distractions at this level can easily affect the especially because this person may not be equipped to handle unexpected changes. The information received may be unclear, or the person may lack knowledge or experience to handle the situation. For instance the ambiguous sounding alarm may be totally foreign to the person as well as the correct action required. Thus the person may try to silence a true alarm or take other inappropriate actions. Mistakes occur more often at the rule-based and knowledge-based levels following a poor decision.10

Rule Based Thinking

Rule-based behavior happens when the individual depends on rules to guide their actions. Rule-based thinkers rely on what was learned from instruction or from personal experience. Skills are learned, practiced, and eventually become automatic as the person progresses from novice to expert. In rule-based thinking, changes in situations are often anticipated because of past encounters, or as learned from instructors. Mistakes arise because of application of a bad rule or misapplication of a good rule. People tend to match the current pattern with one they have seen before and tend to think that the same solution will apply. For example if the nurse hears an alarm, he or she may make the decision that the alarm pattern matches a familiar sound, and ignore the true alarm, thinking it was false.10

Skill Based Thinking

With skill based thinking, the character and timing of the change may be known, but an alternate choice has not been fully planned. Slips result primarily from failures on the skill-based level. Though the chances for errors at this level are usually less, they have a greater magnitude of inaccuracy (strong-but-wrong).10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree