Skin Antisepsis: First Line of Defense Set Skin Preparation in Motion Before the Incision

Keywords

• Skin preparation agents • Manufacturer’s instructions • Surgical-site infection • Antiseptic agents

In 1992 the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) revised its definition of wound infection, creating the definition surgical-site infection (SSI). SSIs are infections that occur at any site along the surgical tract.1

Prevention of SSIs continues to be one of the greatest health care challenges in the world today. It is estimated that, in the United States alone, there are some 27 million annual surgical procedures resulting in 500,000 surgical-site infections.2 These infections have proved to be a major cause of patient injury and mortality, as well as adding to ever-increasing health care costs. Overall, SSIs are associated with $7 billion to $10 billion annually. In health care expenditures in the United States:

The patient’s own indigenous flora is the most common form of pathogen transmission leading to an SSI.4 Therefore, once the surgical incision has been made, the patient’s skin is no longer intact and is at risk for an infection to occur. Therefore, preparing the patients skin before the incision is made can potentially the patient from developing a SSI. The CDC defines surgical skin preparation as a “procedure for cleansing the skin with an antiseptic before the surgical procedure.”1 In the CDC Surgical-Site Infection Guidelines (1999), requiring patients to shower or bathe with an antiseptic agent on at least the night before the operative day is listed as a category IB recommendation (Box 1).1 It is strongly recommended that all surgical patients receive preoperative skin cleansing before their procedure, regardless of surgery type.

Box 1 CDC Recommended Guidelines rationale

Adapted from Appendix J. CDC Recommendation for the prevention of surgical site infections. 1999 Adapted from Mangram, HICPAC and CDC. Available at: http://www.cec.gov/ncidod/hip/SSI/SSI_guideline.htm.

According to the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN)

US Food and Drug Administration regulations of antiseptics

In the United States, drugs, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Thus antiseptics are under the jurisdiction of, and have parameters clearly defined by, the FDA. The health care facility should use FDA-approved agents that have immediate, cumulative, and persistent antimicrobial action6:

When evaluating antiseptic agents, the following FDA standards should be taken into consideration. The agents should substantially reduce transient microorganisms; possess a broad spectrum of antimicrobial properties; be fast acting; have persistent, cumulative activity; and be nonirritating to the skin.5

Most frequently used skin preparation agents

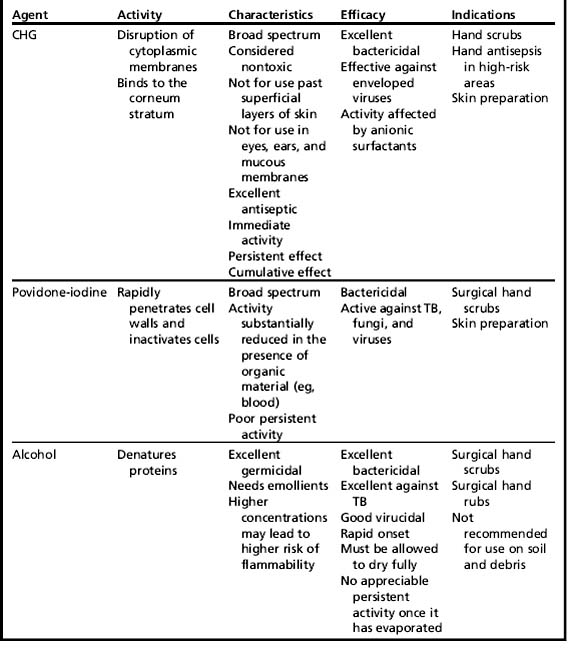

But when it comes to surgical skin preparation, plastic surgery is no different from other service lines. Patients must be protected from developing SSI’s. The 1999 CDC SSI guidelines require the “use of an appropriate agent for skin preparation.”1 These guidelines discuss several skin preparation agents that are in use today. Currently, the 2 most common skin preparation agents used in plastic/reconstructive surgery are chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG), (with or without alcohol), and povidone-iodine (with or without alcohol) (Table 1).7

According to the CDC, some comparisons of the 2 antiseptics when used as preoperative hand scrubs suggest that chlorhexidine gluconate achieved greater reductions in skin microflora than did povidone-iodine and also had greater residual activity after a single application.1 When reviewing literature of skin preparation agents, more and more researchers/practitioners are concluding that CHG is superior to other products related to skin disinfection. In a study by Darouiche and colleagues,8 preoperative cleansing of the patient’s skin with chlorhexidine-alcohol is superior to cleansing with povidone-iodine for preventing SSI after clean contaminated surgery. In a separate study by Fletcher and colleagues,9chlorhexidine gluconate was found to be superior to povidone-iodine for preoperative antisepsis for both the patient and surgeon.

In an article by Prasad and colleagues,10 the use of alcohol-based products for hand hygiene and skin antisepsis could initiate even greater concerns regarding the hazards of operating room fires. In the case study reviewed in the article by Prasad and colleagues,10 the patient was scheduled for a tracheostomy.

Types of skin preparation

Although the types of surgery frequently seen are related to the term plastic surgery, advances in the development of miniaturized instruments, new materials for artificial limbs and body parts, and improved surgical techniques have expanded the range of plastic surgery operations that can be performed. Three types of surgery share some common techniques and approaches, even though they have somewhat different emphases.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree