Should one use an open or closed rhinoplasty approach? How appropriate is the endonasal approach in modern-day rhinoplasty? Should the tip lobule be divided or preserved? Are alloplastic implants inferior to autologous implants? Does release and reduction of the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal dorsal septum always require spreader graft placement to prevent mid one-third nasal pinching in reduction rhinoplasty? Over past 5 years, how have rhinoplasty techniques and approaches evolved?

Minas Constantinides, Peter Adamson, Alyn Kim, and Steven Pearlman address questions for discussion and debate:

- 1.

Should one use an open or closed rhinoplasty approach?

- 2.

How appropriate is the endonasal approach in modern-day rhinoplasty?

- 3.

Should the tip lobule be divided or preserved?

- 4.

Are alloplastic implants inferior to autologous implants?

- 5.

- 6.

Constantinides: introduction

Theory without practice is like a one-winged bird that is incapable of flight.

Science is the father of knowledge, but opinion breeds ignorance.

I am an open rhinoplasty surgeon. Since entering practice in 1994, I have performed over 2000 primary and revision open rhinoplasties. As Director of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery in the Department of Otolaryngology at New York University School of Medicine, I teach and operate at NYU Langone Medical Center, Bellevue Hospital Center, and the Manhattan Veterans Administration Hospital. From my first day in practice I have been a rhinoplasty teacher. I have taught 19 years’ worth of residents open rhinoplasty, and many have gone on to perform rhinoplasty in their practices. In 2000 I started a fellowship in Facial Plastic Surgery. I included Drs Norman Pastorek and Philip Miller in order to give my fellows a wide array of exposure to various approaches in rhinoplasty (in addition to all other aspects of facial plastic surgery). I recognize the importance of seeing a variety of surgeons handle a variety of problems in unique ways. I could think of no one better to teach closed rhinoplasty that Dr Pastorek, probably the best closed surgeon in the world today.

The controversies discussed in this Clinics issue are well chosen to reflect how my own philosophy has changed over my years in practice. In my answers, I hope to paint a picture of how I decide to do what I do in rhinoplasty today, why I have changed what I do over the years and how even now I am looking for better ways to improve what I do. Dr Eugene Tardy has said, “the rhinoplasty student never graduates.” This complex and beautiful operation is at once rewarding and humbling. I am blessed that my practice is a rhinoplasty practice on such a large and demanding stage.

Should one use an open or closed rhinoplasty approach?

Adamson and Kim

Open septorhinoplasty (OSR) was introduced 40 years ago in North America and has since gained wide acceptance as a good approach, if not the preferred approach, for rhinoplasty. In a survey by Dayan and Kanodia of fellowship graduates of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery between 1997 and 2007, they found that the vast majority, 87.9%, performed open rhinoplasty as their primary approach. The open approach to rhinoplasty has been controversial since its inception, but this statistic indicates increasingly wide acceptance of this approach. In the past, open rhinoplasty was supported for difficult or revision cases only. Proponents of closed rhinoplasty initially criticized the open technique, citing potential problems such as unnecessary scarring, reduction of tip support, extended operative time, and excessive postoperative tip swelling. The issue of columellar scarring was addressed by Vuyk and Olde Kalter in a meta-analysis of 7 articles encompassing 986 patients who underwent open septorhinoplasty. Only 3 had columellar flap necrosis that led to scarring. Another argument against OSR was that the open scar was longer when, in fact, it, and the marginal incision, are shorter than the scars of a cartilage delivery technique and do not affect the internal valve, an area of potential functional compromise in closed approaches. Other potential arguments against the open approach are purportedly longer lasting supratip swelling and longer operative times. Toriumi and colleagues used cadaver studies to demonstrate that the main vasculature of the nose runs aloft the musculoaponeurotic layer, or in it and parallel to the alar margin, as opposed to vertically in the columella. Thus, it is dissection above the musculoaponeurotic layer that disrupts and perhaps prolongs postoperative tip edema, not the transcolumellar incision of OSR. Indeed, operative times may be longer with OSR because more time may be taken to deal with the asymmetries that are uncovered.

The open approach clearly offers better exposure to a small surgical field, thereby affording the opportunity to better diagnose the deformity through inspection, to better execute certain maneuvers, and to teach and to learn the operation with greater ease. Indications have expanded with widespread increasing levels of comfort and familiarity with the technique. In my experience, open rhinoplasty is the technique of choice for all cases unless a comparable improvement for a definable deformity can be obtained with the closed approach. The open approach offers clear diagnostic and therapeutic advantages for many challenging functional and cosmetic nasal deformities, primarily resulting from the broad undistorted exposure it affords and the improved opportunity for bimanual correction. This is especially true with respect to the premaxillary spine, caudal septum, dorsal and superior septum, lobule, and superior dorsum. The open approach offers an unparalleled appreciation of the underlying anatomy resulting in the external deformity. Sutures can be placed, grafts trimmed exactly, and asymmetries corrected without distortion of surrounding tissues. Scar tissue and redundant subcutaneous tissue are more easily excised. The valve region can be well protected, and the absence of incisions in the intercartilaginous region diminishes subsequent obstructive phenomena by precluding scar formation and disruption of one of the tip support mechanisms. It may also be that revision rates for primary OSR are less than those for closed rhinoplasty.

OSR provides an opportunity for greater surgical exposure for the operating surgeon and the assistants, and thereby provides an excellent teaching tool. As this approach is used in didactic teaching sessions, more surgeons in training are exposed to the approach and may be more apt to continue with this approach in their later practices. In general, surgeons with the greatest experience (more than 100 rhinoplasties per year) tend to use the closed approach more often, but, nonetheless, even they still perform a notable amount of OSR. There is still some trend to increasing use of the OSR approach: the only group using it slightly less are those in practice 16 to 25 years—older surgeons who were less exposed to the OSR approach in their training and continue to practice in the manner in which they were trained. Younger surgeons perform open rhinoplasty more frequently compared with older surgeons for all indications. The movement toward open rhinoplasty seems to be plateauing with possibly a slight upward trend in its use. Except for “simple” cases, OSR may be indicated for rhinoplasty by a large proportion of surgeons, especially for rhinoplasties that are “difficult” or revisions or those requiring grafting. When all is said and done, each surgeon will assess the patient’s deformity and their own ability to correct it, and will utilize the approach that works best for them. There will always be room for differing opinions and different approaches.

Constantinides

Note: Constantinides here discusses open versus closed approach jointly with the next discussion of endonasal approach.

When discussing open and closed approaches, the terms themselves engender controversy. “Open” is also called “external” while “closed” is called “endonasal.” Should one set of terms be abandoned for another? There are good arguments on both sides. In favor of keeping “open” and “closed” are the arguments that:

- •

“Closed” correctly characterizes the approach as obscured, with inferior visualization and poor ability to exactly manipulate cartilages in their native position.

- •

“External” correctly characterizes the trivial columellar incision as being of consequence. It is not.

- •

It is simpler for a patient to say and to remember “open” and “closed.”

In favor of using “external” and “endonasal”:

- •

“Closed” was called “closed” only when the “open” approach was introduced.

- •

“Closed” implies without incisions, as in “closed reduction of a nasal fracture.”

- •

“Endonasal” correctly refers to an approach with incisions only inside the nose.

Historical perspective is important. The open approach was used in Germany by Johann Friedrich Diffenbach who described a dorsal midline vertical incision in his “Die Operative Chirurgie” in 1845. Jacques Joseph’s first case in 1898 used the same approach, but he later switched to an endonasal approach to avoid the scar. He thought he was first to perform an endonasal rhinoplasty, but had been beaten by two New York surgeons. John Orlando Roe reported the first endonasal rhinoplasty in 1887 and Robert F. Weir reported his first in 1892 (although he claimed he had performed it in 1885 in order to beat Roe).

What does a Google search reveal on “Open versus Closed Rhinoplasty”? The #1 position is held by Dr Steven M. Denenberg, who lists a number of conditions that must exist for him to use the closed approach. He summarizes by saying: “I use the closed technique only about 5% of the time.” Other positions by other surgeons (some well-known, others not) essentially summarize the arguments that I have listed in often colorful (and sometimes misleading) language that captures each surgeon’s individual sentiments on the subject. On the Web, the “open versus closed” argument is used as a publicity tool to scare patients away from one approach or the other, depending upon each surgeon’s bias. Is there any wonder there is so much disinformation and confusion on this topic in the public’s eye?

Since this issue of Clinics is to capture each expert’s description of his particular approach, I will limit myself to a description of my open approach. I only use the closed approach in very minor revisions and never in primary rhinoplasty. Unlike Dr Denenberg, I have never found a primary rhinoplasty in which I do not want to fully visualize the entire nose. Even for relatively simple changes, the open approach allows me the possibility of hitting a home run. With the closed approach, I am worried that I will not have accounted for some unnoticed issue (cephalic excision releasing the lateral crus to become convex postop; minor dorsal reduction causing asymmetric upper lateral cartilage (ULC) weakness and postop irregularity) that could lead to a postoperative problem.

The incisions and the columellar scar

I use the same incision Goodman used when he introduced open rhinoplasty in Canada in 1979, the inverted “V” incision. The alternate incision, the stair-step incision, I long thought was equivalent until I started having to revise it. There are several real problems with the stair-step. One is that the lateral limbs of the incision should be at the narrowest part of the columella. This is so that the incision is placed where the medial crura are closest to the skin. The underlying cartilage provides support against contraction, insuring the best possible resultant scar. Indeed, in columellas with thicker skin, I make sure that I reinforce the underlying cartilaginous support to insure a strong platform that resists contraction. The stair-step incision’s lateral limbs are not ideally placed.

With the stair-step incision one limb is higher on one side of the columella than the other. If scar revision is required, excising the incision can leave one side of the resultant scar too close to the top of the columella, creating the potential for notching and nostril asymmetry. The inverted “V” incision forces the resultant limbs lower on the columella, so any subsequent scar revision is simpler and the chance for asymmetry is less ( Fig. 1 ).

If performing scar revision, the resulting closing tension may be improved by extending the marginal incisions inferiorly toward the sill. The lower portion of the columella then may be dissected as an advancement flap, providing ample release and decreasing the closing tension. A single buried 5-0 Monocryl suture in the midline further reduces the chance of scar widening during the contraction phase of healing. Simple 6-0 nylon interrupted sutures placed to evert the skin edges create a nearly invisible scar.

Another variable when planning the open incision is the lateral extent of the marginal incision. In primary rhinoplasties, my marginal incisions now end where the caudal edges of the lateral crura diverge cephalically away from the rim. Extending the marginal incision more laterally does little to enhance exposure; the lateral crura may still be dissected in their entirety without a longer marginal incision. Limiting the length of the marginal incision has theoretic and practical benefits. Theoretically, there is less disruption of the lateral lymphatics and vascular drainage from the tip. This may lead to less edema postoperatively and less chance of prolonged thickening of the soft tissue envelope. Practically, the shorter marginal incision allows more stability when placing rim grafts and batten grafts into pockets in this area.

Point of view

The main practical difference between an open and a closed exposure is the point of view of the surgeon. From a closed exposure, the surgeon’s point of view is from lateral to medial. When dissecting and then viewing the dissected structures, the surgeon looks from lateral to medial, whether looking through a marginal or an intercartilaginous incision. From this point of view, it is impossible to directly judge bilateral symmetry simultaneously. Instead, the closed surgeon must judge symmetry by viewing and palpating the nose externally through an already dissected soft tissue envelope. This may be why a skilled closed surgeon has such difficulty with the open approach. He is used to judging symmetry while looking from the outside. His eye is not used to judging symmetry by directly observing the dissected structures, especially when the transcolumellar incision has freed the skin envelope in a way he is not used to seeing.

The open approach affords a completely different point of view. Instead of dissecting and viewing from lateral to medial, the surgeon begins by dissecting symmetrically and bilaterally. The entire operation develops from a midline perspective. This makes the open approach exceptionally suited for creating symmetry from the midline. The direct exposure of nasal structures as they diverge from the midline allows the surgeon an unparalleled view for creating a symmetric result. This is why an open surgeon has such difficulty with the closed approach. He is used to seeing the nasal structures from the top down, symmetrically and bilaterally. He is not used to judging symmetry by observing it from lateral to medial, and is not used to trusting what he sees when looking through a dissected soft tissue envelope. Most of the “rules” that surgeons have created about when to use the open or the closed approach have to do with this difference in surgical point of view.

I am an open rhinoplasty surgeon. I have gotten accustomed to creating symmetric, stable results using a midline point of view. I admire my closed rhinoplasty colleagues who create exceptional results from another point of view, but I do not covet their approach. I know the open approach in my hands gives my patients the best chance for an exceptional result with the least chance of any asymmetry or irregularity. The columellar scar is inconsequential; no blog entry will convince me otherwise.

Pearlman

I’m honored to have been asked to participate in this exciting format for this issue of Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics . I feel that it’s important to preface my remarks by clarifying the topic. To begin, the correct terms are more appropriately labeled: “external” and “endonasal” approaches to rhinoplasty. Additionally the use of the conjunction “versus” implies a competition, or adversarial dispute among surgeons who choose, and surgeons who choose not to use a tiny incision across the columella. I will address this alleged controversy more specifically in the next section. Most important in nasal surgery is not which approach is used, but the understanding of nasal anatomy, the repertoire of surgical maneuvers, and the consequence of each of those surgical maneuvers. Actually seeing the nasal structures by using an external approach and peeling back the skin does not automatically impart an understanding of nasal anatomy and surgical technique; it only provides a better view.

In what many consider a landmark textbook, Open Structure Rhinoplasty , Johnson and Toriumi built on the approach first described by Rethi, revived by Padovan, and brought to North America by Goodman. The addition of the principle of “structure” is the key and the true genius of that simple phrase and book title. Structure must be maintained or restored in both external and endonasal rhinoplasty.

Emphasizing the importance of structure and its necessity for successful rhinoplasty follows the architectural dictum: “form follows function.” Although this phrase was first coined by the mid-nineteenth century sculptor Horatio Greenough, it has more commonly been applied to the modernist architecture movement of Louis Sullivan and his disciple Frank Lloyd Wright. Their German counterpart, the Bauhaus, espoused similar principles. When analyzing the appearance of a nose and proposing surgery, especially for revision rhinoplasty, I often bring up the concept of “form follows function.” What doesn’t look good in an overdone nose doesn’t work well either. The reverse is true as well, what doesn’t work well also doesn’t look natural.

The surgical techniques we employ to make noses look better should also improve nasal function. Occasionally patients actually state that they don’t care about their airway in deference to an improved appearance, which is heard more often during a revision rhinoplasty consultation. It should be pointed out that, unless they are seeking a tiny pinched nose, as was fashionable in the 1960s, both improved form and function can, and should, be addressed. What we are creating or restoring is a more attractive conduit that functions as a Starling resistor being acted on by Bernoulli forces. The nasal walls need the size and strength to resist the negative pressure due to air flow in the upper airway.

Maintaining or restoring nasal structure through the use of spreader grafts to support the middle vault was first proposed by Sheen over a decade before Johnson, yet Sheen practiced exclusively endonasal surgery. Personally, I am now using spreader grafts in well over 90% of both primary and revision rhinoplasties through either the external or endonasal approach (see question below: Are alloplastic implants inferior to autologous implants ?).

Structure is important for the external nasal vault as well. Over the past few decades we have been taught to leave increasingly more lateral crural height. Yet we still want more refined nasal tips. Tip narrowing or sculpting sutures can be used for additional refinement. Now that the importance of middle vault structure and support has been well established, authors have become increasingly aware of the complex contributions of the lateral crura to external valve form and function.

Despite many advances in rhinoplasty over the past few decades the rate of revision rhinoplasty still hasn’t changed. Recently, I have found that the majority of revision rhinoplasties I perform are on external rhinoplasties, unless the rhinoplasty was performed over 15 years ago. This is not a condemnation of that approach, but more likely due to the overwhelming majority of current practitioners using that approach. There are a number of questions that remain on the topic of revision rates. Is it that there are more surgeons attempting rhinoplasty? Are the patients becoming more sophisticated and exacting, or are the ideas of what constitutes an acceptable result in the eyes of both surgeons and patients more stringent than 2 decades ago? Does the open approach make rhinoplasty seem easier and more likely for the uninitiated surgeon to attempt? I would delve further, but this subject is more appropriate for another discussion.

I have strayed from the assigned question of open versus closed rhinoplasty. That is because it’s less a controversy and more a choice. I know a number of very skilled surgeons who get superb results from both approaches.

Should one use an open or closed rhinoplasty approach?

Adamson and Kim

Open septorhinoplasty (OSR) was introduced 40 years ago in North America and has since gained wide acceptance as a good approach, if not the preferred approach, for rhinoplasty. In a survey by Dayan and Kanodia of fellowship graduates of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery between 1997 and 2007, they found that the vast majority, 87.9%, performed open rhinoplasty as their primary approach. The open approach to rhinoplasty has been controversial since its inception, but this statistic indicates increasingly wide acceptance of this approach. In the past, open rhinoplasty was supported for difficult or revision cases only. Proponents of closed rhinoplasty initially criticized the open technique, citing potential problems such as unnecessary scarring, reduction of tip support, extended operative time, and excessive postoperative tip swelling. The issue of columellar scarring was addressed by Vuyk and Olde Kalter in a meta-analysis of 7 articles encompassing 986 patients who underwent open septorhinoplasty. Only 3 had columellar flap necrosis that led to scarring. Another argument against OSR was that the open scar was longer when, in fact, it, and the marginal incision, are shorter than the scars of a cartilage delivery technique and do not affect the internal valve, an area of potential functional compromise in closed approaches. Other potential arguments against the open approach are purportedly longer lasting supratip swelling and longer operative times. Toriumi and colleagues used cadaver studies to demonstrate that the main vasculature of the nose runs aloft the musculoaponeurotic layer, or in it and parallel to the alar margin, as opposed to vertically in the columella. Thus, it is dissection above the musculoaponeurotic layer that disrupts and perhaps prolongs postoperative tip edema, not the transcolumellar incision of OSR. Indeed, operative times may be longer with OSR because more time may be taken to deal with the asymmetries that are uncovered.

The open approach clearly offers better exposure to a small surgical field, thereby affording the opportunity to better diagnose the deformity through inspection, to better execute certain maneuvers, and to teach and to learn the operation with greater ease. Indications have expanded with widespread increasing levels of comfort and familiarity with the technique. In my experience, open rhinoplasty is the technique of choice for all cases unless a comparable improvement for a definable deformity can be obtained with the closed approach. The open approach offers clear diagnostic and therapeutic advantages for many challenging functional and cosmetic nasal deformities, primarily resulting from the broad undistorted exposure it affords and the improved opportunity for bimanual correction. This is especially true with respect to the premaxillary spine, caudal septum, dorsal and superior septum, lobule, and superior dorsum. The open approach offers an unparalleled appreciation of the underlying anatomy resulting in the external deformity. Sutures can be placed, grafts trimmed exactly, and asymmetries corrected without distortion of surrounding tissues. Scar tissue and redundant subcutaneous tissue are more easily excised. The valve region can be well protected, and the absence of incisions in the intercartilaginous region diminishes subsequent obstructive phenomena by precluding scar formation and disruption of one of the tip support mechanisms. It may also be that revision rates for primary OSR are less than those for closed rhinoplasty.

OSR provides an opportunity for greater surgical exposure for the operating surgeon and the assistants, and thereby provides an excellent teaching tool. As this approach is used in didactic teaching sessions, more surgeons in training are exposed to the approach and may be more apt to continue with this approach in their later practices. In general, surgeons with the greatest experience (more than 100 rhinoplasties per year) tend to use the closed approach more often, but, nonetheless, even they still perform a notable amount of OSR. There is still some trend to increasing use of the OSR approach: the only group using it slightly less are those in practice 16 to 25 years—older surgeons who were less exposed to the OSR approach in their training and continue to practice in the manner in which they were trained. Younger surgeons perform open rhinoplasty more frequently compared with older surgeons for all indications. The movement toward open rhinoplasty seems to be plateauing with possibly a slight upward trend in its use. Except for “simple” cases, OSR may be indicated for rhinoplasty by a large proportion of surgeons, especially for rhinoplasties that are “difficult” or revisions or those requiring grafting. When all is said and done, each surgeon will assess the patient’s deformity and their own ability to correct it, and will utilize the approach that works best for them. There will always be room for differing opinions and different approaches.

Constantinides

Note: Constantinides here discusses open versus closed approach jointly with the next discussion of endonasal approach.

When discussing open and closed approaches, the terms themselves engender controversy. “Open” is also called “external” while “closed” is called “endonasal.” Should one set of terms be abandoned for another? There are good arguments on both sides. In favor of keeping “open” and “closed” are the arguments that:

- •

“Closed” correctly characterizes the approach as obscured, with inferior visualization and poor ability to exactly manipulate cartilages in their native position.

- •

“External” correctly characterizes the trivial columellar incision as being of consequence. It is not.

- •

It is simpler for a patient to say and to remember “open” and “closed.”

In favor of using “external” and “endonasal”:

- •

“Closed” was called “closed” only when the “open” approach was introduced.

- •

“Closed” implies without incisions, as in “closed reduction of a nasal fracture.”

- •

“Endonasal” correctly refers to an approach with incisions only inside the nose.

Historical perspective is important. The open approach was used in Germany by Johann Friedrich Diffenbach who described a dorsal midline vertical incision in his “Die Operative Chirurgie” in 1845. Jacques Joseph’s first case in 1898 used the same approach, but he later switched to an endonasal approach to avoid the scar. He thought he was first to perform an endonasal rhinoplasty, but had been beaten by two New York surgeons. John Orlando Roe reported the first endonasal rhinoplasty in 1887 and Robert F. Weir reported his first in 1892 (although he claimed he had performed it in 1885 in order to beat Roe).

What does a Google search reveal on “Open versus Closed Rhinoplasty”? The #1 position is held by Dr Steven M. Denenberg, who lists a number of conditions that must exist for him to use the closed approach. He summarizes by saying: “I use the closed technique only about 5% of the time.” Other positions by other surgeons (some well-known, others not) essentially summarize the arguments that I have listed in often colorful (and sometimes misleading) language that captures each surgeon’s individual sentiments on the subject. On the Web, the “open versus closed” argument is used as a publicity tool to scare patients away from one approach or the other, depending upon each surgeon’s bias. Is there any wonder there is so much disinformation and confusion on this topic in the public’s eye?

Since this issue of Clinics is to capture each expert’s description of his particular approach, I will limit myself to a description of my open approach. I only use the closed approach in very minor revisions and never in primary rhinoplasty. Unlike Dr Denenberg, I have never found a primary rhinoplasty in which I do not want to fully visualize the entire nose. Even for relatively simple changes, the open approach allows me the possibility of hitting a home run. With the closed approach, I am worried that I will not have accounted for some unnoticed issue (cephalic excision releasing the lateral crus to become convex postop; minor dorsal reduction causing asymmetric upper lateral cartilage (ULC) weakness and postop irregularity) that could lead to a postoperative problem.

The incisions and the columellar scar

I use the same incision Goodman used when he introduced open rhinoplasty in Canada in 1979, the inverted “V” incision. The alternate incision, the stair-step incision, I long thought was equivalent until I started having to revise it. There are several real problems with the stair-step. One is that the lateral limbs of the incision should be at the narrowest part of the columella. This is so that the incision is placed where the medial crura are closest to the skin. The underlying cartilage provides support against contraction, insuring the best possible resultant scar. Indeed, in columellas with thicker skin, I make sure that I reinforce the underlying cartilaginous support to insure a strong platform that resists contraction. The stair-step incision’s lateral limbs are not ideally placed.

With the stair-step incision one limb is higher on one side of the columella than the other. If scar revision is required, excising the incision can leave one side of the resultant scar too close to the top of the columella, creating the potential for notching and nostril asymmetry. The inverted “V” incision forces the resultant limbs lower on the columella, so any subsequent scar revision is simpler and the chance for asymmetry is less ( Fig. 1 ).

If performing scar revision, the resulting closing tension may be improved by extending the marginal incisions inferiorly toward the sill. The lower portion of the columella then may be dissected as an advancement flap, providing ample release and decreasing the closing tension. A single buried 5-0 Monocryl suture in the midline further reduces the chance of scar widening during the contraction phase of healing. Simple 6-0 nylon interrupted sutures placed to evert the skin edges create a nearly invisible scar.

Another variable when planning the open incision is the lateral extent of the marginal incision. In primary rhinoplasties, my marginal incisions now end where the caudal edges of the lateral crura diverge cephalically away from the rim. Extending the marginal incision more laterally does little to enhance exposure; the lateral crura may still be dissected in their entirety without a longer marginal incision. Limiting the length of the marginal incision has theoretic and practical benefits. Theoretically, there is less disruption of the lateral lymphatics and vascular drainage from the tip. This may lead to less edema postoperatively and less chance of prolonged thickening of the soft tissue envelope. Practically, the shorter marginal incision allows more stability when placing rim grafts and batten grafts into pockets in this area.

Point of view

The main practical difference between an open and a closed exposure is the point of view of the surgeon. From a closed exposure, the surgeon’s point of view is from lateral to medial. When dissecting and then viewing the dissected structures, the surgeon looks from lateral to medial, whether looking through a marginal or an intercartilaginous incision. From this point of view, it is impossible to directly judge bilateral symmetry simultaneously. Instead, the closed surgeon must judge symmetry by viewing and palpating the nose externally through an already dissected soft tissue envelope. This may be why a skilled closed surgeon has such difficulty with the open approach. He is used to judging symmetry while looking from the outside. His eye is not used to judging symmetry by directly observing the dissected structures, especially when the transcolumellar incision has freed the skin envelope in a way he is not used to seeing.

The open approach affords a completely different point of view. Instead of dissecting and viewing from lateral to medial, the surgeon begins by dissecting symmetrically and bilaterally. The entire operation develops from a midline perspective. This makes the open approach exceptionally suited for creating symmetry from the midline. The direct exposure of nasal structures as they diverge from the midline allows the surgeon an unparalleled view for creating a symmetric result. This is why an open surgeon has such difficulty with the closed approach. He is used to seeing the nasal structures from the top down, symmetrically and bilaterally. He is not used to judging symmetry by observing it from lateral to medial, and is not used to trusting what he sees when looking through a dissected soft tissue envelope. Most of the “rules” that surgeons have created about when to use the open or the closed approach have to do with this difference in surgical point of view.

I am an open rhinoplasty surgeon. I have gotten accustomed to creating symmetric, stable results using a midline point of view. I admire my closed rhinoplasty colleagues who create exceptional results from another point of view, but I do not covet their approach. I know the open approach in my hands gives my patients the best chance for an exceptional result with the least chance of any asymmetry or irregularity. The columellar scar is inconsequential; no blog entry will convince me otherwise.

Pearlman

I’m honored to have been asked to participate in this exciting format for this issue of Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics . I feel that it’s important to preface my remarks by clarifying the topic. To begin, the correct terms are more appropriately labeled: “external” and “endonasal” approaches to rhinoplasty. Additionally the use of the conjunction “versus” implies a competition, or adversarial dispute among surgeons who choose, and surgeons who choose not to use a tiny incision across the columella. I will address this alleged controversy more specifically in the next section. Most important in nasal surgery is not which approach is used, but the understanding of nasal anatomy, the repertoire of surgical maneuvers, and the consequence of each of those surgical maneuvers. Actually seeing the nasal structures by using an external approach and peeling back the skin does not automatically impart an understanding of nasal anatomy and surgical technique; it only provides a better view.

In what many consider a landmark textbook, Open Structure Rhinoplasty , Johnson and Toriumi built on the approach first described by Rethi, revived by Padovan, and brought to North America by Goodman. The addition of the principle of “structure” is the key and the true genius of that simple phrase and book title. Structure must be maintained or restored in both external and endonasal rhinoplasty.

Emphasizing the importance of structure and its necessity for successful rhinoplasty follows the architectural dictum: “form follows function.” Although this phrase was first coined by the mid-nineteenth century sculptor Horatio Greenough, it has more commonly been applied to the modernist architecture movement of Louis Sullivan and his disciple Frank Lloyd Wright. Their German counterpart, the Bauhaus, espoused similar principles. When analyzing the appearance of a nose and proposing surgery, especially for revision rhinoplasty, I often bring up the concept of “form follows function.” What doesn’t look good in an overdone nose doesn’t work well either. The reverse is true as well, what doesn’t work well also doesn’t look natural.

The surgical techniques we employ to make noses look better should also improve nasal function. Occasionally patients actually state that they don’t care about their airway in deference to an improved appearance, which is heard more often during a revision rhinoplasty consultation. It should be pointed out that, unless they are seeking a tiny pinched nose, as was fashionable in the 1960s, both improved form and function can, and should, be addressed. What we are creating or restoring is a more attractive conduit that functions as a Starling resistor being acted on by Bernoulli forces. The nasal walls need the size and strength to resist the negative pressure due to air flow in the upper airway.

Maintaining or restoring nasal structure through the use of spreader grafts to support the middle vault was first proposed by Sheen over a decade before Johnson, yet Sheen practiced exclusively endonasal surgery. Personally, I am now using spreader grafts in well over 90% of both primary and revision rhinoplasties through either the external or endonasal approach (see question below: Are alloplastic implants inferior to autologous implants ?).

Structure is important for the external nasal vault as well. Over the past few decades we have been taught to leave increasingly more lateral crural height. Yet we still want more refined nasal tips. Tip narrowing or sculpting sutures can be used for additional refinement. Now that the importance of middle vault structure and support has been well established, authors have become increasingly aware of the complex contributions of the lateral crura to external valve form and function.

Despite many advances in rhinoplasty over the past few decades the rate of revision rhinoplasty still hasn’t changed. Recently, I have found that the majority of revision rhinoplasties I perform are on external rhinoplasties, unless the rhinoplasty was performed over 15 years ago. This is not a condemnation of that approach, but more likely due to the overwhelming majority of current practitioners using that approach. There are a number of questions that remain on the topic of revision rates. Is it that there are more surgeons attempting rhinoplasty? Are the patients becoming more sophisticated and exacting, or are the ideas of what constitutes an acceptable result in the eyes of both surgeons and patients more stringent than 2 decades ago? Does the open approach make rhinoplasty seem easier and more likely for the uninitiated surgeon to attempt? I would delve further, but this subject is more appropriate for another discussion.

I have strayed from the assigned question of open versus closed rhinoplasty. That is because it’s less a controversy and more a choice. I know a number of very skilled surgeons who get superb results from both approaches.

How appropriate is the endonasal approach in modern-day rhinoplasty?

Adamson and Kim

OSR has been found useful for most indications except for the “simple” tip or dorsum. The closed, or endonasal approaches continue to have their proponents, for very good reasons, and appear to be especially useful for the “simple” tip and dorsum. The most experienced surgeons may favor the closed approaches, but even they have initiated notable use of OSR. Perhaps the consensus opinion is best summed up by recognizing the challenging operation that rhinoplasty is and the unique training and experience that each rhinoplasty surgeon has. I recommend that each surgeon initially consider the open approach for a given case, unless the surgeon believes he or she can make the diagnosis and correct the deformities with a closed approach, in which case it can be used. I also recommend that rather than learning and less frequently applying a large number of approaches in one’s armamentarium, a surgeon use as small a number of approaches as necessary and use them more frequently to achieve good results within one’s experience. In this way, a surgeon increases his or her experience and becomes maximally adept at each.

Constantinides

Readers are directed to Constantinides’ responses to the previous question

Pearlman

The endonasal approach to rhinoplasty is absolutely appropriate in modern-day rhinoplasty if the surgeon is well trained in the procedure. Results from skilled surgeons are just as good as their counterparts who utilize the external approach exclusively.

Just stating this question actually counters the 2-decade-old contention about open versus closed rhinoplasty. I have heard it said that closed rhinoplasty is practiced with a closed mind and open rhinoplasty an open mind to a more modern technique. I feel the opposite may be true. It has been more my experience that surgeons who exclusively practice the open or external approach are more critical and less accepting of the closed, or endonasal approach; and those of us who still use the endonasal approach more often accept that there is an alternative.

Personally, I use the endonasal approach in 85% of primary rhinoplasties and the external approach in the majority of revision cases. With proper planning in primary rhinoplasty, the external approach is rarely necessary. My personal indications for external rhinoplasty are in Box 1 . However, in difficult cases, a transcolumellar incision can be added during endonasal rhinoplasty if closer inspection is required or difficulties arise that cannot be diagnosed or addressed by alar cartilage delivery.

- •

Extremely crooked nose, especially with complex septal curvature

- •

Lengthening a very short nose

- •

Significant deprojection and rotation of a very large nose

- •

Complex revision rhinoplasty

My personal indications for external rhinoplasty are: very crooked noses often require scoring with mattress sutures as well as spreader and other grafts to stent the septum. Use of polydioxanone (PDS) flexible foil has been a big help in getting very crooked noses straighter, particularly when there is curvature of the caudal-most septum. Rarely, extracorporeal septoplasty is used for complex septal deviation that requires an external approach.

To lengthen a short nose, all 3 limbs of the tip tripod require lengthening. Centrally, a caudal septal extension graft is placed with spreader grafts and/or PDS flexible foil. The lateral crura also need to be elevated from the underlying mucosa and thrust downward. I find these maneuvers are best achieved through an external approach.

I have reduced very large overprojected noses through the endonasal approach, but in 2 patients within recent memory, I have needed to go back to get further reduction. So, for very large, overprojected noses, I also generally start with an external technique.

In revision rhinoplasty, unless the revision is only for minor irregularities or reductions, an external approach affords a better view of the distorted anatomy without further disturbance or distortion when delivering the lower lateral cartilages during an endonasal approach. When one or more prior surgeries have been performed, sutures and grafts may have been placed, structures may have twisted, and scar tissue has likely formed. Even if I obtain prior surgical notes, they may not be entirely accurate and will not reflect postoperative scarring and warping. Through an external approach, I can see better how form and function are compromised. During revision rhinoplasty, I often use multiple grafts placed in both anatomic and unanatomic areas that are made easier by the external approach.

One might invoke the same reasoning for why an external approach should be used for primary rhinoplasty as well. However, comprehensive knowledge of nasal anatomy, thorough examination, and solid understanding of the consequences of surgical maneuvers allows equivalent results with endonasal rhinoplasty. I have heard it argued that the external approach is better for teaching residents. But if all a resident sees is the external approach, they will never learn endonasal rhinoplasty. If it’s about seeing, teaching, or understanding the anatomy better, then they should take one or more cadaver courses.

Quality rhinoplasty still takes years of study no matter what incision is used. It’s akin to the revolution of endoscopic sinus surgery in the late 1980s and early 1990s. I was fortunate enough to have been trained in endonasal sinus surgery. The key to successful surgery was thorough knowledge of sinus anatomy and surgical landmarks. When endoscopic surgery was first introduced, complications skyrocketed to the point that endoscopic sinus surgery was the most common reason for otolaryngologists to be sued for malpractice. Adding a telescope and getting a closer view of the sinuses did not automatically impart surgical knowledge. Individuals who might not otherwise have attempted advanced sinus surgery were emboldened by the false safety of a better view. Surgeons still need to take multiple courses with cadaver dissection and observe skilled teachers to become proficient at this procedure.

Minimally invasive surgery and minimizing incisions have become the mantra of many other surgical specialties. There isn’t one surgical specialty where you won’t hear about smaller scars with quality results in both the medical literature and lay media. Why not learn how to offer the same choices to your rhinoplasty patients? When discussing the difference between endonasal and external rhinoplasty with prospective patients, I review the indications for my incisions. If they have seen or read about other surgeons who offered a different approach, I discuss that the incision is tiny and rarely visible, and avoid any denigration of another technique. If an external approach is chosen by the surgeon and the transcolumellar scar becomes visible at all, it would be likely only to someone who is up under their nose and close enough to be “counting nose hairs,” However, it’s still comforting to patients to be offered the opportunity to have an equally successful rhinoplasty without any external incisions and zero chance of visible scar.

Should the tip lobule be divided or preserved?

Adamson and Kim

It is a rhinoplasty myth that if you divide the tip lobule you cannot preserve it. In fact, in many cases, division with reconstruction is much more preferable than preservation of a deformity. Therefore, we do not hesitate to use vertical lobule division (VLD) to correct tip abnormalities and irregularities, as it is a versatile and safe technique with predictable outcomes. We also distinguish between vertical arch division (VAD), which is a vertical division anywhere in the M-arch, and VLD, which is vertical division within the lobule or domal arch. VLD can be used to decrease projection; to narrow a wide or boxy tip; to correct knuckling, bossae, tip asymmetry, or a hanging columella; and to improve rotation. It was first described by Goldman in 1957 for increasing tip projection and rotation endonasally. It consisted of a vertical division of skin and cartilage lateral to the apex of the lobule and borrowing from the lower lateral cartilage to add length to the medial crus, or what is today known as the intermediate crus. Because the two anterior ends of the medial (intermediate) crura were sutured together, but were not resutured to the lateral crura, the division created instability and sometimes resulted in bossae, knuckling, asymmetries, and tip irregularities. Following this, cartilage excision techniques were introduced for vertical dome (lobule) division to correct deformities and/or shorten the lobular arch. Initially the cut cartilage ends were not secured to each other, but ultimately it was recognized that suturing the cut ends together increased stability and decreased longer term residual deformities. The next step in the development of VAD was incision only with overlapping and suturing the cartilage segments. This newer technique was used to decrease the length of the lobular arch to decrease projection and/or improve lobular arch symmetry, at the same time increasing stability and decreasing revision rates. In time, the versatility of this incision and overlap technique with suture stabilization has been applied to all regions of the medial, intermediate, and lateral crura. The current terminology is to call these overlay techniques, and they can be performed wherever desired in the M-arch. So it can be seen that dividing the lobule has many applications and advantages. However, it is imperative to appreciate that “vertical division” does not necessarily refer to the Goldman technique uniquely.

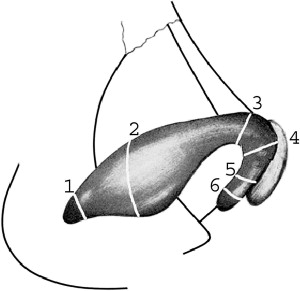

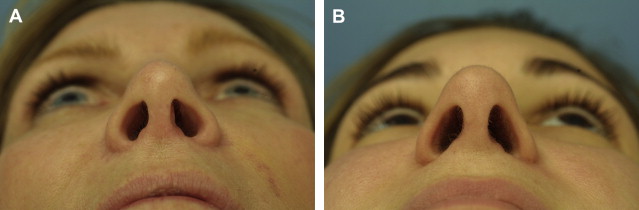

Before dividing any cartilage, I make sure it is extensively released from the vestibular skin to allow for cartilage advancement. The location of the division determines the overall effect on the nasal tip: projection, definition, rotation, and nasal length ( Fig. 2 ). Division at the medial crural feet, followed by a medial crural overlay, will deproject and counter-rotate the tip and can be used to decrease excessive flaring of the medial crural footplate. Midmedial crus division can be used to adjust columellar asymmetries in addition to deprojection and counter-rotation with a medial crural overlay. Division at the junction of the medial and intermediate crus will result in tip deprojection, vertical shortening of the infratip lobule, and a diminished hanging infratip lobule or intermediate crura. At the dome or in the intermediate crus, division and overlap, or intermediate crural overlay (ICO), will deproject the tip and produce greater acuity of the domal arch and therefore lobular refinement. Asymmetric division, when needed, can improve lobule symmetry here with sutures concealed within the infratip. Division and overlay in the midlateral crus is a powerful maneuver for producing rotation and deprojection through a lateral crural overlay. When lobular contour is acceptable, division at the hinge area will deproject and rotate the tip. In all of these techniques, we reconstruct the M-arch with sutures to secure structural integrity and normal anatomy. The cut ends of cartilage are overlapped from 2 mm up to 6 mm in some cases and are secured with 6-0 nylon mattress sutures. One set of buried sutures is placed to set the length of the overlap. A second set of buried sutures is used to set the axis of the neo-arch. Alternatively, one can use 4-0 Vicryl sutures in the lateral crus to fixate the cartilage segments through the underlying vestibular skin. This can be used to overcome the technical challenge of burying sutures in this location ( Fig. 3 ). To avoid inflaring or collapse of the arch on contraction of the skin–soft tissue envelope, overlapping suture fixation must be used. Generally I use the cartilage segment closest to the lobule as the overlying segment.