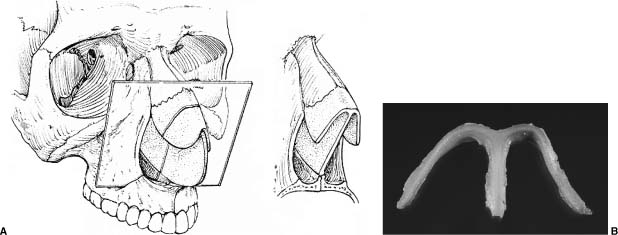

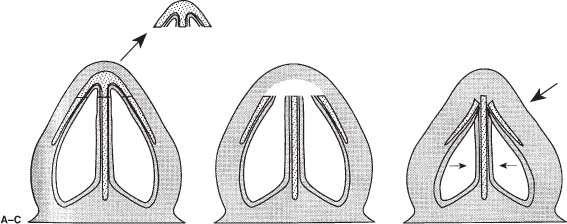

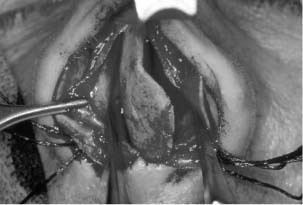

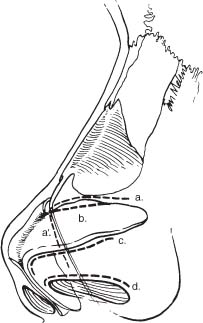

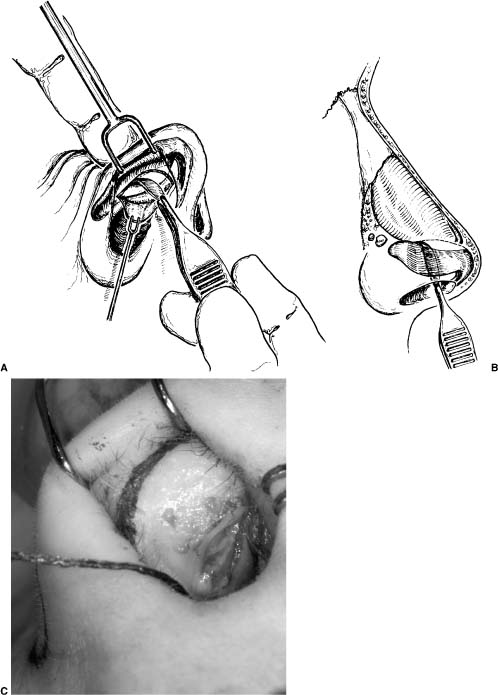

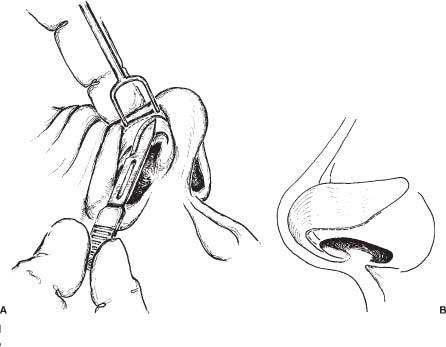

Chapter 5 Rhinoplasty is a complex operation that requires the surgeon to account for variances in anatomy, facial aesthetics, tissue healing, and the long-term effects of scar contracture. Surgeons who follows their patients long term will be able to assimilate valuable experience that can be used to help determine the surgical techniques that will be most successful in patients with any given anatomic deformity. Precise record keeping, noting exactly what was done at surgery, allows the surgeon to go back and correlate a successful outcome with a particular technique or a poor outcome with a less reliable technique. Successful rhinoplasty is all about analyzing the patient’s primary deformities, knowing what the underlying anatomy will likely be, and choosing a specific technique that will give the patient the best chance for a good, long-term outcome. The surgeon must be able to execute the operation properly, minimize tissue trauma, and provide appropriate postoperative care. One of the most complex aspects of rhinoplasty is determining how the effects of scar contracture will effect healing of the nose, which requires a high level of experience and judgment. The philosophy of most rhinoplasty surgeons is moving away from excision of tissue and toward repositioning or stabilizing the existing structures.1–3 Patients with good structural support tend to heal more favorably and are better able to withstand the forces of scar contracture over time. The nose can be divided into three anatomic regions: the upper, middle, and lower third. The upper third is composed primarily of the nasal bones and overlying skin, the middle third is composed of the upper lateral cartilages and septum, and the lower third is composed primarily of the lower lateral cartilages and nasal septum. The skin covering the nose varies in thickness, with the skin of the nasion and tip being relatively thick. There is thinner skin over the nasal bones and middle vault. The nasal bones tend to be relatively thin and are connected via a suture line to the thicker bone of the nasal process of the frontal bone and ascending process of the maxilla.4 The nasal bones tend to be thinnest at the anterocaudal margin where they meet the upper lateral cartilages. The upper lateral cartilages overlap the caudal aspect of the nasal bones and connect to the undersurface of the nasal bones. This overlap of cartilage and bone is critical to the support of the middle vault, and disruption of this connection can result in deformity or collapse of the upper lateral cartilages. In the middle nasal vault, the upper lateral cartilages come up to meet the dorsal aspect of the nasal septum and form a T shape or Y configuration on cross section.5 This T shape creates a horizontal component to the middle vault that accounts for the trapezoidal shape and much of the width of the middle third of the nose (Fig. 5-1). Patients with an excessively wide middle nasal vault tend to have a broader horizontal component to the middle third. On the other hand, patients with a narrow nose tend to have more of a triangular shape to the middle vault, and the upper lateral cartilage has little or no horizontal component as it meets the dorsal septum. Asymmetry of the dorsal aspect of the nasal septum may result in asymmetry of the upper lateral cartilages as they meet the deviated dorsal septum. This may create a deviated appearance to the middle third of the nose. Patients with short nasal bones, long upper lateral cartilages, and a projecting nose are at increased risk for collapse of the middle vault. Simple palpation of the nasal bone length can help predict patients who will be at higher risk of postoperative middle vault collapse. Sheen and Sheen3 referred to these patients as those with the “narrow nose syndrome.” When dorsal hump reduction is performed, there may be loss of medial support, and the upper lateral cartilages can collapse inferomedially (Fig. 5-2).5 On the other hand, patients with long nasal bones and short upper lateral cartilages rarely have problems with middle vault collapse because the upper laterals are well supported. Spreader grafts can be used to reconstruct the middle vault in patients who have short nasal bones. The integrity of the support mechanisms of the nose is critical to the preservation of favorable nasal tip contour. The major support mechanisms of the nose include the inherent strength and integrity of the lower lateral cartilages, the attachment of the upper lateral cartilages to the lower lateral cartilages (scroll or recurvature), and the fibrous attachment between the feet of the medial crura and the caudal septum.4 The septal cartilage should also be considered a major support mechanism of the nose as it is critical to supporting the lower two thirds of the nose. Minor support mechanisms include the interdomal ligament, nasal spine, and attachments of the lower lateral cartilages to the overlying skin and soft tissue. The surgeon should attempt to preserve these support mechanisms or strengthen them to preserve favorable nasal contour. The caudal aspect of the septum and its relationship to the nasal tip cartilages is also critical to nasal tip support and contour. FIGURE 5-1 (A) Cross section taken through the middle vault near the osseocartilaginous junction. The trapezoidal shape of the middle nasal vault is partly due to the horizontal or T-shaped component of the upper lateral cartilages as they meet the dorsal margin of the nasal septum. (B) Cross section of a fresh cadaver specimen that demonstrates a prominent horizontal component to the middle nasal vault. (From Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault. Op Tech Plast Reconst Surg 1995;2;16–30, with permission.) FIGURE 5-2 (A) Dorsal hump is removed with some intranasal mucosa. (B) The medial support of the upper lateral cartilages is excised. (C) After dorsal hump removal in patients with short nasal bones, the long flail upper lateral cartilages can collapse inferomedially because of lack of medial support. The lower lateral cartilages typically consist of three different components: the conjoined medial crura, the lateral crura, and the divergent intermediate or middle crura. The medial crura parallel each other and the intermediate crura diverge to meet the domes and lateral crura, which lie in a more horizontal plane. The divergent intermediate crura correspond to the favorable curvature of the columellar-lobular angle (Fig. 5-3). Obliteration of this divergence can result in blunting of the columellar-lobular angle. In many patients, there is a notch near the junction of the intermediate and lateral crura. This notch frequently corresponds to the overlying soft tissue triangle or facets. Patients with prominent notches frequently have prominent facets. The lateral crura typically project laterally toward the pyriform aperture and the sesamoid cartilages. In some patients, the lateral crura take on a more cephalic orientation as the cartilages follow the middle nasal vault instead of passing toward the pyriform aperture (Fig. 5-4). Patients with cephalic positioning of the lateral crura are at high risk for lateral wall weakness and external nasal valve collapse because there is insufficient lateral wall support. Treatment requires the addition of support to the lateral wall in the form of alar batten grafts or equivalent lateral wall grafts. FIGURE 5-3 The lower lateral cartilages consist of the medial crura, intermediate crura, and lateral crura. The intermediate crura diverge to meet the lateral crura, which lie in a more horizontal plane and form the columellar/lobular angle. Obliteration of this divergence can blunt the columellar/lobular angle. (A) Basal view showing divergent intermediate crura. (B) Lateral view showing subtle curvature of the columellar/lobular angle as the medial crura meet the intermediate crura. Precise nasal analysis and diagnosis of variant nasal anatomy is critical to success in rhinoplasty surgery. Surgeons choose surgical techniques based on the patient’s preoperative deformities and then determine the most effective technique for correction of the deformity. When performing nasal analysis, the surgeon should be able to define the external nasal deformities and predict the underlying nasal anatomy. This provides the most helpful information for determining the appropriate surgical technique. FIGURE 5-4 (A) Lateral crura typically move laterally toward the pyriform aperture. (B) Cephalically positioned lateral crura. Note how the lateral crura follow the middle nasal vault in a more cephalic orientation. We begin our analysis by assessing the surrounding facial features and determining whether or not the nose is in balance with the rest of the face. The nose should be approximately one-third the length of the face and one-fifth the horizontal width. The surgeon should assess the projection of the chin and configuration of the forehead. Good chin projection will better balance with a well-projected nose, whereas a retrognathic chin will give the illusion of an overprojected nose despite normal projection. When operating on an overprojected nose, patients with an underprojected chin can benefit from increasing chin projection to better balance the nose. This relationship is particularly important in patients with thick skin and an overprojected nose, as thick skin does not redrape properly if the nose is made much smaller. Creating a good relationship between the nose, forehead, and glabella allows a defined nasal starting point and good facial balance. Patients with a flat forehead and glabella tend to lack a defined nasal starting point, making the nose look overly long. One should avoid augmenting the radix in patients with a flat forehead and a relatively flat glabella. In the female, the nasal starting point should be at the level of the superior palpebral fold with the eyes in forward gaze. The nasal starting point can be slightly higher in male patients. Nasal tip projection can be analyzed in many different ways. The Goode6 method of determining tip projection sets ideal tip projection at 0.55 of the distance from the nasion to the tip-defining points. In another method, Crumley and Lanser7 set ideal tip projection as a relationship to a vertical line dropped from the nasion to the nasal base. Byrd and Hobar8 look at many nasal parameters as a relationship to several relatively uniform facial measurements. After assessing tip projection with these methods, surgeons should use their aesthetic sense to determine what would be an appropriate tip projection. Surgeons should balance the nose with the chin projection and forehead configuration. Noses with adequate projection tend to look better and more refined on frontal view. Decreasing nasal projection will decrease lateral wall shadowing and tend to create a flatter, less defined look on frontal view. It is critical to focus on enhancing the frontal view, as this is the most important view. Preoperative photography of the patient should be attained prior to performing aesthetic and functional rhinoplasty. Standard rhinoplasty views include the frontal, right and left lateral, right and left oblique, and basal views. Photographs should be taken using standard lighting and standard magnification and reproducible positioning of the head to allow precise comparison from pre- to postoperative states. Harsh or uneven lighting is the most common flaw in patient photography. Nonuniform lighting tends to create unwanted shadows and poor representation of true facial contours. We prefer to use a neutral background color such as light blue to enhance skin tones. When planning cosmetic rhinoplasty, we recommend doing computer imaging to demonstrate to the patient the realistic changes that can be performed with good reliability. The imaging can educate the patient on why the nose may need to be made larger with dorsal augmentation or radix augmentation to improve nasal balance and maximize the look on the frontal view. These changes are particularly important in patients with thicker skin and those who have undergone previous surgery. When performing imaging it is critical to image in a fashion that portrays realistic expectations to the patient. Some patients have significant limitations in their soft tissues or support structures that will allow only a modest degree of improvement. When imaging patients with such limitations, it is imperative that the surgeon show representative images to avoid unrealistic expectations. We prefer to underimage and show the patient a proposed outcome that we believe we can achieve with a high level of confidence. Nasal analysis performed on the frontal view should assess nasal symmetry and length; the width of the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the nose; tip contour; width of the alar base; prominence of the infratip lobule; and alar flare. The surgeon should assess the continuity of the brow-tip aesthetic line and determine if it is unbroken as it passes from the medial brow to the lateral wall of the nose to the tip-defining points. Ideally, the female nose should be slightly wider at the radix, narrow slightly at the middle third, and then be slightly wider at the nasal tip (Fig. 5-5). On lateral view, the radix corresponds to the soft tissue depths of the nasofrontal angle. The surgeon should assess the radix to determine if it is overly deep or shallow. An overly deep radix gives the nose a shorter appearance with a dorsal hump (Fig. 5-6). A shallow radix gives the appearance of a longer nose with a poorly defined nasal starting point. Evaluation of the lateral view should also assess the presence of a dorsal hump, tip/supratip relationship, tip projection, lobule configuration, alar/columellar relationship, nasolabial angle, and nasal length. FIGURE 5-5 Female nose on frontal view showing slight width in the radix with narrowing in the middle vault and slight widening in the lower nasal tip. This subtle hourglass appearance is ideal in the female patient. Analysis of the basal view should reveal symmetry of the nasal base, the infratip lobule/columella relationship, tip width, alar flare, width of the nasal base, and tip projection. The surgeon should also identify deviations of the caudal septum, flaring medial crural footplates, or internal recurvature of the lateral crura. FIGURE 5-6 Patient with a deep radix that gives the nose a shorter appearance with a more pronounced dorsal hump. Elevation of the radix with conservative hump reduction would be ideal in this patient. Preoperative diagnosis of factors contributing to nasal obstruction is critical to provide maximal functional results as well as a favorable aesthetic result. The surgeon should perform a thorough intranasal examination including an endoscopic exam in patients with nasal symptoms. Anterior rhinoscopy should be performed before and after nasal decongestion with a vasoconstrictive agent. The entire septum should be examined; the size of the turbinates should be assessed, and the presence of nasal polyps and the status of the internal and external nasal valve should be noted. Procedures typically performed to improve nasal function include septoplasty, nasal valve surgery, and turbinoplasty. Septoplasty is usually performed to correct deviations in the bony or cartilaginous septum, or to harvest septal cartilage for grafting purposes. Septoplasty can be performed via several different approaches. The different approaches include the Killian, hemitransfixion, full transfixion, or external rhinoplasty. Selection of the approach to the nasal septum depends on the goals of the surgery. A Killian incision is made cephalic to the caudal margin of the septum and is made on one side of the septum. The hemitransfixion incision can be used when the surgeon must correct a deviation or modify the caudal aspect of the nasal septum. This incision is made at the caudal aspect of the septum and goes through the mucosal flap on only one side of the septum. The full-transfixion incision is made through the mucosal flaps on both sides of the caudal aspect of the septum. This incision results in significant loss of support if extended down to the base of the medial crural footplates, and is one method for decreasing projection in the overprojected nasal tip. The external rhinoplasty approach to the nasal septum can be used in cases requiring alteration of the caudal margin of the septum. In this case, once the lower lateral cartilages are dissected, the medial crura are dissected apart and the caudal septum is identified. The mucoperichondrial flaps can then be dissected, and both sides of the septal cartilage can be completely exposed. If additional exposure is required, the upper lateral cartilages can be freed from the septum to gain maximal exposure of the entire cartilaginous septum. This approach is ideal for correcting severe caudal septal deviations (Fig. 5-7). FIGURE 5-7 Exposure of a severe caudal septal deviation via the external rhinoplasty approach after dissecting between the medial crura and freeing the upper lateral cartilages from the dorsal margin of the septum. Once exposure of the septum is achieved, deviated portions of the septum can be excised, leaving an intact L-shaped septal strut consisting of at least 1.5 cm of septal cartilage both caudally and dorsally. The surgeon should keep a stable connection between the dorsal cartilaginous septum and the bony septum (ethmoid plate) to avoid loss of support in the middle nasal vault. Septal support can also be maximized by leaving a fibrous connection between the inferior aspect of the caudal aspect of the septum to the nasal spine and maxillary crest. In some cases, correction of deviations of the caudal septum can be corrected by freeing the caudal septum from the nasal spine and maxillary crest, trimming excess cartilage, and resuturing the caudal septum to the periosteum about the nasal spine and maxillary crest. In many cases, the concave side of the deviation may require light cross-hatching to eliminate memory of the cartilage and allow straightening. In some cases, the maxillary crest itself is deviated, obstructing the airway. In these cases, the obstructing portion of the maxillary crest can be trimmed or burred down with a rotating power burr. Rhinoplasty can be performed using one of four basic approaches. These approaches require the use of a marginal, intercartilaginous, intracartilaginous, or transcolumellar incision (Fig. 5-8). Endonasal approaches include nondelivery approaches and delivery approaches. Nondelivery approaches include the cartilage-splitting approach and retrograde technique. These techniques are ideal for patients requiring minimal changes to nasal tip contour using conservative excisional techniques. In the cartilage-splitting approach, an intracartilaginous incision is made through the vestibular mucosa and underlying cephalic margin of the lateral crura to achieve a conservative volume reduction of the lateral crura (Fig. 5-9). When performing this approach it is critical to recognize the anatomy of the lateral crura to execute precise and conservative volume reduction. In the retrograde approach, an intercartilaginous incision is made and the vestibular mucosa is dissected caudally to expose the cephalic margin of the lateral crura, which can then be trimmed. The intercartilaginous incision also provides access to the nasal dorsum (Fig. 5-10). In this approach, the cephalic margin of the lateral crura can be visualized and then precisely trimmed. In both of these approaches, the lateral crura are left attached to the overlying soft tissue, limiting dissection of the lower lateral cartilages. These approaches are good for patients who require minimal volume reduction of the lateral crura and do not require alteration of the domal angle of the lower lateral cartilages. These patients typically have a symmetric nasal base contour, which approximates an equilateral triangle. Patients with an obtuse domal angle and trapezoidal shape on base view require a delivery approach or external rhinoplasty approach to change the shape of the nasal base. FIGURE 5-8 Incisions used in rhinoplasty. Shown are the intercartilaginous incision (retrograde and delivery approach), intracartilaginous incision (cartilage-splitting approach), marginal incision (delivery and external approach), and the transcolumellar incision (external approach). a, intercartilaginous; a’, transfixion extension of intercartilaginous incision; b, intracartilaginous incision (cartilage-splitting incision); c, marginal incision; d, rim incision. It is very rare that a rim incision is ever made, as it tends to deform the alar rim. The delivery approach involves creation of bilateral chondrocutaneous flaps using marginal and intercartilaginous incisions. The marginal incision is made along the caudal margin of the lateral crura, and the intercartilaginous incision is made between the cephalic margin of the lateral crura and the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage (Fig. 5-11). While making the intercartilaginous incisions, the knife can be used to elevate the soft tissues of the middle nasal vault. Once these incisions are made, the lower lateral cartilage are dissected away from the overlying skin and soft tissue, and the lateral crura can be delivered into the field using a blunt, flat instrument (Fig. 5-12). Good exposure of the domes can be achieved with this approach, allowing placement of dome sutures or other tip work. In some cases the intercartilaginous incision may need to be extended to follow the caudal margin of the septum to gain additional exposure. The external rhinoplasty approach requires the use of an inverted-V midcolumellar incision and bilateral marginal incisions (Fig. 5-13). The midcolumellar incision should be made midway between the top of the nostril and the base of the nose. It is better to err in making the incision lower as opposed to too high on the columella, as higher incisions are more likely to be visible on the frontal view. If there is significant flaring of the medial crural footplates, the columellar incision may impinge on this area. If this is the case, the incision will be easier to close if the footplates are conservatively approximated. The marginal incisions are made at the caudal margin of the lateral crura (Fig. 5-14). The columellar extension of the marginal incision is made just caudal to the caudal margin of the medial crura to avoid damaging the medial crura (Fig. 5-15). Converse scissors can be advanced under the columellar flap, taking great care not to damage the medial crura (Fig. 5-16). Special care should be taken not to bevel the columellar incision, as this will make it more difficult to close at the end of the operation. The columellar flap is elevated in the submuscular plane, leaving the subcutaneous tissues attached to the under-surface of the flap. Three-point countertraction can be used to help dissect the domes and lateral crura (Fig. 5-17). Dissection over the lateral crura should be performed in the submuscular plane immediately adjacent to the surface of the lateral crura (Fig. 5-18). Dissection over the middle vault should also be submuscular to avoid excessive bleeding. Elevation of this flap provides maximal exposure of the lower lateral cartilages and middle nasal vault. A Joseph periosteal elevator is used to elevate the periosteum off of the nasal bones to avoid damaging the thin dorsal skin. Leaving the periosteum on the nasal bones will decrease the thickness of the dorsal skin and can result in atrophic changes (telangiectasia, etc.) and inadequate dorsal camouflage. Skin flap elevation should be just sufficient to allow the necessary surgical maneuvers to accomplish the proposed contour changes. If the surgeon plans on performing dorsal augmentation or radix augmentation, we recommend leaving a narrow pocket over the dorsum or radix. FIGURE 5-9 Cartilage-splitting approach to the lateral crura. (A) Note how the intracartilaginous incision is made close to the cephalic margin of the lateral crura to avoid excessive volume reduction. (B) The cephalic trim is performed, decreasing the tip bulbosity, and then the mucosa is preserved and resutured. (C) The cartilage splitting incision goes through the cartilage at the site of the cephalic trim. (From: Toriumi DM, Becker DG: Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999, with permission.) FIGURE 5-10 (A) An intercartilaginous incision is made between the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage and cephalic margin of the lateral crura. (B) Note how the incision is made just caudal to the upper lateral cartilage at the scroll region. (C) A knife can then be used to dissect the soft tissue off of the underlying middle vault cartilages. This dissection should be deep to the muscle layer of the nose. Dissection over the bone should be subperiosteal. (D) A slight extension of the incision can be made over the anterior septal angle to provide additional exposure. (E) A converse retractor can be used to visualize the middle and upper nasal vaults. (F) Intraoperative view of intercartilaginous incision. (From Toriumi DM, Becker DG. Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999, with permission.) Once surgical maneuvers are performed, special attention should be paid to the closure of the midcolumellar incision to maximize scar camouflage. We use a single midline subcutaneous 6-0 PDS (polydioxanone, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) suture to take tension off of the skin closure. Then we maximize skin edge eversion using 7-0 nylon vertical mattress sutures. We typically remove these sutures on the seventh postoperative day. There may be increased tip edema associated with the external rhinoplasty approach. However, we have found that dissection in the submuscular plane minimizes bleeding and preserves the venous and lymphatic outflow to the skin flap and can minimize edema. FIGURE 5-11 Delivery approach. (A) Execution of the marginal incision. (B) Note how the incision is made at the caudal margin of the medial and lateral crus. FIGURE 5-12 Delivery approach. (A) Scissors can be used to dissect the soft tissue from the surface of the lateral crura. (B) The lower lateral cartilages can then be delivered into the field allowing good exposure of the lateral crura and domes. (From Toriumi DM, Becker DG, Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999, with permission.) After the structures of the nose are exposed and assessed, the surgeon can determine the plan for profile alignment. If the patient has a dorsal convexity, it may be prudent to reduce the dorsum. The objective is to leave the dorsum as high as possible yet allow sufficient reduction to create a favorable tip/supratip and dorsum-to-radix relationship. There is a tendency to overreduce the bony dorsum, leaving the patient with inadequate dorsal height. It is preferable to preserve a high dorsal profile, as this will make the nose appear more refined on frontal view. If the patient has a dorsal hump and the radix is low, a radix graft can be placed into a tight pocket over the nasofrontal angle to create a straighter profile while leaving the dorsum higher (Fig. 5-19). The graft should be placed into a narrow subperiosteal tunnel over the nasofrontal angle (Fig. 5-20). Typically, these are smaller, lightly crushed cartilage grafts that are less likely to be palpable or visible. We usually place radix grafts at the end of the operation to minimize the chance of displacement. When planning to raise the radix with a graft, the dorsal hump reduction should be more conservative. FIGURE 5-13 Inverted-V midcolumellar incision made midway between the top of the nostrils and the base of the nose. Special care should be taken not to make this incision too high on the columella, otherwise it may be visible on the frontal view.

RHINOPLASTY

ANATOMY

ANALYSIS AND DIAGNOSIS

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

NASAL SEPTUM

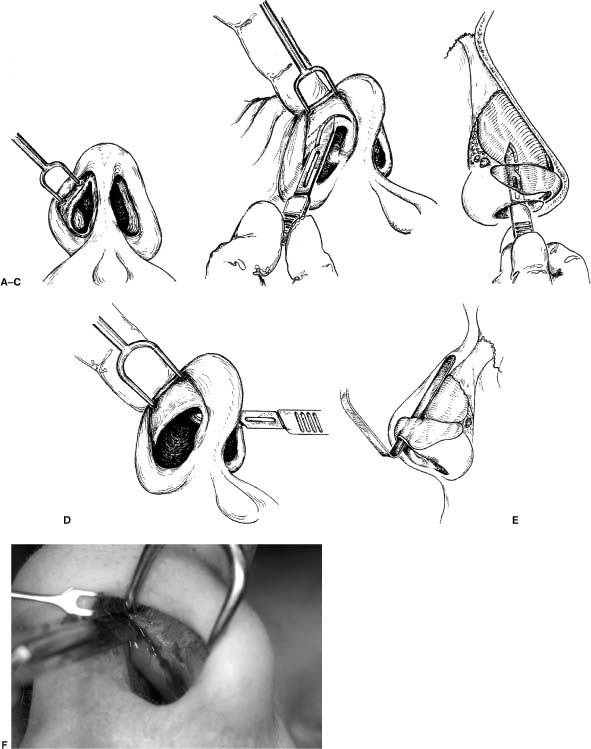

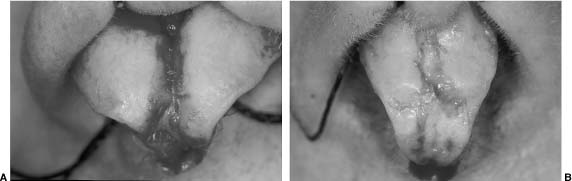

INCISIONS AND APPROACHES TO THE NOSE

PROFILE ALIGNMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

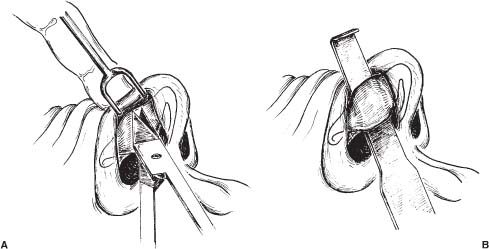

Full access? Get Clinical Tree