15 Retropubic Operations for Stress Urinary Incontinence

Few data differentiate one retropubic procedure from another, although all have advantages and disadvantages. Historically, the three most studied and popular retropubic procedures are the Burch colposuspension, the Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz (MMK) procedure, and the paravaginal defect repair. We no longer perform the MMK procedure, so this operation will not be described. We prefer the Burch colposuspension for urodynamic stress incontinence with bladder neck hypermobility and adequate resting urethral sphincter function and combine it with a paravaginal defect repair, when the patient has stage 2 or 3 anterior vaginal prolapse or when a concurrent sacrocolpopexy is required. The surgical techniques described herein are contemporary modifications of the original operations: Tanagho (1976) described the modified Burch colposuspension; the paravaginal defect repair was described by Richardson et al. (1981) and Shull and Baden (1989) (paravaginal repair) and by Turner-Warwick (1986) and Webster and Kreder (1990) (vaginal obturator shelf repair). Although less critically studied, the paravaginal defect repair is regionally popular and widely performed in the United States. The operations described do not represent one correct technique but a commonly used and proven method.

This chapter describes only retropubic suspension procedures that use an abdominal wall incision for direct access into the space of Retzius. The use of laparoscopy and mini-incision laparotomy to enter the retropubic space and perform these and similar procedures is expanding, both in terms of clinical experience and research. The reader is encouraged to see Chapter 17 for a thorough critique of the use of operative laparoscopy for treatment of urinary incontinence and and pelvic organ prolapse.

INDICATIONS FOR RETROPUBIC PROCEDURES

Retropubic urethrovesical suspension procedures are indicated for women with the diagnosis of urodynamic SUI and a hypermobile proximal urethra and bladder neck. These procedures yield the best results when the urethral sphincter is capable of maintaining a watertight seal at rest but cannot withstand the unequal transmission of abdominal pressure to the proximal urethra, relative to the bladder, with straining. Although retropubic procedures can be used for intrinsic sphincter deficiency with urethral hypermobility, other more obstructive operations, such as a sling, probably yield better long-term results (see Chapter 16).

To diagnose urodynamic SUI, clinical and urodynamic (simple or complex) tests must be performed to evaluate bladder filling, storage, and emptying. Clinically, the urethra is shown to be incompetent by visually observing simultaneously the loss of urine and increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Urodynamic or radiologic methods may also be used for diagnosis. Abnormalities of bladder-filling function, such as overactive bladder, can coexist with urethral sphincter incompetence in up to 30% of patients and may be associated with a lower cure rate after retropubic surgery.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Burch Colposuspension

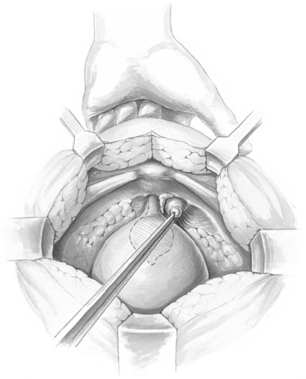

After the retropubic space is entered, the urethra and anterior vaginal wall are depressed. No dissection should be performed in the midline over the urethra or at the urethrovesical junction, thus protecting the delicate musculature of the urethra from surgical trauma. Attention is directed to the tissue on either side of the urethra. The surgeon’s nondominant hand is placed in the vagina, palm facing upward, with the index and middle fingers on each side of the proximal urethra. Most of the overlying fat should be cleared away, using a swab mounted on a curved forceps. This dissection is accomplished with forceful elevation of the surgeon’s vaginal finger until glistening white periurethral fascia and vaginal wall are seen (Fig. 15-1). This area is extremely vascular, with a rich, thin-walled venous plexus that should be avoided, if possible. The position of the urethra and the lower edge of the bladder is determined by palpating the Foley balloon and by partially distending the bladder to define the rounded lower margin of the bladder as it meets the anterior vaginal wall.

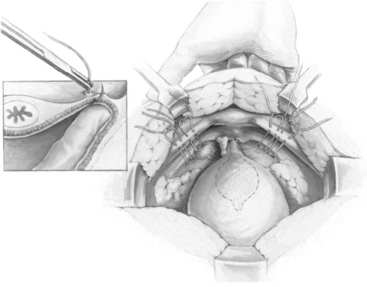

Once dissection lateral to the urethra is completed and vaginal mobility is judged to be adequate by using the vaginal fingers to lift the anterior vaginal wall upward and forward, sutures are placed. No. 0 or 1 delayed absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures are placed laterally as far in the anterior vaginal wall as is technically possible. We apply bilaterally two sutures of No. 0 braided polyester on an SH needle (Ethibond; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ), using double bites for each suture. The distal suture is placed approximately 2 cm lateral to the proximal third of the urethra. The proximal suture is placed approximately 2 cm lateral to the bladder wall at or slightly proximal to the level of the urethrovesical junction. In placing the sutures, one should take a full thickness of vaginal wall, excluding the epithelium, with the needle parallel to the urethra (Fig. 15-2, inset). This maneuver is best accomplished by suturing over the surgeon’s vaginal finger at the appropriate selected sites. On each side, after the two sutures are placed, they are passed through the pectineal (Cooper’s) ligament so that all four suture ends exit above the ligament (Fig. 15-2). Before the sutures are tied, a 1 × 4 cm strip of Gelfoam may be placed between the vagina and obturator fascia below Cooper’s ligament to aid adherence and hemostasis.

Paravaginal Defect Repair

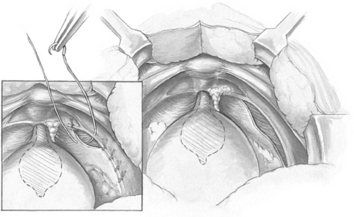

The object of the paravaginal defect repair is to reattach, bilaterally, the anterolateral vaginal sulcus with its overlying endopelvic fascia to the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles and fascia at the level of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis. The retropubic space is entered, and the bladder and vagina are depressed and pulled medially to allow visualization of the lateral retropubic space, including the obturator internus and levator muscles and the fossa containing the obturator neurovascular bundle. Blunt dissection can be carried dorsally from this point until the ischial spine is palpated. The arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis is often visualized as a white band of tissue running over the pubococcygeus and obturator internus muscles from the back of the lower edge of the symphysis pubis toward the ischial spine. A lateral paravaginal defect representing avulsion of the vagina off the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis or of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis off the obturator internus muscle may be visualized (Fig. 15-3).

The surgeon’s nondominant hand is inserted into the vagina. While gently retracting medially the vagina and bladder, the surgeon elevates the anterolateral vaginal sulcus. Starting near the vaginal apex, a suture is placed, first through the full thickness of the vagina (excluding the vaginal epithelium) and then deep into the obturator internus fascia or arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, 1 to 2 cm anterior to its origin at the ischial spine. After this first stitch is tied, additional (four or five) sutures are placed through the vaginal wall and overlying fascia and then into the obturator internus at about 1-cm intervals toward the pubic ramus (Fig. 15-3, inset). The most distal sutures should be placed as close as possible to the pubic ramus, into the pubourethral ligament; alternatively, Burch colposuspension sutures can be placed bilaterally at the level of the bladder neck and urethra if the patient has SUI. No. 2-0 or 0 nonabsorbable suture on a medium-sized, tapered needle is usually used for the paravaginal repair.

This procedure leaves free space between the symphysis pubis and the proximal urethra but secures support so that rotational descent of the proximal urethra and bladder base is prevented with sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure. According to Turner-Warwick (1986), the procedure avoids overcorrection and fixation of the periurethral fascia, which might compromise the functional movements of the urethra and bladder base and lead to obstruction and voiding difficulty. This principle may explain why the paravaginal defect repair usually results in spontaneous voiding on the first or second postoperative day. In fact, the vaginal obturator shelf repair has been used to correct patients with dysfunctional voiding symptoms after previous retropubic surgery.

CLINICAL RESULTS

Only a few studies have been done assessing the paravaginal defect repair for SUI. Early studies using subjective outcome measures reported that over 90% of women were continent after this procedure. However, in a prospective randomized trial, Columbo et al. (1996) found that only 61% of women were continent 3 years after a paravaginal defect repair compared with 100% of women who were continent after a Burch colposuspension. We currently believe that the paravaginal defect repair should be used for anatomic correction of anterior vaginal wall prolapse but not as primary treatment of SUI.

In an excellent study, Eriksen et al. (1990) reported 91 women with urodynamically proved SUI, with or without bladder stability, who had undergone Burch colposuspension. Urodynamic evaluation was done on 76 patients after 5 years. Stress incontinence was cured in 71% of the patients with preoperative stable bladders and in 57% of those with stress incontinence and detrusor overactivity, a nonsignificant difference. After 5 years, only 52% of the study group was completely dry and free of complications; about 30% needed further incontinence therapy.

Several studies have been done that assessed women more than 10 years after undergoing a Burch procedure. Alcalay et al. (1995)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree