The eyes are the most captivating feature of the face. Many of the early signs of aging occur in the periocular region. This article focuses on surgical rejuvenation of the upper eyelid with an emphasis on the eyelid anatomy, aging of the eyes, clinical evaluation, surgical technique, and postoperative complications. The paradigm has shifted to a more conservative resection of skin, muscle, and fat to preserve fullness to the upper eyelid that portrays youthfulness.

The eyes are the most captivating feature of the face. Furthermore, attractive eyes are an important feature of the youthful face. Although attention is drawn to the eyes, the surrounding structures that frame the eye are key contributors to facial beauty. The frame of the eye extends down to the lower eyelid-cheek junction and up to the upper eyelid–brow unit. Thus, the periocular region is a complex that should be broadly defined to include the eyebrow and midface. It is a surgeon’s job to carefully analyze the underlying anatomy to determine the surgical approach to achieve the best aesthetic result.

The youthful upper eyelid is full, not hollow or overskeletonized. There is a crisp upper lid crease with elastic support of the underlying soft tissue, creating a smooth, taut pretarsal and preseptal upper eyelid. The eyebrow is often addressed in conjunction with the upper eyelid in upper face rejuvenation. This article focuses solely on surgical rejuvenation of the upper eyelid. The goal of rejuvenation of the upper eyelid should be a more youthful but natural-appearing result.

Upper eyelid surgery is the most requested and performed facial rejuvenation surgery in the United States. The excision of the eyelids dates back 2000 years. The cauterization of excess eyelid skin to reduce drooping is described in the Sanskrit document, the Sushruta . American surgeons began to write about cosmetic surgery in 1907, with Conrad Miller’s Cosmetic Surgery and the Correction of Feature Imperfections . Over the subsequent decades, surgeons advocated the removal of herniated fat pads and orbicularis oculi muscle excision. Over the past 20 years, the emphasis on technique has shifted to conservation of fat, skin and muscle excision to avoid a deep, hollow, and skeletonized appearance to the eyelids.

Eyelid anatomy

The position and form of the eyebrow has a deep impact on the appearance of the upper eyelid and eye below. A precise analysis of eyebrow position and form is a critical first step in the evaluation of the upper eyelids, a full analysis of which is beyond the scope of this article. A few salient points are discussed. The female brow is arched with the most superior aspect of the brow positioned directly above the lateral limbus. Laterally the brow sits above the orbital rim, and centrally there should be a high arch with a deep superior sulcus. The ideal position of the female brow differs from that of the male brow. The male brow is relatively straight, lying at the level of the orbital rim, and runs perpendicular to the nose with a minimal sulcus and a low subtle lid crease 8 mm above the lash line.

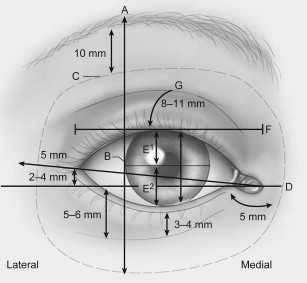

Fig. 1 depicts many anatomic relationships that must be understood when evaluating the eyelid and assessing what needs to be addressed to restore youthfulness. The lateral canthus is typically 2 to 4 mm superior to the medial canthus. The adult palpebral fissure averages 10 to 12 mm vertically and 28 to 30 mm horizontally. The distance from the lateral canthus to the orbital rim is typically 5 mm. At rest, the upper eyelid covers the superior limbus by 1 to 2 mm. The highest point of the upper lid margin is just nasal to a vertical line drawn through the center of the pupil. This contour should be noted preoperatively when evaluating patients for rejuvenation of the upper eyelid so it can be addressed during surgery to create a more aesthetic and appropriate lid position. The upper lid crease lies 8 to 11 mm above the lash line in whites but this varies with ethnic background. In Asians, the upper lid crease may be lower or absent owing to the lower insertion of the septum and variable or absent insertion of the levator aponeurosis into the upper lid skin.

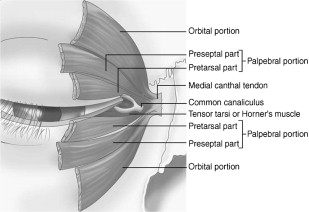

The layers of the upper eyelid can be separated into an anterior lamella and a posterior lamella. The anterior lamella is comprised of the thinnest skin of the human body and the orbicularis oculi muscle. The posterior lamella is comprised of the levator aponeurosis, tarsus, Müller muscle, and conjuctiva. Deep to the skin lies the orbicularis oculi muscle, which can be divided into an orbital portion and a palpebral portion. The palpebral portion is further subdivided into a pretarsal and preseptal portion lying over the tarsal plate and orbital septum, respectively ( Fig. 2 ).

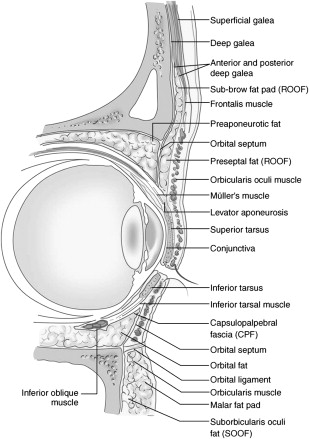

The postseptal fat of the superior orbit is divided into 2 compartments: the central (or preaponeurotic) and the medial (or nasal) fat pads separated by the trochlea and fascial strands from the Whitnall ligament. During upper eyelid surgery, surgeons must protect the trochlea to avoid superior oblique palsy or Brown syndrome. The medial fat pad is paler and denser and recognition of these subtle differences is crucial for successful blepharoplasty with fat excision. The lacrimal gland occupies the lateral compartment. The retro-orbicularis oculi fat (ROOF) pad is a submuscular fat pad that sits deep to the interdigitation of the frontalis and orbicularis oculi muscles ( Fig. 3 ).

Aging of the eyes

The appearance of the upper eyelid may be affected by changes in the eyebrow position. Lateral ptosis of the eyebrow may add to fullness of the upper eyelid compounding the effect of the existing skin redundancy. In severe cases, this may cause visual field loss. The hallmarks of upper eyelid facial aging are lateral hooding, dermatochalasis, and fat pseudoherniation in the medial aspect of the upper eyelids. The upper eyelids become more redundant due to excess eyelid skin and eyebrow descent. Rejuvenation of the upper eyelid is intended to elevate ptotic tissues and remove any tissue redundancy.

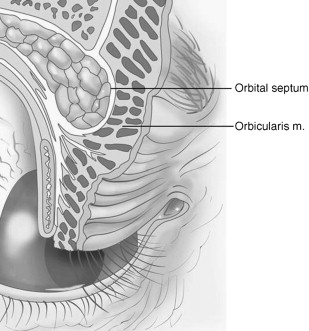

As a person ages, the loss of volume in the entire frontal region and loss of skin elasticity in the temporal region may account for brow ptosis, for those in whom this occurs. The tendency to counteract this by raising the eyebrows causes an accentuation of the hollowness under the eyes. This also leads to a decrease in the lateral fullness of the upper eyelid. When the frontalis is relaxed, the redundant skin hangs lower, and the distance between the eyebrow and eyelashes is shortened. The weakening of the orbital septum also causes herniation of the orbital fat ( Fig. 4 ). The lateral orbital region skin will develop rhytids, or crow’s feet. The orbicularis oculi muscle may hypertrophy over time, causing the preseptal portion to become redundant and roll over the firmly attached pretarsal orbicularis, exacerbating the redundancy. These factors all contribute to patients complaining of “looking tired, old, and not alert.”

Aging of the eyes

The appearance of the upper eyelid may be affected by changes in the eyebrow position. Lateral ptosis of the eyebrow may add to fullness of the upper eyelid compounding the effect of the existing skin redundancy. In severe cases, this may cause visual field loss. The hallmarks of upper eyelid facial aging are lateral hooding, dermatochalasis, and fat pseudoherniation in the medial aspect of the upper eyelids. The upper eyelids become more redundant due to excess eyelid skin and eyebrow descent. Rejuvenation of the upper eyelid is intended to elevate ptotic tissues and remove any tissue redundancy.

As a person ages, the loss of volume in the entire frontal region and loss of skin elasticity in the temporal region may account for brow ptosis, for those in whom this occurs. The tendency to counteract this by raising the eyebrows causes an accentuation of the hollowness under the eyes. This also leads to a decrease in the lateral fullness of the upper eyelid. When the frontalis is relaxed, the redundant skin hangs lower, and the distance between the eyebrow and eyelashes is shortened. The weakening of the orbital septum also causes herniation of the orbital fat ( Fig. 4 ). The lateral orbital region skin will develop rhytids, or crow’s feet. The orbicularis oculi muscle may hypertrophy over time, causing the preseptal portion to become redundant and roll over the firmly attached pretarsal orbicularis, exacerbating the redundancy. These factors all contribute to patients complaining of “looking tired, old, and not alert.”