27 Rectal Prolapse

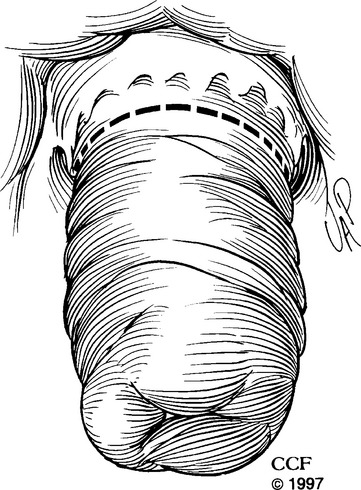

Rectal prolapse is full-thickness intussusception of the rectum toward and sometimes through the anal canal (Fig. 27-1). It can be internal (occult) or external to the anal sphincters and has been known for centuries and described in the medical literature; however, its cause is still unclear. Various operations have been described in the literature, but types of treatment and surgical approach still vary significantly from one institution to another. In this chapter we will discuss the etiology, epidemiology, clinical features, evaluation, common surgical techniques, results, and our experience regarding rectal prolapse.

Figure 27-1 Full-thickness rectal prolapse protruding through the anal canal.

(Reprinted with the permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

ETIOLOGY

“It is interesting to note that we still know so little about the cause of such a common condition.”

Although some questions have been answered, many aspects of rectal prolapse remain undetermined. Two main theories are known regarding the etiology of prolapse. In 1912, Moschcowitz proposed that rectal prolapse was a sliding hernia that protrudes through a defect in the pelvic fascia at the level of the anterior rectal wall. In 1968, a second theory was proposed by Broden and Snellman, who demonstrated with cinedefecography that full-thickness prolapse starts as an internal intussusception of the rectum with a lead point proximal to the anal verge. This theory was reinforced by Theuerkauf et al. (1970), who used radiopaque markers applied to the rectal mucosa to demonstrate prolapse secondary to intussusception. Today, rectal intussusception is accepted as the mechanism of rectal prolapse.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Up to 75% of patients with rectal prolapse are incontinent of stool. The precise pathophysiology behind incontinence is not completely defined, although some causative factors have been identified. Parks et al. (1977) demonstrated histologic evidence of denervation in pelvic muscle biopsies taken from patients who underwent postanal repair, the majority of whom also had rectal prolapse. This finding was confirmed by Neill et al. (1981), who performed electromyographic (EMG) studies of pelvic floor musculature and found denervation in incontinent patients, with and without rectal prolapse, but not in continent patients with rectal prolapse. Some patients with rectal prolapse have abnormal rectal sensation, which may improve following repair. Rectal prolapse itself may directly traumatize the anal sphincters. Anal resting pressures improve in some patients following prolapse surgery.

Constipation affects between 30% and 67% of patients with rectal prolapse. Constipation may be caused by intussusception of the rectum, colonic dysmotility, slow transit, or inappropriate puborectalis contraction. Prolapse repairs may increase or decrease constipation. Speakman et al. (1991) noted that division of the lateral ligaments during surgery appears to increase postoperative constipation, although whether it is due to colonic denervation remains uncertain.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Rectal prolapse is associated with comorbidities, including senile dementia, neurologic disorders, infectious disorders, connective tissue disorders, and bulimia nervosa. In addition, rectal prolapse is associated with straining, constipation, previous gynecologic surgery, and anal incontinence. Straining (or other unknown anatomic abnormalities) in men and younger women may push the anterior wall of the upper rectum against the anal canal and cause trauma, leading to ulceration, irritation, and bleeding. This is known as solitary rectal ulcer. At the Cleveland Clinic, Tjandra et al. (1993) reported that 18% of patients with prolapse reported straining and 42% had constipation, consistent with the range of 15% to 65% reported in the literature. Solitary rectal ulcer was found in 12% of patients with rectal prolapse. Previous gynecologic surgery is reported with rectal prolapse; we found that 35% of our patients had undergone a previous hysterectomy, and 38% of our patients were incontinent.

EVALUATION

Colonic transit marker studies may be important in patients with severe constipation. This test measures the time it takes for markers to traverse the colon. After patients swallow a set number of radiopaque markers, serial abdominal radiographs evaluate passage of these markers. Patients with prolonged colon transit time may benefit from colon resection with rectal preservation and rectopexy.

Anal manometry can be used to evaluate fecal incontinence. Matheson and Keighley (1981) found normal anal pressures in continent patients with rectal prolapse; however, incontinent patients had decreased resting and squeeze anal pressures. Many patients with prolapse-associated fecal incontinence have nerve damage believed to be due to traction injury of the pudendal nerves caused by the rectal prolapse. Continent prolapse patients may not show manometric or EMG signs of denervation. Anal manometry may identify patients who will have improved fecal continence after prolapse repair. Studies from Yoshioka et al. (1989) and Williams et al. (1991) showed that patients who remained incontinent after rectal prolapse repair had significantly lower preoperative resting and squeeze pressures than those whose incontinence improved postoperatively. Other studies, however, dispute the predictive value of anorectal physiology tests. Thus, anal manometry gives preoperative information that may identify patients who will have better outcomes but frequently does not change the clinical approach to the patient.

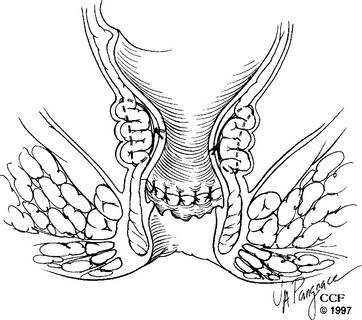

COMMON SURGICAL REPAIRS FOR PROLAPSE

Perineal Repairs

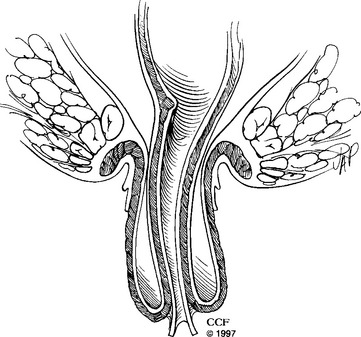

DELORME PROCEDURE

Although the Delorme procedure was first described in 1900, it was not commonly used until Uhlig and Sullivan reported their experience in 1979. Because the technique is simple and can be done under regional or local anesthesia, it is considered optimal for severely debilitated patients. We prefer to perform the operation with the patient in the prone jackknife position; however, it can also be done in lithotomy position. After the patient is positioned, the perineum and vagina are prepared with an aseptic solution. We use sutures applied in four places around the perianal skin to evert the anus. Other surgeons prefer retractors, such as Lone Star or Hill Ferguson, or Pratt bivalve speculums to enhance visualization. The operation is begun by injecting 1:100,000 epinephrine solution circumferentially into the submucosal plane just proximal to the dentate line. This delineates the dissecting plane and diminishes blood loss. Using electrocoagulation, the dissection starts in a circumferential manner 1 to 1.5 cm above the dentate line (Fig. 27-2), creating a plane between the submucosa and the internal anal sphincter. Once this plane is started, the free edge of mucosa and submucosa is tagged with sutures for ease in handling and creating traction for easier dissection. Continuing in a circumferential direction and using liberal amounts of injectable saline in the plane between the submucosa and the muscular cuff, the surgeon uses scissors to divide the attachments (we prefer fistula scissors) and to deliver the submucosa and mucosal cuff out of the rectum and anus. Penetrating blood vessels encountered during the dissection can be treated with electrocoagulation. Maintaining strict hemostasis is important during the dissection to avoid hematomas after the procedure. The dissection continues until the rectal mucosa cannot be pulled down any further. Usually, 10 to 15 cm can be mobilized. During this phase of the operation, we use copious amounts of antibiotic solution, such as tetracycline, to irrigate the surgical field. After the dissection is completed, the rectal muscle is plicated with suture, such as No. 2-0 Polyglactin 910 suture on a UR-6 needle (Vicryl; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). A total of eight sutures are spaced circumferentially for this plication. The dissected mucosa is excised, and the proximal line of resection is approximated to the distal incision line. Interrupted sutures of No. 2-0 Vicryl on a UR-6 needle work well for this circumferential suture line (Fig. 27-3).