Reconstruction of Partial Mastectomy Defects: Classifications and Methods

Albert Losken

Introduction

Reconstructive breast surgery is unique in its demand for ongoing refinement and continued restructuring to further improve outcome and patient satisfaction. Partial breast reconstruction is one of those areas where exciting new trends have been developed that have the potential to significantly change our practice strategies and the way we manage women with breast cancer. Although originally used to improve the cosmetic results by reconstructing breast conservation defects following radiation therapy, the shift now focuses more on recognizing the potentially unfavorable partial mastectomy defect and reconstructing this defect in an attempt to prevent the deformity. This combination allows removal of larger amounts of breast tissue with safer margins without compromising the cosmetic outcome. Women with breast cancer no longer need to accept significant deformities in order to preserve their breasts. This oncoplastic concept applies the principles of surgical oncology with those of plastic surgery, which in this chapter will be focused on those women undergoing breast conservation therapy (BCT). Werner Audretsch is credited for his pioneering work in the field of oncoplastic breast surgery, an approach that was initially more popular in Europe and the United Kingdom but has recently gained acceptance and popularity worldwide (1). The oncoplastic terminology will be used in this chapter as it applies to the immediate reconstruction of the partial mastectomy defect. This field has clearly been driven by both patient demands and the development of combined surgical techniques made possible through greater interaction between specialties.

Understanding the Defect

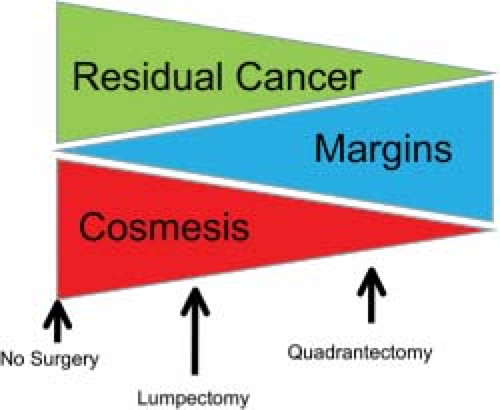

The primary goals of BCT are to adequately treat the breast cancer and minimize local recurrence while preserving breast shape and symmetry. However, there remains an innate conflict between the goals of oncology and cosmesis, with the former being to eliminate all locoregional disease and the latter relying on preservation of as much breast tissue as possible for optimal aesthetic outcome. The wider the margin of resection, the lower is the risk of local recurrence (2,3), and it often becomes a dilemma for the surgeon to meet both these endpoints (Fig. 12.1). Up to 30% of women will have a residual deformity that may require surgical correction (4). There are numerous factors that contribute to poor cosmetic results following BCT. They essentially are related to (a) the amount of tissue resected in relation to the breast tissue preserved and (b) the deleterious long-term effects of radiation therapy.

Factors contributing to poor cosmesis after BCT include the following:

Resection of >15% to 20% breast parenchyma in small breasts and >30% in large breasts

Tumors located in aesthetically sensitive areas: central, medial, inferior

Defect involving skin retracting down to the underlying chest wall

Nipple-areolar malposition

Breast size and degree of ptosis

Higher body mass index (BMI)

Need for reexcision for margin control

Radiation therapy

Traditionally, women with large breasts have been deemed poor candidates for breast conservation surgery because of reduced effectiveness, increased complications, and worse cosmetic outcome. The postradiation sequela in women with macromastia is significantly worse, leading to poor long-term symmetry. Radiation-induced fibrosis is thought to be greater in women with larger breasts, given the dosing inhomogeneity (5,6). Late-radiation fibrosis occurs 36% of the time in patients with larger breasts, compared to 3.6% for patients with smaller breasts. Higher doses of radiation therapy are often necessary in women with larger breasts, contributing to morbidity and adversely affecting the appearance. The cosmetic results following breast-conserving therapy in women with large breasts are also reduced. Clark et al. showed excellent results in 100% of women with A cup breasts following BCT, compared to 50% in women with D cup breasts (7). Women with central or lower quadrant tumors have also been shown to have a worse cosmetic outcome because of tumor location, especially when a significant amount of skin is removed as well. Lower quadrant tumors give twice as poor cosmetic results as lumpectomies in other quadrants. Central breast tumors close to the areolar have in the past been a contraindication to BCT. The tumor-to-breast ratio is one of the most important factors when predicting the potential for a poor outcome. In general, when more than 20% of the breast is excised with partial mastectomy, the cosmetic result is likely to be unfavorable. Younger patient age and elevated BMI have also been shown to be predictors of asymmetry after BCT (8).

Classifying the Partial Mastectomy Defect

Numerous classifications systems have been developed for the late BCT deformity in terms of types 1 to 3 with increasing amount of distortion (4,9,10) and have been used to determined reconstructive options. The data are limited when it comes to describing partial mastectomy defects. We recently expanded on some of the BCT classifications in an attempt to objectively describe the defect at the time of resection and the

various reconstructive techniques that might prevent the deformity (11) (Table 12.1). An important part of any classification system will be the extent of the defect, how much skin is removed, how much tissue is left behind, and where it is in relation to the nipple-areolar complex.

various reconstructive techniques that might prevent the deformity (11) (Table 12.1). An important part of any classification system will be the extent of the defect, how much skin is removed, how much tissue is left behind, and where it is in relation to the nipple-areolar complex.

Preventing the Partial Mastectomy Defect

Although the adverse effects of radiation therapy are often unavoidable, there are principles that can be applied to the resection with or without reconstructive techniques that can be used to minimize the incidence of poor cosmetic results. The oncoplastic approach applies the principles of plastic surgery to the resection as well. A deformity can often be avoided by correctly orienting the breast incisions and parenchymal resection. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy will also downsize the tumor and reduce the required amount of parenchyma resection. Limiting the volume of resection will minimize the incidence of poor cosmetic results. Attention to simple defect closure, including breast advancement flaps and full-thickness closures, is now commonly given by most breast surgeons, and these are ways to improve results. The more complex defects with potential for poor cosmesis will often benefit from partial breast reconstruction.

Table 12.1 Classification of the Partial Mastectomy Defect With Potential Outcome and Treatment Options | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Indications for Partial Breast Reconstruction

The two main reasons to reconstruct partial mastectomy defects are to (a) increase the indications for BCT, making breast conservation practical in patients who otherwise might require a mastectomy, and (b) to minimize the potential for a poor aesthetic result (Table 12.2). The decision is typically based on tumor characteristics and breast shape and size.

Based on these factors contributing to a poor aesthetic outcome, the oncoplastic approach is indicated whenever the potential for a poor cosmetic result exists or patients have tumors in whom a standard lumpectomy would lead to breast deformity or gross asymmetry. In particular, this includes women with large tumors, large breasts, lower quadrant tumors, central mound tumors, or a high expected tumor-to-breast ratio. Factors in addition to cosmetic reasons as an indication for this approach include oncologic issues. Important indications include situations where the surgeon is concerned about the potential for negative margins with standard resection and, based on initial pathology or breast imaging studies, needs to perform a wider excision in order for the patient to be a candidate for breast-conserving surgery. The oncoplastic approach broadens the indications for BCT, as these patients might otherwise

have required a mastectomy, the reconstruction of which (i.e., macromastia) often being more challenging with less favorable cosmetic results. Additional indications include women who desire breast conservation despite potential adverse conditions, as well as older women with large, ptotic breasts in whom mastectomy and reconstruction would be difficult.

have required a mastectomy, the reconstruction of which (i.e., macromastia) often being more challenging with less favorable cosmetic results. Additional indications include women who desire breast conservation despite potential adverse conditions, as well as older women with large, ptotic breasts in whom mastectomy and reconstruction would be difficult.

Table 12.2 Indications for Immediate Partial Mastectomy Reconstruction | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

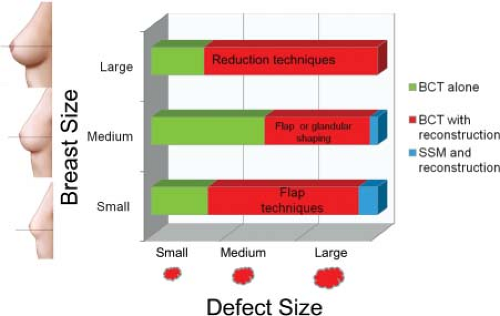

Classification of the Reconstructive Techniques

Partial breast reconstruction uses many of the same familiar principles and techniques used for total breast reconstruction following mastectomy. However, additional techniques have been described that are useful following breast preservation, using the remaining breast tissue and local tissue to repair partial defects. In general, reconstructive techniques involve either using breast tissue to reshape the breast or using flaps as volume replacement (Fig. 12.2). The form of partial reconstruction using residual breast tissue has been referred to as volume displacement, parenchymal remodeling, or simply breast reshaping. These techniques range in complexity from simple advancement flaps (12) to simple glandular flaps to mastopexy and reduction techniques (13,14,15,16). When insufficient breast tissue remains following partial resection, tissue is recruited from outside the breast mound using flap techniques. When flaps are required to reconstruct the partial mastectomy defect, this has been referred to as volume replacement of flap reconstruction. These also range in complexity from local rotational flaps from the axilla, lateral chest wall, and abdomen, to local myocutaneous flaps, to free flaps and perforator flaps (17,18,19,20,21).

Treatment Algorithm

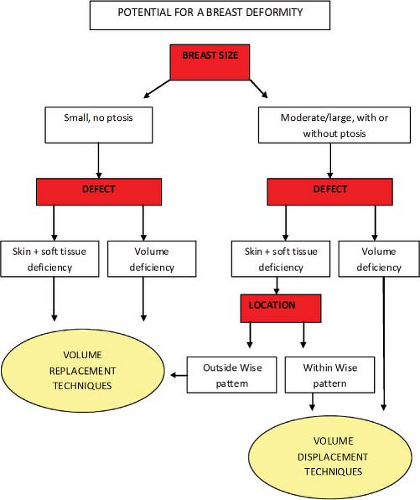

Different algorithms have been described in an attempt to simplify the reconstructive process. There is unfortunately a lack of standardization when it comes to partial breast reconstruction, which makes comparative studies difficult. The decision as to which procedure is more appropriate is multifactorial; however, it is ultimately determined by breast size, tumor size, and tumor location (Fig. 12.3). Other factors are also important, including patient risks and desires, tumor biology, and surgeon comfort level with the various techniques. Another way of looking at this is to evaluate the amount of breast tissue that remains following completion of the partial mastectomy and where that tissue is in relation to the nipple-areolar complex since this will dictate the most appropriate reconstruction option for that particular case. Not unlike the reconstruction of Moh’s defects, these oncoplastic reconstructions can be both challenging and rewarding. Adhering to strict algorithms is difficult since every case is different. Being familiar with the various reconstructive tools will allow reconstruction of almost any partial mastectomy defect. It is important to keep in mind that when the defect is extensive with little remaining breast tissue, completion mastectomy and immediate reconstruction is often the more appropriate option.

Some simple rules of thumb exist for reconstructing partial mastectomy defects. Large or moderate-sized breasts or ptotic breasts with sufficient parenchyma remaining following resection are amenable to volume displacement or reshaping procedures (Fig. 12.4). Quadrantectomy-type resections are possible when they are within the standard Wise pattern markings. In smaller or nonptotic breasts, when additional volume is required to match the opposite breast or when skin is required to replace a resection that included parenchyma and skin, volume

replacement procedures, including volume and skin, are required (Fig. 12.5). Quadrantectomy-type resections in small breasts and in the upper or outer quadrant invariably require a flap reconstruction to preserve shape. See Table 12.3.

replacement procedures, including volume and skin, are required (Fig. 12.5). Quadrantectomy-type resections in small breasts and in the upper or outer quadrant invariably require a flap reconstruction to preserve shape. See Table 12.3.

Volume Displacement Techniques

The breast-reshaping procedures all essentially rely on advancement, rotation, or transposition of a large area of breast to fill a small or moderate-sized defect. This absorbs the volume loss over a larger area. In its simplest form, it entails mobilizing the breastplate from the area immediately around the defect in a breast flap advancement technique (12). The dissection is over the pectoralis muscle and essentially involves a full-thickness segment of breast fibroglandular tissue advanced to fill the dead space. These procedures are indicated in the type 1 deformities for small to medium-sized breasts where the resection does not lead to any significant volume alteration that might cause breast asymmetry. A contralateral symmetry procedure is typically not required.

Table 12.3 Partial Mastectomy Reconstruction Techniques | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

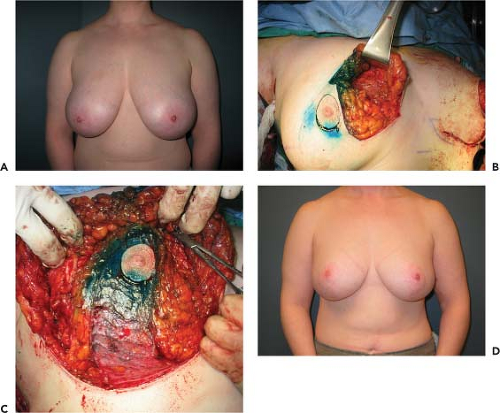

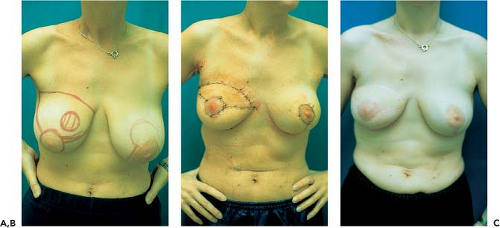

Perhaps the most popular and versatile breast-reshaping options are the mastopexy or reduction techniques. The ideal patient is one in whom the tumor can be excised within the expected breast reduction specimen in medium to large or ptotic breasts where sufficient breast parenchyma remains following resection to reshape the mound (type 2b defects) (Fig. 12.6). Masetti et al. described a four-step design for oncoplastic operations: (a) planning skin incisions and parenchymal excisions following reduction/mastopexy templates, (b) providing parenchymal reshaping following excision, (c) repositioning the nipple, and (d) correcting the contralateral breast for symmetry (14). Any moderate to large breast can be reconstructed using these techniques unless a skin deformity exists beyond the standard Wise pattern (type 2a defect).

Plastic surgeons are familiar with these techniques, making the incorporation of this approach into their reconstructive practice an easy addition. There has been an exponential increase in reports over the last few years describing these techniques showing generous resections, acceptable morbidity, and good outcomes. In women with large or ptotic breasts, the numerous reduction patterns or pedicle designs will invariably allow remodeling of a defect in any location and any size, as long as sufficient breast tissue and skin is available. Creative mammaplasty designs can be made for complete removal of the lesion and reshaping of the mound for both lumpectomy- and quadrantectomy-type defects (Figs. 12.7 and 12.8). Preoperative markings are important, and a decision is made on pedicle design depending on tumor location. Typically, if the pedicle

points to or can be rotated into the defect, it can be used. The Wise pattern markings are more versatile, allowing tumor resection in any breast quadrant. Once the resection is performed, the cavity is inspected, paying attention to the defect location in relation to the nipple, as well as the remaining breast tissue. The reconstructive goals include (a) preservation of nipple viability, (b) reshaping of breast mound, and (c) closure of dead space. The nipple and dermatoglandular pedicle is dissected, and remaining tissue is resected if necessary for completion of the reduction. Occasionally, additional dermatoglandular or glandular pedicles can be created from tissue that might otherwise have been resected, and they can be rotated to autoaugment the defect (Fig. 12.9). The contralateral procedure is performed using a similar technique. The ipsilateral side is typically kept about 10% larger to allow for radiation fibrosis. Additional tissue sampling from the ipsilateral or contralateral breast is also possible using this technique (Fig. 12.10).

points to or can be rotated into the defect, it can be used. The Wise pattern markings are more versatile, allowing tumor resection in any breast quadrant. Once the resection is performed, the cavity is inspected, paying attention to the defect location in relation to the nipple, as well as the remaining breast tissue. The reconstructive goals include (a) preservation of nipple viability, (b) reshaping of breast mound, and (c) closure of dead space. The nipple and dermatoglandular pedicle is dissected, and remaining tissue is resected if necessary for completion of the reduction. Occasionally, additional dermatoglandular or glandular pedicles can be created from tissue that might otherwise have been resected, and they can be rotated to autoaugment the defect (Fig. 12.9). The contralateral procedure is performed using a similar technique. The ipsilateral side is typically kept about 10% larger to allow for radiation fibrosis. Additional tissue sampling from the ipsilateral or contralateral breast is also possible using this technique (Fig. 12.10).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree