14 Reconstruction of acquired vaginal defects

Synopsis

Acquired vaginal defects are most commonly the result of oncologic resections.

Acquired vaginal defects are most commonly the result of oncologic resections.

Current approaches to reconstruction of these defects most commonly involves local or regional flaps if primary closure is not an option.

Current approaches to reconstruction of these defects most commonly involves local or regional flaps if primary closure is not an option.

Flap selection based on defect type is described (Table 14.1).

Flap selection based on defect type is described (Table 14.1).

A cautious approach to postoperative management, as well as careful adjustment of patient expectations, is critical in the care of these patients.

A cautious approach to postoperative management, as well as careful adjustment of patient expectations, is critical in the care of these patients.

Table 14.1 Previously described flap options for vaginal reconstruction

| Defect type | Flap option |

|---|---|

| IA | Singapore flaps (aka pudendal fasciocutaneous flap) |

| IB | Pedicled rectus myocutaneous flap |

| Pedicled rectus musculoperitoneal flap | |

| Muscle-sparing rectus myocutaneous flap | |

| IIA/B | Vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous |

| Gracilis | |

| Singapore flaps | |

| Pedicled jejunum | |

| Sigmoid colon |

Historical perspective

APRs are performed for very low rectal tumors. In this procedure, the entire rectum, anal canal, and anus are removed, and a permanent colostomy is created. Perineal wound complications such as delayed healing and infection are common in these patients, especially those who have undergone irradiation. Major wound complications have been reported in 14–41% of patients following APR when defects have been closed primarily.1 When APR was first described in 1908, the perineal wound was left open and allowed to heal by secondary intention.2 This approach led to serious morbidity associated with delayed wound healing, and was subsequently replaced by primary closure with suction drains and then delayed reconstruction. This approach was also problematic, especially for irradiated wounds as the wounds broke down commonly and delayed reconstruction was difficult. Today, immediate local or regional flaps are the most common approach to managing these large APR defects.

When pelvic exenteration was first performed in the 1940s, the operative mortality was greater than 20%.3 Today, perioperative mortality is 3–5%.4,5 The historical approach to these defects is similar to that of the APR defect: wounds left open to heal by secondary intention, or primary closure over drains with delayed reconstruction if the wound broke down. Today, many pelvic exenteration defects are immediately reconstructed using flaps. Despite the change in approach to these defects, there remains significant morbidity in more than 50% of patients.4 Even with immediate flap reconstruction to improve vascularity and to decrease dead space, infection may occur in 9–11%, and delayed wound healing in up to 46%. Other significant complications include intestinal adhesions, fistulas, and pelvic herniation.6

Basic science/anatomy

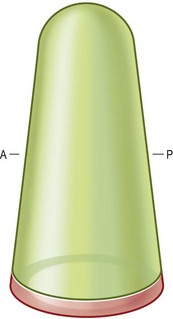

The vagina is essentially a distensible cylindrical pouch (Fig. 14.1). Normal length is 6–7.5 cm along its anterior wall and 9 cm along the posterior wall.7 It is constricted at the introitus, dilated in the middle, and narrowed near its uterine extremity. In its normal anatomic position, the vagina tilts posteriorly as it extends up into the pelvis, forming a 90° angle with the uterus. Careful orientation of the neovagina is important to successful reconstruction and ultimate sexual function. The introitus is a frequent site of contracture after reconstruction, and any distortion of its normal position relative to other structures such as the urethral orifice, perineal body, and anus should be addressed. If no resection of the external vulva and perineum is required, great care must be taken to avoid their distortion because this may also have an impact on sexual function and body image.

Diagnosis

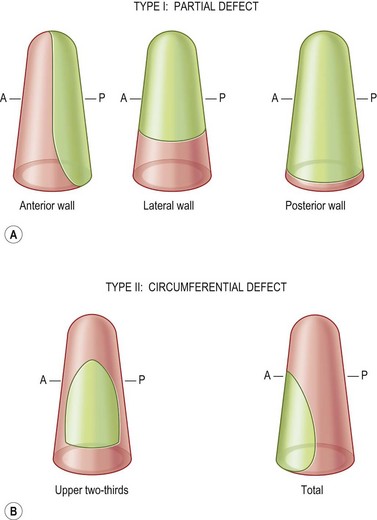

The classification of acquired vaginal defects is based on their anatomic location (Fig. 14.2). This classification will help to guide reconstructive efforts. There are two basic types of vaginal defect: partial (type I), and circumferential (type II). These basic types can be further subclassified. Type IA defects are partial, and involve the anterior or lateral wall. These defects may result from the resection of urinary tract malignant neoplasms or primary malignant neoplasms of the vaginal wall. Type IB defects are partial, and involve the posterior wall. These defects, which tend to be the most common type of vaginal defect requiring reconstruction, result primarily from extension of colorectal carcinomas. Type IIA defects are circumferential defects involving the upper two-thirds of the vagina. These defects are typically the result of uterine and cervical diseases. Type IIB defects are circumferential, total vaginal defects that are commonly the result of pelvic exenteration. These defects result in considerable soft-tissue loss, dead space, as well as distortion of the introitus.

Patient selection

Most important to the success of the reconstruction is the full and informed involvement of the patient and her family. It is important to be specific about the goals of vaginal reconstruction with patients, which include effective wound healing and restoration of body image and sexual function8 (Box 14.1). For those women motivated to preserve sexual function, a comprehensive program of sexual rehabilitation may be warranted. Ratliff et al. investigated sexual adjustment after vaginal reconstruction with gracilis myocutaneous flaps and found that, although 70% of patients were judged to have a physically adequate vagina, fewer than 50% resumed sexual activity.9 Absence of pleasure (37%), problems with vaginal dryness (32%), excess secretions (27%), self-consciousness about ostomies (40%), and self-consciousness about nudity in front of their partner (30%) were the most considerable concerns. Preoperative and postoperative counseling, in addition to postoperative rehabilitation strategies (vaginal dilators, lubricants, topical estrogens), have been suggested as the best way to influence these outcomes positively and give patients the best hope of functional and psychological recovery.8,10 The psychologist and sex therapist should be an integral part of the ablative-reconstructive team. In addition, at most tertiary care institutions, specialized nursing teams can help the patient and her family prepare for the psychological distress that they may experience.

Box 14.1

The major goals of vaginal reconstruction

Treatment/surgical technique

There are five basic goals in vaginal reconstruction (Box 14.1). Selection of the optimal reconstructive method to achieve these goals is based on the type of defect and the characteristics of the patient. Small defects that can be closed without tension will ideally be closed primarily. In the case of the irradiated wound, however, one must proceed cautiously with primary closure. Rarely is skin grafting alone an adequate alternative in oncology patients.

Proceeding along the reconstructive ladder, regional flaps continue to be the most frequently used and effective procedures. Many flaps have been described, none of which is ideal for all defect types (Table 14.1).11–17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree