Radial Forearm Free Osteocutaneous Flaps for Intraoral Reconstruction

J. B. BOYD

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This is an excellent description of the harvesting of bone with the radial forearm flap. The bone is quite useful for short defects of up to 10 cm in a straight line. The procedure is not intended for use around the mentum, where a curving bone is needed. Postoperatively, the forearm requires splinting for at least 6weeks to decrease the incidence of radial bone fractures.

The radial forearm osteocutaneous flap, basically a fasciocutaneous flap based on the radial artery, is thin, supple, and easy to elevate. It has large vessels, a long pedicle, and a capacity to be sensate or to carry a bone supply (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). It also has the advantage of allowing simultaneous dissection in two-team head and neck surgery. This flap is especially useful for low-volume, short (2-10 cm) mandibular defects.

INDICATIONS

The capacity of the forearm flap to carry two separate skin paddles allows it to reconstruct full-thickness defects (6) with an ease not matched by the fibula or iliac crest (7). It also provides mucosal replacement second to none. The skin flap is thin, supple, and, with reinnervation, capable of sensation approaching

that in the normal mouth, which enhances oral continence and may improve speech, mastication, and swallowing (4).

that in the normal mouth, which enhances oral continence and may improve speech, mastication, and swallowing (4).

The segmental supply of the radial bone by the artery allows it to be osteotomized once or twice for accurate contouring in the symphysial and parasymphysial regions. A lateral segment of mandible may be handled as a “straight shot,” using the radial bone as a biocompatible reconstruction plate.

ANATOMY

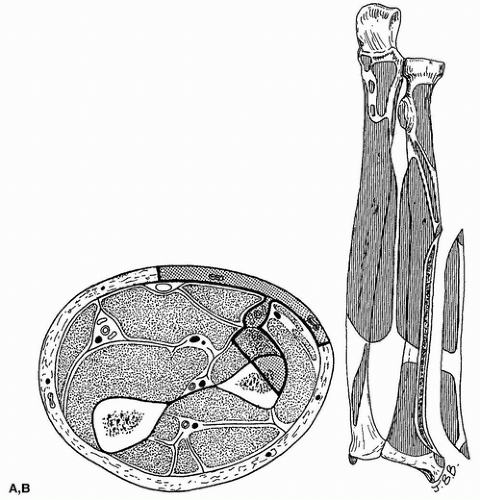

The bone carried by this flap is approximately one third of the cross-sectional area of the distal anterolateral radius (Fig. 204.1). Although small, the bone is quite strong and will accept osseointegrated implants for dental rehabilitation (8).

The skin of the anterior forearm receives a significant blood supply from the radial artery via septocutaneous vessels passing along the septum between the brachioradialis and the flexor carpi radialis muscles (the lateral intermuscular septum). These perforators are plentiful in the distal third of the forearm, but proximally, where tendons give way to muscle bellies, they become rather sparse. Nevertheless, it is probably safe to raise a septum-based skin flap anywhere along the course of the radial artery. In this way, two skin islands may be raised, one proximal and one distal, to facilitate reconstruction of the through-and-through defect.

After emerging from the septum, the vessels branch laterally and medially, piercing the deep fascia and quickly passing to the subdermal plexus to supply the skin. Contrary to previous teachings, these vessels do not travel on the surface of the deep fascia for any significant distance; as a result, little of the deep fascia needs to be harvested with the flap.

The brachial artery bifurcates into radial and ulnar arteries a few centimeters distal to the antecubital fossa. The radial artery and its venae comitantes are invested by the fascia of the lateral intermuscular septum. The artery passes distally along the radial side of the pronator teres, initially lying between the biceps tendon and the bicipital aponeurosis. It then crosses anterior to the pronator teres, just proximal to that muscle’s insertion into its tubercle on the lateral surface of the radius. On entering the distal third of the forearm, it first overlies the flexor pollicis longus and finally the pronator quadratus. These two muscles intimately clothe the flat anterior surface of the distal radius (Fig. 204.1). Muscular branches from the radial artery give periosteal twigs to the underlying bone and are the basis for the osseous portion of the flap.

Classically, there are three major subcutaneous veins in the anterior forearm: the cephalic, the median, and the basilic. There are significant variations on this basic pattern. Perforating veins connect the superficial veins to the deep system at various points. Of most interest here is the communication at the level of the brachial artery bifurcation, which may be single or multiple and may be from any of the superficial veins (commonly the median).

Either the venae comitantes or the large subcutaneous veins of the forearm are capable of draining the osteocutaneous forearm flap. The superficial veins are often preferred because of their greater diameter and their independence from

the arterial pedicle. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that the superficial veins have not been canalized previously and undergone partial or complete thrombosis.

the arterial pedicle. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that the superficial veins have not been canalized previously and undergone partial or complete thrombosis.

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (C8, T1) enters the forearm in the company of the basilic vein. It soon gives off a number of large anterior branches that pass down the radial side of the basilic vein and supply the ulnar half of the anterior forearm as far as the wrist. An ulnar branch supplies the ulnar border of the forearm. The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve (C5, C6) is the forearm continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve. It enters the forearm on the ulnar side of the cephalic vein and, via multiple branches, supplies the radial half of the forearm as far as the wrist as well as the dorsoradial aspect of the forearm.

FLAP DESIGN AND DIMENSIONS

It is useful to mark the radial artery and the larger subcutaneous veins on the skin surface. The skin flap is usually positioned over the anterior or anterolateral aspect of the distal wrist. Here the subcutaneous tissue is thinnest, the skin is reasonably hairless, and the pedicle length is maximized. The relationship of the skin flap to the bone graft should be assessed carefully in view of the expected recipient defect. The bone graft will extend proximally for up to 12 cm from a point 2 cm proximal to the tip of the styloid process (see Fig. 204.1). Usually, the recipient defect requires the skin paddle to lie over the midpoint of the bone, but this is not always the case. It is advantageous to position the flap anterolaterally in such a way that part of it overlies the cephalic vein. This vessel can be used for venous drainage. In hirsute patients, the flap may be positioned purely on the anterior aspect of the distal wrist where the skin is less hairy for a superior cosmetic result. Unfortunately, the median vein is often quite small in the distal wrist. If an innervated flap is required, it should be noted that the watershed between the neurosomes of the lateral and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves lies down the midline of the anterior forearm. Those positioned centrally, and straddling two neurosomes, require both superficial nerves (4).

The flap may be of almost any dimensions as long as a significant portion of it overlies the vascular septum. Practically, the whole anterior forearm skin may be taken safely, but this is rarely required. Limits extend from the antecubital fossa to the transverse wrist crease and from the ulnar border of the forearm to the posterolateral aspect of the radial border. Raising a flap of such dimensions would require the entire vascular septum to be preserved. The “base” of any radial forearm skin flap is that portion in direct contact with the vascular septum. Like any flap, if the base is small, the surviving length is accordingly reduced.

When small skin islands are required (less than 6 × 4 cm), it is sometimes possible to perform primary closure at the donor site (9). Such a flap is positioned transversely with one edge overlying the radial artery. Closure is effected by means of a long, ulnar-based rotation-advancement of the entire proximal forearm skin. The proximal defect is closed as a V to Y. Wrist flexion facilitates closure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree