Radial Forearm Cutaneous Flap for Hypopharyngeal Reconstruction

J. B. BOYD

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This flap has significant advantages, in that the blood supply to the flap is quite vigorous. It avoids the intraperitoneal approach; however, the donor disability in the forearm is its biggest drawback.

The radial forearm flap (1) is extremely versatile because of its thin, supple nature; its ease of elevation; its large vessels and long pedicle; and its capacity to be sensate (2, 3, 4). To these advantages must be added the possibility of simultaneous dissection in two-team head and neck surgery and the ease of tubing the flap for pharyngeal reconstruction (5, 6). The donor defect is cosmetic rather than functional, but the patient must endure 2 weeks of immobilization to allow the skin graft to take.

INDICATIONS

The radial forearm flap may be used as a patch for noncircumferential defects, or it may be tubed when a complete section of the hypopharynx has been removed. A patch is indicated when at least one third of the circumference remains following resection of the tumor. If less than a third remains, the remanent may just as well be discarded, for its only contribution would be to impose a second longitudinal suture line on the repair (7).

Many would argue that the radial forearm flap is second choice to free jejunum for circumferential pharyngeal and hypopharyngeal defects. The jejunum, being tubular, requires only superior and inferior enteric anastomoses; the radial forearm flap has a longitudinal seam as well. The potential for leakage and fistula development is correspondingly greater. It should be noted that swallowing is often quite slow with a jejunal graft, even though peristalsis is orthodromic (8). The tubed radial flap, although only a passive conduit, seems to offer less delay. Furthermore, there are circumstances in which the radial forearm flap might be preferred over enteric substitutes. For example, multiple previous abdominal surgeries or active Crohn disease would make the necessary laparotomy excessively risky.

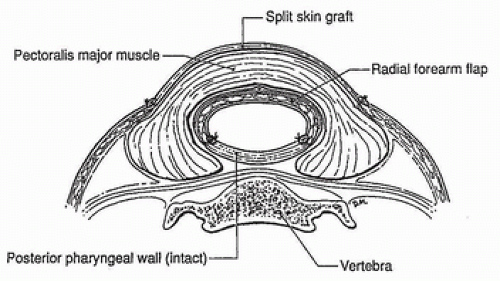

When a patch repair is required, however, the jejunum has no advantages over the forearm. In fact, the long pedicle of this flap, its capacity for reinnervation, and its more accessible donor site give it the edge. When the larynx is still present, reinnervation may help prevent aspiration (2). Patch repair is indicated following a pharyngectomy or pharyngolaryngectomy when there is insufficient pharyngeal wall for a tension-free closure. The closure of such defects without a patch may lead to dehiscence and a pharyngocutaneous fistula. Such fistulas, when large, are themselves another indication for patch repair using a radial forearm flap. In this case, there is a requirement for a two-layer closure. The radial forearm flap can bear two skin paddles, but it is probably more effective to use a single paddle for the inner layer and to cover the repair with pectoralis muscle (Fig. 229.1), which has the ability to overlap, adhere to, and seal the anastomotic suture line (7).

ANATOMY

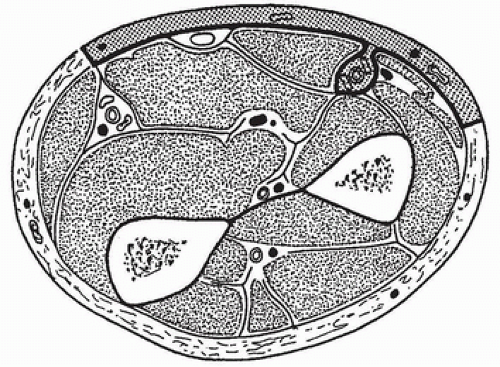

The skin of the anterior forearm receives a significant blood supply from the radial artery via perforating septocutaneous vessels passing to the skin along the vascular septum between the brachioradialis and the flexor carpi radialis muscles (Fig. 229.2). These perforators are plentiful in the distal third

of the forearm; proximally, where tendons give way to muscle bellies, they become sparser. Nevertheless, it is probably safe to raise a septum-based skin flap anywhere along the course of the radial artery. In this way, two skin islands may be raised, one proximal and one distal, thereby facilitating two-layer closure of a large pharyngeal fistula.

of the forearm; proximally, where tendons give way to muscle bellies, they become sparser. Nevertheless, it is probably safe to raise a septum-based skin flap anywhere along the course of the radial artery. In this way, two skin islands may be raised, one proximal and one distal, thereby facilitating two-layer closure of a large pharyngeal fistula.

After emerging from the septum, the vessels branch laterally and medially, piercing the deep fascia and quickly passing to the subdermal plexus to supply the skin. Contrary to previous teaching, these vessels do not travel on the surface of the deep fascia for any significant distance. As a result, little of the deep fascia needs to be harvested with the flap.

Practically the whole anterior forearm skin can be safely taken. Limits extend from the antecubital fossa to the transverse wrist crease, and from the ulnar border of the forearm to the posterolateral aspect of the radial border. Raising a flap of such dimensions would require preservation of the entire vascular septum. The “base” of any radial forearm skin flap is that portion in direct contact with the vascular septum. Like any flap, if the base is small, the surviving length is accordingly reduced. Length-to-width ratios of 2 or more should be avoided.

The brachial artery bifurcates into radial and ulnar arteries a few centimeters distal to the antecubital fossa. The radial artery passes distally along the radial side of the pronator teres, initially lying between the biceps tendon and the bicipital aponeurosis. It crosses anterior to the pronator teres just proximal to that muscle’s insertion into its tubercle on the lateral surface of the radius. On entering the distal third of the forearm, it first overlies the flexor pollicis longus and finally the pronator quadratus. Septocutaneous branches from the radial artery pass along the vascular septum between the brachioradialis and flexor carpi radialis muscles to supply the skin (see Fig. 229.2).

The radial artery is accompanied by two venae comitantes. These vessels are constant but of variable diameter. Often, they are inconveniently small for microvascular anastomosis. In the region of the bifurcation of the brachial artery, there is a confluence of veins. Here, the venae comitantes of both ulnar and radial arteries communicate with each other as well as with one or more of the large subcutaneous veins of the forearm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree