Pyoderma Gangrenosum: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

The prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is unknown. Estimates have suggested that approximately three cases of PG per million of the population occur per year, with most large referral centers seeing one to two cases per year.1 It has been reported in all age groups but mainly affects adults between the ages of 40 and 60 years.2 Most reported series of patients with PG indicate a moderate preponderance of females. PG often occurs in patients who have other diseases (arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic dyscrasias, etc.), but is not a manifestation or complication of these diseases and its clinical course is usually unrelated to their severity or activity.3

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of PG is unknown, and its pathogenesis poorly understood. Based on the presence of a lymphocytic infiltrate at the active advancing border of PG lesions, it has been postulated that lymphocytic antigen activation occurs with cytokine release and neutrophil recruitment. This may take place not only in the skin but also in other tissues such as the lung, intestine, and joints. The predominance of the neutrophilic infiltrate in established lesions of PG have led to its classification as one of the neutrophilic dermatoses.4 Clinical (and to an extent histologic) overlap occurs with the other dermatoses in this category, especially atypical or bullous forms of Sweet syndrome (see Chapter 32). Several of the neutrophilic dermatoses (Sweet syndrome, erythema elevatum diutinum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, and PG) share an association with immunoglobulin A monoclonal gammopathy, and diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and hematologic disorders occur more frequently than expected in these patients. The recent description of the PAPA (Pyogenic Arthritis, Pyoderma gangrenosum-Acne) syndrome,5 a disease considered to be one of the “autoinflammatory” diseases, raises the possibility that PG may lie within this spectrum.

Clinical Findings

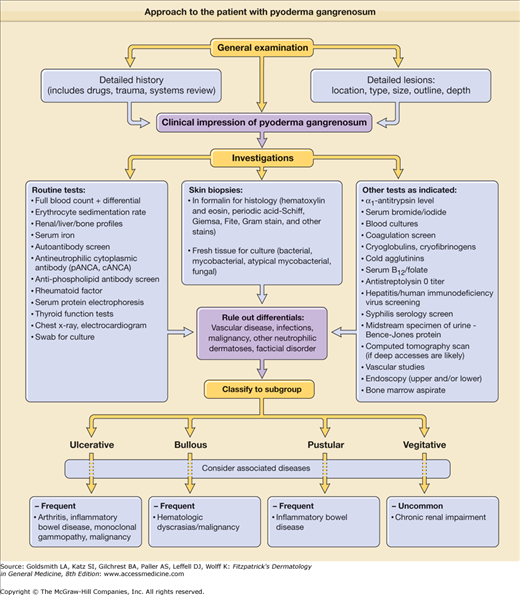

The approach to an individual suspected of having PG is outlined in the patient algorithm (Fig. 33-1). The clinical presentation of PG may be diverse and there is neither a diagnostic laboratory test nor pathognomonic histopathologic findings. Therefore, it is important to avoid misdiagnosing other diseases as PG.6 The most important considerations are the exclusion of infection (bacterial, viral, and deep fungal), vascular disease (stasis, occlusion, and vasculitis), and malignancy in every patient. Close follow-up and reevaluation (with repeated skin biopsies, tissue and swab cultures, and other tests as clinically indicated) is an important part of the ongoing evaluation of patients with suspected PG, particularly those who show a poor response to therapy.

A patient with PG usually complains of severe pain that is out of proportion to the clinical appearance of the lesion. Approximately 25% of patients note the onset of PG at sites of cutaneous trauma (needle stick, inoculation site, insect bites, or surgical procedures). This is called the pathergic phenomenon (Fig. 33-2). Lesions progress rapidly (with the exception of vegetative PG) and cutaneous destruction evolves over days rather than weeks. Special inquiry regarding drug intake (especially iodides/bromides, hydroxyurea); exposure to and symptoms of infectious diseases (Box 33-1); symptoms relating to the musculoskeletal system (joint pains, swelling, etc.), the gastrointestinal tract (abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, etc.), hematologic disease (tiredness, anemia, bruising, blood clotting disorders, etc.), respiratory disease, and nonspecific but potential malignancy-related symptoms, such as weight loss and fatigue, should be made.

VARIANT SPECIFIC |

|---|

Ulcerative PG |

Most Likely |

Vascular |

Venous stasis ulceration |

Occlusive disease/Arteritis |

Vasculitis |

Antiphospholipid–antibody syndrome |

Malignancy |

Primary or secondary |

Infection |

Bacterial |

Mycobacterial/Atypical mycobacterial |

Viral (herpes simplex) |

Deep fungal infection (Sporotrichosis, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus) |

Other |

Drugs (halogenoderma/hydroxyurea, etc.) |

Consider |

Infection |

Necrotizing fasciitis |

Syphilis/Amebiasis/Mucormycosis |

Histoplasmosis/Rhizopus |

Other |

Dermatitis artefacta |

Calciphylaxis/Insect bite (spider) |

Bullous PG |

Most Likely |

Infection |

Bacterial (cellulitis/impetigo) |

Viral (in immunocompromised) |

Fungal (mucormycosis in diabetics) |

Other |

Sweet syndrome/Behçet disease |

Consider |

Bullous dermatoses |

Erythema multiforme/Bullous pemphigoid |

Other |

Insect/Arthropod bite/Malignancy |

Pustular PG |

Most Likely |

Infection |

Bacterial/Viral/Fungal |

Vasculitis |

Pustular vasculitis |

Consider |

Other |

Pustular psoriasis |

Sneddon–Wilkinson disease |

Pustular drug eruption |

Bowel bypass syndrome |

Pyostomatitis vegetans |

Vegetative PG |

Most Likely |

Infection |

Bacterial/Viral/Fungal |

Mycobacterial/Atypical mycobacterial |

Leishmaniasis |

Consider |

Blastomycosis-like pyoderma |

Dermatitis artefacta/Malignancy |

Pyoderma vegetans |

SITE SPECIFICa |

Parastomal |

Most Likely |

Dermatoses (extraintestinal Crohn’s) |

Irritant/Allergic contact dermatitis |

Other (e.g., psoriasis) |

Infection |

Bacterial (Staphylococcus/Streptococcus)/Cellulitis Fungal (Candida) |

Other |

Extraintestinal inflammatory |

Bowel disease |

Malignancy |

In Wounds |

Most Likely |

Infection |

Bacterial/Cellulitis |

Fungal (e.g., mucormycosis) |

Breakdown |

Suture allergy |

Mechanical |

Consider |

Malignancy |

Genital |

Most Likely |

Infection |

Bacterial/Viral infection (herpes simplex virus, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus) |

Tuberculosis/Tuberculide |

Fournier gangrene |

Malignancy |

Squamous cell/Extramammary |

Paget disease |

Consider |

Infection |

Syphilis/Lymphogranuloma |

Venereum/Histoplasmosis |

Leishmaniasis/Granuloma inguinale |

Other |

Dermatitis artefacta |

Behçet disease |

Head and Neck |

Most Likely |

Infection |

Bacterial/Viral/Fungal |

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp |

Malignancy |

Squamous cell carcinoma |

Basal cell carcinoma |

Consider |

Vasculitis |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) |

Malignant pyoderma |

Other |

Dermatitis artefacta |

PG is protean in its clinical expression with variable presentation according to the variant and the stage of disease. Lesions can be classified morphologically as being (1) ulcerative (the commonest and originally described variant), (2) bullous, (3) pustular, or (4) vegetative. Although some patients may show more than one variant (e.g., isolated pustular lesions frequently occur in patients with ulcerative PG), usually one variant of PG dominates the clinical picture and the patient should be classified accordingly.

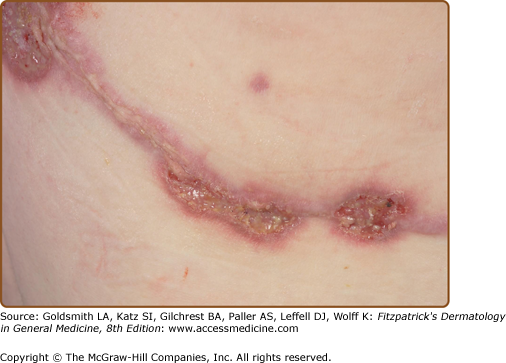

The most common initial clinical lesion in a patient with ulcerative PG is an inflammatory pustule or nodular furuncle (these lesions are usually single but may be multiple). They erupt on apparently normal skin (the most common site being the leg), or sometimes at the site of trauma or surgery (Fig. 33-2). The enlarging initial lesion develops a surrounding areola or zone of erythema that extends into the surrounding skin (Fig. 33-3). As it enlarges, the center degenerates, crusts, and erodes, converting it into an eroding ulcer the development of which is accompanied by an alarming increase in the severity of the pain. The ulcer often has a bluish/violaceous edge (due to undermining by the necrotizing inflammatory process) and the base is covered with purulent material. Ulcerative PG may erode deeply with exposure of muscle or tendon in some cases.