Public Health in Dermatology: Introduction

|

What Is Public Health Medicine All About?

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1 The key message of this definition is that health is a holistic measure that is influenced by socioeconomic factors and inequality. Public health is a discipline in which the level of focus is on the health of populations as opposed to that of individuals, as is the case in clinical medicine. A useful definition of public health is as follows:

Public health is the science and the art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and mental health and efficiency through organized community efforts toward a sanitary environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing service for the early diagnosis and treatment of disease and the development of the social machinery to ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health.2

This definition articulates some of the roles of public health practitioners in relation to society and health. It also highlights the four key areas of public health action: (1) preventing disease and promoting health, (2) improving medical care, (3) promoting health-enhancing behavior, and (4) modifying the environment.3

Historical Perspectives

As early as in the fifth century bc, Hippocrates suggested a clear link between environmental factors and disease states. In more recent centuries, the physician John Snow helped to establish the field of public health during the 1854 London cholera epidemic.4 By carefully counting the number of deaths from cholera according to population denominators in specific London districts, he was able to establish that household water supply might be the key common factor leading to cholera deaths. Snow hypothesized that cholera was a water-borne disease, and he was able to trace the origin of the epidemic to a contaminated water pump in Broad Street, Soho. Consequently, he ordered removal of the pump handle, which was followed by a dramatic reduction in cholera deaths. Thus, Snow first made detailed planned observations, then analyzed the data, formulated a hypothesis, tested this hypothesis through experiment, and finally mounted a campaign to prevent further disease. This led to a widespread political campaigning for clean water from which millions have benefited worldwide ever since. What is intriguing about Snow’s work on the causal relationship between water and cholera is that it preceded the discovery of the Vibrio cholerae organism by Koch a third of a century later.

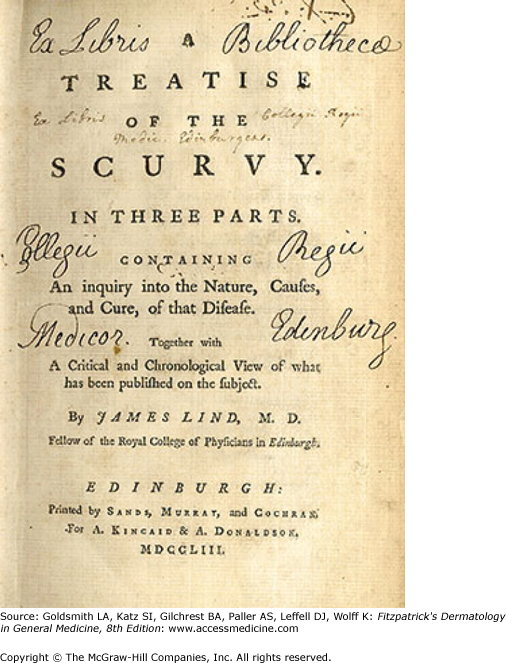

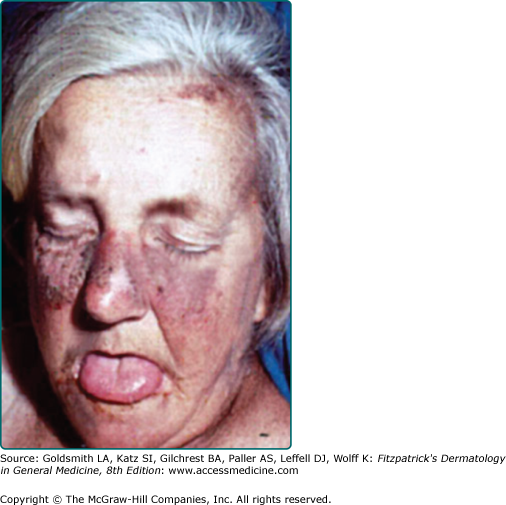

Public health has played a key role in the prevention and treatment of dermatologic diseases. One of the first historical examples is scurvy. In 1746, James Lind discovered through observation, analysis, and performance of a controlled trial that scurvy in sailors was a dietary disease that could be cured by administration of oranges and lemons5 (see eFigs. 4-0.1 and 4-0.2). Lind’s treatise preceded the discovery of vitamin C by more than a century. In 1775, Percivall Pott was the first to describe an occupationally induced cancer by noting that the mortality from scrotal cancer was 200 times higher in chimney sweeps than in other workers.6 He attributed the excess mortality to tar and soot exposure in combination with poor personal hygiene. The first carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon was not discovered until 1933. In the early twentieth century, pellagra was a major public health problem (see eFig. 4-0.3). There were 100,000 deaths from the disease in a 40-year period and over 3 million sufferers in the United States at that time. In 1914, Dr. Joseph Goldberger noticed that inmates at the Georgia State Sanatorium developed high rates of pellagra whereas the nurses and attendants did not, and concluded that the origin of pellagra was probably a disease caused by a dietary deficiency. He confirmed his hypothesis with controlled clinical trials.7 The deficient dietary factor, niacin, was discovered in 1937.

Collectively, these examples illustrate the importance and potential power of public health in the prevention of disease. These examples also highlight the fact that knowledge of disease pathophysiology (i.e., mechanisms) is not always a prerequisite to determining the cause or risk factors for a disease and the potential for effective public health interventions.

High-Risk and Low-Risk Approaches to Public Health

Traditionally, dermatology, like other branches of specialist medicine, has concentrated on the treatment of those who have fallen ill, those who believe they are ill, or people at high risk of developing disease. For instance, we prescribe topical corticosteroids for those with atopic dermatitis, and we may give advice on sun protection to patients who previously had a malignant melanoma. We may see such melanoma patients on a regular basis in skin cancer follow-up clinics to monitor treatment success and to be able to detect recurrences or new early second melanomas. Doctors and patients alike tend to be highly motivated when such an approach is used. The potential benefits seem obvious, and although there may be adverse effects associated with the prescribed treatment, such as skin thinning with prolonged use of topical corticosteroids, or a scar from excision of a melanoma, many patients will accept such risks, because appropriate treatment leads to a tangible and significant improvement of symptoms and improved quality of life or survival. Such an approach to tackling disease has often been referred to in the literature as the high-risk approach, because it focuses on the treatment and detection of those at high risk of developing disease and those who have already fallen ill.8

In contrast to the high-risk approach, the ultimate aim of public health medicine and public health dermatology is to prevent the development of disease in the first place whenever possible, not only by forestalling it in those identified as being at high risk (e.g., because of a strong family history), but by shifting the entire distribution of a certain exposure in a healthier direction for the whole population (population strategy). Such a low-risk approach can be implemented through large-scale public health education campaigns aimed at fundamentally changing the entire population’s behavior and lifestyle. For example, based on the data of the Framingham study one can extrapolate that a reduction of everybody’s blood pressure by 10 mm Hg would result in an overall reduction in mortality from heart disease of around 30%.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree