Prosthetic Reconstruction in the Radiated Breast

Scott L. Spear

M. Renee Jespersen

Breast reconstruction even in the best of circumstances can be a technically difficult challenge. Whether working with flaps, prostheses, or both, the operations are reconstructive in nature, but the expectations can be those associated with cosmetic procedures.

Our experience at Georgetown University confirms the notion that immediate breast reconstruction is quite compatible with early postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. This positive experience is true as long as the immediate reconstruction is successful and the patient heals promptly to allow the chemotherapy program to start on schedule. Reconstructive procedures, whether prosthetic or autologous, that do not heal within 2 to 3 weeks could delay the onset of chemotherapy. Thus, the need for prompt wound healing after immediate breast reconstruction requires good judgment in selecting the right procedure, good technique in performing the operation, and careful postoperative care to prevent and treat wound-healing problems or infection.

Radiation therapy before, during, or after prosthetic reconstruction adds an additional level of complexity (1,2). Although controversy exists as to whether prosthetic reconstruction is the best way to reconstruct a breast in a radiated field, there is evidence that in selected patients it can be done successfully and result in good patient satisfaction (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15). Several facts about breast reconstruction and radiation are generally accepted. First, radiated reconstructions of whatever technique are generally of poorer quality than nonradiated reconstructions. Radiated reconstructions tend to be tighter, less elastic, and less able to mimic normal tissue whether they are autologous or prosthetic. Second, radiation generally increases the complication rate associated with all reconstructive surgery, regardless of type or site. Third, not all radiation is the same. The dose, location, type, and timing of the radiation substantially affect the local tissue response and the hospitality of those tissues to reconstructive surgery. Fourth, the specific nature of the device or type of flap used may affect the success of the procedure in a radiated environment. Thus, although we know unequivocally that radiation has a deleterious effect on all reconstructive procedures, careful consideration of patient factors, implants, procedures, and timing can mitigate the negative effects.

History

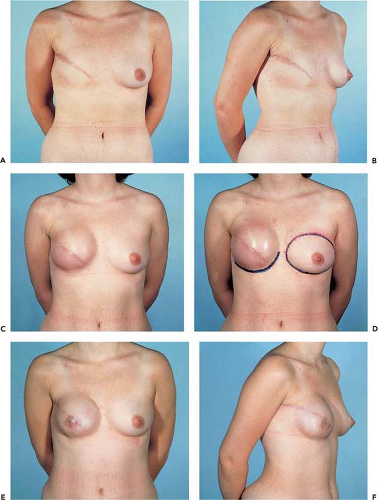

Virtually all reports of implant breast reconstruction in radiated patients include first- and second-generation smooth, silicone gel–filled breast implants exclusively. Such implants were characterized by underfilling of the silicone elastomer envelope, substantial implant mobility, a high degree of implant malleability or ability to be distorted, and a significant risk of capsular contracture. Early versions (pre-1990) of smooth, silicone gel–filled implants, not surprisingly, became firm, distorted, and displaced in nearly all radiated patients. In contrast, post-1992 implants, particularly textured, anatomic breast implants, are designed more for total fill volumes (not underfilling) and minimal mobility. Textured, anatomic gel implants are characterized by limited malleability and generally have a lower incidence of capsular contracture. Our experience so far demonstrates to us that these third-generation and later breast implants seem to fare better than earlier design implants in radiated patients. Similarly, it is our impression that, although their reconstructions are generally firmer than those of nonradiated patients, they may be acceptably soft, reasonably shaped, properly positioned, minimally distorted, and not symptomatically firm or uncomfortable (Figs. 39.1 and 39.2).

Indications

Radiation may be delivered to the breast under a variety of circumstances:

As part of breast conservation treatment, along with a lumpectomy and axillary node biopsy

Postmastectomy, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines for a tumor greater than 4 cm, close to the resection margins, or with four or more positive lymph nodes (11)

Postmastectomy for a local recurrence

Thus, the patient may have been radiated prior to reconstruction or may need to be radiated once reconstruction is underway.

Patients radiated in conjunction with lumpectomy and axillary dissection may receive as little as 5,000 cGy or as much as or more than 10,000 cGy, depending on the nature of their cancer. Patients radiated after a mastectomy are more likely to receive high-dose radiation because the radiation is usually recommended on the basis of extensive or aggressive disease. The patients receiving the lower dose of radiation will often have tissues that look and feel reasonably normal. Patients who have had the larger doses of radiation will typically have tissues that feel tight, inelastic, and thickened (especially early on after radiation therapy).

Patient Selection

In assessing patients for reconstruction in the setting of prior or possible future radiation, it is helpful to consider them in terms of their likelihood to achieve a satisfactory prosthetic result. In patients who have already received radiation, there

are several factors that will predict their ability to tolerate a prosthetic implant. We have identified four that are especially useful.

are several factors that will predict their ability to tolerate a prosthetic implant. We have identified four that are especially useful.

The first is the quality of the radiated skin envelope. If the skin appears to be in good condition after radiation, meaning it is soft, reasonably elastic, and has relatively normal turgor and color, the patient may be a good candidate. If the skin envelope is inelastic, obviously contracted, hardened, and discolored, the patient will likely be better served with a flap-assisted reconstruction (Fig. 39.3).

The second factor is the skin envelope availability. A patient who has a previously radiated breast from breast-conserving therapy presents less of a challenge than a patient who has had a mastectomy with no reconstruction and radiation. Their radiation doses were probably different, but the patient who has no existing breast will have to tolerate significant expansion to obtain a skin envelope large enough to cover an implant. Even if her skin quality is good, radiation will decrease her chances of tolerating expansion. Therefore, patients who have a significant skin envelope deficit will likely be better served with a flap-assisted reconstruction (Figs. 39.3 and 39.4).

The third predictor is a previous prosthetic reconstructive failure. If a patient has an unsatisfactory reconstruction because of severe contracture or has failed attempts at expansion and reconstruction for wound or infectious reasons, the chances of a second attempt being successful are greatly diminished. These patients are better served by a flap-assisted reconstruction (Fig. 39.5).

The fourth factor is patient attitude and expectations. Patients frequently have expectations surrounding breast reconstruction that are more commensurate with cosmetic augmentation. Studies have shown that radiated prosthetic reconstructions are of inferior aesthetic quality to flap reconstructions but that patient satisfaction is still quite high (15). Patients must understand

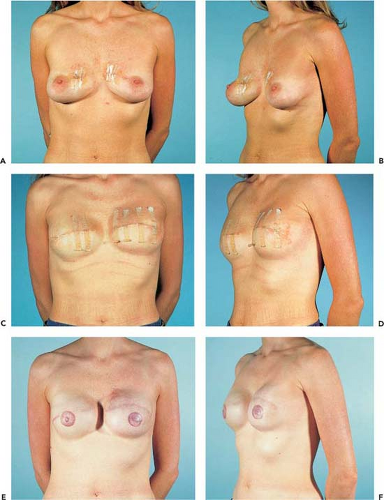

that their reconstruction will not be equivalent to an opposite unradiated breast and that complications and future contracture are a distinct possibility (Figs. 39.6 to 39.9). As long as they understand this aspect of choosing an implant over an autologous reconstruction and that correction of these complications may require use of a flap in addition to their implant, they have a good likelihood of achieving a successful prosthetic reconstruction (Fig. 39.10). In coming to a full understanding of the implications of an implant reconstruction in the setting of radiation, some women opt to incorporate a flap with the implant at the initial reconstruction to decrease chances of complications and the need for further surgery (Figs. 39.11 to 39.16).

that their reconstruction will not be equivalent to an opposite unradiated breast and that complications and future contracture are a distinct possibility (Figs. 39.6 to 39.9). As long as they understand this aspect of choosing an implant over an autologous reconstruction and that correction of these complications may require use of a flap in addition to their implant, they have a good likelihood of achieving a successful prosthetic reconstruction (Fig. 39.10). In coming to a full understanding of the implications of an implant reconstruction in the setting of radiation, some women opt to incorporate a flap with the implant at the initial reconstruction to decrease chances of complications and the need for further surgery (Figs. 39.11 to 39.16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree