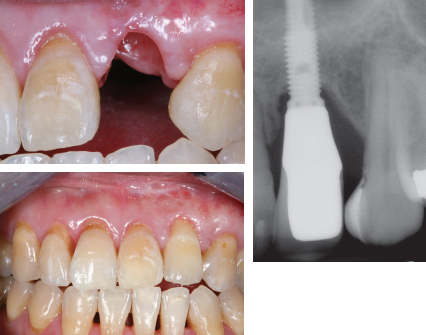

66 ○ Prosthodontic treatment planning should begin as early as possible within a cleft team setting. ○ A patient with a cleft often has significant dental issues that require intensive treatment. ○ The decision to move a canine into the position of a missing lateral incisor is as much a prosthodontic decision as an orthodontic one. ○ Long-term consequences of early treatment decisions should be considered before embarking on a particular dental treatment plan option. ○ Osseointegrated implants provide a high degree of success in replacing missing lateral incisors in properly selected patients. ○ Bone grafting is often required before implant placement for patients with clefts. ○ Many adult patients with clefts still require fabrication of a cleft speech bulb prosthesis. ○ Digital technology may greatly enhance and simplify prosthodontic care for the patient with a cleft. ○ The prosthodontist is an integral member of the cleft treatment team. Restorative dentistry or prosthodontic care for a patient with a cleft palate is often not considered until the patient has reached adulthood or until all the surgical and orthodontic care has been completed. At this point, the patient is referred to the prosthodontist to replace any teeth that are missing or are in need of restorations. Little consideration may have been given to the prosthetic or restorative treatment planning required to provide the optimum overall functional and aesthetic outcome for the patient. The patient with a cleft is best served by having a prosthodontist or restorative dentist become involved as early as possible in the treatment planning process. With the generally accepted principle that the team approach to management of patient with clefts provides the best results, the prosthodontist should become involved in treatment planning at the onset of cleft care, even as early as in infancy. The prosthodontist working with the surgeon, orthodontist, pediatric dentist, and other members of the cleft palate team at the onset of treatment is the most effective model of care. The prosthodontist must not be considered the treatment provider of last resort, to simply manage the unrepaired cleft palate or the failed pharyngeal flap or to merely replace missing teeth once all other phases of care have been completed.1 Several dental conditions are unique to patients with cleft palate. The most common finding in patients with unilateral clefts is the lack of the maxillary lateral incisor on the affected side. Duplication of the lateral incisor is not uncommon, however. Similarly, in patients with bilateral clefts, a second lateral incisor may be present on one or both sides of the maxillary dental arch, located on the premaxillary segment or on the lateral alveolar segments. This duplication of dental units often poses aesthetic challenges in the development of a natural appearance in the patient’s smile. Teeth adjacent to the cleft are often hypoplastic and dysmorphic in form. Prosthetic intervention may be required to provide balance and symmetry in the development of an aesthetic, as well as functional, final tooth arrangement. These teeth may be either larger or smaller than the tooth would normally be in an individual without a cleft. Consideration should be given to the selective extraction of teeth that will not enhance the long-term functional or aesthetic outcome. Therefore the orthodontist and prosthodontist must work closely together in establishing a symmetrical and balanced tooth arrangement while orthodontics are underway, rather than waiting for the “final” tooth position determined solely by the orthodontist. The dysmorphic shape and malposed position of teeth, combined with the increased tendency for mouth breathing, greatly increases the potential for dental caries in this patient population.2 The introduction of fixed or removable orthodontic appliances (or both) increases the potential for plaque accumulation and makes oral hygiene measures more challenging. Patients with clefts have a higher incidence of dental caries. These patients in particular should be thoroughly instructed on the proper methods of daily oral hygiene. Professional dental prophylaxis and examinations should be increased from the usual regimen of twice a year to a minimum of three times per year during the childhood and adolescent years, and perhaps even more frequently while they have fixed orthodontic appliances in place. Early prosthodontic interventions, such as placement of a fixed dental prosthesis to restore badly decayed teeth or to replace missing teeth, must take into consideration the presence of enlarged pulp chambers in the younger patient, thereby making either a carious or mechanical pulpal exposure more likely. Patients and their parents should be advised of the increased risk potential for the need for endodontic therapy for teeth that require extensive restorations. Every attempt should be made to keep tooth preparations for composite restorations, veneers, or crowns as conservative as possible in young patients. An adequate amount of tooth structure should be reduced to provide for physiologic tooth forms in the final restorations. These restorations should not increase the amount of plaque retention or compromise gingival health. In addition to the unique dental conditions that exist in patients with clefts, other important oral factors must be taken into consideration when providing prosthodontic care. A meticulous examination of the hard and soft tissues of the oral cavity, with particular attention paid to the possible presence of small or pinpoint sized fistulae (Fig. 66-1), is necessary. Dental impression material may be trapped in an unrecognized fistula or be pushed into the nasal cavity. The removal of this material may be difficult or impossible without nasal exploration. The presence of an unseen fistula may be discovered by pinching closed the patient’s nostrils and directing the patient to attempt to blow air out through the nose in a Valsalva maneuver. A high-pitched “hissing” sound may be heard or bubbling of mucous or saliva may be seen if a fistula is present. The presence of postoperative palatal scarring tends to produce posterior arch width collapse and the recurrence of a posterior crossbite if retainers are not fabricated and used regularly by the patient who has completed prosthodontic care to replace missing anterior teeth. Although a fixed dental prosthesis may serve to maintain tooth position in the anterior maxilla, unless the prosthesis is large enough and encompasses enough teeth to extend to the maxillary molars, orthodontic relapse, arch-width collapse, and redevelopment of a crossbite are likely. Fig. 66-1 Oronasal fistula at the junction of the primary and secondary palate. At cleft centers that use presurgical infant orthopedics (PSIO), such as nasoalveolar molding (NAM), the management of early infant oral and nasal molding may be undertaken by the orthodontist, prosthodontist, or pediatric dentist on the team, if the practitioner has been trained in the technique.3 The early use of PSIO appliances was initially advocated by a prosthodontist.4 In helping to manage the infant undergoing presurgical orthopedic care, the prosthodontist can become familiar with the development of the patient’s oral structures from the earliest onset of care. Children who have had a successful repair of their cleft have unique factors that should be taken into account as they grow and progress through orthodontic care and eventually into prosthodontic care. After a successful repair of the alveolar cleft, with or without a gingivoperiosteoplasty (GPP), the decision must be made before the eruption of the adult canines as to whether autogenous alveolar bone graft surgery is indicated. This determination is often made at many cleft centers by the orthodontist or surgeon alone, as is the decision to move the adult canine into the position of the missing lateral incisor. These decisions are ideally made in the setting of the cleft team, including the input of the prosthodontist who will ultimately be responsible for restoring, both functionally as well as aesthetically, the teeth in that area. This requires early collaboration between the prosthodontist and the orthodontist to determine the treatment option best suiting each particular child as they progress through their dentofacial development. A variety of orthodontic-prosthodontic pathways may be pursued. At the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at New York University Medical Center, the orthodontic-prosthodontic evaluation usually begins at approximately 8 years old. The determination regarding what is needed to establish a solid and stable posterior occlusion is made while developing a maxillary dental midline that is as closely coincidental with the facial midline as is possible. Consideration will then be given to establishing an intact maxillary alveolus (if this has not already been accomplished through an early GPP after NAM therapy). The positions of the remaining teeth, relative to the available space, are then worked out using a series of diagnostic wax mockups as the child ages and until early adulthood. Often, the decision of whether a missing lateral incisor will best be restored with a transported canine or an osseointegrated implant is not made until the age of 16 years (Fig. 66-2).

Prosthetic Management of Patients With Clefts

Lawrence E. Brecht

KEY POINTS

ORAL AND DENTAL CONDITIONS IN PATIENTS WITH A CLEFT

PROSTHODONTIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR AN INFANT OR CHILD WITH A CLEFT

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine