Principles of Burn Reconstruction

Matthias B. Donelan

Eric C. Liao

Reconstructive surgery following burn injury involves almost every aspect of plastic surgery. The patient population includes children and adults. All areas of the body can be involved. Deep structures can be injured either acutely or secondarily. Satisfactory outcomes require correction of both functional and aesthetic deformities. Yet, at the same time, the reconstruction of burn deformities requires a unique perspective and an emphasis on certain fundamentals and techniques that make it a specialized area of reconstructive surgery. The surgeon must thoroughly understand the processes of wound healing and contraction. The effect of time on the maturation of scars is of pivotal importance and requires patience and judgment on the part of the surgeon and the patient. Correct timing of surgery is essential. Multiple operations are the rule and frequently take place over a period of many years. Donor sites are frequently limited or compromised. Successful surgical outcomes require a well-functioning support system, including nurses, therapists, psychosocial practitioners, and, hopefully, a supportive family. All of these factors affect the outcome of surgery.

Burn injuries vary greatly in severity and extent, yet virtually all postburn deformities have similar components that must be addressed. This chapter provides a strategic approach to burn reconstruction based on surgical principles particularly relevant to this field that will help in the analysis, management, and surgical treatment of this large and challenging group of patients.

GENERAL CONCEPTS

Over the past 50 years, primary excision and grafting of deep second-degree and full-thickness burns has become the standard of care in the United States and in most developed countries (Chapter 16).1,2 Early excision and grafting has decreased the mortality and morbidity of acute burn injuries.3 The duration of acute hospitalization has been greatly reduced. Early excision and grafting has also decreased the frequency and severity of contractures and hypertrophic scarring. Occasionally, however, one still encounters patients who were treated “expectantly” with late grafting and disastrous results (Figure 16.1).

All burns of the second and third degree result in open wounds. Open wounds heal by contraction and epithelialization. Contraction may be decreased by early excision and grafting, but is always present to some degree. Contraction leads to tension, and tension is one of the principal causes of hypertrophic scarring and unfavorable scarring in general. Understanding the role of tension in the evolution of post-burn deformities is essential.

Burn reconstruction is fundamentally about the release of contractures and the correction of contour abnormalities. It should not be focused on the excision of burn scars. Scar excision is an oxymoron. A scar can only be traded for another scar of a different variety. When the fundamental problem is that of inadequate skin and soft tissue, further excision of “scars” can add to the clinical problem. Well-healed burn scars, if given enough time to mature, are often an excellent example of nature’s camouflage. The subtle and gradual transition from unburned skin to scar helps the deformity blend into its surroundings. A burn scar that is conspicuous at 1 year because of hypertrophy, contracture, and erythema can become inconspicuous with further maturation. Healed second-degree burn deformities under tension with resulting hypertrophy are unsightly. With time and relief of tension, they will greatly improve. Premature early excision of such scars with primary closure frequently results in a wide iatrogenic scar, which then becomes a more obvious permanent deformity. Lacking camouflage, the surgical scar may be more noticeable than the burn scar, and increased tension from the excision can create contour deformities. Excision and primary closure of burn scars should be reserved for small scars in conspicuous locations that will allow a favorably oriented closure.

Although counterintuitive, it is helpful to learn to love burn scars. After all, without scarring, healing cannot occur, so scars are our friends. For successful burn reconstruction, one must learn to appreciate scars and understand their behavior. Scar rehabilitation is usually a better alternative for the patient than scar excision. Scars under tension are angry and respond with erythema, hypertrophy, pruritus, pain, and tenderness. Relaxed scars are happy scars. They respond by flattening, softening, and becoming pale and asymptomatic. Directing reconstructive surgery toward relieving tension is practical and achievable and often results in great improvement. Advances in laser therapy have greatly facilitated scar rehabilitation, further decreasing the indications for scar excision. Ill-advised attempts to excise scars can be simplistic and are potentially harmful. Burn reconstruction strives to make the patient clearly better, not just different from normal in a different way.

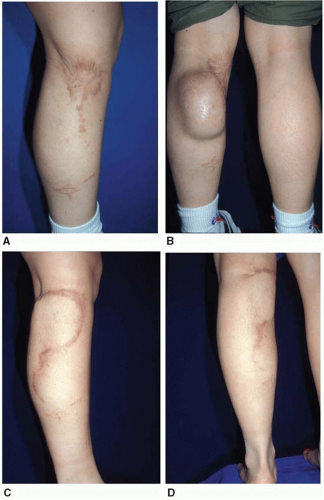

FIGURE 16.1. Contracture due to late grafting. A 4-year-old boy from Central America treated with months of dressings and late grafting, resulting in severe contractures. |

Contracture releases can be accomplished with local tissue rearrangement such as Z-plasties or transposition flaps or by releases and skin grafting of the resulting defects. Releases can be performed by either incising or excising scars. Release by incision takes advantage of the healing that has already occurred and because of the relief of tension, it will usually improve the appearance and quality of the tissue that is retained. Mature scars and grafts are a known commodity and will not contract significantly after release. New grafts are less predictable. Incisional releases also create a smaller defect and, therefore, conserve donor sites. When the contracted tissue is of unacceptable quality, or too irregular, excision of scars is required for the best result (Figure 16.2). In most cases, however, it is better to work with the grafts and scars that are already present than to excise them. Grafts can be either split thickness or full thickness. Defects resulting from scar release can also be closed with flaps transferred with either traditional or microsurgical techniques. The choice of the appropriate intervention and the timing of intervention are both essential ingredients that determine success or failure after burn reconstruction.

TIMING OF RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY

Patients with postburn deformities present to the plastic surgeon in one of three ways. In the ideal circumstance, the plastic surgeon is involved in the patient’s care from the time of the acute injury. The involvement may be as the treating physician or as a consultant with occasional participation in the patient’s acute care. It is a truism that the reconstruction of burn deformities begins with the acute care. Plastic surgical consultation can help prevent secondary deformities by initiating appropriate acute intervention and can also enhance outcomes by assisting with aesthetic decisions such as skin graft donor site conservation. The second group of patients are those with recent burns who received their acute burn care at another facility and come to the plastic surgeon for another opinion. They have immature scars. The third group of patients are those who present with mature scars and grafts and established burn deformities.

The timing of burn reconstruction falls into three distinct phases: acute, intermediate, and late. As a general rule, burn reconstruction is best delayed until all wounds are closed, inflammation has subsided, and scars and grafts are mature and soft. Acute reconstructive intervention is required during the early months following burn injury when urgent procedures are necessary to facilitate patient care, to close complex wounds such as open joints, or to prevent acute contractures from causing irreversible secondary damage. Examples of indications for acute surgical intervention are eyelid contractures with exposure keratitis, cervical contractures causing

airway issues, and “fourth-degree burns,” such as in electrical injuries, where acute flap coverage is required.

airway issues, and “fourth-degree burns,” such as in electrical injuries, where acute flap coverage is required.

The intermediate phase of burn reconstruction is best described as scar manipulation designed to favorably influence the healing process. After a patient’s wounds have closed, physical and occupational therapy must continue to correct or prevent contractures, as well as enhance scar maturation with the use of pressure garments, silicone gels, and massage. The efficacy of such treatments has been demonstrated over many years.4,5 Enthusiastic support of these ancillary measures by the plastic surgeon and the entire burn team can be very helpful in maximizing patient compliance. The length of time required to reach the end point of burn scar maturation is considerably longer than is generally appreciated. Scars that are thick, raised, and erythematous after 1 year or longer will often improve dramatically if given more time, often several years. When tension is present, scars never heal well. Judicious surgical intervention to relieve tension during this intermediate period can positively influence scar maturation. A longitudinal scar across the antecubital space subjected to constant tension and relaxation will remain contracted and hypertrophic despite pressure, silicone, massage, and splinting and may result in ulceration or “spontaneous release.” Relieving tension by either carrying out Z-plasties within the scarred tissue or performing a release and graft can help the entire scar to improve after the tension has been eliminated (Figure 16.3). Hypertrophic scars are common in healed second-degree burns under tension. When the tension is relieved, the subsequent improvement in appearance and elasticity is often remarkable.

Steroids are effective in diminishing and softening hypertrophic scars. Topical steroids are helpful. Steroid injections are powerful. The latter must be used carefully because of potential problems with atrophy of the scar and the underlying subcutaneous tissue.6 Their use should be limited to situations where time, pressure, silicone therapy, and massage are ineffective and surgery is not an option. For example, isolated hypertrophy without tension such as on the face or shoulders is a good indication. A solution of triamcinolone (10 mg/mL mixed half and half with 1% Xylocaine with epinephrine) administered by intralesional injection with a glass tuberculin syringe, never more frequently than once a month, is efficacious in decreasing hypertrophy and preventing undesirable side effects. Ablative fractional laser therapy provides a new, and potentially more efficacious, way of delivering corticosteroids into the dense collagen of hypertrophic scars.

Intermediate-phase scar manipulation is of particular benefit in the management of facial burn deformities. This is an area where treatment is evolving and there is considerable potential for improvement. Computer-generated clear face masks with silicone lining are expensive but efficacious and well tolerated by patients. Relief of tension on facial scars by eliminating extrinsic contractures from the neck, as well as from the inconspicuous periphery of the face by release and grafting or Z-plasties, can be exceedingly beneficial to the healing of facial burns. The pulsed dye laser (PDL) is effective in decreasing facial erythema when used in this intermediate phase and seems to result in more favorable long-term scar maturation. Z-plasties within the hypertrophic scar to

decrease tension and more favorably align scars can achieve dramatic results over time (Figure 16.4).7

decrease tension and more favorably align scars can achieve dramatic results over time (Figure 16.4).7

Late-phase reconstructive surgery includes all postburn deformities that are stable and consist of mature scars and grafts. It is not uncommon in this group of patients for hypertrophic scars to present with areas of open ulceration. This is almost always caused by chronic tension. The resulting ischemia in the scar causes unstable epidermal coverage. Operations directed at relief of the tension will usually cure the chronic open wounds.

The transition from acute burn injury to the late phase of reconstructive surgery can be prolonged and is unique for each patient. The experience, judgment, and expertise of the plastic surgeon are extremely important during this period. After the acute phase of a burn injury, the patients and the patients’ families desire expeditious reconstructive surgery. Patients would like their scars to be “removed” and they want to “get on with their lives.” Most of the time, this is not in the patient’s best interest. As mentioned above, the amount of time that is required for burn scars to reach their final state of maturation is not generally appreciated. If the prolonged process of scar maturation is allowed to occur, particularly when aided by appropriate help from the surgeon and therapists, hypertrophic, contracted, and conspicuous scars that are problematic at 1 year or longer can improve greatly with more time. Because of the gradual and subtle transition from unburned skin to burn scar, mature scars are usually less conspicuous than would be surgical scars resulting from excision and primary closure. Education of the patient and the patient’s family is essential in order to help guide them to the best possible outcome. The desire for “excision” can lead to iatrogenic deformities such as shown in Figure 16.5. This unfortunate result could have been avoided with more time and Z-plasties performed within the maturing hypertrophic scar tissue.

Reconstructive Plan

A prospective plan for reconstructive surgery is developed with the patient and the patient’s family during the intermediate phase or at the time of consultation with a patient who has established postburn deformities. Planning the reconstructive sequence is helpful to the patient, the family, and the surgeon. Because the patient’s priorities may be different from the surgeon’s, education, careful consultation, and mutual agreement are of extreme importance. Operations to improve essential function are the initial priority, but appearance, particularly of the face and hands, is always a consideration. The goal of reconstructive surgery is to return patients as much as possible to their pre-burn condition. Therefore, all reconstructive procedures aim to improve both the function and the appearance of the operated area. The planning process gives the patients perspective and helps them develop a positive attitude as they look forward to significant improvement in the future. Enthusiasm and optimism on the part of the surgeon and the entire reconstructive team is essential. Including the patient’s family in these discussions is important. A strong support system is necessary for what is often a long and arduous process.

Fundamentals

Several basic concepts and techniques are worth reviewing in the context of burn reconstruction.