Each year, 2 million Americans develop nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC), costing health care nearly $500 million. Untreated or incompletely treated tumors lead to disfigurement, nerve damage, functional impairment, and even death. Advanced practice clinicians (APCs) can provide early diagnosis and treatment of NMSC, reducing patient morbidity and mortality. Additionally, APCs can provide valuable preventative education regarding sun safety and early detection of skin cancer through clinical and self-examinations.

PRECANCEROUS LESIONS

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are extremely common lesions which develop in increasing number with cumulative sun exposure and advancing age. Approximately one in five Americans will develop AKs in their lifetime. Patients who develop AKs tend to have fair skin and a history of chronic or intense, intermittent sun exposure, and often have clinical signs of photoaging, including freckles, lentigines, and pigmentary dyschromia. AKs may present years after the sun exposure. These precancerous lesions constitute one of the most common reasons for patients to present to a clinician.

While it is estimated that up to 20% of AKs may develop into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), there is no way to discern clinically if a given lesion will progress. Lesions which become large, thickened, tender, or ulcerated are worrisome for SCC. AKs may resolve spontaneously with sun-protective measures, but persistent lesions are usually treated both for symptomatic relief and to prevent their progression into skin cancer.

Pathophysiology

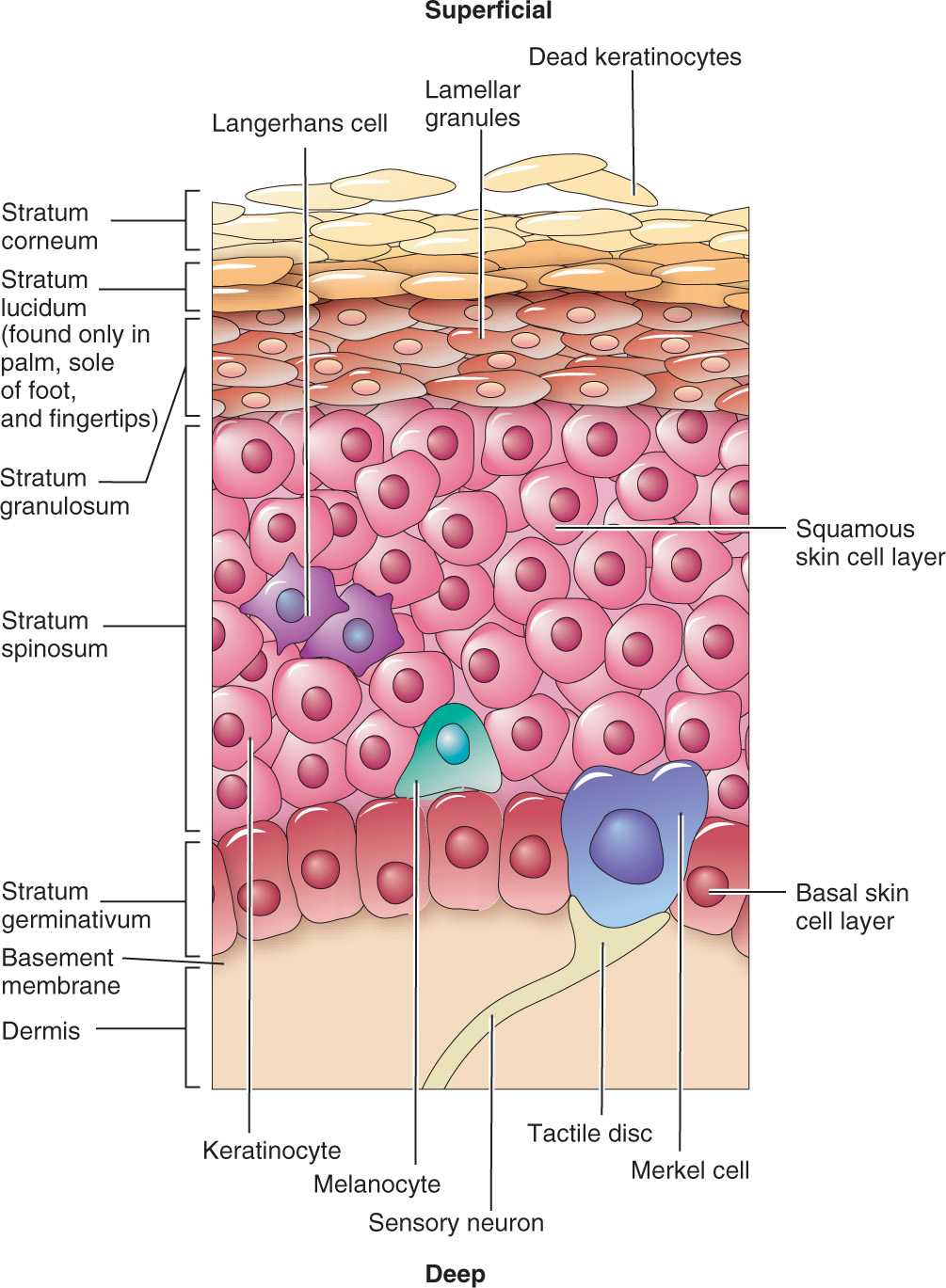

The epidermal layer of the skin is composed of keratinocytes, which slowly migrate from the base to the surface of the epidermis (Figure 8-1). Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) damage to the keratinocytes can result in premalignant transformation. AKs are altered keratinocytes within the epidermis and are thought to represent an intermediary step along the continuum of development to SCC. These atypical keratinocytes show an increased mitotic rate, which have the potential to develop into SCC. If the atypical keratinocytes extend across the full extent of the epidermis, they are designated as localized or in situ SCC.

Clinical Presentation

AKs initially present as a skin color to pink to red, rough areas with a texture likened to that of sandpaper (Figure 8-2). Lesions may develop thick scale, which may evolve into sharp papules or plaques, which may in turn become crusted or bleed when removed. AKs are better detected by feel than by sight; so a tactile examination with the fingertips over sun-exposed areas (i.e., nasal dorsum, helical rims of the ears, and dorsal hands) should be performed.

Discerning an advancing AK from SCC in situ (SCCIS) requires histologic diagnosis made by the dermatopathologist or pathologist. Therefore, AKs with suspicious features, including sensitivity to touch or sun exposure, spontaneous bleeding, size larger than 1 cm, or location adjacent to a previously diagnosed NMSC, warrant a biopsy.

Several variants of AK exist:

Pigmented actinic keratoses (PAKs) are identical to AKs with a brown, blue, or black hue which results from melanocytes within the lesion. PAKs are more often seen in individuals with darker skin tones.

Hypertrophic AKs are lesions which have become very thick, scaly, or crusty plaques. They are often large, yellow, and crusty (Figure 8-3). A biopsy is often needed to exclude SCC.

A cutaneous horn is a hyperkeratotic papule which becomes protruberant (Figure 8-4). Similar lesions may develop from benign seborrheic keratoses or warts; so a biopsy is necessary to identify SCCIS.

Actinic cheilitis is the designation for AKs of the lower lip (Figure 8-5). These lesions are rough, scaly, fissures, or plaques which may be white or hyperpigmented. It is not uncommon for them to become tender, bleed, or ulcerate. Actinic cheilitis persists longer than an HSV lesion and doesn’t resolve with emollients typically helpful for chapped or dry lips.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Actinic keratoses |

• Squamous cell carcinoma

• Lichenoid keratosis

• Basal cell carcinoma

• Psoriasis

• Eczema

• Seborrheic keratosis

• Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis

• Solar lentigo

• Melanoma

• Wart

• Herpes simplex virus

Diagnostics

Lesions which are presumed to be AKs but have not resolved with initial therapy, as well as a cutaneous horn, should also be biopsied. AKs which are becoming larger, thicker, tender, or ulcerated are worrisome for SCC and require histologic evaluation. The shave biopsy is an efficient, well-tolerated procedure that can provide a sufficient tissue sample for histology (described in chapter 24). Yet, if the sample is too shallow and does not include a portion of the dermis, an invasive SCC could be misdiagnosed as an in situ lesion, risking incomplete treatment and recurrence.

Management

There are many treatment options for AKs, including watchful waiting with careful sun-safety measures. Consideration must be given to patient selection, efficacy, risks, side effects, psychosocial variables, cosmesis, compliance, cost, and duration of therapy in selecting the best treatment option for a given patient. Competent primary care providers often provide effective treatment for patients with a few, well-defined AKs using FDA-approved immunotherapy and cryosurgery (Table 8-1). However, off-label treatment with immunotherapy and more advanced procedures should be referred to experienced dermatology specialists to avoid the risk of misdiagnosis, inadequate treatment, and complications.

FIG. 8-1. Anatomy of the epidermis.

FIG. 8-2. AKs on the hand.

Local therapy

When there are a few clearly identified AKs, localized therapy can provide prompt and effective treatment. The knowledge and experience of the clinician providing treatment will impact the patient’s experience and treatment outcomes.

FIG. 8-3. Hypertrophic AKs on the hand.

FIG. 8-4. Cutaneous horn on the shoulder.

FIG. 8-5. Actinic cheilitis on the lower lip.

Cryotherapy is the most widely used modality to treat AKs. It is a quick, effective, and generally well-tolerated in-office procedure. The lesions are destroyed by freezing with liquid nitrogen (−196.5°C), which crystallizes the tumor cells, producing necrosis and tissue destruction. Blisters often form and dry into crusts, usually healing within 1 to 2 weeks. Potential adverse effects include pain, hypopigmentation, or scarring, which may be of concern in cosmetically sensitive areas. The advantage is that it requires one visit for treatment, and has been traditionally covered by insurers compared to prescription immunotherapies which can be more costly.

Treatment Modalities for Actinic Keratoses |

TREATMENT MODALITY (BRAND NAME) | REDUCTION OF LESIONS |

Cryotherapy | 88% |

Imiquimod (Aldara, Zyclara) | 87% |

5-fluorouracil (Efudex, Carac, Fluoroplex) | 86% |

Ingenol mebutate (Picato) | 85% |

Diclofenac (Solaraze) | 64% |

Photodynamic therapy | 78% |

Chemical peels: glycolic acid, salicylic acid, trichloroacetic acid | High |

Dermabrasion, laser resurfacing | High |

Curettage can be used to debulk hypertrophic AKs immediately following a shave biopsy, which is sent for histology to exclude invasive SCC. The provider uses a curette to scrape off the friable, damaged keratinocytes until normal, firm dermal tissue is reached. Electrocautery is used to control any bleeding. The procedure should only be performed by clinicians trained and experienced with this technique. Disadvantages of curettage include risk of hypopigmented, atrophic and/or hypertrophic scarring.

Field therapy

Patients can present with clinically well-defined AKs, as well as subclinical lesions in moderately and severely photodamaged skin. There are medical and procedural options that can provide field treatment to larger areas, treating both types of lesions.

Immunotherapy may be considered for both local and field therapy. There are several FDA-approved topical agents outlined in Table 8-2 with varied mechanism of action, dosages, contraindications, side effects, and duration of therapy. In general, patients receiving topical therapy are advised to avoid application to the mucous membranes and UVR exposure during and immediately after therapy. Use of shade, full-brimmed hat, and sun screen are suggested if patients will be outdoors. Common side effects for almost all topical therapies include allergic contact dermatitis, burning, crusting, dryness, edema, erosion, erythema, hyperpigmentation, irritation, pain, soreness, and ulceration (Figure 8-6A). Patients may struggle with the red, crusted appearance during treatment, but are usually pleased with the final cosmetic results. On the other hand, the advantages of topical immunotherapy are treatment of subclinical lesions and cosmetic outcomes (Figure 8-6B).

Topical Actinic Keratoses Immunotherapy |

FIG. 8-6. A: AKs treated with topical 5-fluorouracil. B: One month after completed treatment.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a form of phototherapy which utilizes a photosensitizing agent which is activated by a timed exposure to a light source. This process selectively causes destruction of the damaged cells. Many patients compare the experience to that of a severe sunburn. PDT has a better cosmetic result than cryotherapy and 5-FU; however, the treatment causes significant discomfort and burning. Patients must avoid all sun exposure for at least 3 days posttreatment. PDT is performed in dermatology offices.

Dermabrasion is an in-office procedure used occasionally for treatment of AKs. It physically removes the surface of the epidermis using a surgical sanding tool or laser therapy. The skin is red and abraded initially, but then heals with healthy keratinocytes.

Chemical peels (medium depth), using trichloroacetic acid or glycolic acid, exfoliate the stratum corneum and can be effective. The skin can become very red and irritated initially, but then skin heals with a soft, smooth texture. Deep chemical peels are rarely used due to risk of systemic and cutaneous complications.

Laser resurfacing with carbon dioxide or erbium: YAG lasers are used for the treatment of extensive actinic damage and epithelial dysplasia implicated in the development of aggressive skin cancer. Sustained efficacy with laser resurfacing has not been established.

Special Consideration

Regular preventive strategies and early treatment of precancerous AKs and SCCIS are very important in the immunosuppressed patient. These lesions can rapidly develop into aggressive, invasive skin cancers.

Prognosis and Complications

There are few, if any, complications associated with treatment of AKs by experienced providers. Complications like scarring and systemic side effects vary with each modality. Patients may report resolution after treatment only to experience recurrence after new sun exposure. Up to 20% of AKs may progress to invasive SCC.

Referral and Consultation

Patients with an extensive number of AKs, poorly defined lesions, and those resistant to treatment should be referred to dermatology. Primary care APC’s would be prudent to maintain a low threshold for referral to dermatology or plastic surgery.

Patient Education and Follow-up

AKs are preventable with consistent, careful sun-protective and sun-safety measures. Regular application of sunscreen has been shown to actually decrease the number of AKs and thereby significantly decrease SCC development by almost 40%. Patients treated for AKs must be counseled about the effectiveness, risk for recurrence, and progression. Recommended follow-up after completed treatment is 6 to 12 months.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

While the incidence of many cancers has been on the decline, SCC has doubled over the past 40 years. This development is likely due, at least in part, to an increasing exposure of the population to UVR—especially UVB radiation. Patients who develop SCCs tend to be fair with a history of chronic or intense, intermittent sun exposure and have clinical signs of solar elastosis, including freckles, lentigines, and pigmentary dyschromia.

SCC occurs more often in men and in older patients. While basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in patients of Caucasian, Hispanic, Chinese, and Japanese descent, SCC is the most common type of skin cancer that occurs in African Americans and Asian Indians. Melanin provides a sun-protection factor (SPF) of approximately 13.4 in African American skin, compared to 3.4 in Caucasian skin, which unfortunately creates the misconception that dark skin is not vulnerable to skin cancer. SCC lesions in people with dark skin tones are often diagnosed at later stages and may be more advanced and potentially fatal. SCCs occurring in these patients are often secondary to scarring or chronic inflammation. The metastatic rate of SCC caused by chronic UVR in Caucasians is <10%, whereas SCC caused by chronic scarring in blacks is nearly 30%.

Other subsets of patients are also at increased risk for developing SCC. A history of lymphoproliferative disease is an independent risk factor for SCC, which does not revert back to normal with control of the disease. HIV patients are more susceptible to human papilloma virus (HPV) infections and therefore three times more likely to develop SCC than the general population. The health of 30,000 Americans who are organ transplant recipients (OTRs) rely on immunosuppression to prevent rejection of the new organ. Unfortunately, this increases their risk of skin infections and skin cancers. By 20 years post transplantation, 40% of OTRs in the United States will eventually develop skin cancers, especially SCCs which behave far more aggressively than those in the immunocompetent patient.

Pathophysiology

SCC is a malignant epithelial tumor arising from a proliferation of keratinocytes (squamous cells) from the epidermis. Damage to the keratinocytes results in a mutation of cellular DNA. Irregular nests of the damaged cells form a tumor which invades into the dermis.

Clinical Presentation

Invasive SCC presents as papules, plaques, or nodules which develop in sun-exposed areas, including areas of thinning hair at the scalp and at the anterior lower extremities (Figure 8-7). Tumors may have a smooth or hyperkeratotic surface or they may develop a cutaneous horn. The SCC grows slowly, becoming increasingly indurated over time, and may eventually ulcerate. Invasive SCC may bleed, become tender or painful.

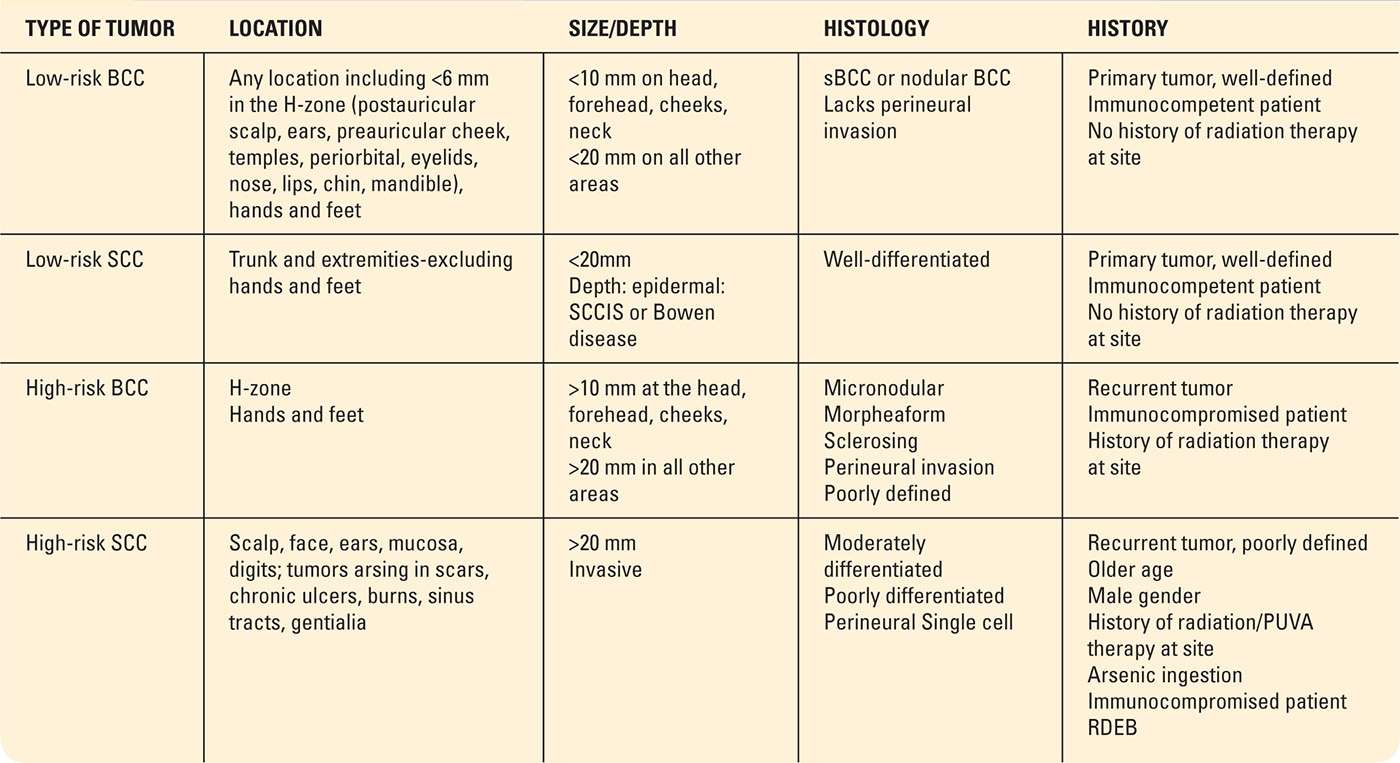

“High-risk” SCCs are tumors which present a high risk for recurrence or metastasis. Lesion characteristics and patient history are vital for an accurate assessment of risk in SCC (Table 8-3).

Location. Seventy percent of SCCs develop at the head and neck and 15% at the upper extremities (Figure 8-8A). SCCs which develop at the ears, lips, tongue, genitalia, and distal extremities have a much higher rate of recurrence than those that develop at other locations. Additionally, the scalp is increasingly being considered a high-risk location as SCC can penetrate the bony outer table of the skull (Figure 8-8B).

Size. SCCs which are greater than 2 cm have up to three times the metastatic rate of smaller tumors.

Etiology. SCCs which develop in scars, sinus tracts, chronic ulcers, and areas of previous radiation also present higher rates of recurrence (Figure 8-9).

FIG. 8-7. Invasive SCC of the left shin.

Cellular Behavior. Certain SCC cellular subtypes may also present aggressive behavior. Those which are poorly differentiated invade nerves or blood vessels, or those which develop in isolation as single cells present a particularly high risk for recurrence.

Subtypes of SCC

SCCIS is an AK which has progressed through the full thickness of the epidermis and extended into the hair follicles (follicular or adnexal extension). Clinically, SCCIS is thicker than an AK and has an erythematous base (Figure 8-10). They enlarge and become increasingly tender, bleed easily, or ulcerate.

Bowen disease is an SCCIS which develops in hair-bearing epithelium, often in areas with limited sun exposure such as the trunk or extremities (Figure 8-11).

Bowenoid papulomatosis (BP) is Bowen disease thought to be induced by HPV. Lesions are solitary, sharply defined, red papules or plaques which ooze or crust. BP is usually located on the genitals, and can affect both males and females. Up to 5% of BP may become invasive carcinoma.

Erythroplasia of Queyrat is an SCCIS that develops in the mucosal epithelium (glans and prepuce of the penis) often in older, uncircumcised males. It presents as a solitary, sharply defined, shiny, red plaque which may ulcerate but is generally nontender. Up to 30% of cases may become invasive carcinoma.

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a low-grade SCC variant which develops in sun-exposed areas (Figure 8-12). Clinically, it presents as a 1- to 2.5-cm dome-shaped, skin color to red, firm nodule which can be tender. KAs have central, hyperkeratotic crusting or horn, often described as a volcano. Tumors grow very quickly and may involute within 6 months.

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is also a low-grade SCC variant developing in the genital or oral regions, but can be found on the sole of the foot and other sites of chronic irritation and inflammation (Figure 8-13). VC is an exophytic, verrucal, or fungating tumor associated with the HPV. It is not an aggressive tumor; however, the location of the lesions can create high morbidity for the patient.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Squamous cell carcinoma |

• Actinic keratoses

• Basal cell carcinoma

• Seborrheic keratosis

• Psoriasis

• Eczema

• Verruca vulgaris

• Melanoma

• Extramammary Paget disease

It is worthwhile to note an important differential diagnosis, extramammary Paget disease (EMPD). It is a rare, slow-growing intraepithelial adenocarcinoma derived from keratinocytes in the epidermis which can affect anogenital skin (outside of the mammary gland). It occurs more often in older women. Lesions are large, eczematous, and erythematous plaques which may be asymptomatic or painful. EMPD is characteristically very pruritic (Figure 8-14). The differential for EMPD includes eczematous dermatitis, psoriasis, tinea, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen sclerosis, and lichen planus. Suspicious lesions should be biopsied if they do not resolve after 6 weeks of treatment. There is a 12% rate of recurrence after Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), and 25% of patients have a nonassociated genitourinary, rectal, or breast carcinoma.

Characteristics of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. |

H-Zone, high risk zone (Figure 8-27); BCC, basal cell carcinoma; sBCC, superficial BCC; PUVA, psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation; RDEB, recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SCCIS, squamous cell carcinoma in situ. From Lazareth, V. (2013). Management of non-melanoma skin cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 29(3), 182–194.

Diagnosis

FIG. 8-8. A: SCC on the left preauricular cheek. B: Large SCC on the left parietal scalp.

FIG. 8-9. SCC in traumatic scars.

FIG. 8-10. SCC in situ on the hand.

FIG. 8-11. Bowen disease on the finger.

FIG. 8-12. Keratoacanthoma on the upper arm.

FIG. 8-13. Verrucous carcinoma on the palm.

FIG. 8-14. Extramammary Paget disease on the left perineum.

Diagnosis

A shave biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of SCC. If the sample obtained is too shallow and does not include a portion of the dermal–epidermal junction, an invasive SCC could be misdiagnosed as in situ lesion, risking incomplete treatment with potential for an aggressive recurrence. A repeat biopsy should be performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree