Chapter 7 Pre-hospital management, transportation and emergency care

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

For burn victims, there are usually two phases of transport. The first is the entry of the burn patient into the emergency medical system with treatment at the scene and transport to the initial care facility. The second phase is the assessment and stabilization of the patient at the initial care facility and transportation to the burn intensive care unit.1 With this perspective in mind, this chapter reviews current principles of optimal pre-hospital management, transportation, and emergency care.

Pre-hospital care

Prior to any specific treatment, a patient must be removed from the source of injury and the burning process stopped. As the patient is removed from the injuring source, care must be taken so that a rescuer does not become another victim.2 All caregivers should be aware of the possibility that they may be injured by contact with the patient or the patient’s clothing. Universal precautions, including wearing gloves, gowns, masks, and protective eye wear, should be used whenever there is likely contact with blood or body fluids. Burning clothing should be removed as soon as possible to prevent further injury.3 All rings, watches, jewelry, and belts should be removed as they can retain heat and produce a tourniquet-like effect with digital vascular ischemia.4 If water is readily available, it should be poured directly on the burned area. Early cooling can reduce the depth of the burn and reduce pain, but cooling measures must be used with caution, since a significant drop in body temperature may result in hypothermia with ventricular fibrillation or asystole. Ice or ice packs should never be used, since they may cause further injury to the skin or produce hypothermia.

Removal of a victim from an electrical current is best accomplished by turning off the current and by using a non-conductor to separate the victim from the source.5

On-site assessment of a burned patient

Primary assessment

Exposure to heated gases and smoke from the combustion of a variety of materials results in damage to the respiratory tract. Direct heat to the upper airways results in edema formation, which may obstruct the airway. Initially, 100%-humidified oxygen should be given to all patients when no obvious signs of respiratory distress are present. Upper airway obstruction may develop rapidly following injury, and the respiratory status must be continually monitored in order to assess the need for airway control and ventilator support. Progressive hoarseness is a sign of impending airway obstruction. Endotracheal intubation should be done early before edema obliterates the anatomy of the area.3

The patient’s chest should be exposed in order to adequately assess ventilatory exchange. Circumferential burns may restrict breathing and chest movement. Airway patency alone does not assure adequate ventilation. After an airway is established, breathing must be assessed in order to insure adequate chest expansion. Impaired ventilation and poor oxygenation may be due to smoke inhalation or carbon monoxide intoxication. Endotracheal intubation is necessary for unconscious patients, for those in acute respiratory distress, or for patients with burns of the face or neck which may result in edema which causes obstruction of the airway.3 The nasal route is the recommended site of intubation. Assisted ventilation with 100%-humidified oxygen is required for all intubated patients.

Blood pressure is not the most accurate method of monitoring a patient with a large burn because of the pathophysiologic changes which accompany such an injury. Blood pressure may be difficult to ascertain because of edema in the extremities. A pulse rate may be somewhat more helpful in monitoring the appropriateness of fluid resuscitation.6

Secondary assessment

After completing a primary assessment, a thorough head-to-toe evaluation of a patient is imperative.7 A careful determination of trauma other than obvious burn wounds should be made. As long as no immediate life-threatening injury or hazard is present, a secondary examination can be performed before moving a patient; precautions such as cervical collars, backboards, and splints should be used.8 Secondary assessment should examine a patient’s past medical history, medications, allergies, and the mechanisms of injury.

Pre-hospital care of wounds is basic and simple, because it requires only protection from the environment with an application of a clean dressing or sheet to cover the involved part. Covering wounds is the first step in diminishing pain. If it is approved for use by local/regional EMS, narcotics may be given for pain, but only intravenously in small doses and only enough to control pain. Intramuscular (IM) or subcutaneous routes should never be used, since fluid resuscitation could result in unpredictable patterns of uptake.4 No topical antimicrobial agents should be applied in the field.4,9 The patient should then be wrapped in a clean sheet and blanket to minimize heat loss and to control temperature during transport.

Transport to hospital emergency department

Rapid, uncontrolled transport of a burn victim is not the highest priority, except in cases where other life-threatening conditions coexist. In the majority of accidents involving major burns, ground transportation of victims to a hospital is available and appropriate. Helicopter transport is of greatest use when the distance between an accident and a hospital is 30–150 miles or when a patient’s condition warrants.10 Whatever the mode of transport, it should be of appropriate size, and have emergency equipment available as well as trained personnel, such as a nurse, physician, paramedic, or respiratory therapist.

Assessment at the initial care facility

The assessment of a patient with burn injuries in a hospital emergency department is essentially the same as outlined for a pre-hospital phase of care. The only real difference is the availability of more resources for diagnosis and treatment in an emergency department. As with other forms of trauma, the primary survey begins with the ABCs, and the establishment of an adequate airway is vital. Endotracheal intubation should be accomplished early if impending respiratory obstruction or ventilatory failure is anticipated, because it may be impossible after the onset of edema following the initiation of fluid therapy. Securing an endotracheal tube may be difficult because traditional methods often do not adhere to burned skin, and tubes are easily dislodged. One method of choice includes securing an endotracheal tube with woven tape, umbilical cord, under the ears as well as over the ears.11 While doing assessments and making interventions for life-threatening problems in the primary survey, precautions should be taken to maintain cervical spine immobilization until injuries to the spine can be ruled out.

Following a primary survey, a thorough head-to-toe evaluation of a patient should be done. This includes obtaining a history as thorough as circumstances permit. The history should include the mechanism and time of the injury and a description of the surrounding environment, such as whether injuries were incurred in an enclosed space, the presence of noxious chemicals, the possibility of smoke inhalation, and any related trauma. A complete physical examination should include a careful neurological examination, as evidence of cerebral anoxic injury can be subtle. Patients with facial burns should have their corneas examined with fluorescent staining. Routine admission laboratories should include a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatine. Pulmonary assessment should include arterial blood gases, chest X-rays, and carboxyhemoglobin.12

Emergency treatment at the initial care facility

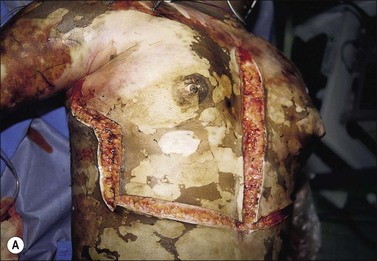

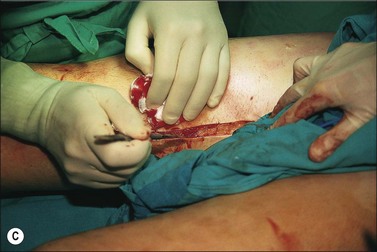

All extremities should be examined for pulses, especially with circumferential burns. Evaluation of pulses can be assisted by use of a Doppler ultrasound flowmeter. If pulses are absent, the involved limb may need urgent escharotomy for release of the constrictive, unyielding eschar (Fig. 7.1). In circumferential chest burns, escharotomy may also be necessary to relieve chest wall restriction and improve ventilation. Escharotomies may be performed at the bedside under IV sedation using electrocautery. Midaxial incisions are made through the eschar but not into subcutaneous tissue of the eschar in order to assure adequate release. Limbs should be elevated above the heart level. Pulses should be monitored for 48 h.12

(Fig. 7.1a Reproduced from Herndon DN, Desai MH, Abston S, et al. Residents Manual. Galveston: Shriner’s Burns Hospital, and the University of Texas Medical Branch 1992:1-17.)

Evaluation of wounds

After the primary and secondary surveys are completed and resuscitation is underway, a more careful evaluation of burn wounds is performed. The wounds are gently cleaned, and loose skin and in large wounds blisters greater than 2 cm are debrided (see Ch. 6). Blister fluid contains high levels of inflammatory mediators, which increase burn wound ischemia. The blister fluid is also a rich media for subsequent bacterial growth. Deep blisters on the palms and soles may be aspirated instead of debrided in order to improve patient comfort. After burn wound assessment is complete, the wounds are covered with a topical antimicrobial agent and appropriate burn dressings or a biological dressing is applied.

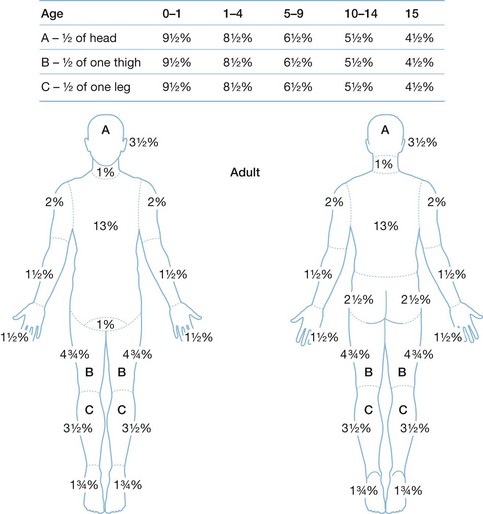

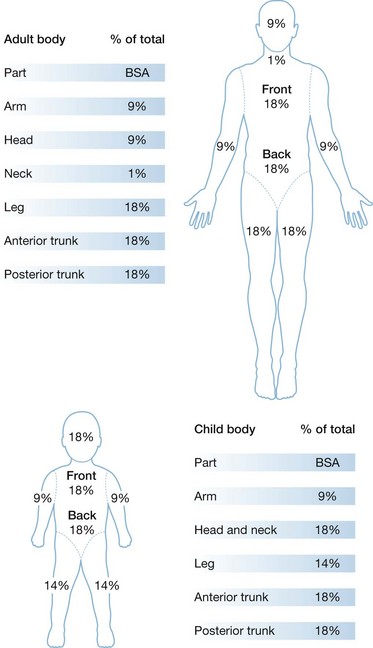

An estimate of burn size and depth assists in making a determination of severity, prognosis, and disposition of a patient. Burn size directly affects fluid resuscitation, nutritional support, and surgical interventions. The size of a burn wound is most frequently estimated by using the Rule-of-Nines method (Fig. 7.2). A more accurate assessment can be made of a burn injury, especially in children, by using the Lund and Browder chart, which takes into account changes brought about by growth (Fig. 7.3).4,9 The American Burn Association identifies certain injuries as usually requiring a referral to a burn center. Patients with these burns should be treated in a specialized burn facility after initial assessment and treatment at an emergency department. Questions about specific patients should be resolved by consultation with a burn center physician (Box 7.1).4,13

Figure 7.2 Estimation of burn size using the Rule-of-Nines.

(From: Advanced Burn Life Support Providers Manual. Chicago, IL: American Burn Association; 2010.)

Box 7.1

Criteria for transfer of a burn patient to a burn center

• Second-degree burns greater than 10% total body surface area (TBSA)

• Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, and major joints

• Electrical burns including lightning injuries

• Any burn with concomitant trauma in which the burn injuries pose the greatest risk to the patient

• Patients with pre-existing medical disorders that could complicate management, prolong recovery, or affect mortality

• Hospitals without qualified personnel or equipment for the care of critically burned children.

Reproduced from the Advanced Burn Life Supporters Manual. Chicago, IL: American Burn Association; 2005.

Fluid resuscitation

Establishment of IV lines for fluid resuscitation are necessary for all patients with major burns including those with inhalation injury or other associated injuries. These lines are best started in the upper extremity peripherally. A minimum of two large-caliber IV catheters should be established through non-burned tissue if possible, or through burns if no unburned areas are available. The ABLS 2010 Fluid Resuscitation Formula of Ringer’s lactate solution should be infused at 2 mL/kg/% total body surface area (TBSA) which is burned.1,4,9 Children must have additional fluid for maintenance.14

Taking into account the increased evaporative water loss in the formula for fluid resuscitation for pediatric patients, the initial resuscitation should begin with 5000 mL/m2/% TBSA burned/day + 2000 mL/m2/BSA total/day 5% dextrose in Ringer’s lactate. This formula calls for one-half of the total amount to be given in the first 8 h post-injury with the remainder given over the following 16 h (Box 7.2).14

Box 7.2

Burn fluid resuscitation formula

Fluid administration – Ringer’s lactate:

Reproduced with permission from: Herndon DN, Rutan RL, Rutan TC. Management of the pediatric patient with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993; 14(1):3-8.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree