Pityriasis Rosea: Introduction

|

The term pityriasis rosea (PR) was first used by Gibert in 1860 and means pink (rosea) scales (pityriasis).1 PR is a common acute, self-limited skin eruption that typically begins as a single thin oval scaly plaque on the trunk (“herald patch”) and is typically asymptomatic. The initial lesion is followed several days to weeks later by the appearance of numerous similar-appearing smaller lesions located along the lines of cleavage of the trunk (a so-called Christmas tree pattern). PR most commonly occurs in teenagers and young adults, and is most likely a viral exanthem associated with reactivation of human herpes virus 7 (HHV-7) and sometimes HHV-6,2–5 the viruses responsible for rubeola (see Chapter 192). Possible treatment may focus on associated pruritus. One study suggests that administration of high-dose acyclovir for 1 week, if initiated early in the disease course, hastens recovery from PR.6

Epidemiology

PR is reported in all races throughout the world, irrespective of climate.7–9 The average annual incidence at one center was reported to be 0.16% (158.9 cases per 100,000 person-years).9 Although PR is usually considered to be more common in the spring and fall months in temperate zones, seasonal variation has not been borne out in studies performed in other parts of the world. Clustering of cases can occur and has been used to support an infectious etiology for PR, although this is not a consistent feature observed in all communities.8 Most studies have shown a slight female preponderance of approximately 1.5:1.7,9 PR most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 35 years.9 It is rare before age 2 years and after age 65 years. Recurrences of PR are rare, which suggests lasting immunity after an initial episode of PR.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Historically, PR has been considered to be caused by an infectious agent, given (1) the resemblance of the rash to known viral exanthems; (2) rare recurrences of PR that suggest lifelong immunity after one episode; (3) occurrence of seasonal variation in some studies; (4) clustering in some communities; and (5) the appearance of flu-like symptoms in a subset of patients. Numerous studies over the past 50 years have explored various pathogens as possible causes of PR. These pathogens have included bacteria, fungi, and, most notably, viruses. Beginning with a study by Drago and colleagues in 1997,2 most recent PR etiologic and pathogenic studies have been focused on two ubiquitous viruses: (1) HHV-7 and (2) HHV-6. Critical evaluation of the medical and scientific literature on PR reveals neither credible nor reproducible evidence that PR is associated with any pathogen other than HHV-7 and HHV-6.10

Indeed, the best scientific evidence suggesting that PR is a viral exanthem associated with reactivation of either HHV-7 or HHV-6 (and sometimes with both viruses) is strong.2–5,11–13 The most definitive and compelling study on HHVs and PR was by Broccolo and colleagues in 2005.4 Using sensitive and quantitative techniques, investigators have collectively shown that (1) HHV-7 DNA, and less commonly HHV-6 DNA, can be readily detected in cell-free plasma or serum samples from many patients with PR, but not in serum or plasma from healthy individuals or patients with other inflammatory skin diseases; (2) HHV-7 messenger RNA and protein, and less commonly HHV-6 messenger RNA and protein, can be detected in scattered leukocytes found in perivascular and perifollicular regions within PR lesions, but not in normal skin or skin from patients with other inflammatory skin diseases; (3) HHV-7- and HHV-6-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibody elevations in the absence of virus-specific IgG antibodies do not occur in PR patients, whereas in primary viral infections elevation of IgM antibodies alone is typical; and (4) HHV-7 and HHV-6 DNA are present in saliva of individuals with PR, which is not observed in those with a primary infection with these viruses. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that PR is a viral exanthem associated with systemic reactivation of HHV-7 and, to a lesser extent, HHV-6. Patients are viremic, which may explain associated flu-like symptoms in some patients, and they generally do not have infected epithelial cells or large viral loads within skin lesions, which explains the difficulty in detecting these viruses by electron microscopy and by nonnested polymerase chain reaction testing.

Despite these findings, there is still controversy over the role of HHV-7 and HHV-6 in the etiology of PR, because a number of studies with “negative” results have failed to support a causative role for HHV-7 and HHV-6 in this disease.14–16 Whereas the studies with positive results have used the most sensitive, specific, and calibrated techniques for virologic studies and reports have been published in high-quality journals, the studies with negative results either used laboratory methods that were not particularly sensitive, calibrated, or quantifiable, or focused on peripheral blood mononuclear cells rather than cell-free plasma or serum.

Correct interpretation of the recent viral literature on PR also requires proper understanding of the biology of HHV-7 and HHV-6. HHV-7 and HHV-6 are closely related β-herpes viruses, and the clinical diseases and biology associated with this group of HHVs are not as well studied as those of the α-herpes viruses (herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus) and the γ-herpes viruses (Epstein–Barr virus and Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus). HHV-6 and HHV-7 are ubiquitous, with 90% of the US population infected with HHV-6 by the age of 3 years17 and 90% of the US population infected with HHV-7 by the age of 5 years.18 Unlike the α-herpes viruses, HHV-7 and HHV-6 do not infect keratinocytes, but instead infect CD4+ T cells within blood and are retained within these cells in a latent form in most individuals.10,17–19 These cells are the likely source of cell-free viral DNA found in plasma or serum samples of patients with PR. They are also the likely source of the scattered perivascular and perifollicular virus-positive cells observed within some lesions of PR.3,4

It is important to note that the concept that PR represents a reactive viral exanthem containing few infected cells within skin lesions and viral reactivation within circulating blood CD4+ T cells is perfectly analogous to that of the disease roseola, which is well accepted to be caused by primary infection with either HHV-6 or HHV-720,21 (see Chapter 192). Children with roseola are viremic and skin lesions generally do not contain infected cells.22 Complete understanding of the role of HHV-7 and HHV-6 in the pathogenesis of PR is lacking at this time. For example, the mechanisms by which HHV-7 and HHV-6 are reactivated are unknown. As well, the characteristic distribution of lesions and differences in lesional and nonlesional skin are unexplained.

Clinical Findings

In classic PR, patients usually describe the onset of a single truncal skin lesion followed several days to weeks later by the onset of numerous smaller lesions on the trunk. Pruritus is severe in 25% of patients with uncomplicated PR, slight to moderate in 50%, and absent in 25%. In a minority of patients, flu-like symptoms have been reported, including general malaise, headache, nausea, loss of appetite, fever, and arthralgias.

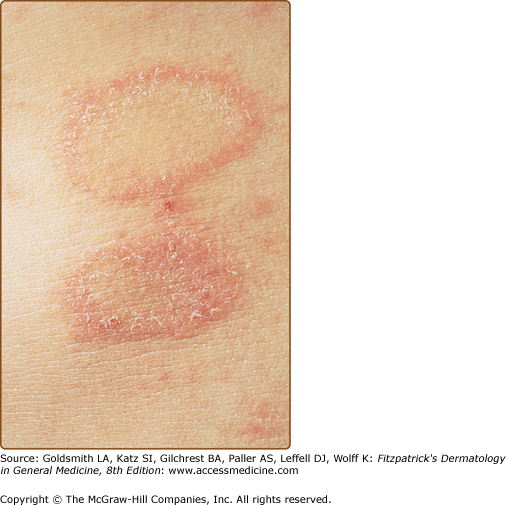

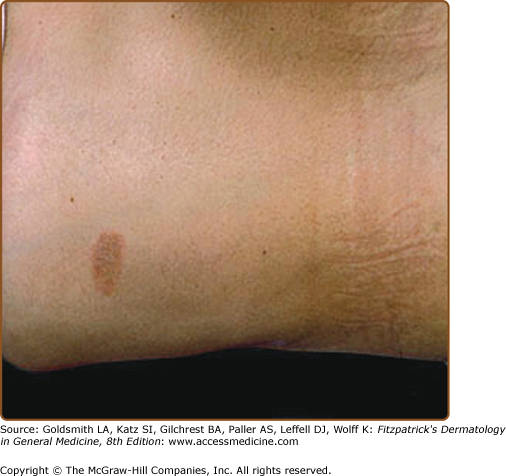

The primary plaque of PR, or herald patch (Figs. 42-1, 42-2, and 42-3 and see eFigs. 42-3.1 and 42-3.2), is seen in 50%–90% of cases. It is normally well demarcated; 2–4 cm in diameter; oval or round; salmon colored, erythematous, or hyperpigmented (especially in individuals with darker skin); and demonstrates a fine collarette of scale just inside the periphery of the plaque. When the plaque is irritated, it may have an eczematous papulovesicular appearance (eFig. 42-3.3). The primary plaque is usually located on the trunk in areas covered by clothes, but sometimes it is on the neck or proximal extremities. Localization on the face or penis is rare. The site of the primary lesion does not differ between males and females.

The interval between the appearance of the primary plaque and the secondary eruption can range from 2 days to 2 months, but the secondary eruption typically occurs within 2 weeks of the appearance of the primary plaque. At times, the primary and secondary lesions may appear at the same time. The secondary eruption occurs in crops at intervals of a few days and reaches its maximum in approximately 10 days. Occasionally, new lesions continue to develop for several weeks. The symmetric eruption is localized mainly to the trunk and adjacent regions of the neck and proximal extremities (Fig. 42-4). The most pronounced lesions extend over the abdomen and anterior surface of the chest as well as over the back (Figs. 42-5, 42-6, and 42-7 and eFigs. 42-7.1 and 42-7.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree