The presence of pigmentation in skin is largely determined by genetic makeup. Skin type is related to the amount of melanin that is produced by an individual. A general understanding of the process of melanin synthesis is essential to understanding the conditions of dyspigmentation. Disturbances in the process of pigment production can yield significant alterations in one’s appearance. Cosmetic and physiologic changes may occur as a result of genetic, environmental, and even pharmacologic influences. The sun alone can play a major role, not only in the overproduction of pigmentation which is seen in normal tanning but as a predisposing factor in the development of skin cancer. In this chapter, we review the biology and function of melanocytes, the role of melanosomes in the production of melanin, and the common types of dyspigmentation which can result when this normal process is interrupted.

BIOLOGY OF PIGMENTATION

Melanocytes are derived from the neural crest and migrate to the epidermis, hair follicles, uveal tract of the eye (choroid, ciliary body, and iris), the leptomeninges, and the inner ear (cochlea). They contain the melanin-producing cells called melanosomes, where, under genetic influence, and with the aid of the enzyme tyrosinase, melanin is synthesized. There are two types of melanin: eumelanin (brown/black) and pheomelanin (yellow-red). The melanocyte resides in the basal layer of the epidermis and via its dendritic processes attaches to the keratinocytes and deposits the melanin-containing melanosome. A person’s skin color is determined by the size and number of these melanosomes, the amount of melanin they produce, and their distribution within the epidermis.

DISORDERS OF PIGMENT LOSS

Hypopigmentation and depigmentation can occur if there is a loss of melanocytes, an inability of melanocytes to produce melanin, or an inability to transport melanin correctly. The term hypopigmentation refers to a partial loss of melanocytes, while depigmentation refers to a total loss of melanocytes. Patients with large body surface areas (BSAs) of pigment abnormality may be challenging for the clinician to identify a patient’s normal skin color.

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is an unpredictable disease of depigmentation. The exact cause of melanocyte destruction is unknown. It affects males and females equally, and is present in all ethnicities. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated to be 1% of the world’s population, with 50% of all cases occurring before the age of 20 years. Thirty percent of patients with vitiligo have other family members who also have the disease. Some people attribute the initial onset to emotional stress, illness, or skin trauma such as sunburn.

Risk factors for developing vitiligo include heredity, autoimmune disease, especially Hashimoto thyroiditis, and a variety of systemic diseases such as diabetes, pernicious anemia, Addison disease, and hypoparathyroidism. Interestingly, patients who have received bone marrow transplants, or lymphocyte infusions from a donor with vitiligo, have developed vitiligo themselves.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of depigmentation in vitiligo is not well understood. It is thought that there is an absence of functional melanocytes caused by both genetic and nongenetic factors. In addition to the belief that vitiligo is hereditary, it is theorized that specific autoantibodies are directed against tyrosinase, the enzyme that converts tyrosine into melanin, resulting in pigment loss. Others suggest that vitiligo is caused by an intrinsic defect in the structure and function of melanocytes or that there is a defective free-radical defense, which results in the destruction of melanocytes, leading to depigmentation.

Clinical presentation

A patient with vitiligo typically presents with well-demarcated, depigmented white macules or patches surrounded by normal skin. The onset of the lesions is insidious with expanding, irregularly shaped patches that rarely have inflamed borders. Hair follicles present in the depigmented patch are usually white. When the scalp area is involved, it usually presents as a solitary patch called poliosis or white forelock (Figure 18-1). The eyebrows and eyelashes may also be affected. There may also be focal blue-gray hyperpigmented macules on the skin representing melanin incontinence.

FIG. 18-1. Poliosis or white forelock is the localized loss of pigment in the hair and skin on the scalp and can occur in the eyebrow and eyelashes.

There are six different types of vitiligo: localized, segmental, generalized, universal, acrofacial, and mucosal.

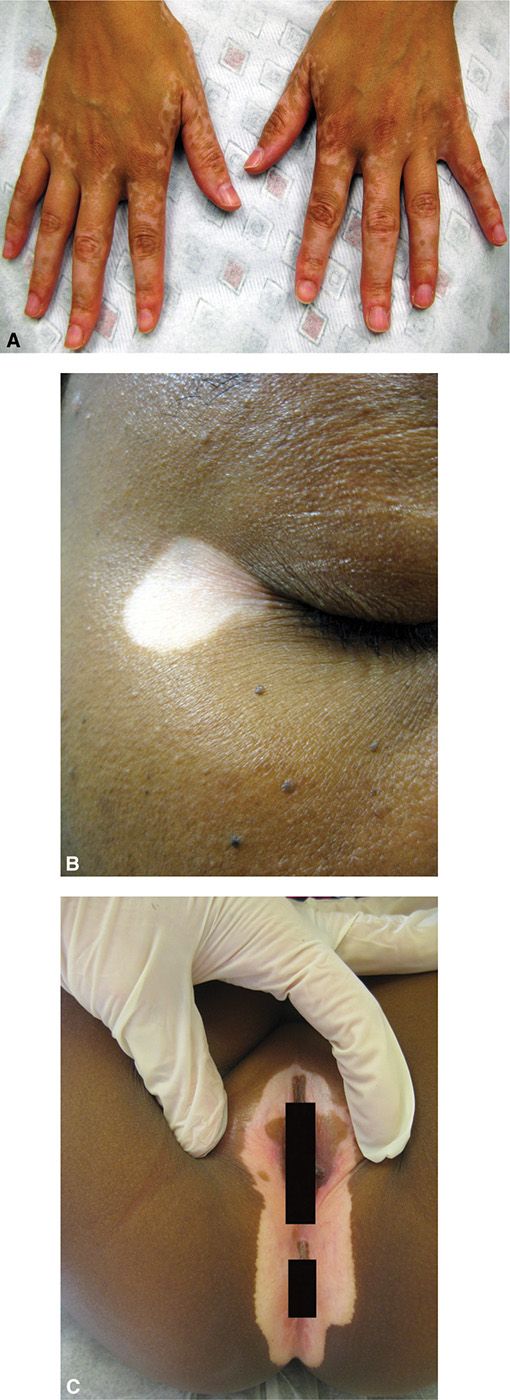

Generalized vitiligo is the most common type, accounting for 90% of all cases. It is usually symmetrically distributed on the face, upper chest, dorsal hands, axillae, and groin (Figure 18-2A). It has a predilection for orifices, including the eyes (Figure 18-2B), nostrils, mouth, nipples, umbilicus, and anogenital areas. Sites of trauma are commonly affected.

Localized vitiligo may affect one nondermatomal site, or asymmetrically affect one region (e.g., an extremity).

Segmental vitiligo has a distribution similar to localized vitiligo, but is often dermatomally distributed. It is more often seen in younger patients, and is less likely to be related to autoimmune disease.

Acrofacial vitiligo affects facial orifices and/or distal fingers and toes (think “lips and tips”).

Mucosal vitiligo, as its name clearly states, affects the mucous membranes alone, and is commonly seen on the lips and genital and perianal areas (Figure 18-2C).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Vitiligo

• Chemical leukoderma

• Leukoderma associated with melanoma

• Postinflammatory depigmentation

• Tinea versicolor

• Morphea

• Lichen sclerosis

• Pityriasis alba

Diagnostics

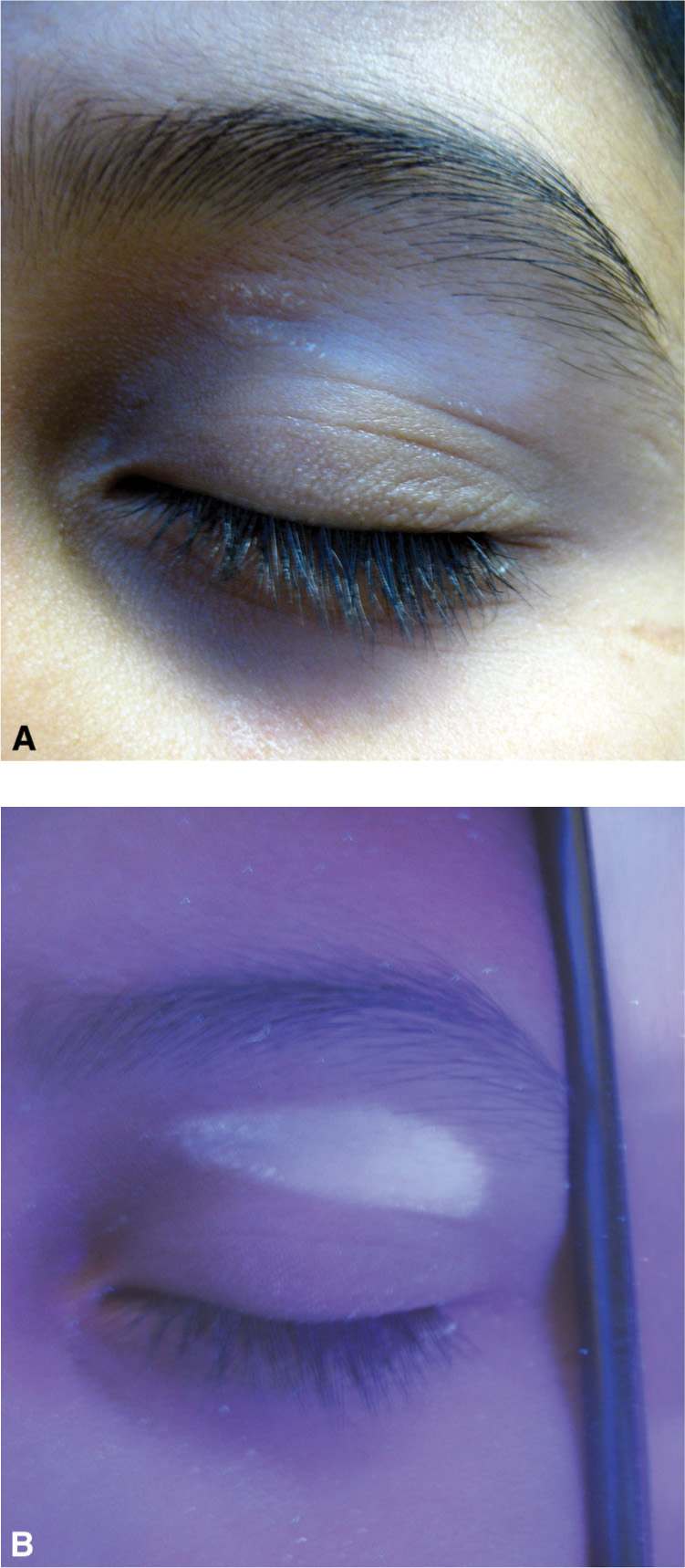

The diagnosis of vitiligo is usually made based on clinical findings. A skin biopsy will show an absence of melanocytes and sometimes inflammation. Vitiligo macules/patches may not be obvious upon a general examination, especially around the eyes, nose, axilla, hands/fingers, and groin. Wood’s lamp examination is a low-cost and convenient diagnostic tool that can help differentiate depigmented lesions from hypopigmented lesions. Lesions become markedly enhanced on wood’s lamp examination and help to define specific areas of depigmentation (Figure 18-3A, B).

Because vitiligo is often associated with systemic disease, it is important to screen for underlying thyroid disease, pernicious anemia, and diabetes. If indicated, laboratory studies should include CBC, TSH, T3, T4, glycosylated hemoglobin, thyroid antibodies (antithyroglobulin and antithyroid peroxidase antibodies), and antinuclear antibody (ANA) screening.

Management

In patients with fair skin, nontreatment may be an option as the disfigurement from vitiligo may not be severe. However, these patients must adhere to strict sun-protective practices. Camouflage makeup can be used as well. Some brand-name products available for patients with dyspigmentation are Dermablend, Dermacolor, Keromask, Veil Cover, Perfect Cover, and Covermark. Aestheticians can be helpful in assisting patients with application and matching their skin tone.

Topical corticosteroids (TCS). TCS are the treatment of choice for vitiligo when small areas of skin are involved (<20% BSA) and for children. High-potency TCS should be initiated with these patients and continued for 2 months. If there is no response, then the treatment should be discontinued. If the lesions are repigmenting, a slow taper to lower-potency TCS should be continued for 4 to 6 months. An exception to this general approach is lesions located around the eyes due to concern for increased intraocular pressure. Clinicians should regularly monitor patients for side effects and response to treatment.

FIG. 18-2. A: Vitiligo on the dorsal hands. B: Vitiligo on the lateral eye. C: Vitiligo at the anogenital area.

FIG. 18-3. A: Vitiligo can have a subtle presentation that is difficult to discern, especially in patients with fair skin. B: Wood’s light examination can be used to accentuate areas of pigment loss and help to diagnose vitiligo.

It is important to educate the patient on the risks of using TCS, especially on the face, including, but not limited to acne, atrophy, and telangiectasias. Occlusion of any form of topical therapy may enhance efficacy and side effects. Pulse dosing can be used to minimize these side effects by alternating days of application with several days off. A common example is to apply Monday to Friday and omit the weekend.

Phototherapy. Narrow-band UVB (NBUVB) and psoralen with UVA (PUVA) have been shown to be effective treatment for vitiligo; however, the exact mechanism of action is unknown. The primary objective is to stimulate the few remaining melanocytes which reside in the hair follicle. Ultraviolet light (UVL) activates the melanocytes, which migrate up the hair follicle and then spread to the surrounding area. Initially, repigmentation occurs at the hair follicle and presents as small hyperpigmented dots within the area of depigmentation.

Phototherapy can be inconvenient for the patient, however, as it is an in-office therapy usually recommended two to three times per week.

Excimer laser treatment may also be used for localized lesions twice weekly for 24 to 48 sessions.

Topical immunomodulators (TIMS). Off-label use of pimecrolimus (Elidel) and tacrolimus 0.3% to 0.1% (Protopic) is an alternative to TCS and has been effective in treating facial vitiligo. Some studies have shown that these drugs are more efficacious when used in combination with NBUVB phototherapy (Bolognia, Jorizzo, & Rapini, 2008). However, TIMS should not be on the skin while the patient is receiving a phototherapy treatment. The FDA has issued a “black-box” warning for pimecrolimus and tacrolimus, stating that they may increase the risk of lymphoma and skin cancers. Please see chapter 3 for details.

Calcipotriol. Topical calcipotriol has also proven to be effective in producing repigmentation of vitiligo when used in combination with corticosteroids. This has been observed in patients who have previously failed topical corticosteroid treatment as a monotherapy.

In general, Cochrane review states that most of the trials assessed combination therapies using phototherapy to enhance repigmentation.

Total depigmentation. Depigmentation is usually reserved for vitiligo patients with a 40% or greater BSA involvement. The treatment approach considers that it is easier to remove the remaining normal pigment to match the large depigmented areas. This is permanent and requires lifelong sun protection. A 20% cream of monobenzylether of hydroquinone may be applied b.i.d. for 6 to 18 months.

Systemic therapy. Systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are not commonly used in the treatment of vitiligo. They should only be used to arrest rapidly spreading disease.

Micropigmentation. Medical tattooing or micropigmentation may be useful for sites that have a poor response to treatment such as the lips and distal fingers.

Surgical therapies. Punch grafting may be successful for carefully chosen individuals who fail to respond to other therapies. Small punch grafts (1–2 mm) are taken from uninvolved skin and implanted 5 to 8 mm apart into the depigmented areas. Criteria for punch grafting include stable vitiligo for at least 6 months, no Koebner phenomenon, no tendency to develop keloid scars, a positive mini-grafting test, and at least 12 years of age (Bolognia et al., 2008).

Special considerations

Pediatrics. Pigment loss in children is either congenital or acquired; therefore, the onset of the disease can provide important diagnostic clues. Congenital depigmentation is an uncommon occurrence that presents at birth or during infancy and is usually associated with a genetic disorder. A white forelock on an infant would be concerning for autosomal dominant piebaldism in comparison to patients with vitiligo that may develop a forelock later in life. Children have a higher propensity for autoimmune disease than adults.

Pregnancy. Corticosteroids, pimecrolimus, tacrolimus, calcipotriol, monobenzone, and psoralens are pregnancy category C. It is best to postpone topical vitiligo treatment until after pregnancy. NBUVB treatment is safe during pregnancy.

Prognosis and complications

Treatment of vitiligo is challenging, unpredictable, and often very frustrating. Any therapy used in the treatment of vitiligo should be accompanied by the warning that lesions may not resolve and can recur. If the patient does respond to treatment, it is usually very slowly and improvement may depend on anatomic location. Facial lesions achieve greater than 90% improvement in pigmentation with TCS, whereas lesions located on the trunk only achieve a 40% response to treatment.

Repigmentation of facial lesions occurs diffusely, but it occurs perifollicularly in lesions on the trunk. Darker skin tones are more responsive to TCS than lighter skin. Cochrane review also states that none of the studies reported long-term benefit, that is, sustained repigmentation for at least 2 years.

Referral and consultation

Referral to dermatology should be made if vitiligo fails to respond to topical treatment or expands to involve large BSA as the patient may require advanced therapies. Newly diagnosed patients should be advised to have an ophthalmologic examination as there has been some association with uveitis and vitiligo. Newborns and infants with depigmented skin should be referred immediately to a pediatric dermatologist, if available. Lastly, vitiligo can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life and social development due to disfigurement. A referral to a mental health professional may be helpful.

Patient education and follow-up

Patients should be counseled on their increased risk for skin cancer and the importance of UVR protection. A broad-spectrum sunscreen containing zinc oxide or titanium dioxide should be worn and sun-protective clothing encouraged (see chapter 2). As many patients will be using TCS at some point during the treatment of their disease, the potential side effects should always be explained to the patient.

Patients should be closely monitored for efficacy and side effects of treatment. As the risk of skin cancer is increased in fair-skinned individuals with vitiligo, a thorough skin examination should be performed annually. Treated areas should be checked for pigmented macules at the site of hair follicles at each visit. Lack of improvement may be discouraging to the patient. It is important to be empathetic and understand the psychological impact that this disease has on the patient. Vitiligo can be especially disfiguring for dark-skinned individuals and children.

Pityriasis Alba

Pityriasis alba is a common dermatosis in which patients present with ill-defined patches of hypopigmentation. It is most commonly seen in children and adolescents who have a history of atopy. Males and females are affected equally. Like vitiligo, it is more cosmetically distressing for those with darkly pigmented skin.

Pathophysiology

The exact etiology of pityriasis alba is unknown, but the cause of hypopigmentation has been classified as postinflammatory. It seems to appear after a flare of eczema or atopic dermatitis. The hypopigmentation resolves spontaneously, usually before young adulthood. Histopathology reveals a reduction in the number of melanocytes.

Clinical presentation

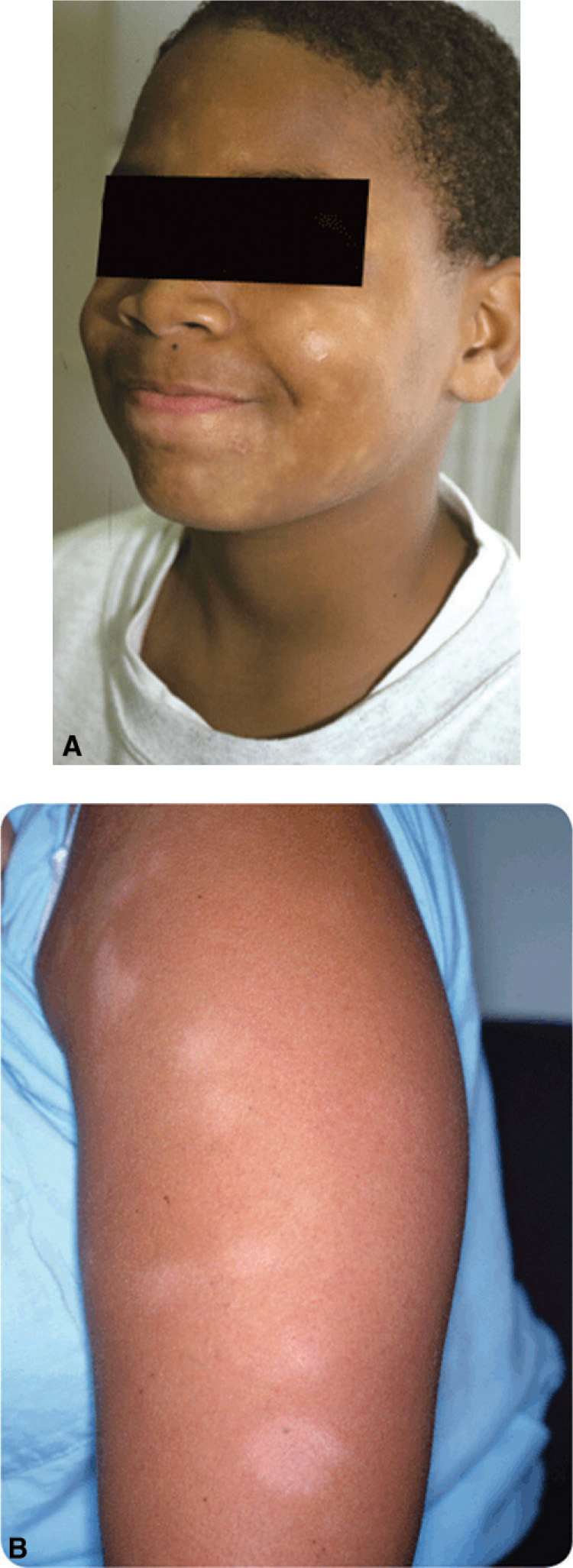

Patients with pityriasis alba are asymptomatic. Small, slightly elevated, hypopigmented, ill-defined patches are most commonly distributed on the cheeks but may also appear on the proximal upper and lower extremities. In the early stage of pityriasis alba, lesions may be mildly erythematous, then become hypopigmented and scaly. The lesions are more apparent on unaffected skin that has been tanned, creating an even greater contrast next to the hypopigmentation patches (Figure 18-4).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Pityriasis alba

• Vitiligo

• Chemical leukoderma

• Tinea versicolor

• Eczematous dermatitis

FIG. 18-4. A: Pityriasis alba on the face. B: Pityriasis alba on the arm.

Diagnostics

A negative KOH prep can differentiate pityriasis alba from tinea versicolor. In pityriasis alba, nondiscrete lesions can be visualized with wood’s lamp examination. Some melanin is present, so there is no accentuation of the color as is seen in the markedly depigmented lesions observed in vitiligo.

Management

Emollients are effective at reducing scale. Mild TCS or TIMS may be helpful, as they can reduce subtle inflammation allowing repigmentation to occur. Phototherapy has not shown an improvement in pigmentation.

Prognosis and complications

Pityriasis alba is a benign hypopigmented skin condition that resolves spontaneously. It can have psychosocial impact on darkly skinned individuals, as lesions are more noticeable.

Referral and consultation

Refer to dermatology if the pityriasis alba fails to resolve spontaneously or spreads. A referral is also warranted if the patient’s atopic dermatitis is poorly controlled.

Patient education and follow-up

It is important to listen to patients’ concerns, be empathetic, and reassure them that the hypopigmentation will resolve. Sun protection should be encouraged, as tanning may make hypopigmentation more noticeable. Patients should be educated on the proper use of emollients. If they are being treated with TCS, the side effects and risks should be discussed.

Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH) is a common dermatosis of unknown etiology. It consists of photo-distributed, hypopigmented macules on the upper and lower extremities. It affects 50% to 70% of people over the age of 50, and 80% of patients over the age of 70. It seems to be more common in females, perhaps because females seek medical attention more frequently than men.

Pathophysiology

Histopathology shows a loss of melanocytes in the skin, but not a complete absence. Some melanocytes function normally, while others do not. This is thought to be a result of actinic damage, as patients exhibit signs of photoaging in the same locations. Others propose that it is a degenerative sign of aging.

Clinical presentation

Patients usually present with IGH out of cosmetic concern. There are well-circumscribed, 2- to 5-mm, hypopigmented macules distributed on the sun-exposed (extensor) surfaces of the upper and lower extremities. Lentigines and xerosis are typically present. Once these hypopigmented macules present, they do not usually become larger and are permanent (Figure 18-5).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis |

• Pityriasis alba

• Vitiligo

• Tinea versicolor

• Flat warts

FIG. 18-5. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis.

Diagnostics

IGH is usually a clinical diagnosis. A skin biopsy is not usually needed, but may confirm an incomplete loss of melanocytes and melanin. A KOH prep may be done if tinea versicolor is suspected.

Management

The patient should be reassured that this is a benign skin finding. There have been some reports that liquid nitrogen has caused repigmentation. Cryotherapy may cause leukoderma or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, so patients should be well aware of this risk. Tinted makeup, such as Dermablend or Covermark, can be used to cover hypopigmented macules. Self-tanners are not helpful as the macules do not absorb the topical.

Prognosis and complications

Patients tend to develop more lesions as they age; however, the size of the lesions should remain stable. Future sun exposure or tanning may darken the surrounding area and accentuate the appearance of the hypopigmented macules.

Patient education and follow-up

Patients should be reassured that treatment is not medically necessary as it is a benign condition. They should be counseled on sun protection.

Follow-up is generally not needed; however, these patients often have significant actinic damage, so careful skin cancer screening should be performed.

DISORDERS OF PIGMENT EXCESS

Melasma

Melasma, also known as chloasma or the mask of pregnancy, is a common disorder of hyperpigmentation. Melasma is more common in females of childbearing age, and those with darker skin phenotypes. Genetics is suspected to play a role in melasma in Asian and Hispanic ethnicities. Sun exposure is the greatest risk factor for the development of melasma, and hormones have also been implicated. Therefore, pregnant women and those taking oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy are at higher risk.

Pathophysiology

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree