Concerns for the cosmetic surgeon regarding allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and rhinosinusitis include diagnosis, treatment, and assessment of the disease and whether or not the timing or outcome of cosmetic procedures will be affected. In this article, the pharmacotherapy of allergic and nonallergic rhinoconjunctivitis and rhinosinusitis is discussed with emphasis on intranasal steroids, antihistamines, and antibiotics.

- •

Intranasal corticosteroids (INCS) are an effective first-line treatment of allergic rhinitis.

- •

INCS are more effective than oral antihistamines or leukotriene receptor antagonists for the treatment of allergic rhinitis.

- •

Intranasal antihistamines are effective for nasal congestion and some types of nonallergic rhinitis.

- •

Most oral antihistamines control all the nasal symptoms of rhinitis except nasal congestion.

- •

Topical antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, or combinations are useful for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (ARC).

- •

Ocular itching is the pathognomonic sign of ARC.

- •

The most common bacteria isolated from the maxillary sinuses of patients with acute bacterial rhinosinusitis include Streptococcus pneumoniae , Haemophilus influenzae , and Moraxella catarrhalis.

- •

Most guidelines recommend amoxicillin as first-line therapy for the treatment of acute rhinosinusitis because of its safety, effectiveness, low cost, and narrow microbiological spectrum.

- •

A 2009 Cochrane review suggested the use of INCS as a monotherapy or as an adjunct to antibiotics for patients with acute rhinosinusitis.

- •

Cosmetic surgery in patients with inflammation due to ARC, acute rhinosinusitis, or chronic rhinosinusitis may be performed if treatment, avoidance, or timing is used to reduce inflammation.

Symptomatic allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (ARC) affects around 20% of adults in the United States. A nationwide survey in 2006 showed that 54.6% of people in the United States tested positive for at least 1 allergen. Allergic disorders can affect all portions of the respiratory tree, including the nose, and commonly affect the eyes as well. Concerns for the cosmetic surgeon relative to allergic disorders include diagnosis, treatment, and assessment of the disease and whether or not therapy may affect the timing or outcome of cosmetic procedures. In this article, the pharmacotherapy of allergic and nonallergic rhinoconjunctivitis and rhinosinusitis is discussed. Although rhinitis and conjunctivitis may both occur without IgE-mediated allergy, it is the most common mechanism. Rhinosinusitis, both acute and chronic, involves inflammation, which may be reduced with antiinflammatory therapies.

Pathophysiology of ARC

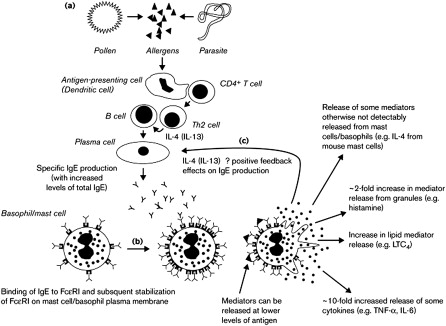

Allergen sensitization in the nose starts with the interaction of the antigen-presenting cell with the T helper cell. On deposition of the allergen in a susceptible host, the interaction results in IgE production ( Fig. 1 ). This IgE response is the pathophysiologic basis of allergic rhinitis, and it includes both early and late phases. The most important cell mediating the early response is the mast cell. Cross-linkage of membrane-bound IgE triggers mast cell degranulation, releasing histamine and a cascade of allergic and inflammatory mediators. During the early phase, there may be symptoms of itchiness, rhinorrhea, and sneezing. In the late phase, B cells (T cells and basophils) are recruited. The presence of these cells results in an increase in production of allergen-specific IgE and increased hyperresponsiveness to the allergen.

Diagnosis of rhinitis

History

Documenting the patient’s history is the most important first step. The patient should be encouraged to describe specific symptoms, such as sneezing, itchy eyes, and nasal blockage. Common allergic symptoms include nasal blockage/congestion; rhinorrhea (anterior and posterior); paranasal pain or headache; sneezing; pruritus; itchy, watery, or red eyes; anosmia; dysosmia; chronic pharyngitis; and hoarseness. Symptoms may occur perennially from dust mites, molds, cockroaches, cats, or dogs and/or seasonally from trees, grasses, weeds, and seasonal molds.

Patients with allergy generally have many concurrent symptoms. It is important to ask the patient to focus on what is most bothersome and choose the 3 to 4 most prominent symptoms, such as nasal congestion, itchy eyes, sneezing, and red eyes.

Physicians should document the factors that worsen symptoms, such as windy days for pollen or visits to a home with pets; medications being used, both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC); and the patient’s response or lack of response to the treatments. It should be noted that many allergy medications are available OTC at present, and most patients have tried at least OTC treatment or received a prescription from their primary care physician. A family history of documented allergy can be an important clue that current symptoms may be caused by allergy. It is also important to ask about other related health issues, including atopic disorders such as eczema, food allergy and uriticaria.

Physical Examination

Initial examination can show classic signs of allergy, such as “boggy” bluish nasal mucosa, red inflamed nasal mucosa, or excessive clear watery mucus. In the eyes, dark skin of the lower eyelids (allergic shiners), periorbital and/or conjunctival erythema, and edema may be present.

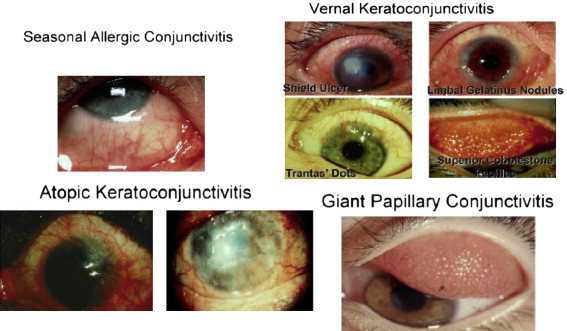

Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis represent most cases of ocular allergy, whereas the more severe conditions of atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) affect a smaller group of patients. Fig. 2 shows photographs of eyes from individuals with the various forms of allergic conjunctivitis. Allergic conjunctivitis is typically elicited by ocular exposure to allergen. Despite differences in disease classification and incidence, the allergic response in conjunctivitis is similar to the pathophysiology of allergic rhinitis. The pathognomonic symptom of ocular allergy is itching. Most patients with allergic rhinitis also have eye symptoms.

Testing

Various testing methods are used for allergic disorders, including skin prick, intradermal testing, serial dilution titration, and in vitro allergy tests. Practitioners who do not practice immunotherapy in their office may wish to confirm diagnoses through in vitro testing for allergen-specific IgE of common allergens after a trial of appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Diagnosis of rhinitis

History

Documenting the patient’s history is the most important first step. The patient should be encouraged to describe specific symptoms, such as sneezing, itchy eyes, and nasal blockage. Common allergic symptoms include nasal blockage/congestion; rhinorrhea (anterior and posterior); paranasal pain or headache; sneezing; pruritus; itchy, watery, or red eyes; anosmia; dysosmia; chronic pharyngitis; and hoarseness. Symptoms may occur perennially from dust mites, molds, cockroaches, cats, or dogs and/or seasonally from trees, grasses, weeds, and seasonal molds.

Patients with allergy generally have many concurrent symptoms. It is important to ask the patient to focus on what is most bothersome and choose the 3 to 4 most prominent symptoms, such as nasal congestion, itchy eyes, sneezing, and red eyes.

Physicians should document the factors that worsen symptoms, such as windy days for pollen or visits to a home with pets; medications being used, both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC); and the patient’s response or lack of response to the treatments. It should be noted that many allergy medications are available OTC at present, and most patients have tried at least OTC treatment or received a prescription from their primary care physician. A family history of documented allergy can be an important clue that current symptoms may be caused by allergy. It is also important to ask about other related health issues, including atopic disorders such as eczema, food allergy and uriticaria.

Physical Examination

Initial examination can show classic signs of allergy, such as “boggy” bluish nasal mucosa, red inflamed nasal mucosa, or excessive clear watery mucus. In the eyes, dark skin of the lower eyelids (allergic shiners), periorbital and/or conjunctival erythema, and edema may be present.

Seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis represent most cases of ocular allergy, whereas the more severe conditions of atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) affect a smaller group of patients. Fig. 2 shows photographs of eyes from individuals with the various forms of allergic conjunctivitis. Allergic conjunctivitis is typically elicited by ocular exposure to allergen. Despite differences in disease classification and incidence, the allergic response in conjunctivitis is similar to the pathophysiology of allergic rhinitis. The pathognomonic symptom of ocular allergy is itching. Most patients with allergic rhinitis also have eye symptoms.

Testing

Various testing methods are used for allergic disorders, including skin prick, intradermal testing, serial dilution titration, and in vitro allergy tests. Practitioners who do not practice immunotherapy in their office may wish to confirm diagnoses through in vitro testing for allergen-specific IgE of common allergens after a trial of appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Treatment options for rhinitis and rhinosinusitis

There are multiple types of treatments for ARC, including avoidance of known initiating triggers, pharmacotherapy, and immunotherapy. However, the only treatment that has been shown to alter the natural history of this disease is immunotherapy. In this article, the treatment is discussed in 3 broad categories: avoidance, pharmacotherapy, and immunotherapy. Allergic conjunctivitis is treated similarly, although immunotherapy is rarely indicated for allergic conjunctivitis alone.

Avoidance

Patients with ARC may benefit from avoiding inciting factors, effectively reducing symptoms. It may be difficult for patients to comply with the recommendations because they may interfere with their daily life activities. Patients allergic to house dust mites can use allergen-impermeable encasings on the bed and pillows. Pollen exposure can be reduced by keeping windows closed, using an air conditioner, and limiting the amount of time spent outdoors. Avoiding basements and reducing household humidity is important in patients who have mold allergy. Filtration systems, including high-efficiency particulate air filters, may be used to aid in decreasing the allergen load. Patients who are allergic to pets should avoid having pets in the house or at least in their bedroom. The effectiveness of avoidance measures may be small because of the ubiquity of inhalant allergens. However, reports of individual patient responses vary, and the diligent use of multiple avoidance measures simultaneously with medical therapy can be beneficial.

Pharmacotherapy of allergic rhinitis

Symptoms may be generally divided into 2 broad categories: runners and blockers. Runners complain of rhinorrhea; sneezing; itchy nose, eyes, and throat; and red eyes. These symptoms are related mostly to early-phase mediators, such as histamine, and respond well to oral or intranasal antihistamines and steroids. Blockers usually complain of nasal congestion and benefit from intranasal steroids, leukotriene inhibitors, and intranasal antihistamines.

There are 2 broad categories of pharmacologic treatments for patients with allergic rhinitis. The targeted forms of treatment are drugs that act on the mediators of the mast cell, whereas immunomodulatory therapies prevent initiation and/or downregulate the immunologic response.

Targeted therapies include decongestants, antihistamines, anticholinergics, leukotriene inhibitors, and mast cell stabilizers. Immunomodulators include mast cell stabilizers, leukotriene inhibitors, steroids (oral, intranasal, ophthalmic, or depot injection), and allergen-specific IgE treatment (either subcutaneous or sublingual) or anti-IgE injection (omalizumab).

Intranasal Corticosteroids

The mainstay of treatment of allergic rhinitis is intranasal corticosteroids (INCS). Their mechanism of action is to inhibit the release of cytokines, decrease inflammatory cells, and reduce inflammation of the nasal mucosa. Steroids have an onset of action of about 30 minutes, with their peak effect taking hours to days and their maximum effect usually taking 2 to 4 weeks.

Initial indications for INCS included second-line or add-on treatment of ARC. New data show that INCS are more effective than oral or intranasal antihistamines for the treatment of allergic rhinitis, justifying first-line treatment. Table 1 shows a list of some of the commonly used intranasal steroids with their brand names and potential side effects, which include bitter aftertaste, burning, epistaxis, headache, nasal dryness, potential risk of systemic absorption, rhinitis medicamentosa, stinging, and throat irritation.

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Beclomethasone | Beconase | 1–2 puffs each side, bid |

| Budesonide | Rhinocort | 1–4 puffs each side, qd |

| Ciclesonide | Omnaris | 1–2 puffs each side, qd |

| Fluticasone propionate | Flonase a | 1–2 puffs each side, qd |

| Fluticasone furoate | Veramyst | 1–2 puffs each side, qd |

| Mometasone | Nasonex | 1–2 puffs each side, qd |

| Triamcinolone | Nasacort | 1–2 puffs each side, qd |

The potential for cataract formation and glaucoma may be a concern for the cosmetic surgeon. Current literature indicates that there is very little evidence of an association between INCS and glaucoma or cataract formation. There is no evidence in the literature to support the usage of any particular INCS because they have not been shown to be different except for their age indications in accordance with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Oral and Topical Antihistamines

Antihistamines can be used for the treatment of ARC. They can be used as oral or topical treatments. Oral antihistamines include first-generation and second-generation antihistamines. The first-generation antihistamines are more lipid soluble and are able to cross the blood-brain barrier more readily than those of the second generation. For this reason, first-generation antihistamines have been associated with adverse effects, including, but not limited to, sedation, fatigue, impaired mental status, poor school performance, impaired driving, and increase in automobile collisions and work-related injuries. Common first-generation and second-generation oral antihistamines are listed in Table 2 . Most second-generation antihistamines have a more complex chemical structure, thus decreasing their capability to cross the blood-brain barrier. For this reason, most second-generation antihistamines have very low sedation potential and central nervous system side effects, and are therefore considered nonsedating. Oral cetirizine and oral levocetirizine, intranasal azelastine, and intranasal olopatadine have a lower sedation potential than first-generation antihistamines but are not classified as nonsedating. Most oral antihistamines control nasal and ocular symptoms with minimal effect on nasal congestion, with the exception of desloratadine. Because of their rapid onset of action (between 15 and 30 minutes) and their safety for use in children older than 6 months, antihistamines are frequently used for mild symptoms requiring as-needed treatment.

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| First generation | ||

| Dexchlorpheniramine a | Polaramine | 2 mg po q 4–6 h |

| Diphenhydramine a | Benadryl | 25 mg po q 4–6 h |

| Hydroxyzine | Atarax | 25–100 mg po q 4–8 h |

| Promethazine | Phenergan | 12.5–25 mg po q 6–24 h |

| Second generation | ||

| Cetirizine a | Zyrtec | 5–10 mg po qd |

| Desloratadine | Clarinex | 5 mg po qd |

| Fexofenadine a | Allegra | 180 mg po qd or 60 mg po bid |

| Levocetirizine | Xyzal | 5 mg po qd |

| Loratadine a | Claritin | 10 mg po qd |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree