Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis): Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) is the least common, yet best-characterized, dermatitis specific to pregnancy.1 It classically presents as an intensely pruritic, urticarial rash during the later part of pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period, then rapidly progresses to a pemphigoid-like, vesiculobullous eruption. The rash may wax and wane during pregnancy, only to flare during labor and delivery. PG appears to be mediated by a specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G directed against the cutaneous basement membrane zone (BMZ).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

PG appears to be caused by an anti-BMZ antibody that induces C3 deposition along the dermal–epidermal junction. The PG autoantibody (formerly called HG factor) is an IgG that is infrequently found by direct immunofluorescence (IF), although indirect, complement-added IF reveals the circulating IgG in the majority of patients. In salt-split skin, staining remains with the epidermal fragment. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the PG antibody is commercially available, and when this highly sensitive test is used, antibody titers appear to correlate with disease activity.5 The PG autoantibody appears to belong to the IgG1 subclass and fixes complement via the classical complement pathway.6 T cells also show selective NC16A reactivity in PG, although their role in disease development remains to be elucidated.7

Nearly all patients with PG [and most patients with bullous pemphigoid (BP)] have demonstrable antibodies to BP180 (type XVII collagen), a 180-kDa transmembrane protein with its N-terminal end embedded within the intracellular component of the hemidesmosome and its C-terminal end located extracellularly (see Chapter 53). The extracellular section contains a series of 15 collagenous components alternating with 16 short, noncollagenous domains. The sixteenth noncollagenous segment closest to the plasma membrane of the basal keratinocyte is designated NC16A and contains the BP180 immunoreactive site.8,9 The PG autoantibody is assumed to be pathogenic for several reasons: (1) It is found in essentially all patients. (2) In vitro, purified antibodies to BP180 cause chemoattraction to the dermal–epidermal junction with subsequent degranulation and dermal–epidermal separation.10 (3) BP180 antibodies cause keratinocytes to lose cell adhesion in tissue culture.11 (4) Rabbit antibodies to BP180 in animal models induce subepidermal blisters when infused into neonatal mice or hamsters.12,13

The BP180 protein differs significantly from the BP230 protein recognized by the majority of BP sera.14,15 The 230-kDa protein is coded for on the short arm of chromosome 6.16 Its complementary DNA (cDNA) has been sequenced17 and codes for an intracellular protein18 that shows considerable homology with desmoplakin I.19 The 180-kDa protein is coded on the long arm of chromosome 10.20 Its cDNA shows no homology with the 230-kDa cDNA but rather encodes a protein with two domains showing the primary structure of trihelical collagen.21

What initiates the production of autoantibody remains unclear, but because gestational pemphigoid is exclusively a disease of pregnancy, attention has focused on immunogenetics and the potential for cross-reactivity between placental tissue and skin.

Immunogenetic studies reveal an increase in HLA antigens DR3 or DR4, and curiously, nearly 50% of patients have the simultaneous presence of both.22 The extended haplotype HLA-A1, B8, DR3 is known to be in linkage disequilibrium with a deletion of C4A (the C4 null allele or C4QO). Indeed, 90% of patients have either a C4AQO or a C4BQO.23 However, whether the C4QO association is the primary genetic marker for PG or the presence of a C4QO is even clinically relevant to complement function remains to be shown.

It is worth noting that patients with neither DR3 nor DR4 may have disease clinically indistinguishable from those with classic HLA findings; the presence of HLA-DR3, -DR4, or the concurrent presence of both is neither necessary nor sufficient to produce disease.22

Essentially, 100% of women with a history of PG have demonstrable anti-HLA antibodies.24,25 Because the only source of disparate HLA antigens is typically the placenta (which is primarily of paternal origin), the universal finding of anti-HLA antibodies implies a high frequency of immunologic insult during gestation. Indeed, a slight increase in HLA-DR2 in the husbands of women with PG has been reported.24 It has been suggested that immunologically primed women may simply react more strongly to tissue with disparate HLA antigens. Whether anti-HLA antibodies represent phenomenon or epiphenomenon remains to be clarified.

The autoantibody of gestational pemphigoid binds to amniotic basement membrane, a structure derived from fetal ectoderm and antigenically similar to skin.26,27 Women with PG also show an increased expression of major histocompatibility complex class II antigens (DR, DP, DQ) within the villous stroma of chorionic villi but not skin.28,29 Therefore, it has been proposed that PG is a disease initiated by the aberrant expression of major histocompatibility complex class II antigens (of paternal haplotype) within the placenta that serves to initiate an allogeneic response to placental BMZ, which then cross-reacts with skin.30

On the other hand, PG has also been reported in association with hydatidiform moles31 and choriocarcinomas.32 This is an intriguing clinical observation, because most hydatidiform moles are produced by a diploid contribution of paternal chromosomes and contain neither fetal tissue nor amnion. There are no case reports of a PG-like rash in males with choriocarcinoma. Unlike its counterpart in women, choriocarcinoma in males is strictly syngeneic tissue. Because choriocarcinoma in women is entirely derived from placental tissue (of paternal derivation), the suggestion is that the development of PG is somehow dependent on the state of partial allograph, not necessarily on the presence of amnion.

Clinical Findings

PG is exclusively associated with pregnancy. It typically presents during late pregnancy with the abrupt onset of intensely pruritic urticarial lesions. Fifty percent of patients experience first onset on the abdomen, often within or immediately adjacent to the umbilicus. The other half present with typical lesions, but in an atypical distribution (extremities, palms, or soles). Rapid progression to a generalized, pemphigoid-like eruption, sparing only the face, mucous membranes, palms, and soles is the rule (although any site may be involved). Flares occur with delivery in approximately 75% of patients and may be dramatic. The explosive onset of blistering may occur within hours of delivery, either as a flare of preexisting disease or as presentation de novo. Up to one-quarter of patients initially present during the immediate postpartum period.

Newborns may be affected up to 10% of the time, but the disease is typically mild and self-limited. IF of newborn skin may yield positive findings despite a lack of clinically apparent disease, which suggests that more than C3 deposition alone is required to induce lesions.33

Because of clinical and IF similarities with BP, and because of the considerable confusion over the term herpes gestationis (particularly outside dermatology), most authors have accepted the revised terminology of PG.34 However, there are several differences worth bearing in mind: (1) BP is a disease of the elderly and shows no gender bias. PG is exclusively associated with pregnancy. (2) PG shows a strong association with HLA-DR3, -DR4, and a C4 null allele. BP does not. (3) Indirect IF in BP yields positive results in the majority of patients, and the titer of anti-BMZ antibody is often high. The titer of anti-BMZ antibody in PG is usually so low that antibody cannot be detected without the use of complement-added or ELISA techniques. (4) The majority of BP sera react to an intracellular 230- to 240-kDa component of the hemidesmosome. Sera from most PG patients react to a 180-kDa transmembrane protein with a collagenous domain coded for on a different chromosome. Until such time as nosology is driven by pathologic mechanism instead of clinical observation, naming is likely to remain fungible.

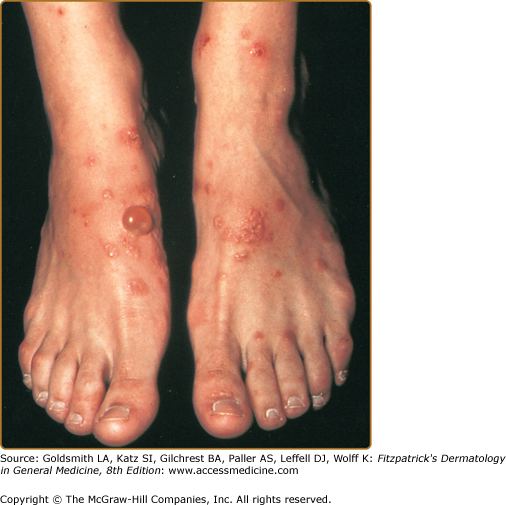

The typical lesions of PG are urticarial or arcuate plaques that rapidly progress toward a mixed dermatitis, including tense, pemphigoid-like blisters (Figs. 59-1 and 59-2, and eFig. 59-2.1). Blisters may arise within urticarial plaques or on otherwise normal-appearing skin. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (see Chapter 108) can show microvesiculation but not the tense, subepidermal blisters of PG.