CUTANEOUS DISORDERS OF THE NEWBORN

Newborn skin is different from adult skin in several ways: It is thinner, less hairy, and the attachment between the epidermis and dermis is weaker. Infants have a body surface area to weight ratio that is up to five times higher than adults. For these reasons, infant skin is at a higher risk for injury, percutaneous absorption, and skin infection. Additionally, infants have a higher rate of transepidermal water loss, which can lead to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and temperature instability.

NEWBORN SKIN CARE

At birth, the skin is covered with vernix caseosa, a grayish-white thick greasy material. Newborns lack the normal skin flora that protects against infection. There may be one or two surgical wounds present after birth—the umbilical stump and the circumcision site. To prevent infection, skin care should involve gentle cleansing with nontoxic, nonabrasive material. Wipe the vernix caseosa from the face, but allow the vernix on the rest of the body to come off by itself.

Newborns do not need to be bathed daily. Washing the buttocks and perianal area with warm soapy water at diaper changes will suffice. Once weekly bathing should be quick, to prevent thermoregulatory problems, followed by application of topical emollients to prevent transepidermal water loss and improve barrier function. Safe ingredients for neonates include white petrolatum ointment and lanolin. Parents should look for products that are fragrance- and dye-free.

There is no single standard of care for the umbilical stump. Avoid the use of povidone-iodine, as absorption of iodine can cause transient hypothyroxinemia or hypothyroidism. The cord site can be left dry, without bandages until the crust falls off on its own, usually about 10 days after birth. The site can become irritated, red, and sometimes painful, usually from diapers or clothing rubbing or pulling on the scab.

Infection of the umbilical stump is not common but can occur and may present as periumbilical erythema and induration (omphalitis). Staphylococcus aureus, introduced through the cut umbilical stump, is the most common pathogen and requires treatment to prevent sepsis. Systemic antibiotics are first line, but preventing infection is the primary focus. Daily washing with regular soap and water is usually enough to prevent infection.

Care of the circumcision site is similar to that of the umbilical stump. Keep the area clean by washing the area gently with soap and water at least once a day. Apply petrolatum ointment to the tip of the penis at each diaper change to prevent the penis from sticking to the diaper. The penis may initially be red, swollen, and bruised, and can have an yellow crust. Infection is rare; perform a culture if there is pus or drainage. The wound will heal in about 7 to 10 days.

SUBCUTANEOUS FAT NECROSIS

Subcutaneous fat necrosis (SCFN) is a benign panniculitis that affects healthy full-term newborns. It usually begins during the first few days to weeks of life.

Pathophysiology

The cause is unknown. It may be related to perinatal trauma, asphyxia, hypothermia, and hypercalcemia.

Clinical Presentation

SCFN is usually painless, but occasionally can be tender or uncomfortable, making infants cry when handled. There may be one or several erythematous or bruise-like, well-defined, firm nodules or large plaques, but they are not warm to touch. SCFN occurs most often on the cheeks, back, buttocks, arms, and thighs (Figure 6-1).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Subcutaneous fat necrosis |

• Cellulitis

• Erysipelas

• Sclerema neonatorum

• Nevus comedonicus

• Child abuse

Diagnostics

A punch biopsy of affected skin will confirm the diagnosis. This diagnosis can sometimes be made clinically. Serum calcium should be evaluated.

Management

Hypercalcemia is rare, but can be treated with low calcium and vitamin D intake or systemic corticosteroid therapy.

FIG. 6-1. Superficial red nodules of varying size due to subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Prognosis and Complications

SCFN is self-limited. Most lesions heal spontaneously, though lesions can become fluctuant with necrotic fat, ulcerate, and scar. Some heal with temporary skin depression, which resolves over time without treatment.

Referral and Consultation

Dermatology should be consulted. In severe or ulcerated cases, a surgical consultation may be required for debridement.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Parents should be reassured that most cases of SCFN spontaneously resolve without significant sequelae. If hypercalcemia is present, serum calcium levels should be monitored regularly and patients placed on a low calcium and vitamin D diet.

MILIARIA

Miliaria crystallina and miliaria rubra (prickly heat) commonly occur in infancy. The onset of miliaria crystallina peaks at one week of life. Miliaria rubra can present in infants and adults, and usually follows a move to a tropical climate.

Pathophysiology

Miliaria is caused by an occlusion of the sweat glands, resulting in retention and rupture. Crystallina occurs higher in the epidermis, at the stratum corneum, compared to rubra, which occurs deeper in the epidermis.

Clinical Presentation

Clear, superficial pinpoint vesicles without inflammation are the classic presentation of miliaria crystallina. Lesions rupture in 1 or 2 days, leaving behind a fine scale. In infants, it occurs on the head, neck, and upper trunk. In older children, it favors the sun-exposed areas. Miliaria rubra is characterized by slightly larger 2- to 4-mm erythematous papules or vesicles, and occurs after excessive sweating. These lesions tend to favor flexural areas, including the neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossae, axillae, and groin, or in localized areas that have been occluded. Rubra also tends to be quite itchy or may sting, and may last for weeks. Secondary bacterial infections can occur, changing the morphology to pustules or honey-crusted lesions.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Miliaria |

• Cutaneous candidiasis

• Varicella

• Erythema toxicum neonatorum

• Folliculitis

• Herpes simplex virus

• Pityrosporum folliculitis

• Pseudomonas folliculitis

Diagnostics

Miliaria is a clinical diagnosis. If the diagnosis is uncertain, a biopsy could be helpful. A Tzanck examination negative for multinucleated giant cells will rule out HSV and a negative KOH test eliminates a yeast or fungal etiology.

Management

Miliaria crystallina does not require treatment because it is asymptomatic and benign. Treatment of miliaria rubra includes avoiding excessive heat and humidity to minimize sweating, dressing in lightweight cotton clothing, limiting activity, taking cool baths, and using air conditioning. For infants, a mild-potency topical corticosteroid (TCS) may be used but should be limited to no more than 2 weeks. If a secondary bacterial infection has been identified by culture and sensitivity, mupirocin 2% ointment three times daily for 10 days is safe and usually effective for infants.

Referral and Consultation

If the diagnosis is unclear or the symptoms are severe, a referral to a pediatric dermatologist is warranted.

Prognosis and Complications

Miliaria crystallina is self-limited, and resolves without complications in a few days. Miliaria rubra spontaneously resolves when patients are moved to cooler environments, but will recur when sweating is stimulated.

Patient Education and Follow-up

For infants, the emphasis should be on the avoidance of over dressing. Patient education should also include avoiding high heat and humidity (above).

ACNE NEONATORUM

Acne neonatorum refers to neonatal acne and infantile acne. Neonatal acne usually begins within the first few weeks of life and resolves by 6 months of age. Infantile acne occurs in males to females 5:1, and starts at 6 to 12 months old.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of most neonatal acne is unknown, but may be related to hormonal stimulation of sebaceous glands by maternal androgens. Infantile acne, which starts later, tends to be more severe and persistent than neonatal acne, and may occasionally be associated with an underlying systemic disease or hormonal abnormality.

Clinical Presentation

Neonatal acne and infantile acne resemble acne vulgaris, with involvement usually on the face only. Open and closed comedones are most common; inflammatory papules and pustules are seen occasionally. Rarely, deep papules, nodules, and cysts can present with infantile acne. When neonatal acne is associated with Malassezia yeast overgrowth, lesions appear more pustular.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Acne neonatorum |

• Miliaria

• Rosacea

• Contact dermatitis

• Seborrheic dermatitis

• Folliculitis

Diagnostics

Direct examination of pustule contents with KOH test shows yeast. A bacterial culture and sensitivity may be indicated if there is suspicion of infection. If acne is especially severe or persistent, diagnostic tests for abnormal androgen production should be considered.

Management

Treatment is not usually needed, as most cases are mild. Neonatal acne tends to resolve spontaneously in 1 to 2 weeks. Cleansing with gentle soap and water daily can clear many cases. Mild inflammatory acne can be treated safely in patients of all ages. Topical antibiotics, such as erythromycin or clindamycin, are not recommended as monotherapy because they take a long time to start working and are associated with high rates of bacterial resistance. Instead, Eichenfield et al. (2013) recommends using benzoyl peroxide 2.5%, 5%, or 10% and clindamycin 1% in conjunction (Duac, Benzaclin, Acanya). In moderate to severe acne cases, dermatology specialists may use topical retinoids. Most are used off-label for children under 12 years old, except for combination adapalene plus benzoyl peroxide gel 0.1%/2.5% (Epiduo) which is approved for those 9 years and older. Patients with Malassezia can be treated with topical antifungal creams or shampoos, like ketoconazole 2% or selenium sulfide 2.5%.

Prognosis and Complications

Nearly all cases of acne neonatorum resolve spontaneously. Treatment may hasten resolution.

Referral and Consultation

If severe, patients should be referred to a dermatologist. Refer to endocrinologist if there are any signs of virilization or growth abnormalities.

ERYTHEMA TOXICUM NEONATORUM

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) is a benign, self-limiting eruption seen in full-term neonates. It most often begins in the first 2 to 4 days of life.

Pathophysiology

ETN is idiopathic.

Clinical Presentation

Erythematous macules and papules occur anywhere on the body, usually sparing the palms and soles. Lesions may be blotchy and irregular, and can vary in size from 1- to 3-mm papules and pustules to larger pink plaques that are several centimeters in diameter (Figure 6-2).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Erythema toxicum neonatorum |

• Transient neonatal pustular melanosis

• Milia

• Miliaria

• Candidiasis

• Herpes simplex virus

• Folliculitis

Diagnostics

ETN is a clinical diagnosis, and skin biopsy is rarely indicated.

FIG. 6-2. Erythema toxicum neonatorum.

Management

No treatment is necessary.

Prognosis and Complications

ETN is self-limiting, and patients rarely have complications.

Patient Education and Follow-up

ETN may be concerning to parents, so reassurance and parent education are important. No follow-up is necessary unless the characteristics of the eruption change.

Seborrheic Dermatitis

In children, seborrheic dermatitis is a benign, erythematous scaly or crusting dermatosis common in infants and adolescents. Parents may call it “cradle cap.”

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of seborrheic dermatitis is unknown. It occurs in “seborrheic areas” (see chapter 5) which contain the highest concentration of sebaceous glands, suggesting an association with sebum and sebaceous glands. The yeast, Malassezia furfur, has also been implicated.

Clinical Presentation

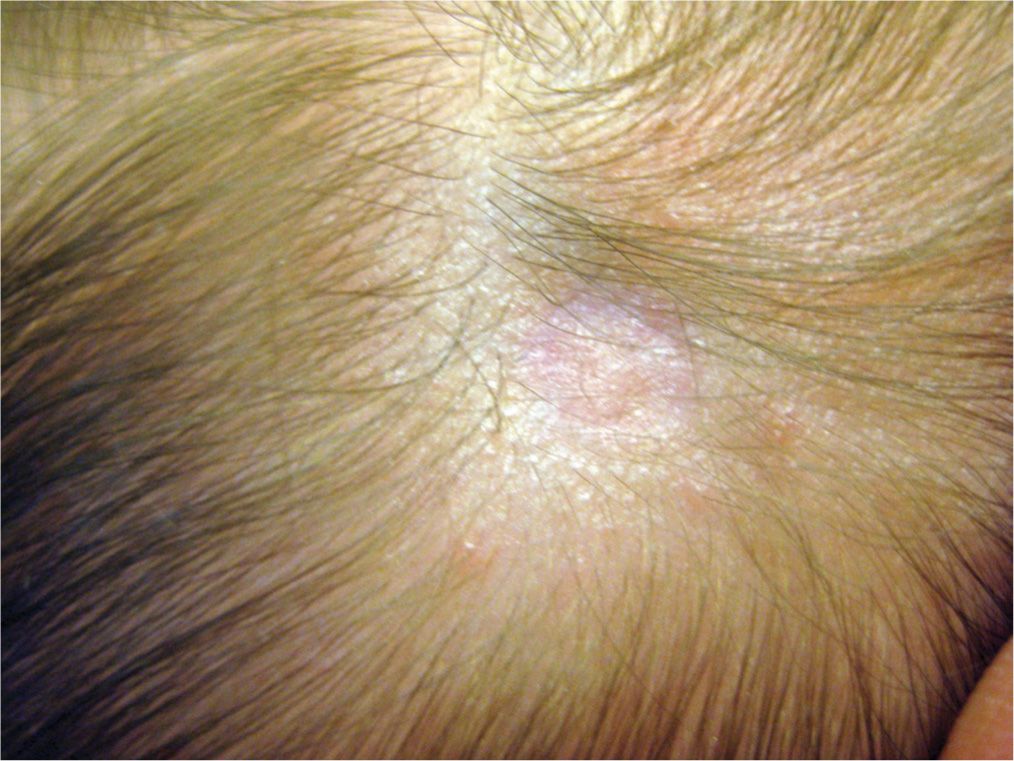

In infants, scalp involvement has variable erythema with thin, white-yellow scale (Figure 6-3). In the diaper area, lesions are redder and may have scale with accentuation in the skin folds (Figure 6-4). In older children and adolescents, central facial and nasolabial folds can have red to salmon-colored with greasy scale and sharply defined borders. Pinpoint red papules may present near the nasal ala. They may complain of dandruff. Pruritus is usually minimal.

FIG. 6-3. Seborrheic dermatitis. Note the thick yellow scale, background erythema, and typical seborrheic distribution.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Seborrheic dermatitis |

• Atopic dermatitis

• Acneiform dermatoses

• Contact dermatitis

• Psoriasis

• Langerhans cell histiocytosis

• “Leiner’s phenotype” of immunodeficiency

FIG. 6-4. Seborrheic dermatitis is most common in children and is manifested by skin fold redness and scale.

Diagnostics

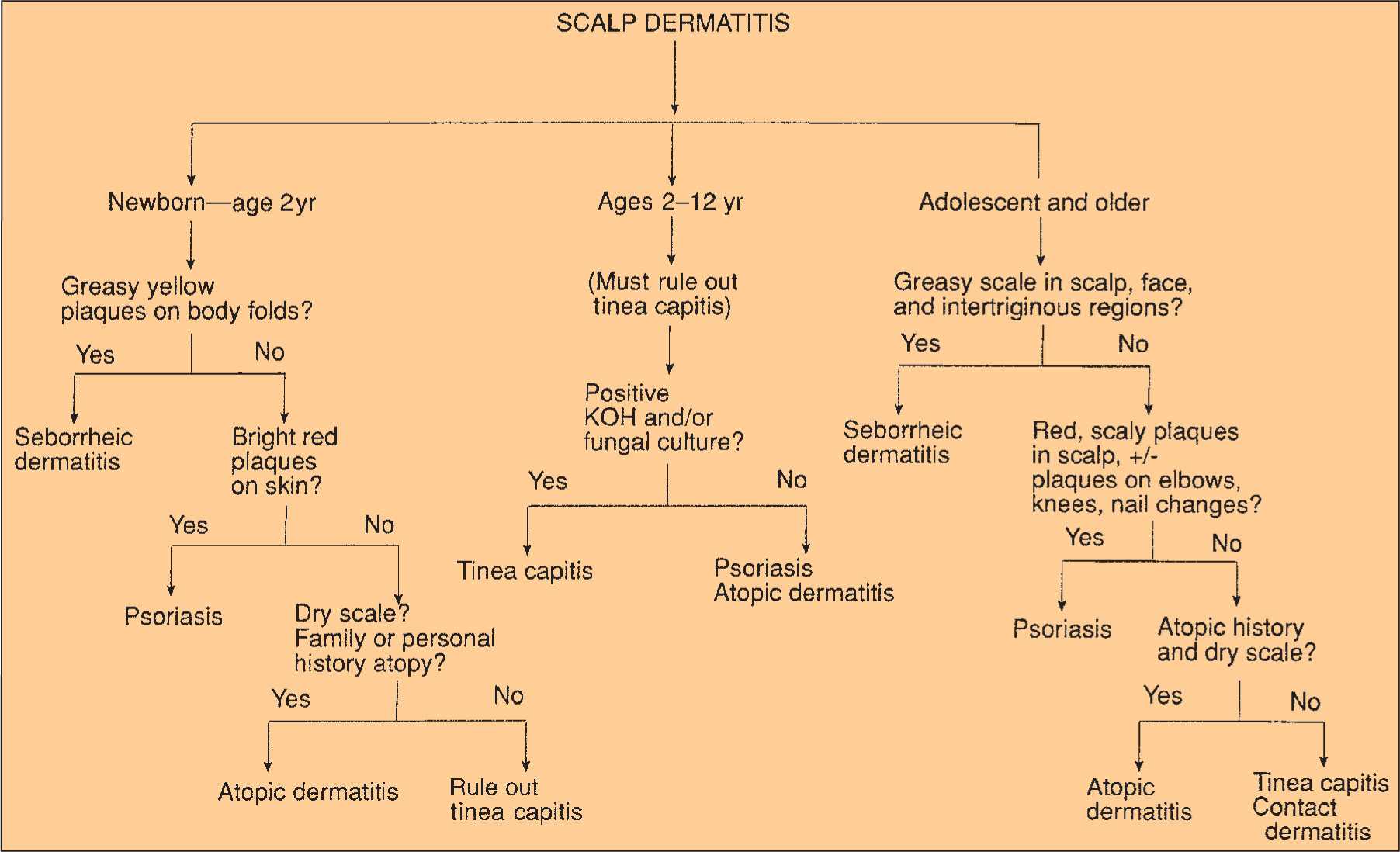

Seborrheic dermatitis is usually diagnosed clinically. However, the diagnosis can be difficult and must be differentiated from other papulosquamous, eczematous, and infectious dermatoses. If seborrheic dermatitis occurs in a child with failure to thrive and diarrhea, evaluate for immunodeficiency. Figure 6-5 shows an algorithm for use in diagnosing scaly scalp.

FIG. 6-5. Algorithm for diagnosis of a scaly scalp.

Management

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis can resolve in as little as 3 to 4 weeks, even without treatment. Therefore, because it is benign, watchful waiting and reassurance are acceptable. If treatment is desired for infants and children, application of mineral or baby oil can be left on the scalp overnight. A shampoo in the morning will allow for gentle removal of the scale with a soft brush or toothbrush. Over-the-counter keratolytic or antiseborrheic shampoos containing zinc, salicylic acid, or tar may be used safely. Antifungal shampoos, such as ketoconazole and ciclopirox, are used if M. furfur is suspected. Low-potency TCS (used twice daily for up to 2 weeks) and calcineurin inhibitors can reduce inflammation and help control pruritus. Tea tree oil is a naturopathic alternative used by many, but lacks supporting studies. See chapter 5 for more information about seborrheic dermatitis in adults.

Secondary bacterial infection is most common in the diaper or intertriginous areas. If oozing occurs, a culture should be obtained and antimicrobials prescribed as needed. Children who scratch or pick off waxy plaques from their scalp are also at increased risk for bacterial infection.

Prognosis and Complications

It usually spontaneously resolves by 8 to 12 months of age. In adolescents and adults, the condition may wax and wane.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Seborrheic dermatitis has no cure. Reassure parents that infantile cradle cap will self-resolve. In older children and adolescents, seborrheic dermatitis has a more chronic course. Daily use of medicated shampoos and antipruritic agents can control symptoms.

DIAPER DERMATITIS

Diaper dermatitis, also called napkin dermatitis or diaper rash, is one of the most common skin conditions of childhood, affecting about 25% of children under 2 years old. “Diaper dermatitis” describes a number of different clinical disorders characterized by acute inflammation in the diaper area. In this section, chafing dermatitis (the most common), irritant dermatitis, and diaper candidiasis are discussed.

Pathophysiology

Inflammation develops when the integrity of the epidermal barrier is compromised by excessive moisture, heat, or irritation. The warm, moist environment of diapers can exacerbate skin irritation.

Chafing dermatitis presents in areas with the most friction (thighs, genitalia, buttocks, and abdomen). Irritant dermatitis results from direct skin contact with urine, stool, or chemicals (soap, detergent, creams). Candida albicans lives in the lower intestine of infants and is usually the causative organism in diaper candidiasis.

Clinical Presentation

Chafing dermatitis presents with mild erythema and fine scale and is due to friction or rubbing from the diaper. Leg openings or waist are commonly affected. Irritant contact dermatitis causes bright red erythema, fine scale, and skin breakdown or superficial erosions on the convex surfaces of the buttocks, vulva, lower abdomen, proximal thighs, and perineum. Diaper candidiasis appears as bright red plaques with white scale at the border located on the buttocks, lower abdomen, and inner thighs. The hallmark features are satellite bright pink-red papules and pustules. Also, examine the oral mucosa to screen for oral thrush.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Diaper dermatitis |

• Seborrheic dermatitis

• Psoriasis

• Intertrigo

• Folliculitis

• Impetigo

• Scabies

• Nutritional deficiency (e.g., acrodermatitis enteropathica)

• Contact dermatitis

• Atopic dermatitis

• Granuloma gluteale infantum

• Langerhans cell histiocytosis

• Epidermolysis bullosa

• Tinea cruris

• Streptococcal perianal cellulitis

Diagnostics

First, differentiate between the types of diaper dermatitis above, then rule out yeast and bacterial infections. If C. albicans is present, microscopic KOH examination will show budding yeasts with pseudohyphae. See Skills Section for how to do a KOH test. Bacterial culture and sensitivity may be helpful. Fungal infection is rare in infants.

Management

Treatment depends on the underlying cause. For chafing dermatitis, reduce the friction by loosening the securing tabs, buying a larger-size diaper, or using barrier creams (reduce frictions). Primary management for irritant dermatitis is to keep the area as clean and dry as possible. Skin will improve with frequent diaper changes; nonirritating, fragrance-free wipes; chemical-free disposable diapers or cloth diapers; exposure to air whenever possible; and liberal use of barrier creams (petrolatum, zinc). In the absence of candidiasis, conservative use of low-potency (nonfluorinated) TCS can be used cautiously for up to 2 weeks, sooner if the dermatitis resolves. Hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment and desonide 0.05% ointment are safe and effective choices.

Diaper candidiasis can be treated with topical antiyeast/fungal creams (nystatin, clotrimazole, ketoconazole). It should be noted, there are combination antifungal/corticosteroid products available, which are commonly used. Using a combination product means that even after the acute inflammation has been calmed, additional treatment with the TCS is necessary if the parent is going to continue to treat the yeast infection. Nystatin/triamcinolone (mid-potency TCS) is available as Mycolog II and is FDA approved for children >2 years old, but should not be used under occlusion (diapers or plastic pants). Clotrimazole/betamethasone dipropionate, available as Lotrisone, contains a high-potency TCS and has been prescribed by some clinicians for diaper dermatitis. It should be noted that it is FDA approved for children 17 years and older for treatment of tinea for no longer than 2 weeks. It should NOT to be used under occlusion. The manufacturer reports that use in children under 17 years for diaper dermatitis has reported adrenal suppression approaching 30%.

The authors suggest use of separate agents to allow the clinician and caregiver to modify the treatment without requiring the administration of both drugs (mild TCS and antifungal) for diaper dermatitis. Oral fluconazole is used for severe cases.

Prognosis and Complications

Once the cause of diaper dermatitis is determined, treatment and management can be administered, and clearance should be completed within days to weeks. Any diaper dermatitis present for more than 3 days is at high risk for developing a secondary candidiasis. Chafing dermatitis and diaper candidiasis are both prone to recurrences. Provide anticipatory guidance about prevention (see Management section).

Patient Education and Follow-up

Prevention is the focus of patient education for all diaper dermatoses. Close follow-up is not needed, as parents should notice improvement a few days after starting treatment. If improvement is not rapid, and in severe or complicated cases, more frequent monitoring may be indicated with phone calls or in-office check-ups, especially if oral medications are required. If treated with TCS, the clinician must educate that caregiver about the administration, risk, benefits, and side effects of therapy.

THRUSH

Infants contract thrush (oral candidiasis) during delivery, nursing from contaminated nipples, contact with contaminated hands, or from improper sterilization of bottles and nipples. Oral thrush in children and adolescents can occur secondary to corticosteroid inhalers used for asthma.

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis of thrush due to C. albicans is the same as for diaper candidiasis.

Clinical Presentation

Thrush appears as white or gray pseudomembranous or velvety patches and plaques on red mucosa that bleeds easily. It affects the tongue, hard and soft palates, buccal mucosa, and gingivae. It can be painful or asymptomatic.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Thrush |

• Aphthous stomatitis

• Candidiasis

• Herpes simplex virus

• Cytomegalovirus

• Blastomycosis

• Esophagitis

• Pharyngitis

• Enteroviral infection

• Human immunodeficiency virus infection

• Histiocytosis

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is often based on clinical findings. To confirm the presence of yeast, gently rub a cotton applicator or tongue depressor on the area to remove some of the plaques and perform a KOH test.

Management

The most common treatment for infants is 2 mL of nystatin 100,000 units per mL, deposited on the inside of each cheek with a dropper, four times a day for 1 to 2 weeks. For infants, the parents should massage the suspension on the mucosa. Mothers who are breastfeeding should also apply the solution to their nipples four times a day. Administer medication between meals to allow for longer contact time. Medicated troches or suppositories used in the tip/slit of a pacifier or bottle are not recommended as it has not been evaluated in controlled studies, and there is a risk for aspiration.

Oral antifungal medications such as fluconazole (Diflucan) should be used if there is a risk for widespread disease. Older children can use nystatin or clotrimazole oral tablets or troches. If corticosteroid inhalers are used for asthma, ensure that the child has good technique with administration, good oral hygiene, and rinse with water after using inhaler.

Special Considerations

Recurrence. Examine for maternal vaginal candidiasis or contaminated nipples or pacifiers. Most treatment failures are due to improper medication application, not resistance, but Candida species are becoming resistant to itraconazole.

Immunosupression. Thrush in immunocompromised children can be severe and may require oral treatment. Candidal esophagitis is a common complication, which can cause dysphagia, respiratory distress, and anorexia.

Prognosis and Complications

Most cases are uncomplicated and clear in 1 to 2 weeks.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Follow-up should be at least 2 weeks after treatment is initiated, to evaluate response to therapy and ensure complete resolution.

APLASIA CUTIS CONGENITA

Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) refers to the absence of epidermis, dermis, and sometimes, subcutaneous tissue, and is present at birth. Most cases are sporadic, but familial cases have been reported. ACC can occur in association with epidermal nevi, premature rupture of membranes, limb abnormalities, epidermolysis bullosa, malformation syndromes, and infections.

Pathophysiology

ACC represents an interruption in intrauterine skin development, but the etiology is not known. Genetic factors, trauma, vascular compromise, intrauterine infections, and teratogens have been suggested, most notably the thyroid medication methimazole (MMI). Parents often assume it is due to the use of forceps during delivery—scratching the scalp and leaving a scar. However, the defect occurs during gestation, as an absence of the skin, and sometimes, subcutaneous tissue.

Clinical Presentation

At birth, ACC can present as an ulcer, superficial erosion, atrophic plaque, or a well-formed scar (Figure 6-6). Lesions that occur early in gestation have time to heal into a scar that will be present at birth. Lesions that occur later in gestation appear as ulceration at birth. Most are 1 to 2 cm in diameter; larger lesions are more likely to extend to deeper structures.

FIG. 6-6. Aplasia cutis congenita. Note that these lesions can be quite subtle.

If a membrane is present, it is called membranous aplasia cutis. Seventy percent of cases occur as a single lesion on the scalp, but it can occur anywhere on the body. Scalp lesions are usually located near the hair whorl at the vertex. The hair collar sign is when ACC is surrounded by a ring of long, dark hair. This is a marker for ACC and can indicate deeper involvement.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Aplasia cutis congenita |

• Birth trauma (e.g., from forceps)

• Nevus sebaceous

Diagnostics

ACC is diagnosed clinically.

Management

Most lesions do not require treatment, but depends on the size, location, and depth of the lesion. Small ACC lesions are managed like any other localized wound. The area should be kept clean and moist with petrolatum, Aquaphor, or silver sulfadiazine ointments that promote healing and prevent further tissue damage. Antibiotics should be used only for culture-confirmed secondary bacterial infections. Infants with full-thickness lesions may require imaging and surgical management.

Prognosis and Complications

Most small lesions heal into a smooth, subtle scar with alopecia within a few weeks or months. Lesions over 4 cm in diameter have the potential for hemmorhage, venous thrombosis, and meningitis. These patients should have CT scan or MRI imaging.

Referral and Consultation

For large and obvious lesions, consult plastic surgery for reconstruction and to prevent complications.

Patient Education and Follow-up

While lesions are healing, follow-up should be regular to monitor progress and screen for secondary infection. Once healing is complete, follow-up is as needed.

NEONATAL LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) is an autoimmune disease that occurs in infants whose mothers have systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); or a tendency for SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, or mixed connective tissue disease. This occurs in less than 2% of births to women with autoimmune diseases.

Pathophysiology

NLE occurs when autoimmune antibodies are passively transferred to the neonate. Only about half of these mothers have a previously diagnosed connective tissue disease. When cardiac manifestations like heart block occurs, it usually develops in utero.

Clinical Presentation

Almost one quarter of infants with NLE have systemic symptoms at birth. Congenital heart block is most common. NLE can also affect the liver, spleen, and lymphatic and hematologic systems.

About half of patients display cutaneous symptoms at some point, including discoid lesions, scaly atrophic plaques, and telangiectasias. Facial erythema is common, especially around the periorbital areas (raccoon eyes). Cutaneous signs may be present at birth, and typically resolve without sequelae within weeks to months (Figures 6-7 and 6-8).

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is based on cutaneous findings, systemic symptoms, and laboratory studies. Further workup includes thorough history and physical examination, CBC with platelets, liver function tests, antinuclear antibody (ANA), urinalysis, and serum complements C3 and C4. If bradycardia or a heart murmur is detected, electrocardiography and echocardiography should be performed. A skin biopsy should be performed, which will show histological features of lupus erythematosus.

FIG. 6-7. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Note the marked facial and periorbital erythema “raccoon eyes.”

FIG. 6-8. Neonatal lupus erythematosus, trunk.

Management

Treatment with low- to mid-potency TCS or topical calcineurin inhibitors can improve erythema, but will not reduce permanent skin changes. Treatment should address any associated systemic disease and complications.

Prognosis and Complications

Skin lesions usually fade by age 6 to 12 months of age, as maternal antibodies wane, but can last longer. One quarter of patients have permanent telangiectasia, hyper- or hypopigmentation, atrophic scars, and/or alopecia.

Special Considerations

Pregnancy. Mothers with one child with NLE have a 22% risk of having another child with NLE.

Referral and Consultation

If neonatal lupus is suspected, consult a dermatologist and a cardiologist.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Reassure parents that patients do not have a higher risk of developing SLE or other autoimmune disorders. These patients should have regular well-child visits with a pediatrician and any other specialties needed to manage other complications.

VASCULAR DISORDERS OF INFANCY

Vascular lesions can be classified into two categories: tumors and malformations. Although both can be present at birth, their pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and evolution during the first few months of life are different. Understanding the progression of various vascular lesions can aid in an accurate diagnosis. Vascular lesions may be associated with or be an indication of systemic disease or genetic syndromes. In this chapter, specific vascular tumors and malformations will be discussed, but tumor and malformation syndromes will not be extensively covered.

VASCULAR TUMORS

Vascular tumors are benign vascular growths that include infantile hemangiomas and pyogenic granulomas. They also include tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, which will not be discussed in this chapter.

INFANTILE HEMANGIOMA

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) or hemangiomas of infancy are the most common benign soft tissue tumor of childhood. They occur in 4 to 10% of full-term infants. IHs are more common in girls than in boys (3 to 5:1) and premature infants. Most are not present at birth, but develop in the first 4 weeks of life, and are often first noticed by the parents.

Pathophysiology

IHs can be categorized as superficial, deep, or mixed, and are described by phases. The proliferation phase occurs within the first 8 weeks of life, much earlier than previously thought, and is characterized by rapid growth. The plateau phase follows for up to 6 months and usually has no growth of the lesion. Then the involutional phase follows where there is dramatic color change from bright red to dull red, purple, or gray. The center of the hemangioma begins to involute or flatten. Lesions become smaller, softer, and less warm. Involution is completed by age 10 years in 90% of cases.

Clinical Presentation

Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red, flat or raised papules, plaques, or nodules. Deep hemangiomas appear as subcutaneous nodules with an overlying blue discoloration and may have telangiectasias or a prominent venous network. Mixed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree