Pathology of Breast Disorders

Baljit Singh

Pathology of the breast encompasses a wide variety of disorders, including benign, premalignant, and malignant diseases, as well as disorders of uncertain malignant potential. A variety of infections and systemic diseases may affect the breast. This chapter presents a review of the pathology of breast diseases with an emphasis on common diseases, biomarkers, and emerging concepts that impact clinical practice.

The functional unit of the breast is the terminal ductal lobular unit. This is composed of small acini, which drain into a terminal duct. The terminal duct is the first tributary of the ductal system of the breast, which functions to extrude milk from the nipple. The entire lobular and ductal structure of the breast is lined by two layers of cells, the inner epithelial layer and the outer myoepithelial layer. “Breast cancer” typically refers to breast carcinoma, which arises by preferential growth of the inner epithelial layer. A useful corollary of this paradigm is that the demonstration of the absence of myoepithelial cells by immunohistochemistry can be used by the pathologist to determine the malignant potential of a lesion.

Benign Disorders

Fibrocystic change is the pathologic condition that correlates with “lumpy, bumpy” breasts. This term is applied to a plethora of benign changes in the breast, which are best categorized based on the subsequent risk of development of breast carcinoma. Dupont and Page (1,2) reviewed benign breast biopsies from 3,000 women and used well-defined criteria to categorize them into three groups: nonproliferative lesions, proliferative lesions without atypia, and atypical hyperplasia. This clinically relevant classification has been independently corroborated and sanctioned by a consensus conference of the College of American Pathologists (3,4).

Nonproliferative Lesions

This is the most common category of breast disorders and includes cysts, papillary apocrine change, mild hyperplasia of the usual type, and epithelial related calcifications. Women with these lesions do not incur a higher risk of development of breast carcinoma than that of women who had no breast biopsy (relative risk, 0.89).

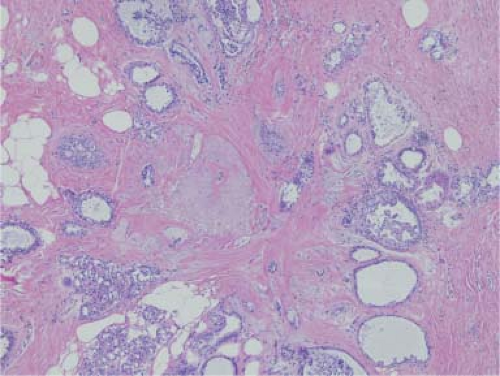

In the early 20th century Joseph Bloodgood described blue cysts in the breast (blue domed cysts of Bloodgood) (5). Haagensen noted that cysts may form a palpable mass, and thus he termed them gross cysts (6). However, most cysts are small and can be visualized only on microscopic examination (Fig. 5.1). Not uncommonly, cystic change is accompanied by apocrine change of the lining epithelial cells. Oncocytic change is ubiquitous throughout the body, and these cells have characteristic abundant, pink, granular cytoplasm. Apocrine cells in the ductal system are often columnar and proliferate with a papillary architecture, with or without fibrovascular cores. Architectural or cellular atypia in apocrine cells does not increase the risk of cancer development. Mild hyperplasia of the usual type falls into this category and is defined as epithelial proliferation in a duct that is less than four cells thick and does not cross the lumen.

Proliferative Lesions Without Atypia

Women with these lesions have a slight risk of development of breast carcinoma, 1.5 to 2 times that of the general population. This category includes moderate or florid hyperplasia of the usual type, sclerosing adenosis, small-duct papillomas, and fibroadenomas (1,7).

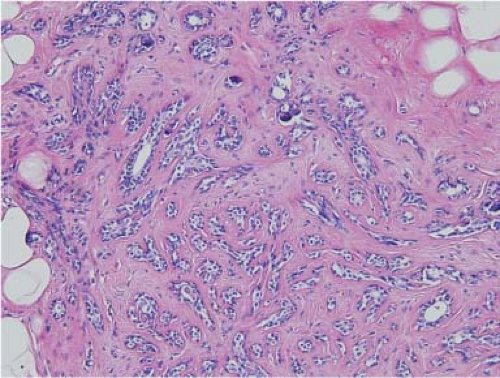

Sclerosing adenosis is the most common lesion and refers to expanded lobular units with a proliferation of both acini and intervening stroma. Microcalcifications are often seen in association with sclerosing adenosis and frequently correspond to “benign calcifications” seen on mammography (Fig. 5.2). Rarely, a clinically palpable mass may be formed by a large number of lobules with cellular sclerosing adenosis and has been referred to as adenosis tumor. Usual ductal hyperplasia, moderate or florid, includes epithelial proliferation in ducts that are more than four cells thick and distend the ducts. Characteristically, they have a slitlike fenestrated pattern (Fig. 5.3). Solid and papillary patterns may also be seen. The cells may overlap, show slight variability in shape and size, and have a swirling or streaming pattern. Small duct papillomas arise in the peripheral duct system and tend to multiple. Microscopically, they are composed of fibrovascular papillae covered with the two cell types of the ductal system, the inner epithelial and the outer myoepithelial cells.

Atypical Hyperplasias

Atypical hyperplasias confer a risk of development of breast carcinoma that is 3.5 to 5 times that of the reference population. This category includes both atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia (1,2).

These lesions are difficult diagnostic problems, with variable interobserver agreement (8,9,10). Their morphologic features are midway between those of usual hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ. Page et al. defined criteria for atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) that are widely used and include nuclear monomorphism, regular cell placement, and round (not fenestrated) spaces in part of the duct (Fig. 5.4). Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) (11) refers to proliferation of lobular cells with distention of acini in no more than half of a lobule and may include pagetoid spread into adjacent ducts (12).

Earlier studies showed that atypical hyperplasias do not have a linear progression to carcinoma and increase the risk of development of breast carcinoma in both breasts (2,13). They have, therefore, been considered to be general risk factors.

A recent retrospective analysis found that the breast diagnosed with ALH is three times more likely to develop invasive carcinoma than the contralateral breast (14). These data suggest that ALH may lie somewhere between linear progression and generalized risk.

A recent retrospective analysis found that the breast diagnosed with ALH is three times more likely to develop invasive carcinoma than the contralateral breast (14). These data suggest that ALH may lie somewhere between linear progression and generalized risk.

Figure 5.1. Fibrocystic change, nonproliferative type. Two cysts are filled with inspissated secretions. Dense fibrosis is seen in the background with normal and atrophic lobules. |

Columnar cell hyperplasia (CCH) with or without atypia is a newly recognized morphologic entity. CCH without atypia is one of many hyperplastic lesions that slightly increase the relative risk of development of breast carcinoma and are grouped under fibrocystic change, proliferative type (15). CCH are frequently associated with microcalcifications and may have mild, moderate, or marked atypia. Severe atypia typically has a micropapillary architecture and may be indistinguishable from ductal carcinoma in situ. CCH has been noted to be associated with ALH, lobular carcinoma in situ, and tubular carcinoma (16). As with other atypical proliferative lesions, there is a high level of interobserver variability among pathologists in diagnosing CCH with atypia (17). Flat epithelial atypia is also a newly recognized morphologic entity (16). There is no prospective or retrospective evidence from clinical trials regarding the prognostic value of either CCH or flat epithelial atypia.

Figure 5.2. Sclerosing adenosis. An enlarged lobule has numerous acini in a sclerotic, dense stroma with focal microcalcifications. |

Figure 5.3. Usual ductal hyperplasia. The ducts are full of overlapping cells with indistinct borders, forming a sievelike pattern. |

A diagnosis of an atypical lesion of any type as rendered on a core biopsy is an indication for a surgical biopsy. Atypical lesions are diagnosed in 4.3% to 6.7% patients who undergo a core biopsy for a mammographically detected lesion, and the subsequent surgical biopsy reveals intraductal carcinoma in 12.5% to 36% and invasive carcinoma in 0% to 14% of patients (18,19,20,21). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening has been recommended for women at high risk for development of breast carcinoma. MRI-guided biopsies are increasingly utilized for premenopausal women with dense breasts (22). There is paucity of good radiologic/pathologic correlative studies for “indefinite” lesions seen on MRI.

Figure 5.5. Radial scar. The central zone is sclerotic with a few compressed ducts. Dilated ducts are seen at the periphery, some of which show usual ductal hyperplasia. |

Atypical lesions of the breast are a diagnostic challenge for the surgical pathologist, and there is considerable interobserver variation among pathologists in interpreting these lesions. The Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation published a white paper on breast pathology (23) that recommends that the accuracy of diagnosis of breast lesions can be enhanced by specialty training, second opinions, and integration of pathologists into clinical care teams.

Radial Scars and Complex Sclerosing Lesions

Radial scars are typically small areas of scarring (<1 cm) surrounded by glandular elements. Their stellate morphology mimics a classic scirrhous carcinoma for both the mammographer and the pathologist. Typically, they are seen only on microscopy, which reveals an area of intense sclerosis in the center, surrounded by dilated ducts, sclerosing adenosis, and apocrine metaplasia (Fig. 5.5). Glands caught up in the central scirrhous zone may mimic invasive carcinoma on high magnification. The overall architecture of the lesion is critical in avoiding this pitfall, especially on frozen section. Numerous sclerotic lesions do not have the classic morphology of a radial scar but show varying degrees of sclerosis and ductal hyperplasia. These lesions are commonly referred to as complex sclerosing lesions.

In a carefully performed case–control study, it was shown that women with biopsy-proven radial scars are at an increased risk for breast cancer. Women with proliferative lesions with atypia associated with radial scar had a relative risk of breast cancer of 3.0 (24).

Benign Neoplasms

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenomas typically present as painless, mobile, rubbery masses. They are usually solitary but are occasionally multiple (25). They are most often present in the upper outer quadrant and are slightly more common in the left breast. Fibroadenomas are more common in Black women.

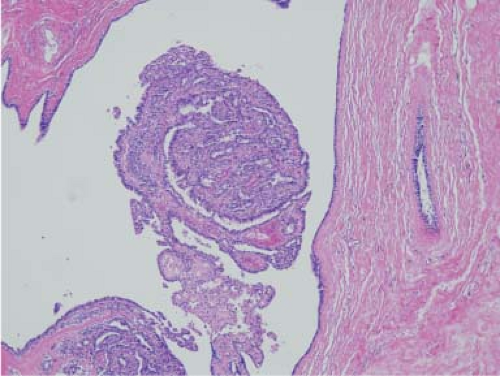

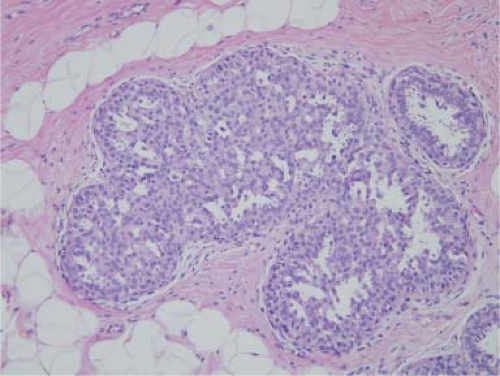

Figure 5.6. Fibroadenoma. The tumor is circumscribed and covered by a pseudo-capsule. It is composed of numerous ducts in a background of cellular stroma. |

On gross examination, fibroadenomas are well-circumscribed masses that bulge on cut section. The cut surface may be gelatinous, and slitlike spaces can be discerned on occasion. On microscopic examination, fibroadenomas are biphasic and have epithelial and stromal components (Fig. 5.6). The epithelial component is usually formed by ducts lined by inner ductal and outer myoepithelial cells. The stroma consists of fibrous tissue with variable cellularity. Occasionally, the epithelial component is insignificant and the stromal component is hypocellular and densely sclerotic. This variant, hyalinized fibroadenoma, is invariably associated with coarse microcalcifications, which may be worrisome to the mammographer.

Juvenile fibroadenoma is a variant seen in young girls, and these tumors show both epithelial and stromal hypercellularity (26). They may be multiple, grow rapidly, and cause venous dilation in the overlying skin. Tubular adenoma is a subtype that has an abundance of small tubules on microscopic examination and is also common in young women (27). Complex fibroadenomas contain cysts larger than 3 mm, sclerosing adenosis, epithelial calcifications, or papillary apocrine change. One study showed a higher risk of breast cancer (28) in patients with such lesions.

Lactational adenomas are seen during pregnancy and in the postpartum period and may represent lactational changes superimposed on an underlying tubular adenoma or fibroadenoma. They present as a well-circumscribed mass, which on microscopy shows glands and ducts with secretory changes. Infarction, pain, and tenderness may complicate fibroadenomas during pregnancy.

Solitary (Large-Duct) Intraductal Papilloma

These tumors typically arise in a large duct in the subareolar region and present with unilateral hemorrhagic discharge. One nested case–control study showed that papillomas with areas of ADH within them have a risk of breast carcinoma at

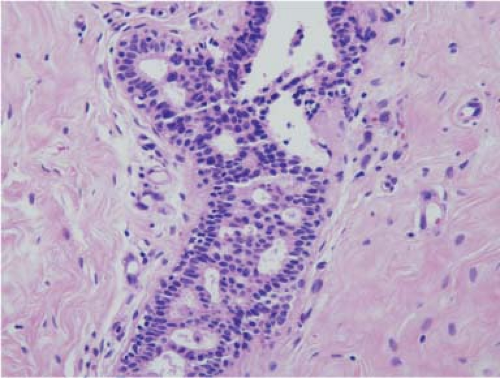

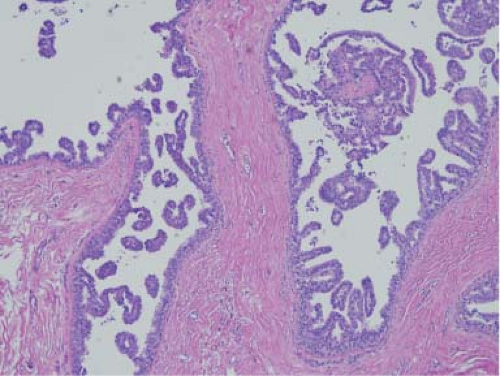

that site, which is similar to the risk associated with ADH in the adjacent breast (30). On careful dissection papillomas appear as pearly, small, white nodules. Microscopically, they distend a duct and are composed of a stalk with branching thick fibrovascular cores lined by myoepithelial and ductal cells (Fig. 5.7). The proliferation of both cell types is an indicator of benignity. Complex growth patterns can make the distinction between a papilloma and papillary carcinoma challenging for the pathologist. The entire lesion should be submitted for microscopic examination to rule out any area of invasion. Papillomas typically do not show significant pleomorphism, mitotic activity, and necrosis (31,32).

that site, which is similar to the risk associated with ADH in the adjacent breast (30). On careful dissection papillomas appear as pearly, small, white nodules. Microscopically, they distend a duct and are composed of a stalk with branching thick fibrovascular cores lined by myoepithelial and ductal cells (Fig. 5.7). The proliferation of both cell types is an indicator of benignity. Complex growth patterns can make the distinction between a papilloma and papillary carcinoma challenging for the pathologist. The entire lesion should be submitted for microscopic examination to rule out any area of invasion. Papillomas typically do not show significant pleomorphism, mitotic activity, and necrosis (31,32).

Phyllodes Tumor

This entity encompasses tumors that run the gamut from benign to malignant but mostly fall into the category of tumors of uncertain malignant potential (borderline). Conventionally, phyllodes tumors have been referred to as cystosarcoma phyllodes, an unfortunate term connoting malignant behavior.

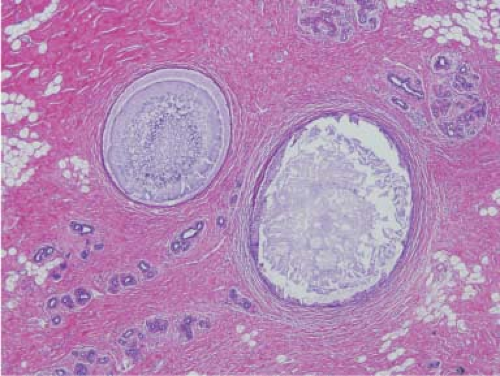

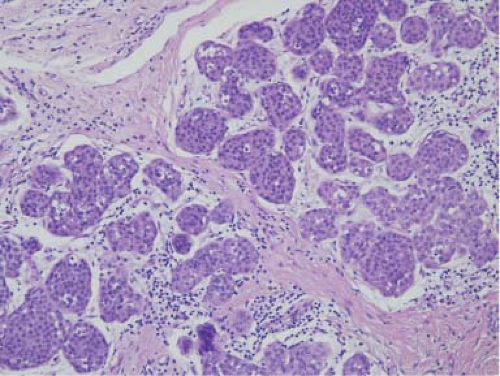

On gross examination, phyllodes tumors can be of any size and appear fleshy, with sharp delineation from surrounding breast tissue. Microscopically, they have characteristic hypercellular stroma around the ductal elements, which are typically compressed (intracanalicular pattern) (Fig. 5.8). A high mitotic count, nuclear pleomorphism, and stromal overgrowth are the main criteria used to assess biological behavior (33,34). As with all stromal tumors, ample sampling is necessary because the sarcomatous component may be small and limited to a small portion of the tumor. Phyllodes tumors tend to have local recurrences and should be widely excised (35,36). Most tumors that metastasize show overt sarcomatous areas.

Nipple Adenoma

Adenomas of the nipple present as ill-defined masses in the nipple region. Microscopically, they are composed of glandlike spaces associated with proliferation of ductal epithelium. The latter may show a pseudo-invasion pattern and extension into the nipple, which may clinically mimic Paget’s disease. The presence of both myoepithelial and epithelial layers in this lesion is an indicator of benignity. These lesions should be examined in their entirety because they have been reported in rare cases to be associated with carcinoma (37,38).

Miscellaneous Lesions

Microglandular adenosis is an uncommon lesion that mimics tubular carcinoma. It is usually seen in women older than 40 years and may present as an ill-defined mass. Microscopically, it is composed of small glands interspersed in the stroma and fat. The glands are lined by a single layer of epithelial cells but are surrounded by a basement membrane. Numerous authors have shown a tenuous concurrence of this lesion with carcinoma (39,40,41,42). Lipoma is an ill-defined entity in the breast. Clinically apparent masses sometimes yield only fat without any glandular elements on excision and are diagnosed as lipoma. Fibromatosis is a locally invasive neoplastic condition that afflicts numerous sites in the body and is best recognized as desmoid tumor of the abdominal wall. Microscopically, it consists of proliferation of benign-appearing spindle-shaped cells, which invade breast parenchyma. Wide excision is curative (43,44,45,46). Rosen described the entity mucocele-like lesion, which consists of extravasated mucin from mucinous cysts and may present as a mass (47). Pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia of the mammary stroma may clinically present as a mass. The proliferating fibroblasts line slitlike spaces and mimic vascular proliferation (48,49,50). A variety of benign stromal tumors may be seen in the breast, including leiomyoma, neurofibroma, myofibroblastoma, and chondrolipoma.

Inflammatory Conditions

Fat Necrosis

Fat necrosis seen in the breast is most commonly iatrogenic. However, on occasion it can mimic breast carcinoma both clinically and on mammography. In the early phase, microscopic examination shows a cavity lined by histiocytes with a

foamy cytoplasm with a smattering of chronic inflammatory cells. With time, foreign-body giant cells appear and the lesion becomes sclerotic and may develop coarse microcalcifications, which can be recognized as such by an expert mammographer.

foamy cytoplasm with a smattering of chronic inflammatory cells. With time, foreign-body giant cells appear and the lesion becomes sclerotic and may develop coarse microcalcifications, which can be recognized as such by an expert mammographer.

Mammary Duct Ectasia

This disease typically presents as an ill-defined mass in the areolar lesion in a perimenopausal woman. The ducts in this region are dilated and associated with chronic inflammation. Occasionally, abundant plasma cells are seen (plasma cell mastitis), and this condition has been described as a separate entity (51) but probably represents a variant. It can mimic breast carcinoma (52,53,54,55).

Granulomatous Mastitis

This is a descriptive term that encompasses different etiologies. Mammary tuberculosis is rare. Sarcoidosis can affect the breasts on occasion and should be diagnosed only when all infectious agents have been excluded (56). Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis may be associated with microabscesses and responds to corticosteroid therapy (51,57).

Lobular Carcinoma in Situ

Foote and Stewart (58) introduced the concept of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) in 1941. They observed that LCIS is a rare, multicentric entity that cannot be identified clinically or on gross examination; the invasive carcinoma that might develop might be either ductal or lobular. Their observations have stood the test of time. LCIS has been reported to have a variable incidence ranging from 0.5 to 3.6 (59,60,61,62), depending on the cohort studied and diagnostic criteria used. LCIS is more common in younger, premenopausal women, and the mean age of diagnosis is 44 to 46 years. African American women have a tenfold lower incidence of LCIS than White women in the United States (56,63,64). In the mammography era the incidence of LCIS has apparently increased (65). Numerous studies have shown that LCIS is commonly bilateral and multicentric (present in more than one quadrant). The incidence of bilaterality varies from 23% to 69% (66,67), and multicentricity varies from 60% to 85% (68,69,70).

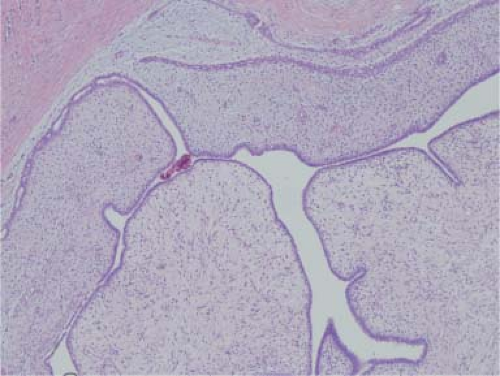

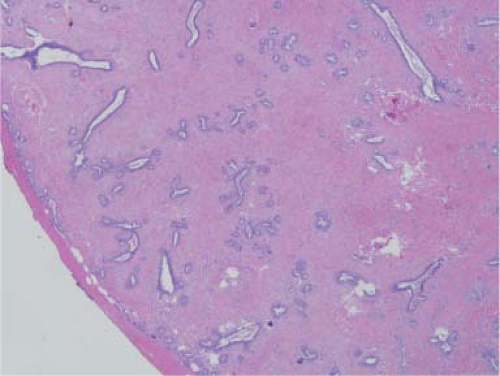

LCIS is typically an incidental finding in a breast biopsy done for a mammographically detectable lesion, which may be calcifications in adjacent sclerosing adenosis or other proliferative lesions. Calcifications are rarely associated with LCIS. A typical case of LCIS shows proliferation of monotonous small cells in lobules, which have a bubbly cytoplasm and bland nuclei and distend acini in lobules and track along ducts (pagetoid spread) (Fig. 5.9). These cells may have mucinous (signet ring), clear, myoid, or mosaic features. Occasionally, the cells have highly atypical nuclei, and this variant is referred to as pleomorphic LCIS.

The distinction between ALH and LCIS is quantitative. The monotonous cell proliferation should distend and obliterate the lumen in 50% to 75% of acini of a lobule (61,71). Estrogen receptor (ER) is typically overexpressed in cells of LCIS and Her2/neu is not (72). E-cadherin is a useful marker to distinguish lobular and ductal proliferations, as it is preferentially expressed in the latter (73).

Figure 5.9. Lobular carcinoma in situ. Lobules are distended with monomorphic cells with moderate amount of cytoplasm and low-grade nuclei. |

Most women with LCIS do not develop invasive carcinoma on follow-up. However, LCIS confers a relative risk of development of subsequent carcinoma that varies from 6.9 to 12 (56,60,61,62), which may occur in either breast with equal frequency. These carcinomas are mostly invasive ductal carcinomas. Invasive lobular carcinomas occur in 25% to 37% of patients, which is significantly higher than the incidence of 5% to 10% seen in the general population. No morphologic or molecular characteristics can accurately predict which cases of LCIS will go on to develop invasive carcinoma.

These data suggest that that LCIS is best considered to be a risk factor rather than a precursor of invasive carcinoma. Surgical management of LCIS thus does not aim for negative margins, and radiation therapy has no role in management of LCIS. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) prevention trial showed a significant reduction of subsequent carcinoma with tamoxifen.

Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) comprises lesions in which the neoplastic growth of ductal cells is restricted to within the ductal system. DCIS is considered to be a direct precursor of invasive carcinoma. The data to support this paradigm come from small series of patients whose biopsies were misclassified as benign and were found to have DCIS on retrospective review. The incidence of carcinoma in these patients varied from 11% to 53% (74,75,76). Unlike LCIS, all the invasive carcinomas occurred in the ipsilateral breast in the vicinity of the biopsy site.

Mammographic abnormalities, which commonly show microcalcifications, are the most common presentation of DCIS. DCIS may present as a mass with or without nipple discharge. The incidence of DCIS increased 587% from 1973 to 1992 (77). Screening mammography alone cannot account for this dramatic increase.

Figure 5.10. Micropapillary ductal carcinoma in situ. The ducts are lined by small papillae without discernible fibrovascular cores. |

The neoplastic cells can show varying degrees of differentiation and architectural patterns. They can involve lobules, and this is referred to as lobular cancerization. The cells may form solid, papillary, micropapillary, clinging, and cribriform patterns. Micropapillary DCIS is more likely to be more multicentric (80%) than other types of DCIS (36%) (78) (Fig. 5.10). Comedo pattern refers to central necrosis in the ducts that are lined by poorly differentiated cells. Comedo DCIS is invariably associated with calcifications (Fig. 5.11). Comedo necrosis was the only factor found to correlate with ipsilateral recurrence in a multivariate analysis of nine histologic features of DCIS in retrospective pathologic analysis of patients accrued to NSABP B-17 (79). A consensus conference in 1997 suggested that nuclear grade (low, intermediate, and high), necrosis, cell polarization, and architectural patterns be mentioned in all diagnosis of DCIS (80). There can be significant interobserver discordance among pathologists in classifying DCIS. The lesions at the interface of ADH and low-grade DCIS can be problematic for the most experienced pathologist (8,9,81). The distinction between LCIS and DCIS can usually be made without difficulty. E-cadherin staining is a useful adjunct in difficult cases since it is almost always shows no staining in lobular proliferations (73).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree